Lymphangiosarcoma of Dogs: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon

16_DeSchepper_Tumors_and 15.09.2005 13:27 Uhr Seite 263 Chapter Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon Contents 42]. There are two major classification schemes for vas- cular tumors. That of Enzinger et al. [12] relies on 16.1 Introduction . 263 pathological criteria and includes clinical and radiolog- 16.2 Definition and Classification . 264 ical features when appropriate. On the other hand, the 16.2.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 264 classification of Mulliken and Glowacki [42] is based on 16.2.1.1 Classification of Mulliken . 264 endothelial growth characteristics and distinguishes 16.2.1.2 Classification of Enzinger . 264 16.2.1.3 WHO Classification . 265 hemangiomas from vascular malformations. The latter 16.2.2 Vascular Tumors of Borderline classification shows good correlation with the clinical or Intermediate Malignancy . 265 picture and imaging findings. 16.2.3 Malignant Vascular Tumors . 265 Hemangiomas are characterized by a phase of prolif- 16.2.4 Glomus Tumor . 266 eration and a stationary period, followed by involution. 16.2.5 Hemangiopericytoma . 266 Vascular malformations are no real tumors and can be 16.3 Incidence and Clinical Behavior . 266 divided into low- or high-flow lesions [65]. 16.3.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 266 Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions are usually 16.3.2 Angiomatous Syndromes . 267 easily diagnosed and present no significant diagnostic 16.3.3 Hemangioendothelioma . 267 problems. On the other hand, hemangiomas or vascular 16.3.4 Angiosarcomas . 268 16.3.5 Glomus Tumor . 268 malformations that arise in deep soft tissue must be dif- 16.3.6 Hemangiopericytoma . -

Lymphangioma Circumscriptum of the Vulva- a Case Series Dermatology Section

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2021/47435.14553 Case Series Lymphangioma Circumscriptum of the Vulva- A Case Series Dermatology Section RASHMI S MAHAJAN1, YOGESH S MARFATIA2, ATMAKALYANI R SHAH3, KISHAN R NINAMA4 ABSTRACT Vulval dermatoses pose a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the dermatologists. Lymphangioma Circumscriptum (LC) is a form of lymphangioma affecting the skin and subcutaneous tissues that is characterised by benign dilation of lymphatic channels. This uncommon condition is known to occur over the chest, mouth, axilla, tongue, and rarely in the vulva. In this series, authors present three cases of LC of vulva in women between the age group of 45 to 60 years with late-onset fluid-filled lesions over the vulva. The first case had history of hysterectomy prior to onset of lesions, the second case had a spontaneous onset of lesions while the third was a suspected case of pelvic tuberculosis with secondary lymphangioma. Keywords: Lymphangiectasia, Vulvar, Vulval epithelium INTRODUCTION Disorders of vulval epithelium are a confusing spectrum of disorders. They are broadly classified as-1) Inflammatory, 2) Ulcerative and Bullous, 3) Infections, 4) Benign tumours and 5) Malignancies. It is essential to know the exact aetiology to plan successful therapy. LC is a benign lymphatic malformation characterised by dilation of lymphatic vessels in the skin and subcutaneous tissue with lesions erupting locally as isolated or grouped translucid, thin-walled vesicles filled with a clear liquid [1]. These pathological lymphatic malformations have no communication with the normal lymphatics [2]. The precise cause of LC is not established. It could be congenital or acquired as a result of damage to the lymphatic vessels secondary to various aetiologies. -

