A Necessary Condition for the Survival of Democracy†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2216Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150023 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘AN ENDLESS VARIETY OF FORMS AND PROPORTIONS’: INDIAN INFLUENCE ON BRITISH GARDENS AND GARDEN BUILDINGS, c.1760-c.1865 Two Volumes: Volume I Text Diane Evelyn Trenchard James A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of History of Art September, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… vi Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. viii . Glossary of Indian Terms ……………………………………………………....... ix List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………... xvii Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 1 1. Chapter 1: Country Estates and the Politics of the Nabob ………................ 30 Case Study 1: The Indian and British Mansions and Experimental Gardens of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal …………………………………… 48 Case Study 2: Innovations and improvements established by Sir Hector Munro, Royal, Bengal, and Madras Armies, on the Novar Estate, Inverness, Scotland …… 74 Case Study 3: Sir William Paxton’s Garden Houses in Calcutta, and his Pleasure Garden at Middleton Hall, Llanarthne, South Wales ……………………………… 91 2. Chapter 2: The Indian Experience: Engagement with Indian Art and Religion ……………………………………………………………………….. 117 Case Study 4: A Fairy Palace in Devon: Redcliffe Towers built by Colonel Robert Smith, Bengal Engineers ……………………………………………………..…. -

Application of the Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA)

Application of the Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) to assess the ethnobotany and forest conservation status of the Zarghoon Juniper Ecosystem, Balochistan, Pakistan Uso del enfoque de valuación rural participativa (PRA) para evaluar el estado de conservación del bosque y etnobotánica del Ecosistema de Junípero Zarghoon, Balochistan, Pakistan Bazai ZA1, RB Tareen1, AKK Achakzai1, H Batool2 Abstract. The data collection approach called Participatory Rural Resumen. El enfoque de recolección de datos llamado Valuación Appraisal (PRA) was used in five villages: Killi Tor Shore; Medadzai; Rural con Participantes (PRA) se utilizó en cinco villas: Killi Tor Ghunda; Kala Ragha, and Killi Shaban. Up to five groups were Shore; Medadzai; Ghunda; Kala Ragha y Killi Shaban. En cada villa sampled in each village, comprising a total of 17 villages within the se muestrearon hasta cinco grupos, comprendiendo un total de 17 Zarghoon Juniper ecosystem. This area is rich both historically and villas en el ecosistema de junípero de Zarghoon. Esta área es rica culturally for using medicinal plants, mostly by women (60%). In this tanto histórica como culturalmente por el uso de plantas medicinales, study, 26 species of medicinal plants fit in 20 genera and 13 families. principalmente por mujeres (60%). En este estudio, 26 especies de They are used by aboriginal people via the indigenous knowledge plantas medicinales pertenecieron a 20 géneros y 13 familias. Estas they have for the treatment of many diseases. About 60, 35, and 5% son utilizadas por aborígenes a través del conocimiento indígena que of the medicines are prepared to be used orally, topically and boiled ellos tienen para el tratamiento de varias enfermedades. -

06122003 Dt Mpr 01 D L C

DLD‰†‰KDLD‰†‰DLD‰†‰MDLD‰†‰C THE TIMES OF INDIA Bottoms up: find your THE TIMES OF INDIA Kylie Minogue first name Saturday, goes Slow now! initial here Man returns ‘bad-luck’ glass to temple December 6, 2003 A German tourist, who to- gen’s mother died, his wife Page 7 ok a piece of decorative gl- divorced him and he lost ass from Bangkok’s temple money,’’ informs secretary of the Emerald Buddha, at the Thai culture ministry has now sent the fr- Chakrarot Chitra- agment back after bongs. two years of bad lu- Now, having retu- ck. The tourist iden- rned the glass to tifies himself as Ju- the Tourism Autho- ergen Z. rity of Thailand, Ju- ‘‘After returning ergen’s luck might to his country, Juer- just be a glass apart! OF INDIA MANOJ KESHARWANI Polls apart, Dikshit INDIA ISN’T A SAFE BET! rom contender to pretend- field day — but there’s a catch. er.Team India might plan SATTA SCORE Constant surveillance and cont- promises to deliver Fto steal the Aussies’ thu- The odds are stacked inuous raids by the police and nder while Down Under, but de- other law-enforcement agencies ARUN KUMAR DAS sounds cliched, Dikshit reit- si bookies believe that the ongo- against India in the ongoing has spread panic in the betting Times News Network erates her stance: ‘‘I want to ing series will be a one-sided af- series against Australia bazaar. ‘‘While we are forced to make the capital of the coun- fair. Satta-operators are betting shift our hideouts constantly rom jeers to cheers. -

Public Sector Development Programme 2019-20 (Original)

GOVERNMENT OF BALOCHISTAN PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT PUBLIC SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2019-20 (ORIGINAL) Table of Contents S.No. Sector Page No. 1. Agriculture……………………………………………………………………… 2 2. Livestock………………………………………………………………………… 8 3. Forestry………………………………………………………………………….. 11 4. Fisheries…………………………………………………………………………. 13 5. Food……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 6. Population welfare………………………………………………………….. 16 7. Industries………………………………………………………………………... 18 8. Minerals………………………………………………………………………….. 21 9. Manpower………………………………………………………………………. 23 10. Sports……………………………………………………………………………… 25 11. Culture……………………………………………………………………………. 30 12. Tourism…………………………………………………………………………... 33 13. PP&H………………………………………………………………………………. 36 14. Communication………………………………………………………………. 46 15. Water……………………………………………………………………………… 86 16. Information Technology…………………………………………………... 105 17. Education. ………………………………………………………………………. 107 18. Health……………………………………………………………………………... 133 19. Public Health Engineering……………………………………………….. 144 20. Social Welfare…………………………………………………………………. 183 21. Environment…………………………………………………………………… 188 22. Local Government ………………………………………………………….. 189 23. Women Development……………………………………………………… 198 24. Urban Planning and Development……………………………………. 200 25. Power…………………………………………………………………………….. 206 26. Other Schemes………………………………………………………………… 212 27. List of Schemes to be reassessed for Socio-Economic Viability 2-32 PREFACE Agro-pastoral economy of Balochistan, periodically affected by spells of droughts, has shrunk livelihood opportunities. -

Category Wise Lists Private.Xlsx

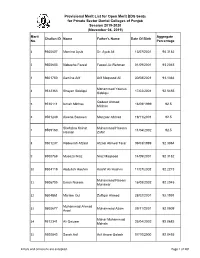

Provisional Merit List for Open Merit BDS Seats for Private Sector Dental Colleges of Punjab Session 2019-2020 (November 04, 2019) Merit Aggregate Challan ID Name Father's Name Date Of Birth No. Percentage 1 9500607 Momina Ayub Dr. Ayub Ali 13/07/2001 94.3182 2 9505653 Nabeeha Fazeel Fazeel-Ur-Rehman 01/09/2001 93.2045 3 9501750 Aamina Arif Arif Maqsood Ali 30/08/2001 93.1364 Mohammad Younus 4 9512363 Shayan Siddiqui 17/02/2001 92.5455 Siddiqui Qadeer Ahmad 5 9510111 Ismah Minhas 16/09/1999 92.5 Minhas 6 9501249 Aleena Sameen Manzoor Ahmad 19/11/2001 92.5 Shehzina Kainat Muhammad Hassan 7 9509160 11/04/2002 92.5 Hassan Zafar 8 9501237 Hadeerah Afzaal Afzaal Ahmed Tarar 09/03/1999 92.3864 9 9500769 Mueeza Niaz Niaz Maqsood 14/09/2001 92.3182 10 9504119 Abdullah Hashmi Kashif Ali Hashmi 17/07/2002 92.2273 Muhammad Naeem 11 9506705 Eman Naeem 16/08/2002 92.2045 Munawar 12 9504861 Mariam Gul Zulfiqar Ahmed 28/02/2001 92.1591 Muhammad Ahmad 13 9500677 Muhammad Azam 09/11/2001 92.0909 Arsal Mahar Muhammad 14 9512341 Ali Qaizaar 25/04/2002 92.0682 Mohsin 15 9500843 Sarah Arif Arif Anwar Baloch 07/10/2000 92.0455 Errors and omissions are excepted. Page 1 of 281 Provisional Merit List for Open Merit BDS Seats for Private Sector Dental Colleges of Punjab Session 2019-2020 (November 04, 2019) Merit Aggregate Challan ID Name Father's Name Date Of Birth No. Percentage 16 9504077 Wajiha Irshad Khan Irshad Ahmad Shahid 01/09/1998 92 17 9510788 Saba Kainat Azmat Javed 16/11/1997 91.9773 18 9512545 Mohammad Anas Ijaz Ijaz Ahmad 17/12/1999 91.9773 19 9508344 -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Government of Balochistan Audit Year 2014-15

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF GOVERNMENT OF BALOCHISTAN AUDIT YEAR 2014-15 AUDITOR-GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS i PREFACE iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY v SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ix I: Audit Work Statistics ix II: Audit observations regarding Financial Management ix III: Outcome statistics x IV: Table of irregularities pointed out xi Chapter 1 1 1.1 Public Financial Management Issues (AG Balochistan, Quetta) 1 Chapter 2 9 2.1 Agriculture and Cooperatives Department 9 2.1.1 Introduction 9 2.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) 9 2.1.3 Brief comments on the status of compliance with PAC directives 9 2.2 AUDIT PARAS 10 Chapter 3 27 3 Autonomous Bodies 27 3.1 Balochistan Development Authority 27 3.1.1 Introduction 27 3.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) 27 3.1.3 Brief comments on the status of compliance with PAC directives 27 3.2 AUDIT PARAS 28 3.3 Balochistan Coastal Development Authority 36 3.3.1 Introduction 36 3.3.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) 36 3.3.3 Brief comments on the status of compliance with PAC directives 36 3.4 AUDIT PARAS 36 3.5 Balochistan Employees Social Security Institute 44 3.5.1 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) 44 3.5.2 Brief comments on the status of compliance with PAC directives 44 3.7.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) 50 3.7.3 Brief comments on the status of compliance with PAC directives 50 3.8 AUDIT PARAS 50 3.9 Gawadar Development Authority 52 3.9.1 Introduction 52 3.9.2 Comments -

The Tyabji Clan—Urdu As a Symbol of Group Identity by Maren Karlitzky University of Rome “La Sapienza”

The Tyabji Clan—Urdu as a Symbol of Group Identity by Maren Karlitzky University of Rome “La Sapienza” T complex issue of group identity and language on the Indian sub- continent has been widely discussed by historians and sociologists. In particular, Paul Brass has analyzed the political and social role of language in his study of the objective and subjective criteria that have led ethnic groups, first, to perceive themselves as distinguished from one another and, subsequently, to demand separate political rights.1 Following Karl Deutsch, Brass has underlined that the existence of a common language has to be considered a fundamental token of social communication and, with this, of social interaction and cohesion. 2 The element of a “national language” has also been a central argument in European theories of nationhood right from the emergence of the concept in the nineteenth century. This approach has been applied by the English-educated élites of India to the reality of the Subcontinent and is one of the premises of political struggles like the Hindi-Urdu controversy or the political claims put forward by the Muslim League in promoting the two-nations theory. However, in Indian society, prior to the socio-political changes that took place during the nineteenth century, common linguistic codes were 1Paul R. Brass has studied the politics of language in the cases of the Maithili movement in north Bihar, of Urdu and the Muslim minority in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and of Panjabi in the Hindu-Sikh conflict in Punjab. Language, Religion and Politics in North India (London: Cambridge University Press, ). -

Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand an Everlasting Personality

TAKATOOT Issue 5Volume 3 20 January - June 2011 Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand An Everlasting Personality Dr. Hanif Khalil Abstract: Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand was a renowned intellectual and politician of the sub-continent among the pashtoon celebrities. He was a poet, critic, researcher, Journalist and translator of Pashto literature at a time. Apart from this he was a practical politician and a freedom fighter. Kakaji Sanobar played a vital role in the reawakening of the pashtoons as well as the other minorities against the British imperialism and the cruel and unjust policies of the Britishers in the sub continent. He used his journalistic abilities and his journal the monthly Aslam as well as his writings in prose and verses for achieving the targets to his real mission. For the fulfillment of this purpose he remained in jails for several years. He gave a lot of sacrifices, faces many hurdles and difficulties, but no one could remove him from his firm determination. In this paper the author has elaborated the major achievements and surveyed the practical steps and sacrifices of this legendary personality of the 20 th century. This paper is actually a tribute to Kakaji Sanobar Hussain the stalwart personality of pashtoon nation . I declare, that among the genius personalities of Pashtun nation, after khushal Khan Khattak, Kakaji Sanobar Hussain is a personality which could be accepted as a multi-dimensional celebrity. For the acceptance of that declaration, I would say that Kakaji was not only a great man but also a great Politician, Writer, Journalist and a Social Worker simultaneously. -

![South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online Since 15 December 2019, Connection on 24 March 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0491/south-asia-multidisciplinary-academic-journal-22-2019-student-politics-in-south-asia-online-online-since-15-december-2019-connection-on-24-march-2021-510491.webp)

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online Since 15 December 2019, Connection on 24 March 2021

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 22 | 2019 Student Politics in South Asia Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalyté (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5852 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.5852 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalyté (dir.), South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online since 15 December 2019, connection on 24 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5852; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj. 5852 This text was automatically generated on 24 March 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Generational Communities: Student Activism and the Politics of Becoming in South Asia Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalytė Student Politics in British India and Beyond: The Rise and Fragmentation of the All India Student Federation (AISF), 1936–1950 Tom Wilkinson A Campus in Context: East Pakistan’s “Mass Upsurge” at Local, Regional, and International Scales Samantha Christiansen Crisis of the “Nehruvian Consensus” or Pluralization of Indian Politics? Aligarh Muslim University and the Demand for Minority Status Laurence Gautier Patronage, Populism, and Protest: Student Politics in Pakistani Punjab Hassan Javid The Spillovers of Competition: Value-based Activism and Political Cross-fertilization in an Indian Campus Jean-Thomas Martelli Regional Charisma: The Making of a Student Leader in a Himalayan Hill Town Leah Koskimaki Performing the Party. National Holiday Events and Politics at a Public University Campus in Bangladesh Mascha Schulz Symbolic Boundaries and Moral Demands of Dalit Student Activism Kristina Garalytė How Campuses Mediate a Nationwide Upsurge against India’s Communalization. -

Flashpoint: Pakistan in Crisis

To approach Rabwah, home to Pakistan’s minority Ahmadi sect, it is necessary to pass through Chiniot, an ancient town said to have been first populated by Alexander the Great of Macedonia, in 326 BC . Today, Chiniot, which stands amidst the lush green countryside of the Punjab province, is known chiefly for its skilled furniture craftsmen. The town is a bustling, but run-down urban centre – the cascading monsoon rain failing to wash away the grime and squalor that hangs all around. It is on the peeling, yellow-plastered walls of Chiniot that the first signs of the hatred directed against the Ahmadi community appear. The movement – named for its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian (located in the Indian Punjab) – Karachi broke away from mainstream Islam in 1889. The slogans, etched out in the flowing Urdu script, call on Muslims to ‘Kill Ahmadi non-believers’. apparent every official building is heavily fortified – Rabwah, a town of some 50,000 people, houses even the holy places and the parks – testifying to the the largest concentration of Ahmadis in Pakistan. fact that Rabwah remains a town under siege. Flashpoint Overall, there are an estimated 1.5 million Ahmadis While the 1974 decision against Ahmadis was met in the country amongst a population of 55 million by anger within the community, worse was to come. In people. Rabwah was built on 1,000 acres of land 1984, military dictator General Zia ul-Haq, as part of purchased from the Pakistan government in 1948 by policies aimed at ‘Islamizing’ the country, introduced a Pakistan in Crisis: the Ahmaddiya Muslim community, to house set of laws that, among other restrictions, barred Ahmadis who were forced to leave India amidst the Ahmadis from preaching their faith, calling their places tumultuous partition of the subcontinent in 1947, of worship ‘masjids’ (the term used by mainstream which resulted in the creation of the mainly Muslim Muslims) and from calling themselves Muslim. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

MARCH 2021 Current Affairs Best Revision Questions

MARCH 2021 Current Affairs Best Revision Questions Q) Consider the following statements. a) ISRO successfully launched Brazil’s optical earth observation satellite, Amazonia-1, and 18 co-passenger satellites b) The satellites were carried onboard the PSLV-C51, the 53rd flight of ISRO’s launch vehicle and the first dedicated mission of its commercial arm, NewSpace India Ltd. Which of the above statements is/are correct? A. 1 only B. 2 only C. Both 1 and 2 D. Neither 1 nor 2 Ans - C The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) on Sunday successfully launched Brazil’s optical earth observation satellite, Amazonia-1, and 18 co-passenger satellites — five from India and 13 from the U.S. — from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre at Sriharikota. The satellites were carried onboard the PSLV-C51, the 53rd flight of ISRO’s launch vehicle, and the first dedicated mission of its commercial arm, NewSpace India Ltd. The mission was undertaken under a commercial arrangement with Spaceflight Inc., U.S. Q) Consider the following statements: a) Indian Air Force will perform at an airshow at the Galle Face in Colombo as part of the 70th-anniversary celebrations of the Sri Lankan Air Force (SLAF) b) This is the first performance for the Suryakiran Aerobatic Team (SKAT) outside India since it was resurrected in 2015 with the Hawk advanced jet trainers. Which of the above statements is/are correct? A. 1 only 1 TELEGRAM LINK: https://t.me/opdemy WEBSITE: www.opdemy.com B. 2 only C. Both 1 and 2 D. Neither 1 nor 2 Anc - C The Suryakiran Aerobatic Team (SKAT) and the Sarang helicopter display team, along with the light combat aircraft, of the Indian Air Force, will perform at an airshow at the Galle Face in Colombo from March 3 to 5 as part of the 70th-anniversary celebrations of the Sri Lankan Air Force (SLAF).