Csr Site, Pyrmont Archaeological Investigations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Office Investment Review & Outlook 2019

Australian Office Investment Review & Outlook 2019 Table of contents 03 Executive summary 04 What were the key observations from 2018? 09 What industry sectors will contribute to growth in 2019? 16 Should we be concerned by the supply-side of the equation? 18 How do we assess the relative value of office markets? 24 Will AUD volatility have an impact on investment flows? 27 Is it time to allocate more resources to exploring markets outside of Sydney and Melbourne? 28 Outlook 30 Summary of Major Transactions 2 Office Investment Review & Outlook 2019 Executive Summary Transaction volumes surpass AUD 19 billion for New development activity is pre-commitment the first time on record: The Australian office sector led: Developers have remained risk averse and recorded AUD 19.53 billion of transaction volumes in 2018 typically looked to secure healthy levels of pre- – the highest figure on record. Volumes were supported commitment prior to starting construction. We by the acquisition of Investa Office Fund (IOF) by Oxford have observed an inverse relationship between Properties for AUD3.4 billion. However, the number of office prime grade vacancy and the development transactions was lower than previous years with pipeline. Office markets with low prime grade the top 10 office transactions representing 43.9% of total vacancy are experiencing higher levels of new volume in 2018. development activity. AUD volatility could stimulate investment activity: The relative Offshore divestment hit a record value of the AUD is influenced by high: Offshore capital sources interest rate differentials, GDP growth remained active participants in the and commodity prices. -

Renewal Ultimo Historical Walking Tour

historical walking tours RENEWAL ULTIMO Historical Walking Tour Front Cover Image: Tram passing Sydney Technical College, 1950s (Photograph: City of Sydney Archives) ultimo Then the landscape was remade by sandstone ntil 1850, Ultimo was semi-rural, quarrying on Ultimo’s western edge and by the with cornfields and cow paddocks. construction of a railway and goods yard on its Members of the Gadigal people still eastern shoreline. The suburb became crowded harvested cockles on its foreshores. with factories, woolstores and workers’ housing. Today it has a new identity as a cultural precinct as industrial sites are adapted for entertainment and education. This tour of Ultimo starts in greyness and ends in the technicolour of Darling Harbour. Sydney’s PLEASE ALLOW 1½ – 2 hours for this tour. WHY ULTIMO? history Begin the walk at The story of Ultimo began with a court case is all around us. Railway Square outside the and a joke. In the 1800s, Governor King was Our walking tours will lead you Marcus Clark Building (1). engaged in a power struggle with officers on a journey of discovery from of the NSW Corps. Surgeon John Harris early Aboriginal life through to of the Corps supported him, and became contemporary Sydney. so unpopular with his colleagues that he was court-martialled in 1803. But Harris escaped conviction because the charge stated he had committed an offence on the “19th ultimo” (last month) instead of “19th instant” (this month). When Governor King rewarded Harris with land grants, he Clover Moore MP celebrated the technicality by calling his Lord Mayor of Sydney estate Ultimo. -

Shelter NSW Submission Rapid Assessment Framework NSW Department of Planning, Industry, and Environment Date 12.2.2021

Shelter NSW Submission Rapid Assessment Framework NSW Department of Planning, Industry, and Environment Date 12.2.2021 Introduction Shelter NSW appreciates the opportunity to comment on the Department of Planning, Industry, and Environment (DPIE), proposed Rapid Assessment Framework. Shelter NSW supports the Government’s objective to provide clear guidance and increase the efficiency and transparency of the assessment process for a major project while also improving community engagement standards. Shelter NSW’s submission responds to the growing demand for the NSW planning system to deliver on its promise of a more equitable city, and this includes the capacity to deliver affordable rental housing in one of the most expensive housing markets in the world. An objective of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (d) is to promote the delivery and maintenance of affordable housing. However, there is a growing acknowledgment that a key barrier in meeting this objective and addressing both housing need and affordability is the expanding complexities of the planning system, various legislation, policy and public authorities. Shelter NSW has provided feedback on the proposed changes and associated documentation in the Rapid Assessment Framework package. This feedback is informed by Shelter NSW's involvement with community organisations who are engaged with several ‘State Significant Development’ (SSD) housing projects and associated community engagement initiatives which do not support the delivery of an equitable and sustainable city. We hope these insights help the Government in meeting its overall goals, while also addressing some of the current system failures. About Shelter NSW Shelter NSW has operated since 1975 as the NSW State peak housing policy and advocacy body. -

Charter Hall Property Portfolio

CHARTER HALL PROPERTY PORTFOLIO Charter Hall Property Portfolio Period ending 30 June 2019 2 Market Street, Sydney NSW 10 Shelley Street, Sydney NSW CHARTER HALL 1 PROPERTY PORTFOLIO $30.4 b Funds Under Management 844 3.4% Number of Weighted Average Properties Rent Review (WARR) 97.9% 8.2 years Occupancy Weighted Average Lease Expiry (WALE) Richlands Distribution Facility, QLD CHARTER HALL 2 PROPERTY PORTFOLIO CONTENTS CHARTER HALL GROUP 3 OUR FUNDS, PARTNERSHIPS & MANDATES 5 OFFICE 7 CHARTER HALL PRIME OFFICE FUND (CPOF) 8 CHARTER HALL OFFICE TRUST (CHOT) 24 OFFICE MANDATES AND PARTNERSHIPS 32 CHARTER HALL DIRECT OFFICE FUND (DOF) 36 CHARTER HALL DIRECT PFA FUND (PFA) 47 INDUSTRIAL 57 CHARTER HALL PRIME INDUSTRIAL FUND (CPIF) 58 CORE LOGISTICS PARTNERSHIP (CLP) 95 CHARTER HALL DIRECT INDUSTRIAL FUND NO.2 (DIF2) 98 CHARTER HALL DIRECT INDUSTRIAL FUND NO.3 (DIF3) 106 CHARTER HALL DIRECT INDUSTRIAL FUND NO.4 (DIF4) 114 CHARTER HALL DIRECT CDC TRUST (CHIF12) 121 RETAIL 123 CHARTER HALL PRIME RETAIL FUND (CPRF) 124 CHARTER HALL RETAIL REIT (CQR) 127 RETAIL PARTNERSHIP NO.1 (RP1) 137 RETAIL PARTNERSHIP NO.2 (RP2) 141 RETAIL PARTNERSHIP NO.6 (RP6) 143 LONG WALE HARDWARE PARTNERSHIP (LWHP) 145 LONG WALE INVESTMENT PARTNERSHIP (LWIP) 150 LONG WALE INVESTMENT PARTNERSHIP NO.2 (LWIP2) 152 CHARTER HALL DIRECT BW TRUST (CHIF11) 153 CHARTER HALL DIRECT AUTOMOTIVE TRUST (DAT) 154 CHARTER HALL DIRECT AUTOMOTIVE TRUST NO.2 (DAT2) 157 DIVERSIFIED 161 CHARTER HALL LONG WALE REIT (CLW) 162 DVP 184 DIVERSIFIED CONSUMER STAPLES FUND (DCSF) 185 SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE 194 CHARTER HALL EDUCATION TRUST (CQE) 195 CHARTER HALL CIB FUND (CIB) 215 INDEX 216 FURTHER INFORMATION 228 Gateway Plaza, VIC CHARTER HALL 3 PROPERTY PORTFOLIO Charter Hall Group (ASX:CHC) With over 28 years’ experience in property investment and funds management, we’re one of Australia’s leading fully integrated property groups. -

Space For: Going Places

Space for: going places CITY WEST OFFICE PARK 33–35 SAUNDERS STREET, PYRMONT, NSW OVERVIEW 2 Premium office space in a prime location Position your business in premium office space, among high profile brands in the thriving Pyrmont precinct. Centrally located on Saunders Street, City West Office Park offers the unique combination of high quality, modern office space within close proximity to a range of entertainment and dining options. The estate is the location of choice for high profile brands, including Network Ten, Nova 96.9, 9Radio, UNICEF, National Film and Restaurant Brands Australia. Pyrmont has emerged as a thriving media and technology hub, attracting leading brands, including Google, OMD Worldwide, BMF Australia and IBM. VIEW FROM ABOVE 3 Sydney CBD North Sydney Barangaroo King Street Wharf The Star City West Office Park Western Distributor FISH MARKET LIGHT RAIL STATION Sydney Fish Market Anzac Bridge LOCATION 4 Superior connectivity City West Office Park offers convenient access to the CBD, Sydney Airport and local amenities, with major bus routes, Sydney Light Rail and Sydney ferry terminals within walking distance of the estate. Vehicles accessing the estate will benefit from close proximity to City West Link and the Western Distributor, offering convenient Light Rail, buses and connections to greater Sydney. motorways offer superior connections to the CBD and greater Sydney CENTR ALLY CONNECTED 200M 900M 14.7KM to light rail to City West to Sydney 100M 900M Link 2.6KM Airport to bus stop to ferry terminal to Sydney CBD -

State Heritage I Inventory Project D

I I I I I I I :1 PYRMONT POINT PRECINCT I Archaeological and Heritage Assessment ,I Report prepared for I Property Services Group I Godden Mackay Pty Ltd I Howard Tanner and Associates Pty Ltd I I March 1993 I I I 'I ;1 ·1 :1. , ~ :1 I I I I CONTENTS Page I 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1.1 Context of the Report 1 1.2 Objectives 1 I 1.3 Historical Context 1 1.4 Heritage Resources 2 1.5 Statutory Controls 3 I 1.6 Management Recommendations 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION 5 2.1 Background 5 I 2.2 Study Area 5 2.3 Author Identification 6 2.4 Methodology 6 I 2.5 Umitations 6 3.0 HISTORIC CONTEXT 8 I 3.1 The Development of Pyrmont 8 3.2 1788 - 1840 Early Settlement and the Macarthurs 9 3.3 Subdivision, Settlement and Community (1840 - 1910) 11 3.4 Reconstructing the Point: Port Wharfage (1910 -1970) 13 I 3.5 Derelict, Demolished, Developed (1970 - 1992) 14 I 4.0 LANDSCAPE 31 5.0 BUILT ENVIRONMENT 33 I 6.0 ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES 36 6.1 Preamble 36 6.2 The Value ofArchaeological Material 37 I 6.3 Existing Information 37 6.4 Potential Historical Archaeological Sites 38 6.5 Significance 39 I 6.6 Procedures 40 I I I I I I I I I I CONTENTS Page 7.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANT ITEMS 42 I 7.1 Recording Methodology 42 7.2 Basis for Assessment of Significance 42 7.3 Contribution to the Overall Significance of Pyrmont 45 I 7.4 Results 46 7.4.1 Heritage Items Recommendedfor the Retention, Conservation and Inclusion on the Heritage Schedule I ofREP 26 46 7.4.2 Items Which Contribute to the Overall Signifcance ofPyrmont 47 7.5 Review of Specific Items, with Reference to the -

Pyrmont Peninsula Place Strategy

Pyrmont Peninsula Place Strategy December 2020 Acknowledgement of Country The Department of Planning, Industry and Environment acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land and pays respect to Elders past, present and future. We recognise Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ unique cultural and spiritual relationships to place and their rich contribution to society. Aboriginal people take a holistic view of land, water and culture and see them as one, not in isolation to each other. The Pyrmont Peninsula Place Strategy is based on the premise upheld by Aboriginal people that if we care for Country, it will care for us. Published by NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment dpie.nsw.gov.au Pyrmont Peninsula Place Strategy December 2020 ISBN: 978-1-76058-406-1 Cover image sources: Destination NSW and Shutterstock Artwork (left) by Nikita Ridgeway © State of New South Wales through Department of Planning, Industry and Environment 2020. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment as the owner. However, you must obtain permission if you wish to charge others for access to the publication (other than at cost); include the publication in advertising or a product for sale; modify the publication; or republish the publication on a website. You may freely link to the publication on a departmental website. Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing (December 2020) and may not be accurate, current or complete. -

Ecology of Pyrmont Peninsula 1788 - 2008

Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Sydney, 2010. Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula iii Executive summary City Council’s ‘Sustainable Sydney 2030’ initiative ‘is a vision for the sustainable development of the City for the next 20 years and beyond’. It has a largely anthropocentric basis, that is ‘viewing and interpreting everything in terms of human experience and values’(Macquarie Dictionary, 2005). The perspective taken here is that Council’s initiative, vital though it is, should be underpinned by an ecocentric ethic to succeed. This latter was defined by Aldo Leopold in 1949, 60 years ago, as ‘a philosophy that recognizes[sic] that the ecosphere, rather than any individual organism[notably humans] is the source and support of all life and as such advises a holistic and eco-centric approach to government, industry, and individual’(http://dictionary.babylon.com). Some relevant considerations are set out in Part 1: General Introduction. In this report, Pyrmont peninsula - that is the communities of Pyrmont and Ultimo – is considered as a microcosm of the City of Sydney, indeed of urban areas globally. An extensive series of early views of the peninsula are presented to help the reader better visualise this place as it was early in European settlement (Part 2: Early views of Pyrmont peninsula). The physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula has been transformed since European settlement, and Part 3: Physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula describes the geology, soils, topography, shoreline and drainage as they would most likely have appeared to the first Europeans to set foot there. -

Dexus (ASX: DXS) ASX Release

Dexus (ASX: DXS) ASX release 25 October 2017 Bank of America Merrill Lynch Australian Real Estate Conference presentation Dexus today provides the attached presentation to be used as a basis of discussion with institutional investors at the 2017 Bank of America Merrill Lynch Australian Real Estate Conference. The conference is being held at the offices of Bank of America Merrill Lynch in Sydney. For further information please contact: Investor Relations Media Relations Melanie Bourke Louise Murray +61 2 9017 1168 +61 2 9017 1446 +61 405 130 824 +61 403 260 754 [email protected] [email protected] About Dexus Dexus is one of Australia’s leading real estate groups, proudly managing a high quality Australian property portfolio valued at $24.9 billion. We believe that the strength and quality of our relationships will always be central to our success, and are deeply committed to working with our customers to provide spaces that engage and inspire. We invest only in Australia, and directly own $12.2 billion of office and industrial properties. We manage a further $12.7 billion of office, retail, industrial and healthcare properties for third party clients. The group’s $4.3 billion development pipeline provides the opportunity to grow both portfolios and enhance future returns. With 1.8 million square metres of office workspace across 54 properties, we are Australia’s preferred office partner. Dexus is a Top 50 entity by market capitalisation listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (trading code: DXS) and is supported by 28,000 investors from 20 countries. With more than 30 years of expertise in property investment, development and asset management, we have a proven track record in capital and risk management, providing service excellence to tenants and delivering superior risk-adjusted returns for investors. -

