Stocks As Money: Convenience Yield and the Tech-Stock Bubble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3Com Homeconnect Pc Digital Camera

© 2001. All rights reserved. Black Box Corporation. Black Box Corporation • 1000 Park Drive • Lawrence, PA 15055-1018 • Tech Support: 724-746-5500 • www.blackbox.com • e-mail: [email protected] 3COM HOMECONNECT PC DIGITAL CAMERA Have a face-to-face conversation with your out-of- state relative or a co-worker down the hall—all without leaving your chair. Key Features ometimes an email just isn’t In addition, you can view your the images so that the picture Camera uses your PC’s Senough. For some conver- coworkers in return. See and talk looks brighter and clearer. USB port. sations, you need interact face to to several people—all in different Requirements include a PC face. But what if the person you places—simultaneously, using with at least a 166-MHz Supports 24- or 16-bit need to talk to is halfway around your phone line or the Internet. processor, 32 MB of RAM, a USB video. Uses DSP for the country? Then what? The Camera operates with port, and a CD-ROM drive. high-quality images. Before you make hotel plug-and-play installation. Simply Software on the included CD- reservations, pack your suitcase, plug it into your PC’s USB port and ROM gives you extensive video It’s easy to install and and board your flight, check out install the included software. capabilities, including video perform video editing, the 3Com HomeConnect PC Because of its slim design, the phone calls, video e-mail, enhance photos, and Digital Camera. Use it to project camera takes up minimal space multiparty video chat, and video have interactive your voice and a full-motion video on your PC. -

Multimedia, Internet, On-Line

Section IV: Multimedia, the Internet, and On-Line Services High-End Digital Video Applications Larry Amiot Electronic and Computing Technologies Division Argonne National Laboratory The emphasis of this paper is on the high-end applications Internet and Intranet that are driving digital video. The research with which I am involved at Argonne National Laboratory is not done on dig- The packet video networks which currently support many ital video per se, but rather on how the research applications applications such as file transfer, Mbone video (talking at the laboratory drive its requirements for digital video. The heads), and World Wide Web browsing are limiting for high- paper will define what digital video is, what some of its com- quality video because of the low throughput one can achieve ponents are, and then discuss a few applications that are dri- via the Internet or intranets. Examples of national packet ving the development of these components. The focus will be switched networks developed in the last several years include on what digital video means to individuals in the research the National Science Foundation Network (NSFNet). The and education community. Department of Energy had its own network called ESNET, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration The Digital Video Environment (NASA) had a network as well. Recently, the NSFNet was de- commissioned, and commercial interests are now starting to In 1996, a group of people from several universities in the fill that void. Research and education communities are find- Midwest and from Argonne formed a Video Working Group. ing, however, that this new commercial Internet is too re- This body tried to define the areas of digital video of impor- stricting and does not meet their throughput requirements; it tance to their institutions. -

3Com® Asterisk® Appliance

3Com® Asterisk® Appliance Administrator’s Guide Release 1.4 Part Number 900-0467-01 Published October 2007 http://www.3com.com/ 3Com Corporation Copyright © 2007, 3Com Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this 350 Campus Drive documentation may be reproduced in any form or by any means or used to make any derivative work (such as translation, transformation, or adaptation) without written Marlborough, MA permission from 3Com Corporation. 01752-3064 3Com Corporation reserves the right to revise this documentation and to make changes in content from time to time without obligation on the part of 3Com Corporation to provide notification of such revision or change. 3Com Corporation provides this documentation without warranty, term, or condition of any kind, either implied or expressed, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties, terms, or conditions of merchantability, satisfactory quality, and fitness for a particular purpose. 3Com may make improvements or changes in the product(s) and/or the program(s) described in this documentation at any time. If there is any software on removable media described in this documentation, it is furnished under a license agreement included with the product as a separate document, in the hardcopy documentation, or on the removable media in a directory file named LICENSE.TXT or !LICENSE.TXT. If you are unable to locate a copy, please contact 3Com and a copy will be provided to you. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT LEGEND If you are a United States government agency, then this documentation and the software described herein are provided to you subject to the following: All technical data and computer software are commercial in nature and developed solely at private expense. -

Warren Adelman Godaddy.Com 14455 N.Hayden Rd Scottsdale, AZ 85255 Office: (480)505-8835

