Why Does Sargassum Smell So Bad? How Can Hydrogen Sulfide Affect My

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea

NICHOLAS INSTITUTE REPORT Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea L. Pendleton* F. Krowicki and P. Strosser† J. Hallett-Murdoch‡ *Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, Duke University † ACTeon ‡ Murdoch Marine October 2014 NI R 14-05 Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions Report NI R 14-05 First published October 2014 Revised April 2015 Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea L. Pendleton* F. Krowicki and P. Strosser† J. Hallett-Murdoch‡ *Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, Duke University † ACTeon ‡ Murdoch Marine Acknowledgments Support for this report was provided by the World Wide Fund for Nature Marine Protected Area Action Agenda and the Secretariat of the Sargasso Sea Commission. External peer review of the original manuscript was managed by Kristina Gjerde of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Useful comments and expert subject matter guidance were provided by Rashid Sumaila, Luke Brander, David Freestone, Howard Roe, Dan Laffoley, Brian Luckhurst, and Emilie Reuchlin-Hugenholtz. All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors alone. Additional support for Pendleton’s time was provided by the “Laboratoire d’Excellence” LabexMER (ANR-10-LABX-19) and the French government under the program Investissements d’Avenir. How to cite this report Pendleton, L., F. Krowicki., P. Strosser, and J. Hallett-Murdoch. Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea. NI R 14-05. Durham, NC: Duke University. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Sargasso Sea ecosystem generates a variety of goods and services that benefit people. -

Nutrient Bioextraction L

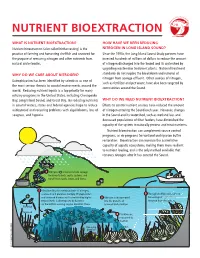

soun nd d s sla tu i d g y n o NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION l WHAT IS NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION? HOW HAVE WE BEEN REDUCING Nutrient bioextraction (also called bioharvesting) is the NITROGEN IN LONG ISLAND SOUND? practice of farming and harvesting shellfish and seaweed for Since the 1990s, the Long Island Sound Study partners have the purpose of removing nitrogen and other nutrients from invested hundreds of millions of dollars to reduce the amount natural water bodies. of nitrogen discharged into the Sound and its watershed by upgrading wastewater treatment plants. National treatment WHY DO WE CARE ABOUT NITROGEN? standards do not require the breakdown and removal of nitrogen from sewage effluent. Other sources of nitrogen, Eutrophication has been identified by scientists as one of such as fertilizer and pet waste, have also been targeted by the most serious threats to coastal environments around the communities around the Sound. world. Reducing nutrient inputs is a top priority for many estuary programs in the United States, including Chesapeake Bay, Long Island Sound, and Great Bay. By reducing nutrients WHY DO WE NEED NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION? in coastal waters, states and federal agencies hope to reduce Efforts to control nutrient sources have reduced the amount widespread and recurring problems with algal blooms, loss of of nitrogen entering the Sound each year. However, changes seagrass, and hypoxia. in the Sound and its watershed, such as wetland loss and decreased populations of filter feeders, have diminished the capacity of the system to naturally process and treat nutrients. Nutrient bioextraction can complement source control programs, as do programs for wetland and riparian buffer restoration. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

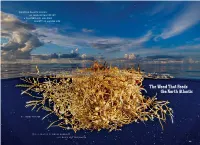

The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic

DRIFTING PLANTS KNOWN AS SARGASSUM SUPPORT A COMPLEX AND AMAZING VARIETY OF MARINE LIFE. The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic BY JAMES PROSEK PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID DOUBILET AND DAVID LIITTSCHWAGER 129 Hatchling sea turtles, like this juvenile log- gerhead, make their way from the sandy beaches where they were born toward mats of sargassum weed, finding food and refuge from predators during their first years of life. PREVIOUS PHOTO A clump of sargassum weed the size of a soccer ball drifts near Bermuda in the slow swirl of the Sargasso Sea, part of the North Atlantic gyre. A weed mass this small may shelter thousands of organisms, from larval fish to seahorses. DAVID DOUBILET (BOTH) 130 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC THE WEED THAT FEEDS THE NORTH ATLANTIC 131 ‘There’s nothing like it in any other ocean,’ says marine biologist Brian Lapointe. ‘There’s nowhere else on our blue planet that supports such diversity in the middle of the ocean—and it’s because of the weed.’ LAPOINTE IS TALKING about a floating seaweed known as sargassum in a region of the Atlantic called the Sargasso Sea. The boundaries of this sea are vague, defined not by landmasses but by five major currents that swirl in a clockwise embrace around Bermuda. Far from any main- land, its waters are nutrient poor and therefore exceptionally clear and stunningly blue. The Sargasso Sea, part of the vast whirlpool known as the North Atlantic gyre, often has been described as an oceanic desert—and it would appear to be, if it weren’t for the floating mats of sargassum. -

Kelp Cultivation Effectively Improves Water Quality and Regulates Phytoplankton Community in a Turbid, Highly Eutrophic Bay

Science of the Total Environment 707 (2020) 135561 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Kelp cultivation effectively improves water quality and regulates phytoplankton community in a turbid, highly eutrophic bay Zhibing Jiang a,b,d, Jingjing Liu a,ShangluLic,YueChena,PingDua,b,YuanliZhua,YiboLiaoa,d, Quanzhen Chen a, Lu Shou a, Xiaojun Yan e, Jiangning Zeng a,⁎, Jianfang Chen a,d a Key Laboratory of Marine Ecosystem and Biogeochemistry, State Oceanic Administration & Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China b Function Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao, China c Marine Monitoring and Forecasting Center of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, China d State Key Laboratory of Satellite Ocean Environment Dynamics, Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China e Key Laboratory of Applied Marine Biotechnology, Ministry of Education, Marine College of Ningbo University, Ningbo, China HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Kelp farming alleviated eutrophication and acidification. • Kelp farming greatly relieved light limi- tation and increased phytoplankton bio- mass. • Kelp farming appreciably enhanced phytoplankton diversity. • Kelp farming reduced the dominance of dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. • Phytoplankton community differed sig- nificantly between the kelp farm and control area. article info abstract Article history: Coastal eutrophication and its associated harmful algal blooms have emerged as one of the most severe environ- Received 19 September 2019 mental problems worldwide. Seaweed cultivation has been widely encouraged to control eutrophication and Received in revised form 11 November 2019 algal blooms. Among them, cultivated kelp (Saccharina japonica) dominates primarily by production and area. -

Quantifying Sargassum on Eastern and Western Walls of the Gulf

QUANTIFYING SARGASSUM ON EASTERN AND WESTERN WALLS OF THE GULF STREAM PROTRUDING NEAR CAPE HATTERAS INTO SARGASSO SEA BERMUDA/AZORES ABSTRACT The Sargasso Sea has been a marine life habitat for millions of years. located in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre with the western limit formed by the north and the north-eastern flowing, powerful ‘Gulf stream. The importance of the Sargasso Sea is recognized for the role of this current-system providing shelter and protection for marine animals such as fish and sea turtles. Two species of Sargassum natans and S. fluitans are highly branched with thalluses with numerous pneumatcyst that contain oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide to give buoyancy to the brownish algae. Sea surface winds cause Sargassum aggregate and form lengthy windrowed rafts to propagate. As the pneumatcyst lose their gasses, Sargassum can reach 100 meters below the sea’s surface or even accumulate on the sea floor. Accurate mapping of the boundary in the local area of the Gulf Stream near the coast of Cape Hatteras extending to Bermuda area has yet to be conducted using Earth observing Landsat satellites. Detection of these scattered aggregations of floating Sargassum suggests that this brown algae form small raft-like sea surface features In relativity to the resolution of Landsat series and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) atmospheric instruments have been found to have difficulty due to lack of spatial resolution, coverage, recurring observance, and algorithm limitations to identify pelagic species of Sargassum. Sargassum rafts, when identified, tend to be elongated and curved in the direction of the wind, and warmer than the surrounding ocean surface. -

Pelagic Sargassum Community Change Over a 40-Year Period: Temporal and Spatial Variability

Mar Biol (2014) 161:2735–2751 DOI 10.1007/s00227-014-2539-y ORIGINAL PAPER Pelagic Sargassum community change over a 40-year period: temporal and spatial variability C. L. Huffard · S. von Thun · A. D. Sherman · K. Sealey · K. L. Smith Jr. Received: 20 May 2014 / Accepted: 3 September 2014 / Published online: 14 September 2014 © The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Pelagic forms of the brown algae (Phaeo- ranging across the Sargasso Sea, Gulf Stream, and south phyceae) Sargassum spp. and their conspicuous rafts are of the subtropical convergence zone. Recent samples also defining characteristics of the Sargasso Sea in the western recorded low coverage by sessile epibionts, both calcifying North Atlantic. Given rising temperatures and acidity in forms and hydroids. The diversity and species composi- the surface ocean, we hypothesized that macrofauna asso- tion of macrofauna communities associated with Sargas- ciated with Sargassum in the Sargasso Sea have changed sum might be inherently unstable. While several biological with respect to species composition, diversity, evenness, and oceanographic factors might have contributed to these and sessile epibiota coverage since studies were con- observations, including a decline in pH, increase in sum- ducted 40 years ago. Sargassum communities were sam- mer temperatures, and changes in the abundance and distri- pled along a transect through the Sargasso Sea in 2011 and bution of Sargassum seaweed in the area, it is not currently 2012 and compared to samples collected in the Sargasso possible to attribute direct causal links. Sea, Gulf Stream, and south of the subtropical conver- gence zone from 1966 to 1975. -

Neoproterozoic Origin and Multiple Transitions to Macroscopic Growth in Green Seaweeds

Neoproterozoic origin and multiple transitions to macroscopic growth in green seaweeds Andrea Del Cortonaa,b,c,d,1, Christopher J. Jacksone, François Bucchinib,c, Michiel Van Belb,c, Sofie D’hondta, f g h i,j,k e Pavel Skaloud , Charles F. Delwiche , Andrew H. Knoll , John A. Raven , Heroen Verbruggen , Klaas Vandepoeleb,c,d,1,2, Olivier De Clercka,1,2, and Frederik Leliaerta,l,1,2 aDepartment of Biology, Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; bDepartment of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; cVlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie Center for Plant Systems Biology, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; dBioinformatics Institute Ghent, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; eSchool of Biosciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia; fDepartment of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12800 Prague 2, Czech Republic; gDepartment of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742; hDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; iDivision of Plant Sciences, University of Dundee at the James Hutton Institute, Dundee DD2 5DA, United Kingdom; jSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia, WA 6009, Australia; kClimate Change Cluster, University of Technology, Ultimo, NSW 2006, Australia; and lMeise Botanic Garden, 1860 Meise, Belgium Edited by Pamela S. Soltis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, and approved December 13, 2019 (received for review June 11, 2019) The Neoproterozoic Era records the transition from a largely clear interpretation of how many times and when green seaweeds bacterial to a predominantly eukaryotic phototrophic world, creat- emerged from unicellular ancestors (8). ing the foundation for the complex benthic ecosystems that have There is general consensus that an early split in the evolution sustained Metazoa from the Ediacaran Period onward. -

Edible Seaweed from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Edible seaweed From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Edible seaweed are algae that can be eaten and used in the preparation of food. They typically contain high amounts of fiber.[1] They may belong to one of several groups of multicellular algae: the red algae, green algae, and brown algae. Seaweeds are also harvested or cultivated for the extraction of alginate, agar and carrageenan, gelatinous substances collectively known as hydrocolloids or phycocolloids. Hydrocolloids have attained commercial significance, especially in food production as food A dish of pickled spicy seaweed additives.[2] The food industry exploits the gelling, water-retention, emulsifying and other physical properties of these hydrocolloids. Most edible seaweeds are marine algae whereas most freshwater algae are toxic. Some marine algae contain acids that irritate the digestion canal, while some others can have a laxative and electrolyte-balancing effect.[3] The dish often served in western Chinese restaurants as 'Crispy Seaweed' is not seaweed but cabbage that has been dried and then fried.[4] Contents 1 Distribution 2 Nutrition and uses 3 Common edible seaweeds 3.1 Red algae (Rhodophyta) 3.2 Green algae 3.3 Brown algae (Phaeophyceae) 3.3.1 Kelp (Laminariales) 3.3.2 Fucales 3.3.3 Ectocarpales 4 See also 5 References 6 External links Distribution Seaweeds are used extensively as food in coastal cuisines around the world. Seaweed has been a part of diets in China, Japan, and Korea since prehistoric times.[5] Seaweed is also consumed in many traditional European societies, in Iceland and western Norway, the Atlantic coast of France, northern and western Ireland, Wales and some coastal parts of South West England,[6] as well as Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. -