Two Cases of Lymphangioma Circumscriptum Successfully Treated

Letters to the Editor REFERENCES 8. Kato N. Vertically growing ectopic nail. J Cutan Pathol 1992;19:445‑7. 9. Nath AK, Udayashankar C. Congenital onychogryphosis: Leaning Tower nail. Dermatol Online J 2011;17:9. 1. Barad P, Fernandes J, Ghodge R, Shukla P. Vertically growing Nail. 10. Zaias N. The Nail in Health and Disease. 2nd ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton Indian Dermatol Online J 2015;6;288‑9. and Lange; 1990. p. 164. 2. Fleckman P. Structure and function of the nail unit. In: 3rd, editors. Nails: 11. Ohata C, Shirabe H, Takagi K. Onychogryphosis with granulation tissue Therapy, Diagnosis and Surgery :Saunders; 2005. p. 13‑26. of proximal nail fold. Skin Res 1996;38:626‑9. 3. Kligman AM. Why do nails grow out instead of up? Arch Dermatol 1961;84:313‑5. 4. Kikuchi I, Ogata K, Idemori M. Vertically growing ectopic nail: Nature’s Access this article online experiment on nail growth direction. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10:114‑6. Quick Response Code: 5. Baran R. Nail growth direction revisited. Why do nails grow out instead of up? J Am Acad Dermatol 1981;4:78‑84. 6. Grover C, Bansal S, Nanda S, Reddy BS, Kumar V. En bloc excision of Website: www.idoj.in proximal nail fold for treatment of chronic paronychia. Dermatol Surg 2006;32:393‑9. 7. Hashimoto K. Ultrastructure of the human toenail. I. Proximal nail matrix. J Invest Dermatol 1971;56:235‑46. Letter to the Editor twice per year. Nothing in particular was noted in her family Two cases of lymphangioma history or her laboratory tests. -

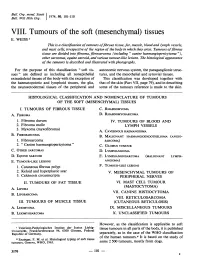

Mesenchymal) Tissues E

Bull. Org. mond. San 11974,) 50, 101-110 Bull. Wid Hith Org.j VIII. Tumours of the soft (mesenchymal) tissues E. WEISS 1 This is a classification oftumours offibrous tissue, fat, muscle, blood and lymph vessels, and mast cells, irrespective of the region of the body in which they arise. Tumours offibrous tissue are divided into fibroma, fibrosarcoma (including " canine haemangiopericytoma "), other sarcomas, equine sarcoid, and various tumour-like lesions. The histological appearance of the tamours is described and illustrated with photographs. For the purpose of this classification " soft tis- autonomic nervous system, the paraganglionic struc- sues" are defined as including all nonepithelial tures, and the mesothelial and synovial tissues. extraskeletal tissues of the body with the exception of This classification was developed together with the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, the glia, that of the skin (Part VII, page 79), and in describing the neuroectodermal tissues of the peripheral and some of the tumours reference is made to the skin. HISTOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF TUMOURS OF THE SOFT (MESENCHYMAL) TISSUES I. TUMOURS OF FIBROUS TISSUE C. RHABDOMYOMA A. FIBROMA D. RHABDOMYOSARCOMA 1. Fibroma durum IV. TUMOURS OF BLOOD AND 2. Fibroma molle LYMPH VESSELS 3. Myxoma (myxofibroma) A. CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA B. FIBROSARCOMA B. MALIGNANT HAEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA (ANGIO- 1. Fibrosarcoma SARCOMA) 2. " Canine haemangiopericytoma" C. GLOMUS TUMOUR C. OTHER SARCOMAS D. LYMPHANGIOMA D. EQUINE SARCOID E. LYMPHANGIOSARCOMA (MALIGNANT LYMPH- E. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS ANGIOMA) 1. Cutaneous fibrous polyp F. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS 2. Keloid and hyperplastic scar V. MESENCHYMAL TUMOURS OF 3. Calcinosis circumscripta PERIPHERAL NERVES II. TUMOURS OF FAT TISSUE VI. -

Kaposi's Sarcoma: a Review of 136 Rhodesian African Cases John A

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.43.502.513 on 1 August 1967. Downloaded from Postgrad. med. J. (August 1967) 43, 513-519. Kaposi's sarcoma: A review of 136 Rhodesian African cases JoHN A. GORDON M.B., Ch.B.(Cape Town), F.R.C.S.(Edin.) Surgeon, Harari Central Hospital, Salisbury, Rhodesia; Cancer Association Fellow of the Cancer Association of Rhodesia to the Westminster Hospital, London KAPosi's syndrome was originally described by University of Chicago cancer registry from 1946 Moricz Kaposi, Professor of Dermatology in the to 1960 showed eight cases of Kaposi's sarcoma in University of Vienna in 1872. The condition was 13,700 malignancies. thought to be rare and virtually confined to Central European Jews, although later it was also Age described in Mediterranean peoples. There was The original and subsequent 'European' des- even evidence that amongst the Jews the con- cription stressed that the patient would be in the dition was confined to the Ashkenazic sect sixth or seventh decades. However, Oettle (1962) (Rothman, 1962). Early reports were often based found that the African patients were between 35 on small series of cases, rarely numbering more and 44 years. At Harari Hospital some difficulty than a dozen. has been experienced in establishing ages but none Since the original masterly description of the in the series was over 50 years and this seems to copyright. disease (Kaposi, 1872) there has been much con- correspond closely with Oettle's figures though at fused discussion on all aspects of the tumour. least one patient was 24 years of age. -

8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87409-0 - Modern Soft Tissue Pathology: Tumors and Non-Neoplastic Conditions Edited by Markku Miettinen Index More information Index abdominal ependymoma, 744 mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, 631 adult fibrosarcoma (AF), 364–365, 1026 abdominal extrauterine smooth muscle ovarian adenocarcinoma, 72, 79 adult granulosa cell tumor, 523–524 tumors, 79 pancreatic adenocarcinoma, 846 clinical features, 523 abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic pulmonary adenocarcinoma, 51 genetics, 524 tumors, 297–298 renal adenocarcinoma, 67 pathology, 523–524 abdominal leiomyoma, 467, 477 serous cystadenocarcinoma, 631 adult rhabdomyoma, 548–549 abdominal leiomyosarcoma. See urinary bladder/urogenital tract clinical features, 548 gastrointestinal stromal tumor adenocarcinoma, 72, 401 differential diagnosis, 549 (GIST) uterine adenocarcinomas, 72 genetics, 549 abdominal perivascular epithelioid cell tumors adenofibroma, 523 pathology, 548–549 (PEComas), 542 adenoid cystic carcinoma, 1035 aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM), 514–518 abdominal wall desmoids, 244 adenomatoid tumor, 811–813 clinical features, 514–516 acquired elastotic hemangioma, 598 adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, 143 differential diagnosis, 518 acquired tufted angioma, 590 adenosarcoma (mullerian¨ adenosarcoma), 523 genetics, 518 acral arteriovenous tumor, 583 adipocytic lesions (cytology), 1017–1022 pathology, 516 acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma atypical lipomatous tumor/well- aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma, (AMIFS), 365–370, 1026 differentiated -

Lymphangioma Circumscriptum: Clinicopathological Spectrum of 29

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Lymphangioma Circumscriptum: Clinicopathological Spectrum of 29 Cases Saira Fatima, Nasir Uddin, Romana Idrees, Khurram Minhas, Zubair Ahmad, Rashida Ahmad, Naila Kayani and Muhammad Arif ABSTRACT Objective: To describe the clinicopathological spectrum of Lymphangioma Circumscriptum (LC). Study Design: Observational case series. Place and Duration of Study: Department of Pathology and Microbiology, AKUH, Karachi, from 2002 to 2012. Methodology: All reported cases of LC were retrieved from medical record. Clinical and pathological features were noted. Frequency percentages were determined. Results: There were 29 cases of LC predominantly males (62%). The mean age was 27.17 ± 15.5 years. The commonest sites was anal/perianal region (24%) followed by extremities (17%) and tongue, (14%). Vulval LC was seen in 3 patients. Two cases were described on scrotum. The lesions were most commonly suspected as viral warts, mole or polyp (in anal region). Vesicles with erosions and bleeding and localized growth were the usual clinical presentations. Four of the patients presented with swelling since birth. All were treated with surgical excision. Microscopic examination revealed acanthotic squamous epithelium with papillomatosis. The subepithelial region had collections of lymphatic channels composed of ectatic dilated vessels with serum and inflammatory cells in their lumina. The lymphatic channels were seen in deeper layers along with lymphocytic aggregates. Conclusion: Lymphangioma circumscriptum is a malformation of abnormal lymphatic channels with feeding cisterns in subcutaneous tissue. It is a benign lesion usually occurring in anal/perianal region and confused with warts. Surgical excision is preferred mode of treatment. Key Words: Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum. Warts. Lymphatic malformation. INTRODUCTION The term lymphangioma circumscriptum was first coined Lymphangiomas are malformations of lymphatic by Morris et al. -