Warren Adelman GoDaddy.com 14455 N.Hayden Rd Scottsdale, AZ 85255 Office: (480)505-8835 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE GODADDY GROUP, INC Scottsdale, AZ President and Chief Operating Officer, February 2006 To Present Responsible for day-to-day operations, resource management, process improvement and corporate strategic planning. Warren also heads up the Governance and Policy Committee, which is dedicated to oversight of Go Daddy's standards and practices. During service at Go Daddy, contributed to 53 patent filings related to Go Daddy products, services and business processes. Drove initiative to form registry/registrar joint venture to promote the Montengrin ccTLD, dotME. Also serves as a Director of the Go Daddy Board from May 2006 to present. Chief Operating Officer, October 2004 To February 2006 Assumed responsibility for additional groups within Go Daddy including human resources, ICANN policy planning and the Go Daddy customer care group. Go Daddy’s 1500 person customer care center fields some 1 million calls per month. It is a cornerstone of Go Daddy’s growth strategy and in addition to providing 24/7 365 telephone and email support, the customer care group generates significant revenues. Vice President, Product and Strategic Development, September 2003 to October 2004 Assumed expanded role for product development of suite of on-demand web presence services targeted at SMBs. This included hosting, email, online marketing tools, domain add-ons, and productivity tools. Go Daddy’s hosting offering including Shared, Grid, Dedicated and Virtual Dedicated is the largest in the world. In this role I also assumed responsibility for Go Daddy’s IT infrastructure with a focus on expansion, resilience, and stability. -

Cornell Dyson Wp0611

WP 2006-11 May 2006 Working Paper Department of Applied Economics and Management Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7801 USA Bubbles or Convenience Yields? A Theoretical Explanation with Evidence from Technology Company Equity Carve-Outs Vicki Bogan It is the Policy of Cornell University actively to support equality of educational and employment opportunity. No person shall be denied admission to any educational program or activity or be denied employment on the basis of any legally prohibited discrimination involving, but not limited to, such factors as race, color, creed, religion, national or ethnic origin, sex, age or handicap. The University is committed to the maintenance of affirmative action programs which will assure the continuation of such equality of opportunity. Bubbles or Convenience Yields? A Theoretical Explanation with Evidence from Technology Company Equity Carve-Outs Vicki Bogan¤ This Version: March 2006 Abstract This paper offers an alternative explanation for what is typically referred to as an asset pricing bubble. We develop a model that formalizes the Cochrane (2002) convenience yield theory of technology company stocks to explain why a rational agent would buy an “overpriced” security. Agents have a desire to trade but short-sale restrictions and other frictions limit their trading strategies and enable prices of two similar securities to be different. Thus, divergent prices for similar securities can be sustained in a rational expectations equilibrium. The paper also provides empirical support for the model using a sample of 1996 - 2000 equity carve-outs. (JEL: G10, G12, D50) Keywords: Asset Pricing, Rational Bubbles ¤Department of Applied Economics and Management, 454 Warren Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853. -

For Continuous-Time Models in Economics and Finance, We Want To

Chapter 3 — Arbitrage and Pricing Arbitrage is a very important and simple concept used in finance to pin down possible prices. It is simple to use because the existence or absence of arbitrage does not rely upon anyone’s subjective probability beliefs, apart from agreement on what is possible and impossible. Nor does it rely upon anyone’s utility, apart from the assumption that all prefer more money to less. An arbitrage is a portfolio of assets with a zero or negative current costs and an outcome guaranteed to be nonnegative. At least one of the possible outcomes or the cost must differ from zero otherwise arbitrage would include the trivial “nothing” portfolio that made no purchase and received nothing. It is natural to preclude the existence of arbitrage opportunities in Finance as its existence would mean that arbitrarily large amounts of money could be extracted from the set of assets either now or later. Any investor would always wish to add an arbitrage to his portfolio as it would never increase the cost and never reduce any payoff. The desire of every investor to purchase any arbitrage should increase its cost until it ceases to be an arbitrage. A concept closely related to arbitrage is dominance. One random variable dominates another if it is never smaller and can be larger. If the payoffs on one asset or portfolio dominate some other another and the first costs no more, there is an arbitrage consisting of buying the dominating asset and selling the dominated one. Perhaps the first lesson learned is Finance is how to compute a present value. -

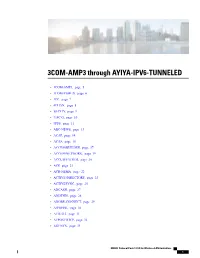

3COM-AMP3 Through AYIYA-IPV6-TUNNELED

3COM-AMP3 through AYIYA-IPV6-TUNNELED • 3COM-AMP3, page 5 • 3COM-TSMUX, page 6 • 3PC, page 7 • 4CHAN, page 8 • 58-CITY, page 9 • 914C G, page 10 • 9PFS, page 11 • ABC-NEWS, page 13 • ACAP, page 14 • ACAS, page 16 • ACCESSBUILDER, page 17 • ACCESSNETWORK, page 19 • ACCUWEATHER, page 20 • ACP, page 21 • ACR-NEMA, page 22 • ACTIVE-DIRECTORY, page 23 • ACTIVESYNC, page 25 • ADCASH, page 27 • ADDTHIS, page 28 • ADOBE-CONNECT, page 29 • ADWEEK, page 30 • AED-512, page 31 • AFPOVERTCP, page 32 • AGENTX, page 33 NBAR2 Protocol Pack 12.0.0 for Wireless LAN Controllers 1 3COM-AMP3 through AYIYA-IPV6-TUNNELED • AIRBNB, page 34 • AIRPLAY, page 35 • ALIWANGWANG, page 36 • ALLRECIPES, page 38 • ALPES, page 39 • AMANDA, page 41 • AMAZON, page 42 • AMEBA, page 43 • AMAZON-INSTANT-VIDEO, page 44 • AMAZON-WEB-SERVICES, page 45 • AMERICAN-EXPRESS, page 47 • AMINET, page 48 • AN, page 49 • ANCESTRY-COM, page 51 • ANDROID-UPDATES, page 52 • ANET, page 54 • ANSANOTIFY, page 55 • ANSATRADER, page 56 • ANY-HOST-INTERNAL, page 58 • AODV, page 59 • AOL-MESSENGER, page 60 • AOL-MESSENGER-AUDIO, page 62 • AOL-MESSENGER-FT, page 63 • AOL-MESSENGER-VIDEO, page 64 • AOL-PROTOCOL, page 65 • APC-POWERCHUTE, page 66 • APERTUS-LDP, page 68 • APPLEJUICE, page 69 • APPLE-APP-STORE, page 71 • APPLE-IOS-UPDATES, page 73 • APPLE-REMOTE-DESKTOP, page 74 • APPLE-SERVICES, page 76 • APPLE-TV-UPDATES, page 77 NBAR2 Protocol Pack 12.0.0 for Wireless LAN Controllers 2 3COM-AMP3 through AYIYA-IPV6-TUNNELED • APPLEQTC, page 78 • APPLEQTCSRVR, page 80 • APPLIX, page 81 • ARCISDMS, page -

An Introduction to Internet Radio

NB: This version was updated with new Internet Radio products on 26 October 2005 (see page 8). INTERNET RADIO AnInternet introduction to Radio Franc Kozamernik and Michael Mullane EBU This article – based on an EBU contribution to the WBU-TC Digital Radio Systems Handbook – introduces the concept of Internet Radio (IR) and provides some technical background. It gives examples of IR services now available in different countries and provides some guidance for traditional radio broadcasters on how to adapt to the rapidly changing multimedia environment. Traditionally, audio programmes have been available via dedicated terrestrial networks broad- casting to radio receivers. Typically, they have operated on AM and FM terrestrial platforms but, with the move to digital broadcasting, audio programmes are also available today via DAB, DRM and IBOC (e.g. HD Radio in the USA). However, this paradigm is about to change. Radio programmes are increasingly available not only from terrestrial networks but also from a large variety of satellite, cable and, indeed, telecommunications networks (e.g. fixed telephone lines, wire- less broadband connections and mobile phones). Very often, radio is added to digital television plat- forms (e.g. DVB-S and DVB-T). Radio receivers are no longer only dedicated hi-fi tuners or portable radios with whip aerials, but are now assuming the shape of various multimedia-enabled computer devices (e.g. desktops, notebooks, PDAs, “Internet” radios, etc.). These sea changes in radio technologies impact dramatically on the radio medium itself – the way it is produced, delivered, consumed and paid-for. Radio has become more than just audio – it can now contain associated metadata, synchronized slideshows and even short video clips. -

