An Early Flyting in Hary's Wallace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf

Merge Volume 1 Article 2 2017 The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Tera Pate Follow this and additional works at: https://athenacommons.muw.edu/merge Part of the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Pate, Tara. "The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf." Merge, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 1-17. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ATHENA COMMONS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Merge by an authorized editor of ATHENA COMMONS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Image Source: “Converged” by Phil Whitehouse is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Volume 1 Spring 2017 Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1 Spring, 2017 Managing Editor: Maddy Norgard Editors: Colin Damms Cassidy DeGreen Gabrielle Lestrade Faculty Advisor: Dr. Kim Whitehead Faculty Referees: Dr. Lisa Bailey Dr. April Coleman Dr. Nora Corrigan Dr. Jeffrey Courtright Dr. Sacha Dawkins Dr. Randell Foxworth Dr. Amber Handy Dr. Ghanshyam Heda Dr. Andrew Luccassan Dr. Bridget Pieschel Dr. Barry Smith Mr. Alex Stelioes – Wills Pate 1 Tera Katherine Pate The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Old English literature is the product of a country in religious flux. Beowulf and its women are creations of this religiously transformative time, and juxtapositions of this work’s women with the women of more Pagan and, alternatively, more Christian works reveals exactly how the roles of women were transforming alongside the shifting of religious belief. -

Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing)

Programme MONDAY 30 JUNE 10.00-11.00 Plenary: Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing) 11.00-11.30 Coffee 11.30-1.00 Session 1 A) Narrating the Nation: Historiography and Identity in Stewart Scotland (c.1440- 1540): a) „Dream and Vision in the Scotichronicon‟, Kylie Murray, Lincoln College, Oxford. b) „Imagined Histories: Memory and Nation in Hary‟s Wallace‟, Kate Ash, University of Manchester. c) „The Politics of Translation in Bellenden‟s Chronicle of Scotland‟, Ryoko Harikae, St Hilda‟s College, Oxford. B) Script to Print: a) „George Buchanan‟s De jure regni apud Scotos: from Script to Print…‟, Carine Ferradou, University of Aix-en-Provence. b) „To expone strange histories and termis wild‟: the glossing of Douglas‟s Eneados in manuscript and print‟, Jane Griffiths, University of Bristol. c) „Poetry of Alexander Craig of Rosecraig‟, Michael Spiller, University of Aberdeen. 1.00-2.00 Lunch 2.00-3.30 Session 2 A) Gavin Douglas: a) „„Throw owt the ile yclepit Albyon‟ and beyond: tradition and rewriting Gavin Douglas‟, Valentina Bricchi, b) „„The wild fury of Turnus, now lyis slayn‟: Chivalry and Alienation in Gavin Douglas‟ Eneados‟, Anna Caughey, Christ Church College, Oxford. c) „Rereading the „cleaned‟ „Aeneid‟: Gavin Douglas‟ „dirty‟ „Eneados‟, Tom Rutledge, University of East Anglia. B) National Borders: a) „Shades of the East: “Orientalism” and/as Religious Regional “Nationalism” in The Buke of the Howlat and The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy‟, Iain Macleod Higgins, University of Victoria . b) „The „theivis of Liddisdaill‟ and the patriotic hero: contrasting perceptions of the „wickit‟ Borderers in late medieval poetry and ballads‟, Anna Groundwater, University of Edinburgh 1 c) „The Literary Contexts of „Scotish Field‟, Thorlac Turville-Petre, University of Nottingham. -

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

Spinning Scotland Abstr

1 ABSTRACTS FOR SPINNING SCOTLAND CONFERENCE GLASGOW UNIVERSITY - 13 th SEPTEMBER 2008 2 PANEL 1: ISLAND POETRY – ON THE FRINGE? Iain MacDonald – Linden J Bicket – Emma Dymock 9.30 – 11am Iain MacDonald The Very Heart of Beyond: Gaelic Nationalism and the Work of Fionn Mac Colla. The work of Fionn Mac Colla (Thomas Douglas Macdonald) examines the development of religious ideas and politics on Scottish society. He was primarily concerned with the representation of Scottish Gaelic and the cultural implications for Scotland with the erosion and re-establishment of Gaelic culture and identity in the industrialising modern era. These themes are most comprehensively explored in his best-known works, The Albannach (1932) and And The Cock Crew (1945) J.L. Broom's claim that MacColla's obsession with Calvinism's influence over Scotland had 'reached such proportions as to have distorted his artistic priorities' has influenced attitudes and encouraged lazy critical reception of the writer. It is my contention that MacColla's contribution to the developing 'Scottish Literary Renaissance' of the 1920s and 30s can be described as major, even if, at times, deserved critical reception has been thwarted. Mac Colla's work is primarily concerned with Scottish Gaelic culture, and its history. Although his fictional work concentrates on Gaelic communities in the central Highlands, Mac Colla spent 20 years living and teaching in the Hebrides. In this paper I will demonstrate that Mac Colla's work and themes are interwoven with his own experiences of the Gaelic community. I will also examine the title of this panel with reference to Fionn Mac Colla. -

Professor RDS Jack MA, Phd, Dlitt, FRSE

Professor R.D.S. Jack MA, PhD, DLitt, F.R.S.E., F.E.A.: Publications “Scottish Sonneteer and Welsh Metaphysical” in Studies in Scottish Literature 3 (1966): 240–7. “James VI and Renaissance Poetic Theory” in English 16 (1967): 208–11. “Montgomerie and the Pirates” in Studies in Scottish Literature 5 (1967): 133–36. “Drummond of Hawthornden: The Major Scottish Sources” in Studies in Scottish Literature 6 (1968): 36–46. “Imitation in the Scottish Sonnet” in Comparative Literature 20 (1968): 313–28. “The Lyrics of Alexander Montgomerie” in Review of English Studies 20 (1969): 168–81. “The Poetry of Alexander Craig” in Forum for Modern Language Studies 5 (1969): 377–84. With Ian Campbell (eds). Jamie the Saxt: A Historical Comedy; by Robert McLellan. London: Calder and Boyars, 1970. “William Fowler and Italian Literature” in Modern Language Review 65 (1970): 481– 92. “Sir William Mure and the Covenant” in Records of Scottish Church History Society 17 (1970): 1–14. “Dunbar and Lydgate” in Studies in Scottish Literature 8 (1971): 215–27. The Italian Influence on Scottish Literature. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1972. Scottish Prose 1550–1700. London: Calder and Boyars, 1972. “Scott and Italy” in Bell, Alan (ed.) Scott, Bicentenary Essays. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1973. 283–99. “The French Influence on Scottish Literature at the Court of King James VI” in Scottish Studies 2 (1974): 44–55. “Arthur’s Pilgrimage: A Study of Golagros and Gawane” in Studies in Scottish Literature 12 (1974): 1–20. “The Thre Prestis of Peblis and the Growth of Humanism in Scotland” in Review of English Studies 26 (1975): 257–70. -

Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age

Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands 2013 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Luke John Murphy, 2013 Reykjavík, Ísland 2013 Luke John Murphy MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Kennitala: 090187-2019 Spring 2013 ABSTRACT Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age This thesis is a study of the valkyrjur (‘valkyries’) during the late Iron Age, specifically of the various uses to which the myths of these beings were put by the hall-based warrior elite of the society which created and propagated these religious phenomena. It seeks to establish the relationship of the various valkyrja reflexes of the culture under study with other supernatural females (particularly the dísir) through the close and careful examination of primary source material, thereby proposing a new model of base supernatural femininity for the late Iron Age. The study then goes on to examine how the valkyrjur themselves deviate from this ground state, interrogating various aspects and features associated with them in skaldic, Eddic, prose and iconographic source material as seen through the lens of the hall-based warrior elite, before presenting a new understanding of valkyrja phenomena in this social context: that valkyrjur were used as instruments to propagate the pre-existing social structures of the culture that created and maintained them throughout the late Iron Age. -

Scottish Language and Literatur, Medieval and Renaissance

5 CONTENTS PREFACE 9 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 13 LANGUAGE The Concise Scots Dictionary by Mairi Robinson 19 The Pronunciation Entries for the CSD by Adam J. Aitken 35 Names Reduced to Words?: Purpose and Scope of a Dictionary of Scottish Place Names by Wilhelm F. H. Nicolaisen 47 Interlingual Communication Dutch-Frisian, a Model for Scotland? by Antonia Feitsma 55 Interscandinavian Communication - a Model for Scotland? by Kurt Braunmüller 63 Interlingual Communication: Danger and Chance for the Smaller Tongues by Heinz Kloss 73 The Scots-English Round-Table Discussion "Scots: Its Development and Present Conditions - Potential Modes of its Future" - Introductory Remarks - by Dietrich Strauss 79 The Scots-English Round-Table Discussion "Scots: Its Development and Present Conditions - Potential Modes of its Future" - Synopsis - by J. Derrick McClure 85 The Scots-English Round-Table Discussion "Scots: Its Development and Present Conditions - Potential Modes of its Future" - Three Scots Contributions - by Matthew P. McDiarmid, Thomas Crawford, J. Derrick McClure 93 Open Letter from the Fourth International Conference on Scottish Language and Literature - Medieval and Renaissance 101 What Happened to Old French /ai/ in Britain? by Veronika Kniezsa 103 6 Changes in the Structure of the English Verb System: Evidence from Scots by Hubert Gburek 115 The Scottish Language from the 16th to the 18th Century: Elphinston's Works as a Mirror of Anglicisation by Clausdirk Pollner and Helmut Rohlfing 125 LITERATURE Traces of Nationalism in Eordun's Chronicle by Hans Utz 139 Some Political Aspects of The Complaynt of Scotland by Alasdair M. Stewart 151 A Prose Satire of the Sixteenth Century: George Buchanan's Chamaeleon by John W. -

1427 to 1453

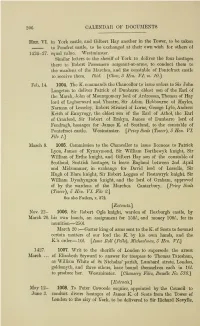

206 CALENDAE OF DOCUMENTS Hen. VI. in York castle, and Gilbert Hay another in the Tower, to be taken to Pomfret castle, to be exchanged at their own wish for others of 1426-27. equal value. Westminster. Similar letters to the sheriff of York to deliver the four hostages there to Eobert Passemere sergeant-at-arms, to conduct them to the wardens of the Marches, and the constable of Pontefract castle to receive them. IMd. {^Closc, 5 Hen. VI. m. JO.] Feb. 14. 1004. The K. commands the Chancellor to issue orders to Sir John Langeton to deliver Patrick of Dunbarre eldest son of the Earl of the March, John of Mountgomery lord of Ardrossan, Thomas of Hay lord of Loghorward and Yhestre, Sir Adam Hebbourne of Hayles, Norman of Lesseley, Eobert Stiward of Lome, George Lyle, Andrew Keith of Ennyrugy, the eldest son of the Earl of Athol, the Earl of Crauford, Sir Eobert of Erskyn, James of Dunbarre lord of Fendragh, hostages for James K. of Scotland, to the constable of Pontefract castle. Westminster. {^Privy Seals (Toiuer), 5 Hen. VI. File I] March 8. 1005. Commission to the Chancellor to issue licences to Patrick Lyon, James of Kynnymond, Sir William Borthewyk knight, Sir William of Erthe knight, and Gilbert Hay son of the constable of Scotland, Scottish hostages, to leave England between 2nd April and Midsummer, in exchange for David lord of Lesselle, Sir Hugh of Blare knight. Sir Eobert Loggan of Eestawryk knight, Sir William Dysshyngton knight, and the lord of Graham, approved of by the wardens of the Marches. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage' Jacquelyn Hendricks Santa Clara University

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 43 | Issue 2 Article 21 12-15-2017 Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage' Jacquelyn Hendricks Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Hendricks, Jacquelyn (2017) "Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage'," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, 220–236. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol43/iss2/21 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GAVIN DOUGLAS’S AENEADOS: CAXTON’S ENGLISH AND "OUR SCOTTIS LANGAGE" Jacquelyn Hendricks In his 1513 translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, titled Eneados, Gavin Douglas begins with a prologue in which he explicitly attacks William Caxton’s 1490 Eneydos. Douglas exclaims that Caxton’s work has “na thing ado” with Virgil’s poem, but rather Caxton “schamefully that story dyd pervert” (I Prologue 142-145).1 Many scholars have discussed Douglas’s reaction to Caxton via the text’s relationship to the rapidly spreading humanist movement and its significance as the first vernacular version of Virgil’s celebrated epic available to Scottish and English readers that was translated directly from the original Latin.2 This attack on Caxton has been viewed by 1 All Gavin Douglas quotations and parentheical citations (section and line number) are from D.F.C. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Cultural Exchange: from Medieval

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 1: Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: from Medieval to Modernity AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: Medieval to Modern Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative and The Stout Research Centre Irish-Scottish Studies Programme Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 1753-2396 Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Issue Editor: Cairns Craig Associate Editors: Stephen Dornan, Michael Gardiner, Rosalyn Trigger Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Michael Brown, University of Aberdeen Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Brad Patterson, Victoria University of Wellington Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal, published twice yearly in September and March, by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. An electronic reviews section is available on the AHRC Centre’s website: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrc- centre.shtml Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be addressed to The Editors,Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, Humanity Manse, 19 College Bounds, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UG or emailed to [email protected] Subscriptions and business correspondence should be address to The Administrator.