A Clinicopathological and Immunohistochemical Study of Lymphatic Differentiation in 49 Angiosarcomas

Histopathology 2010, 56, 364–371. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03484.x Can lymphangiosarcoma be resurrected? A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of lymphatic differentiation in 49 angiosarcomas Cohra C Mankey, Jonathan B McHugh, Dafydd G Thomas & David R Lucas Department of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA Date of submission 18 November 2008 Accepted for publication 12 June 2009 Mankey C C, McHugh J B, Thomas D G & Lucas D R (2010) Histopathology 56, 364–371 Can lymphangiosarcoma be resurrected? A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of lymphatic differentiation in 49 angiosarcomas Aims: The term lymphangiosarcoma has largely been as hobnail and kaposiform morphologies were more abandoned in the current classification of endothelial often positive with these markers, including a statistical neoplasms. Recently, a number of lymphatic-associated association between D2-40 and hobnailing. Ten antibodies have been developed for immunohistochem- tumours had features suggestive of lymphatic differen- istry, which frequently stain angiosarcomas, implying tiation, namely well-differentiated histology, interanas- lymphatic or mixed lymphatic and blood vascular tomosing channels devoid of red cells, prominent differentiation is common. The aim was to investigate hobnailing, lymphoid aggregates, and multi-antigen further lymphatic antigen expression, and to explore expression of D2-40 (100%), Prox-1 (100%) and the relation of immunohistochemistry to morphological VEGFR-3 (60%), which might be deserving of the and clinical findings. appellation lymphangiosarcoma. Nine were cutaneous Methods and results: Forty-nine angiosarcomas in scalp ⁄ facial tumours in elderly patients and one arose tissue microarrays were analysed with D2-40 and within chronic lymphoedema. antibodies to Prox-1 and vascular endothelial growth Conclusions: Lymphatic differentiation is common in factor receptor (VEGFR)-3. -

Malignant Vascular Tumors&Mdash

Modern Pathology (2014) 27, S30–S38 S30 & 2014 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/14 $32.00 Malignant vascular tumors—an update Cristina Antonescu Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA Although benign hemangiomas are among the most common diagnoses amid connective tissue tumors, sarcomas showing endothelial differentiation (ie, angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma) represent under 1% of all sarcoma diagnoses, and thus it is likely that fewer than 500 people in the United States are affected each year. Differential diagnosis of malignant vascular tumors can be often quite challenging, either at the low end of the spectrum, distinguishing an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma from an epithelioid hemangioma, or at the high-grade end of the spectrum, between an angiosarcoma and a malignant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Within this differential diagnosis both clinico-radiological features (ie, size and multifocality) and immunohistochemical markers (ie, expression of endothelial markers) are often similar and cannot distinguish between benign and malignant vascular lesions. Molecular ancillary tests have long been needed for a more objective diagnosis and classification of malignant vascular tumors, particularly within the epithelioid phenotype. As significant advances have been recently made in understanding the genetic signatures of vascular tumors, this review will take the opportunity to provide a detailed update on these findings. Specifically, this article will focus on -

Purpuric Macule of the Right Axilla

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Purpuric Macule of the Right Axilla Andrew L.J. Dunn, MD; Brett H. Keeling, MD; Justin P. Bandino, MD; Dirk M. Elston, MD; John S. Metcalf, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 67-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the medial aspect of the right axilla of 2 weeks’ duration. The patientcopy had a history of cancer of the right breast treated with a mastectomy and adjuvant radiation. She denied pain, bleeding, pruritus, or rapid growth, as well as any changes in medicationnot or recent trauma. Physical examina- tion revealed a 5-mm purpuric macule of the right axilla. A punch biopsy was performed. Amplifica- tion for the C-MYC gene was negative by fluores- Docence in situ hybridization. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. atypical vascular lesion H&E, original magnification ×100 (Ki-67 immunostain, original magnifi- cation ×100 [inset]). b. hobnail hemangioma (targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma) c. Kaposi sarcoma CUTIS d. lymphangioma circumscriptum (superficial lymphangioma) e. radiation-induced angiosarcoma PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 29 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS Dr. Dunn is from the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Services, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock. -

What Is Your Diagnosis?

PHOTO QUIZ What Is Your Diagnosis? Patients reported leakage of straw-colored fluid when the lesions were traumatized. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 310 FOR DISCUSSION Dirk M. Elston, MD, Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. LTC Richard Vinson, MC, USA, Department of Dermatology, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas. The authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as representing those of the Army Medical Department or the Department of Defense. The authors were full-time federal employees at the time this work was completed. It is in the public domain. VOLUME 76, NOVEMBER 2005 301 Photo Quiz Discussion The Diagnosis: Lymphangioma Circumscriptum (Benign Lymphangiectasia) esions of lymphangioma circumscriptum and may be misdiagnosed as condylomata acu- look like clusters of clear fluid-filled vesicles minatum.7,8 Vulvar lesions may occur following resembling frog eggs. The lesions may surgery or radiation therapy, or they may arise L 1 9 occur in a zosteriform distribution. Verrucous spontaneously. The most common patient com- hyperplasia of the epidermis and associated tis- plaint relates to the clear fluid oozing from the sue edema may be noted. Some vesicles contain lesions. Pain and cellulitis also may occur as blood in addition to lymph and Kim et al2 complications.10 Squamous cell carcinoma has reported solitary nodular angiokeratoma in a been reported in long-standing lymphangioma -

Osteopathic Journal Feb 2006 6

Journal of the AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC COLLEGE OF DERMATOLOGY 2005-2006 Officers Journal of the President: Richard A. Miller, DO President-Elect: Bill V. Way, DO American First Vice-President: Jay S. Gottlieb, DO Second Vice-President: Donald K. Tillman, DO Third Vice-President: Marc I. Epstein, DO Osteopathic Secretary-Treasurer: Jere J. Mammino, DO Immediate Past President: Ronald C. Miller, DO College Trustees: David W. Dorton, DO Bradley P. Glick, DO of Dermatology Daniel S. Hurd, DO Jeffrey N. Martin, DO Executive Director: Rebecca Mansfield, MA Editors Jay S. Gottlieb, D.O., F.O.C.O.O. Stanley E. Skopit, D.O., F.A.O.C.D. Associate Editor James Q. Del Rosso, D.O., F.A.O.C.D. Editorial Review Board Ronald Miller, D.O. Eugene Conte, D.O. Evangelos Poulos, M.D. Stephen Purcell, D.O. AOCD • 1501 E. Illinois • Kirksville, MO 63501 Darrel Rigel, M.D. 800-449-2623 • FAX: 660-627-2623 www.aocd.org Robert Schwarze, D.O. Andrew Hanly, M.D. COPYRIGHT AND PERMISSION: written permission must be Michael Scott, D.O. obtained from the Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology for copying or reprinting text of more than half page, Cindy Hoffman, D.O. tables or figures. Permissions are normally granted contingent upon Charles Hughes, D.O. similar permission from the author(s), inclusion of acknowledgement Bill Way, D.O. of the original source, and a payment of $15 per page, table or figure of reproduced material. Permission fees are waived for authors Daniel Hurd, D.O. wishing to reproduce their own articles.