Values from the Resources of the Sargasso Sea

Values from the Resources of the Sargasso Sea U.R. Sumaila, V. Vats and W. Swartz CANADA USA MEXICO Number } Sargasso Sea Alliance Science Report Series When referenced this report should be referred to as: Sumaila, U. R., Vats, V., and W.Swartz. 2013. Values from the Resources of the Sargasso Sea. Sargasso Sea Alliance Science Report Series, No 12, 24 pp. ISBN 978-0-9892577-4-9 N.B The Indirect Values of the Sargasso Sea (Section 8) replace those given earlier in Laffoley, D.d’A., et al. The protection and management of the Sargasso Sea: The golden floating rainforest of the Atlantic Ocean. Summary Science and Supporting Evidence Case. Sargasso Sea Alliance, 44 pp. The Sargasso Sea Alliance is led by the Bermuda Government and aims to promote international awareness of the importance of the Sargasso Sea and to mobilise support from a wide variety of national and international organisations, governments, donors and users for protection measures for the Sargasso Sea. Further details: For further details contact Dr David Freestone (Executive Director) at [email protected] or Kate K. Morrison, (Programme Officer) at [email protected] The Secretariat of the Sargasso Sea Alliance is hosted by the Washington D.C. Office of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Suite 300, 1630 Connecticut Avenue NW, Washington D.C., 20009, USA. Website is www.sargassoalliance.org This case is being produced with generous support of donors to the Sargasso Sea Alliance: Ricardo Cisneros, Erik H. Gordon, JM Kaplan Fund, Richard Rockefeller, David E. Shaw, and the Waitt Foundation. -

Coral Reefs, Unintentionally Delivering Bermuda’S E-Mail: [email protected] fi Rst Colonists

Introduction to Bermuda: Geology, Oceanography and Climate 1 0 Kathryn A. Coates , James W. Fourqurean , W. Judson Kenworthy , Alan Logan , Sarah A. Manuel , and Struan R. Smith Geographic Location and Setting Located at 32.4°N and 64.8°W, Bermuda lies in the northwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is isolated by distance, deep Bermuda is a subtropical island group in the western North water and major ocean currents from North America, sitting Atlantic (Fig. 10.1a ). A peripheral annular reef tract surrounds 1,060 km ESE from Cape Hatteras, and 1,330 km NE from the islands forming a mostly submerged 26 by 52 km ellipse the Bahamas. Bermuda is one of nine ecoregions in the at the seaward rim of the eroded platform (the Bermuda Tropical Northwestern Atlantic (TNA) province (Spalding Platform) of an extinct Meso-Cenozoic volcanic peak et al. 2007 ) . (Fig. 10.1b ). The reef tract and the Bermuda islands enclose Bermuda’s national waters include pelagic environments a relatively shallow central lagoon so that Bermuda is atoll- and deep seamounts, in addition to the Bermuda Platform. like. The islands lie to the southeast and are primarily derived The Bermuda Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends from sand dune formations. The extinct volcano is drowned approx. 370 km (200 nautical miles) from the coastline of the and covered by a thin (15–100 m), primarily carbonate, cap islands. Within the EEZ, the Territorial Sea extends ~22 km (Vogt and Jung 2007 ; Prognon et al. 2011 ) . This cap is very (12 nautical miles) and the Contiguous Zone ~44.5 km (24 complex, consisting of several sets of carbonate dunes (aeo- nautical miles) from the same baseline, both also extending lianites) and paleosols laid down in the last million years well beyond the Bermuda Platform. -

First Report of the Asian Seaweed Sargassum Filicinum Harvey (Fucales) in California, USA

First Report of the Asian Seaweed Sargassum filicinum Harvey (Fucales) in California, USA Kathy Ann Miller1, John M. Engle2, Shinya Uwai3, Hiroshi Kawai3 1University Herbarium, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA 2 Marine Science Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara, California, USA 3 Research Center for Inland Seas, Kobe University, Rokkodai, Kobe 657–8501, Japan correspondence: Kathy Ann Miller e-mail: [email protected] fax: 1-510-643-5390 telephone: 510-387-8305 1 ABSTRACT We report the occurrence of the brown seaweed Sargassum filicinum Harvey in southern California. Sargassum filicinum is native to Japan and Korea. It is monoecious, a trait that increases its chance of establishment. In October 2003, Sargassum filicinum was collected in Long Beach Harbor. In April 2006, we discovered three populations of this species on the leeward west end of Santa Catalina Island. Many of the individuals were large, reproductive and senescent; a few were small, young but precociously reproductive. We compared the sequences of the mitochondrial cox3 gene for 6 individuals from the 3 sites at Catalina with 3 samples from 3 sites in the Seto Inland Sea, Japan region. The 9 sequences (469 bp in length) were identical. Sargassum filicinum may have been introduced through shipping to Long Beach; it may have spread to Catalina via pleasure boats from the mainland. Key words: California, cox3, invasive seaweed, Japan, macroalgae, Sargassum filicinum, Sargassum horneri INTRODUCTION The brown seaweed Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt, originally from northeast Asia, was first reported on the west coast of North America in the early 20th c. (Scagel 1956), reached southern California in 1970 (Setzer & Link 1971) and has become a common component of California intertidal and subtidal communities (Ambrose and Nelson 1982, Deysher and Norton 1982, Wilson 2001, Britton-Simmons 2004).