Contested Territorialities in Millers and Dawes Points, Sydney, Australia

Contested Territorialities in Millers and Dawes Points, Sydney, Australia Helen Karathomas A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences Faculty of Science University of New South Wales September 2015 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES - Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname: Karathomas First name: Helen Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: Biological Earth and Environmental Sciences Faculty: Science Title: Contested Territorialities in Millers and Dawes Points, Sydney, Australia. Abstract (350 words maximum): Millers and Dawes Points are two harbour side, inner city suburbs of Sydney that have been subject to contests over space. Because of Millers and Dawes Points’ histories, the area contains some of Sydney’s oldest residential housing. More recently, certain areas within Millers and Dawes Points have experienced residential and commercial gentrification. This thesis extends existing gentrification studies through a middle range framework, which includes the concepts of ‘territoriality’, ‘sense of place’ and ‘placelessness’. This theoretical framework increases our understandings of the changes occurring in local areas. Nestled within the suburbs of Millers and Dawes Points are pockets of social housing occupied by residents who are dubbed the ‘traditional community’. The traditional community live cheek by jowl with some of the area’s wealthier residents who reside in the suburbs’ ‘privatopias’ (McKenzie 1994, 9). These wealthier residents are gentrifiers who I have labelled as the ‘new community’ in this thesis. This thesis identifies how these communities have developed distinct senses of and attachments to place that have been constructed and manifested within Millers and Dawes Points’ complex and contested terrain. -

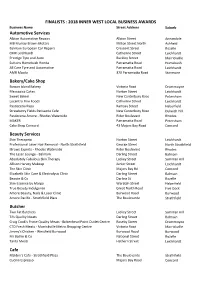

2018 05 Finalists

FINALISTS : 2018 INNER WEST LOCAL BUSINESS AWARDS Business Name Street Address Suburb Automotive Services Albion Automotive Repairs Albion Street Annandale MB Murray Brown Motors Milton Street North Ashfield Balmain European Car Repairs Crescent Street Rozelle CMR Leichhardt Catherine Street Leichhardt Prestige Tyre and Auto Buckley Street Marrickville Suttons Homebush Honda Parramatta Road Homebush All Care Tyre and Automotive Parramatta Road Leichhardt AMR Mazda 370 Parramatta Road Stanmore Bakery/Cake Shop Bowan Island Bakery Victoria Road Drummoyne Mezzapica Cakes Norton Street Leichhardt Sweet Belem New Canterbury Road Petersham Locantro Fine Foods Catherine Street Leichhardt Pasticceria Papa Ramsay Street Haberfield Strawberry Fields Patisserie Cafe New Canterbury Road Dulwich Hill Pasticceria Amore - Rhodes Waterside Rider Boulevard Rhodes MAKER Parramatta Road Petersham Cake Shop Concord 43 Majors Bay Road Concord Beauty Services Skin Therapeia Norton Street Leichhardt Professional Laser Hair Removal - North Strathfield George Street North Strathfield IBrows Experts - Rhodes Waterside Rider Boulevard Rhodes The Laser Lounge - Balmain Darling Street Balmain Absolutely Fabulous Skin Therapy Lackey Street Summer Hill Allison Harvey Makeup Junior Street Leichhardt The Skin Clinic Majors Bay Rd Concord Elizabeth Skin Care & Electrolysis Clinic Darling Street Balmain Beaute & Co Darling St Rozelle Skin Essence by Margo Waratah Street Haberfield True Beauty Indulgence Great North Road Five Dock Amore Beauty, Nails & Laser Clinic Burwood -

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION 732 HARRIS STREET ULTIMO 2007 CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION 732 HARRIS STREET ULTIMO 2007 A Project Funded by Spurbest pty Ltd CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 01 1. 1 The Project.............................................................................................................. 02 1.2 The Pre-Settlement Environment ........................................................................... 02 1.3 On the Fringe of Settlement. ................................................................................... 02 1.4 Ultimo Estate ........................................................................................................... 03 1.5 Samuel Blackman's House ..................................................................................... 03 1.6 The Lamb Inn .......................................................................................................... 03 1.7 859-869 George Street ........................................................................................... 04 1.8 857 George Street .................................................................................................. 04 1.9 851-855 George Street ........................................................................................... 04 1.10 849 George Street .................................................................................................