Volume 311, No. 1 Opinions Filed in January-March 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disciples How the Early Church Made Disciples

NEWS: GC15 Worship │ Winona Lake │ Backpacks of Food LIGHTLIGHTANDLIFEMAGAZINE.COM+ LIFE │ JULY 2015 MAKE DISCIPLES HOW THE EARLY CHURCH MADE DISCIPLES DIETS AND DISCIPLESHIP JOHN WESLEY’S GENERAL RULES OPEN OUR EYES LEARN HOW TO PARTNER STRONG OPENERS BY JEFF FINLEY JULY 2015 │ Whole No. 5277, Volume 148, No. 7 MANAGING EDITOR, Jeff Finley LEAD DESIGNER, Erin Eckberg COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR, Jay Cordova COPY EDITOR, Dawn McIlvain Stahl CONTENT STRATEGIST, Mark Crawford DISCIPLE OR CIRCULATION MANAGER, Katie Ehle BUSINESS SALES ASSOCIATE, Marvin Gray WEB ARCHITECT, Douglas Britt DECLINE DESIGNER, Kelly Holt he church in the United States is having FOCUS GROUP: a rough time of it lately, according to the Raisa Fabre Jason Roberts news media and pollsters. David Kendall J.R. Rushik Rob McKenna Denny Wayman TRecent headlines include “Big Drop in Share of Jason Morriss Trisha Welstad Americans Calling Themselves Christian” (New B. Elliott Renfroe York Times), “Millennials Leaving Church in JEFF FINLEY SPANISH TRANSLATION: Managing Editor Droves” (CNN), “Christians in U.S. on Decline as COORDINATOR, Rodrigo Lozano Number of ‘Nones’ Grows” (NPR) and “America Is Ezequiel Alvarez Alma Jasinski Jazmin Angulo Karen Kabandama Losing Its (Christian) Religion” (The Week). Fredy Caballero Esther Ortiz The headlines resulted from a Pew Research Carmen Hosea Center survey, “America’s Changing Religious WEBSITE: lightandlifemagazine.com Landscape” (fmchr.ch/pewacrl), that found EMAIL US: [email protected] NEWS AND SUBMISSIONS: [email protected] “between 2007 and 2014, the Christian share of ADVERTISING: [email protected] the population fell from 78.4% to 70.6 %.” ADDRESS ALL CORRESPONDENCE TO: The church isn’t just struggling to win new Light + Life Magazine, 770 N. -

CAT CRAZY, TRI FI and Other Multihull Comparisons by Jim Brown

CAT CRAZY, TRI FI And Other Multihull Comparisons By Jim Brown “There is nothing, absolutely nothing, quite so much worth doing as simply messing about in…” Multihulls! That paraphrased quote is pilfered for the most part from Ratty, the revered rodent in Kenneth Grahame’s venerated tale “The Wind in the Willows.” Of course, Grahame and Ratty said it of ordinary boats, and neither would have, even could have, said it of multihulls. But if Brown had been the author instead of Grahame, his character Ratty might have said something like, “There is nothing, absolutely nothing quite so creative as screwing around with multihulls.” By “screwing around,” Ratty would have spoken literally, meaning to conceive, gestate, whelp, wean and release upon the Earth’s fluid interface one’s very own flesh and blood multihulls. And that’, impatient reader, is what this appendix is about, so like most appendices reading it is strictly optional. In that you are reading on, please be prepared for some sacrilege. Suggesting there is something divine about boat design and construction I will try to trace multihull origins by expanding on the theorem expressed by my late friend Walt Glaser who said (in Chapter 1 of my memoir, “Among the Multihulls,”), “A man builds a boat to make up for the fact that he can’t build a baby… What else can a guy produce with his own body that so closely simulates a living thing?” It took me many years of both messing about in and screwing around with boats to apprehend this aspect of watercraft, and I admit that it still takes quite a stretch for me to accept the notion. -

Fitting the Unstayed Mast Rig To

ITTING THE UNSTAYED MAST RIG TO YOUR BOAT SOME POPULAR QUESTIONS ANSWERED: - . Will it suit any boat of any hull shape? - Yes, and will particularly aid shallow draft hulls of low ballast ratio as the flexibility of the mast reduces heeling in all conditions. 2. Can it be fitted to multihulls? - Yes, Trimaran installations are similar to monohulls. Catamarans can either have modified bridge decks to obtain sufficient bury of mast or fit a smaller mast in each hull. 3. Can I use my existing stayed rig mast?- No, with the exception of some solid timber Gaff rig masts. 4. Does the mast have to be keel stepped? - Preferably, but it can be fitted in a deck tabernacle. 5. Where is the mast stepped? - Approximately 2 to 4 feet forward of a stayed mast postion. 6. Does it have to be near a bulkhead? - No, as the load transmitted to the deck is not enormous. 7. What structural modifications will I have to make to my boat? - Probably increase the deck strength at the mast by adding:- - for GRP boats more layup of C.S. matt which will be hidden by the head lining under the deck. - for steel, alloy, ferrocement, timber boats, add a deck beam. The mast step only needs to be firmly secured to the keel and no extra reinforcement is necessary to be the boat's keel. - for sheeting to the pushpit, possibly, add a bracing strut across the existing tube, such as a sheet track. 8. How many sails and of what area should be used? - As a general rule:- For boats up to 30 ft., one sail is more ideal. -

An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo: a Vessel from the Junk Trade

An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo: A Vessel from the Junk Trade Explorations in Southeast Asian Studies A Journal of the Southeast Asian Studies Student Association Vol 1, No. 2 Fall 1997 Contents Article 1 Article 2 Article 3 Article 4 Article 5 Article 6 Article 7 Article 8 An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo A Vessel from the Junk Trade Hans Van Tilburg Hans Van Tilberg is a Ph.D. candidate in History and instructor of the maritime archaeology field school at the University of Hawai'i, Manoa. His research interests have focused on maritime history and underwater archaeology in Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. Notes The topic of Chinese shipping to and from Southeast Asia has fascinated me for quite a while now. One of the reasons I find it so interesting is that it's such a difficult subject to research. One of the main problems seems to be that many aspects of the private commercial sea-going trade simply went unrecorded. Often only the barest information of "size of ship" and "number of crew" was ever committed to register, while the efforts of ship construction, fitting out, manning, and the details of the actual voyages, remained known only at the village or family level. And as has been noted by many observers, officially the Chinese government had very little interest in the activities of those Chinese who went abroad, those who were foolish enough to want to travel so many miles away from home. Yet the influence of what is commonly known as the Junk Trade, especially in the eighteeth and nineteenth centuries, is no small subject. -

October 2016

October 2016 MULTIHULL YACHT CLUB QUEENSLAND: PO BOX 178, WYNNUM. Q. 4178 Volume 50 Number 18 Vodafone Frank Racing - New Race Record Holder of the Groupama New Caledonia Race Photo Patrice Morin 02 Sydney Brisbane Geelong Perth Geelong Brisbane Sydney - 9939 - 2273 07 2273 - 3203 - 1330 03 - 5222 - 2930 082930 - 9331 - 3910 3910 At the club house, Northern Arm of GENERAL Manly Harbour (Trafalgar St) MEETING 7:30PM Thursday 6th October Guest Speaker: Craig Margetts 2 Monthly Events 8-9th October St Helena Cup 15-16th October Spring Series Passage Series Combined Clubs Races 13 & 14 23rd October Triangles 29th-30th October Mooloolaba Weekend Commodore’s Comment By Bruce Wieland SPRING SERIES The new MYCQ Spring Series kicks off this coming weekend. The first leg is the St Helena Cup, followed by two very innovative courses the following weekend featuring optional simultaneous starts at either north or south of the river. The northern and southern courses overlap so both fleets will cross paths several times. The concept of these courses is the brainchild of Past Commodore Richard Jenkins and promises to be a lot of fun. The final weekend of the Spring Series will include the MCC triangles on Sunday the 23rd October. For the cruisers, THERE ARE SHORTENED COURSES, so find a crew and come sailing with the race fleet! OMR VIDEO The edited video of the OMR Review Committee information meeting is finally completed and is now available on the MYCQ website. Thanks to Sean for capturing the essence of the meeting, but a big thanks also to the OMR Committee members Alasdair Noble, Mike Hodges and Geoff Cruse for their easily understood presentation detailing the amendments to the OMR Rule. -

* Omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1

* omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1 dutch ships in tropical waters robert parthesius The end of the 16th century saw Dutch expansion in Asia, as the Dutch East India Company (the VOC) was fast becoming an Asian power, both political and economic. By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen. This landmark study looks at perhaps the most important tool in the Company’ trading – its ships. In order to reconstruct the complete shipping activities of the VOC, the author created a unique database of the ships’ movements, including frigates and other, hitherto ignored, smaller vessels. Parthesius’s research into the routes and the types of ships in the service of the VOC proves that it was precisely the wide range of types and sizes of vessels that gave the Company the ability to sail – and continue its profitable trade – the year round. Furthermore, it appears that the VOC commanded at least twice the number of ships than earlier historians have ascertained. Combining the best of maritime and social history, this book will change our understanding of the commercial dynamics of the most successful economic organization of the period. robert parthesius Robert Parthesius is a naval historian and director of the Centre for International Heritage Activities in Leiden. dutch ships in amsterdam tropical waters studies in the dutch golden age The Development of 978 90 5356 517 9 the Dutch East India Company (voc) Amsterdam University Press Shipping Network in Asia www.aup.nl dissertation 1595-1660 Amsterdam University Press Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters The development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) shipping network in Asia - Robert Parthesius Founded in as part of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the Amsterdam Centre for the Study of the Golden Age (Amsterdams Centrum voor de Studie van de Gouden Eeuw) aims to promote the history and culture of the Dutch Republic during the ‘long’ seventeenth century (c. -

Lu Statement2 REDACTED

Alice Lu 4/8/16 ANTHRO 1218 Building a Quick, Navigable Ship to Evade Enemies in the First Opium War Previously, you followed me on a journey to identify this ship model. Now, we are going to take what we learned about its role in the First Opium War to examine specific elements of ship construction. Knowing this Chinese junk fought in the First Opium War, we can extrapolate information about where it was built, how it was constructed based on the region, and if these construction techniques were effective. Since these junks fought in the First Opium War, they must have met requirements in order to be operational in naval warfare; as seen by various elements of this model’s construction, including hull shape, navigation, and propulsion systems, this ship was built to be strong, stable, and easily maneuverable, giving it an advantage in traditional oceanic warfare. From geographic information on the First Opium War as well as the shape and elements of the hull, we can categorize this vessel as a southeastern type of Chinese junk (either a fuchuan or guanchuan), which were known for their stability in rough seas. The fuchuan and guanchuan were both named after the region where it is built, the Fujian and Guandong provinces of southeastern China (Green, 2), where much of the First Opium War was fought (Figure 1). These ships were built for speed and navigating rough waters (Qiupeng, 496). This ship model has a long gu or keel timber painted red, running along the length of the boat; it also has a V-shaped hull, which matches descriptions of both a fuchuan and a guanchuan (Ward, 29-30; Davies, 207; Chen, 1; Green, 2) (Figure 2). -

Ronan Shortpaper

A Chinese War Junk of the Opium War Era John Henry Ronan, Jr. ANTHRO 1218 Artifact number 99-12-60/52938 sits in the storage of the Peabody Museum, listed only as “War Boat”. The ship model, roughly 2 feet long and a foot and a half high, features unique and prominent sails. These sails, known as Chinese lugsails or junk rigs, have timbers called battens running across their entire width. The battens give the sails a sturdy appearance, and make the sails easy to control in changing trade winds. Wicker shields also run along the port and starboard sides of the deck and a wicker canopy covers the ship’s stern. It is interesting to note that the wicker shields coexist with a breech loading cannon on the starboard side, as well as edged weapons at stern. The wicker shields would seemingly serve little use up against a cannon, and it is hard to believe that the two can coexist on a ship of the same era. The final initial observation is the unique deep keel and rudder, both of which have diamond shaped holes all along them. Taken together, these observations point to the ship being a Chinese Junk, and the heavy armaments on board (and the artifact’s title) point to the ship being a War Junk. Digging a little deeper, we can conclude that this ship model is likely an 1840 Chinese War Junk, like those that would have been used in the First Opium War (1839-1842). In many ways this ship model is representative of China in the mid 19th century, a country mired in antiquated traditions facing a growingly belligerent and technological advanced world. -

A Description of the Chinese Junk, “Keying.”

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 0,5 ,Tl'mI‘PL‘II ; awn‘ '"HIxqmnnflm‘xvii-Quincy; w"1“mifiwugEEMmmIHWm.‘ ‘ V ‘ 77,‘; a i‘‘ 2.; i _ } V MW4'‘ ’ L "'H‘ {HM ