Sargasssum Fact Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

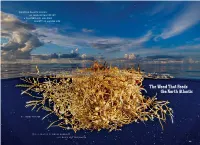

The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic

DRIFTING PLANTS KNOWN AS SARGASSUM SUPPORT A COMPLEX AND AMAZING VARIETY OF MARINE LIFE. The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic BY JAMES PROSEK PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID DOUBILET AND DAVID LIITTSCHWAGER 129 Hatchling sea turtles, like this juvenile log- gerhead, make their way from the sandy beaches where they were born toward mats of sargassum weed, finding food and refuge from predators during their first years of life. PREVIOUS PHOTO A clump of sargassum weed the size of a soccer ball drifts near Bermuda in the slow swirl of the Sargasso Sea, part of the North Atlantic gyre. A weed mass this small may shelter thousands of organisms, from larval fish to seahorses. DAVID DOUBILET (BOTH) 130 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC THE WEED THAT FEEDS THE NORTH ATLANTIC 131 ‘There’s nothing like it in any other ocean,’ says marine biologist Brian Lapointe. ‘There’s nowhere else on our blue planet that supports such diversity in the middle of the ocean—and it’s because of the weed.’ LAPOINTE IS TALKING about a floating seaweed known as sargassum in a region of the Atlantic called the Sargasso Sea. The boundaries of this sea are vague, defined not by landmasses but by five major currents that swirl in a clockwise embrace around Bermuda. Far from any main- land, its waters are nutrient poor and therefore exceptionally clear and stunningly blue. The Sargasso Sea, part of the vast whirlpool known as the North Atlantic gyre, often has been described as an oceanic desert—and it would appear to be, if it weren’t for the floating mats of sargassum. -

Pelagic Sargassum Community Change Over a 40-Year Period: Temporal and Spatial Variability

Mar Biol (2014) 161:2735–2751 DOI 10.1007/s00227-014-2539-y ORIGINAL PAPER Pelagic Sargassum community change over a 40-year period: temporal and spatial variability C. L. Huffard · S. von Thun · A. D. Sherman · K. Sealey · K. L. Smith Jr. Received: 20 May 2014 / Accepted: 3 September 2014 / Published online: 14 September 2014 © The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Pelagic forms of the brown algae (Phaeo- ranging across the Sargasso Sea, Gulf Stream, and south phyceae) Sargassum spp. and their conspicuous rafts are of the subtropical convergence zone. Recent samples also defining characteristics of the Sargasso Sea in the western recorded low coverage by sessile epibionts, both calcifying North Atlantic. Given rising temperatures and acidity in forms and hydroids. The diversity and species composi- the surface ocean, we hypothesized that macrofauna asso- tion of macrofauna communities associated with Sargas- ciated with Sargassum in the Sargasso Sea have changed sum might be inherently unstable. While several biological with respect to species composition, diversity, evenness, and oceanographic factors might have contributed to these and sessile epibiota coverage since studies were con- observations, including a decline in pH, increase in sum- ducted 40 years ago. Sargassum communities were sam- mer temperatures, and changes in the abundance and distri- pled along a transect through the Sargasso Sea in 2011 and bution of Sargassum seaweed in the area, it is not currently 2012 and compared to samples collected in the Sargasso possible to attribute direct causal links. Sea, Gulf Stream, and south of the subtropical conver- gence zone from 1966 to 1975. -

First Report of the Asian Seaweed Sargassum Filicinum Harvey (Fucales) in California, USA

First Report of the Asian Seaweed Sargassum filicinum Harvey (Fucales) in California, USA Kathy Ann Miller1, John M. Engle2, Shinya Uwai3, Hiroshi Kawai3 1University Herbarium, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA 2 Marine Science Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara, California, USA 3 Research Center for Inland Seas, Kobe University, Rokkodai, Kobe 657–8501, Japan correspondence: Kathy Ann Miller e-mail: [email protected] fax: 1-510-643-5390 telephone: 510-387-8305 1 ABSTRACT We report the occurrence of the brown seaweed Sargassum filicinum Harvey in southern California. Sargassum filicinum is native to Japan and Korea. It is monoecious, a trait that increases its chance of establishment. In October 2003, Sargassum filicinum was collected in Long Beach Harbor. In April 2006, we discovered three populations of this species on the leeward west end of Santa Catalina Island. Many of the individuals were large, reproductive and senescent; a few were small, young but precociously reproductive. We compared the sequences of the mitochondrial cox3 gene for 6 individuals from the 3 sites at Catalina with 3 samples from 3 sites in the Seto Inland Sea, Japan region. The 9 sequences (469 bp in length) were identical. Sargassum filicinum may have been introduced through shipping to Long Beach; it may have spread to Catalina via pleasure boats from the mainland. Key words: California, cox3, invasive seaweed, Japan, macroalgae, Sargassum filicinum, Sargassum horneri INTRODUCTION The brown seaweed Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt, originally from northeast Asia, was first reported on the west coast of North America in the early 20th c. (Scagel 1956), reached southern California in 1970 (Setzer & Link 1971) and has become a common component of California intertidal and subtidal communities (Ambrose and Nelson 1982, Deysher and Norton 1982, Wilson 2001, Britton-Simmons 2004). -

Dynamic of the Sargassum Tide Holobiont in the Caribbean Islands

From the Sea to the Land: Dynamic of the Sargassum Tide Holobiont in the Caribbean Islands Pascal Jean Lopez ( [email protected] ) CNRS Délégation Paris B https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9914-4252 Vincent Hervé Max-Planck-Institut for Terrestrial Microbiology Josie Lambourdière Centre National de la Recherche Scientique Malika René-Trouillefou Universite des Antilles et de la Guyane Damien Devault Centre National de la Recherche Scientique Research Keywords: Macroalgae, Methanogenic archaea, Sulfate-reducing bacteria, Epibiont, Microbial communities, Nematodes, Ciliates Posted Date: June 9th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-33861/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/27 Abstract Background Over the last decade, intensity and frequency of Sargassum blooms in the Caribbean Sea and central Atlantic Ocean have dramatically increased, causing growing ecological, social and economic concern throughout the entire Caribbean region. These golden-brown tides form an ecosystem that maintains life for a large number of associated species, and their circulation across the Atlantic Ocean support the displacement and maybe the settlement of various species, especially microorganisms. To comprehensively identify the micro- and meiofauna associated to Sargassum, one hundred samples were collected during the 2018 tide events that were the largest ever recorded. Results We investigated the composition and the existence of specic species in three compartments, namely, Sargassum at tide sites, in the surrounding seawater, and in inland seaweed storage sites. Metabarcoding data revealed shifts between compartments in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities, and large differences for eukaryotes especially bryozoans, nematodes and ciliates. -

<I>Histrio Histrio</I>

A CONTRIBUTION 'ro THE BIOLOGY AND POSTLARVAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE SA.RGASSUM FISH, HISTRIO HISTRIO (LINNAEUS), vVITH A DISCUSSION OF THE SARGilSSUM COMPLEX' JUDITH A. ADAMS The Marine Laboratory, University of Miami ABSTRACT The early development of the Sargassum fish, Histrio histrio (Linnaeus), is described, based upon a collection of 44 larval and juvenile specimens from the Florida Current. Growth, biology, feeding and relationship to the Sargassum complex are discussed. Specimens at various stages of develop- ment are illustrated. INTRODUCTION The fishes of the family Antennariidae have attracted considerable interest because of their curious form, coloration, and behavior. Reef and bank-dwelling antennariids are widely distributed throughout warm, shallow seas in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and the pelagic member of the family, Histrio histrio, occurs in floating weed over a similar area, although wind and current may at times carry these drifters far into temperate waters. Despite, however, the interest and availability of this group, its taxonomy was not clarified until quite recently (Barbour, 1942; Schultz, 1957), and many reports were buri~d in the proliferating synonomy. Histrio histrio alone, though now regarded as belonging to a monotypic genus, has seventeen synonyms as listed by Schultz (1957). Larval stages and eggs of the Antennariidae were unknown to early workers; this led several respected biologists to attribute erroneously the "nests" of flying fish to Histrio. Subsequently, non-fertile egg rafts of solitary Histrio females were observed in aquaria. In 1954 Mosher successfully paired ripe males and females in aquaria at the Lerner Marine Laboratory, Bimini, Bahamas, and recorded the spawning and fertilization of Histrio egg rafts. -

Productivity and Nutrition of Sargassum: a Comparative

PRODUCTIVITY AND NUTRITION OF SARGASSUM: A COMPARATIVE ECOPHYSIOLOGICAL STUDY OF BENTHIC AND PELAGIC SPECIES IN FLORIDA by Alison I. Feibel A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Charles E. Schmidt College of Science In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2016 Copyright 2016 by Alison I. Feibel ii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS The author wishes to express her gratitude to her advisor Dr. Brian Lapointe for his guidance, advice, and mentorship throughout this project. Laura Herren deserves many thanks for making the completion of this project possible. The author is grateful to everyone at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute who contributed time and resources to this project. Lastly, the author wishes to express her love and thanks to her parents and brother for their unwavering support throughout this endeavor. iv ABSTRACT Author: Alison Feibel Title: Productivity and Nutrition of Sargassum: A Comparative Ecophysiological Study of Benthic and Pelagic Species in Florida Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Brian E. Lapointe Degree: Master of Science Year: 2016 Benthic algal species receive elevated nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) availability as anthropogenic activities increase the loading of nutrients into coastal waters. Pelagic species could also be responding to this nutrient enrichment. This study compared the tissue nutrient content and productivity of three benthic and two pelagic species of Sargassum. We hypothesized that the benthic species would have a higher tissue nutrient content and productivity than the pelagic species and the pelagic species would have a higher tissue nutrient content and productivity than historic data. -

Modifications to Gray Triggerfish Catch Levels

3/5/2021 Modifications to Gray Triggerfish Catch Levels Final Framework Action to the Fishery Management Plan for Reef Fish Resources of the Gulf of Mexico Including Environmental Assessment, Regulatory Impact Review, and Regulatory Flexibility Analysis March 2021 This is a publication of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council Pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA20NMF4410011. This page intentionally blank ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT COVER SHEET Name of Action Framework Action to the Fishery Management Plan for Reef Fish Resources in the Gulf of Mexico: Modifications to Gray Triggerfish Catch Levels including Environmental Assessment, Regulatory Impact Review, and Regulatory Flexibility Act Analysis. Responsible Agencies and Contact Persons Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council (Council) 813-348-1630 4107 W. Spruce Street, Suite 200 813-348-1711 (fax) Tampa, Florida 33607 [email protected] Carly Somerset ([email protected]) Gulf Council Website National Marine Fisheries Service (Lead Agency) 727-824-5305 Southeast Regional Office 727-824-5308 (fax) 263 13th Avenue South SERO Website St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 Kelli O’Donnell ([email protected]) Type of Action ( ) Administrative ( ) Legislative ( ) Draft (X) Final This Environmental Assessment is being prepared using the 2020 CEQ NEPA Regulations. The effective date of the 2020 CEQ NEPA Regulations was September 14, 2020, and reviews begun after this date are required to apply the 2020 regulations unless there is a clear and fundamental conflict with an applicable statute. 85 Fed. Reg. at 43372-73 (§§ 1506.13, 1507.3(a)). This Environmental Assessment began on January 28, 2021, and accordingly proceeds under the 2020 regulations. -

Why Does Sargassum Smell So Bad? How Can Hydrogen Sulfide Affect My

Ron DeSantis Mission: Governor To protect, promote & improve the health of all people in Florida through integrated Scott A. Rivkees, MD state, county & community efforts. State Surgeon General Vision: To be the Healthiest State in the Nation SARGASSUM Sargassum is a type of brown seaweed that is washing up on beaches in Florida. As it rots, it gives off a substance called hydrogen sulfide. Hydrogen sulfide has a very unpleasant odor, like rotten eggs. Although the seaweed itself cannot harm your health, tiny sea creatures that live in Sargassum can cause skin rashes and blisters. Learn more about Sargassum—what it is, how it can harm your health, and how to protect yourself and your family from possible health effects. What is Sargassum Does Sargassum cause skin rashes and Sargassum is a brown seaweed that floats in the blisters? ocean and is washing up on Florida beaches in Sargassum does not sting or cause rashes. large amounts. However, tiny organisms that live in Sargassum (like larvae of jellyfish) may irritate skin if they It provides an important habitat for migratory come in contact with it. organisms that have adapted specifically to this floating algae including crab, shrimp, sea turtles, Will hydrogen sulfide from rotting and commercially important fish species such as Sargassum cause cancer or other long- tuna and marlin. term health effects? Hydrogen sulfide is not known to cause cancer Why is Sargassum a concern? in humans. If you are exposed to hydrogen The tiny sea creatures that live in Sargassum sulfide for a long time in an enclosed space with can irritate skin with direct contact. -

SCRS/2013/132 Inventory and Ecology of Fish Species of Interest

SCRS/ 2013/132 INVENTORY AND ECOLOGY OF FISH SPECIES OF INTEREST TO ICCAT IN THE SARGASSO SEA Brian E. Luckhurst¹ SUMMARY This paper provides information on the biology and ecology of a total of 18 different fish species whose distributions include the Sargasso Sea. These species are divided into four groups that correspond with ICCAT species groupings: Group 1 – Principal tuna species including yellowfin tuna, albacore tuna, bigeye tuna, bluefin tuna and skipjack tuna. Group 2 – Swordfish and billfishes including blue marlin, white marlin and sailfish, Group 3 – Small tunas including wahoo, blackfin tuna, Atlantic black skipjack tuna (Little Tunny) and dolphinfish, and Group 4 – Sharks including shortfin mako, blue, porbeagle, bigeye thresher and basking shark. For each species, information and data is provided on distribution, fishery landings, migration and movement patterns, reproduction, age and growth, food and feeding habits and ecology in relation to oceanographic parameters, primarily water temperature. The importance of Sargassum as essential fish habitat is discussed and is linked to the feeding habits of tunas and other pelagic predators . Flyingfishes are an important prey species in the diet of tunas and billfishes and as they are largely dependent on Sargassum mats as spawning habitat, the Sargasso Sea plays a fundamental role in the trophic web of highly migratory, pelagic species. KEYWORDS Sargasso Sea, Sargassum, tunas, swordfish, billfishes, sharks, biology, ecology, life history, oceanography ¹Brian E. Luckhurst, Consultant; Retired, Senior Marine Resources Officer, Government of Bermuda. Introduction The Sargasso Sea is located within the North Atlantic sub-tropical gyre and a series of currents define its boundaries with the most influential current being the Gulf Stream in the west. -

Sargassum Fusiforme (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) Has No Characteristic Stem in the Genus Sargassum

J. Jpn. Bot. 91: 33–40 (2016) Sargassum fusiforme (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) Has No Characteristic Stem in the Genus Sargassum a, b a Hiromori SHIMABUKURO *, Toshinobu TERAWAKI and Goro YOSHIDA aNational Research Institute of Fisheries and Environment of Inland Sea, Fisheries Research Agency, 2-17-5 Maruishi, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima, 739-0452 JAPAN; bNational Research Institute of Fisheries Engineering, Fisheries Research Agency, 7620-7, Hasaki, Kamisu, Ibaraki, 314-0408 JAPAN *Corresponding author: [email protected] (Accepted on July 1, 2015) Sargassum fusiforme is a very useful product for fisheries and is well known in Japan; however there are few detailed reports about its morphological characteristics. This species was initially assigned to the genus Cystophyllum and was subsequently categorized in the genus Turbinaria because of a lack of distinction between its leaves and vesicles. Recently, this species was categorized in the genus Sargassum based on the results of molecular studies; however, a debate has arisen between researchers who propose that the species belongs to the genus Sargassum and those in Japan who maintain that it belongs to the genus Hizikia. This difference in opinion is caused by a large morphological variation in the leaves among the different latitudes in which the species grows. The leaves of S. fusiforme growing in temperate regions are narrow, while those growing in low-latitude regions are lanceolate with dentate margins. The branches of Sargassum spp. generally arise from the stems on the holdfast; however, the branches of S. fusiforme arise directly from the holdfast. The biennial S. fusiforme has no stem, which is a characteristic of the genus Sargassum. -

(Mas3 Ct970111) 21

Exotics Across the Ocean - EU Concerted Action (MAS3 CT970111) 21 Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt, Sargassaceae, Fucales, Phaeophyceae Common names: Japweed, Wire weed, Strangle weed, (English), Sargassosnärje (Swedish) Sargassum muticum [after 46]. a) Winter Known coastal distribution of Sargassum muticum. morphology, b) detail branch: summer morphology, c) winter morphology, d) detail: perennial primary shoot. Impact: (* = possibly harmful, ** = harmful, *** = very harmful, ? = not known, $ = beneficial) Resources/Environment Uses of the Sea Commercial ? Commercial uses tried without much Fisheries * or Clog and foul nets, hinder to sport stocks success. $ fishery. Attract fish. Other biota ** Competing with other seaweeds. Aquaculture ** Foul ropes, lines, bags etc., grow on Seagrass beds may be second-arily molluscs and may drift away. affected by habitat changes. Difficult to spot oysters. Human health ? Can harbour epiphytic invertebrates Water * Drifting plants may block water causing allergy. abstractions intakes. Water quality * Dense canopies accumulate silt. Aquatic ** Entangle in boat propellers, tricky transport manoeuvring in beds, foul pontoons and piers. Habitat * Large, long canopies change the Tourism ** Sandy bays can become dense algal modification or habitat, reduce light and water beds. Detached plants accumulate $ movements. Shelter for animals on beaches. Vulnerable habitats: Especially sheltered to semi-exposed areas not densely covered by other seaweeds, harbours or aquaculture sites. Sandy areas with small stones, pebbles and shells, or free patches in seagrass beds. It may become established in all warm and cold temperate areas of the world in not too exposed areas, also in brackish water (at least in salinities above 16 ‰). Enhanced by polluted and nutrient-rich waters, but does not tolerate desiccation. -

Beachcombers Field Guide

Beachcombers Field Guide The Beachcombers Field Guide has been made possible through funding from Coastwest and the Western Australian Planning Commission, and the Department of Fisheries, Government of Western Australia. The project would not have been possible without our community partners – Friends of Marmion Marine Park and Padbury Senior High School. Special thanks to Sue Morrison, Jane Fromont, Andrew Hosie and Shirley Slack- Smith from the Western Australian Museum and John Huisman for editing the fi eld guide. FRIENDS OF Acknowledgements The Beachcombers Field Guide is an easy to use identifi cation tool that describes some of the more common items you may fi nd while beachcombing. For easy reference, items are split into four simple groups: • Chordates (mainly vertebrates – animals with a backbone); • Invertebrates (animals without a backbone); • Seagrasses and algae; and • Unusual fi nds! Chordates and invertebrates are then split into their relevant phylum and class. PhylaPerth include:Beachcomber Field Guide • Chordata (e.g. fi sh) • Porifera (sponges) • Bryozoa (e.g. lace corals) • Mollusca (e.g. snails) • Cnidaria (e.g. sea jellies) • Arthropoda (e.g. crabs) • Annelida (e.g. tube worms) • Echinodermata (e.g. sea stars) Beachcombing Basics • Wear sun protective clothing, including a hat and sunscreen. • Take a bottle of water – it can get hot out in the sun! • Take a hand lens or magnifying glass for closer inspection. • Be careful when picking items up – you never know what could be hiding inside, or what might sting you! • Help the environment and take any rubbish safely home with you – recycle or place it in the bin. Perth• Take Beachcomber your camera Fieldto help Guide you to capture memories of your fi nds.