A Learning Agent for Wireless News Access

A Learning Agent for Wireless News Access Daniel Billsus, Michael J. Pazzani and James Chen Department of Information and Computer Science University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA 92697 +1 949 824 3491 {dbillsus, pazzani, jamesfc}@ics.uci.edu ABSTRACT conditions -- wireless information transmission is expensive. We describe a user interface for wireless information devices, Service providers charge users based on the amount of data specifically designed to facilitate learning about users’ individual transmitted, turning wireless information access into a costly interests in daily news stories. User feedback is collected luxury compared to regular Internet access. For example, unobtrusively to form the basis for a content-based machine transmission costs for 3Com’s Palm VII amount to approximately learning algorithm. As a result, the described system can adapt to $25 per month for 150KB, and an extra charge of 20 cents for users’ individual interests, reduce the amount of information that each additional KB. We believe that intelligent information agents needs to be transmitted, and help users access relevant have the potential to significantly reduce the amount and cost of information with minimal effort. data transmitted, and will therefore be of paramount importance for ubiquitous information access applications. Agents that know Keywords about users’ interests and preferences can simplify information Wireless, intelligent information access, news, user modeling, access tasks substantially. machine learning. In this paper, we focus on a learning agent designed to help users access interesting news stories. We use 3Com’s Palm VII 1. INTRODUCTION organizer as an example of a wireless information device, noting Driven by the explosive growth of information available on the that the learning approach and interface design reported here Internet, intelligent information access has become a central generalize to other devices such as cell phones or two-way pagers. -

Palm Covers4

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 < leadership, strength and commitment > the palm economy Through the success of our Palm OS® platform, Palm has created a large ecosystem of companies that create and sell a variety of software applications, peripherals and accessories for Palm OS based devices. This thriving community offers a wealth of solutions for consumer, professional and enterprise users and remains one of the key components in our value proposition to our present and future customers. < 225,000+ developers* and 14,000+ applications* > *As of 7/2002 Peripherals and expansion cards sold separately. As Palm started FY ’02, we faced three fundamental • We continued to enhance pro forma operating results challenges: throughout the year with two consecutive quarters of gross margini improvements and four consecutive • Competing business strategies: While we had begun quarters of operating expenseii improvements. Pro forma the process of licensing our Palm OS software to hand- gross margini grew from a low of 20% in Q2 FY ‘02 to held manufacturers to expand the Palm Economy, the 35% in Q4 FY ‘02, while pro forma operating expensesii perceived lack of independence and the opportunistic have declined by 36% from the end of Q4 FY ’01 to nature of our licensing activities limited the potential of the end of Q4 FY ’02. both our Palm Solutions business and our Palm OS software business and blurred the focus and clarity of We made the strategic decision to commit ourselves fully purpose of each; to the operating system software licensing business. This decision was anchored in the fundamental belief that • Operational problems: We needed to improve supply handheld devices will become part of our daily life, much chain management and product development. -

The Great Telecom Meltdown

4 The Internet Boom and the Limits to Growth Nothing says “meltdown” quite like “Internet.” For although the boom and crash cycle had many things feeding it, the Internet was at its heart. The Internet created demand for telecommunications; along the way, it helped create an expectation of demand that did not materialize. The Internet’s commercializa- tion and rapid growth led to a supply of “dotcom” vendors; that led to an expec- tation of customers that did not materialize. But the Internet itself was not at fault. The Internet, after all, was not one thing at all; as its name implies, it was a concatenation [1] of networks, under separate ownership, connected by an understanding that each was more valuable because it was able to connect to the others. That value was not reduced by the mere fact that many people overesti- mated it. The ARPAnet Was a Seminal Research Network The origins of the Internet are usually traced to the ARPAnet, an experimental network created by the Advanced Research Projects Agency, a unit of the U.S. Department of Defense, in conjunction with academic and commercial contrac- tors. The ARPAnet began as a small research project in the 1960s. It was pio- neering packet-switching technology, the sending of blocks of data between computers. The telephone network was well established and improving rapidly, though by today’s standards it was rather primitive—digital transmission and switching were yet to come. But the telephone network was not well suited to the bursty nature of data. 57 58 The Great Telecom Meltdown A number of individuals and companies played a crucial role in the ARPAnet’s early days [2]. -

Mispricing in Tech Stock Carve-Outs Author(S): Owen A

Can the Market Add and Subtract? Mispricing in Tech Stock Carve-Outs Author(s): Owen A. Lamont and Richard H. Thaler Source: The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 111, No. 2 (Apr., 2003), pp. 227-268 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3555203 Accessed: 08/01/2010 15:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Political Economy.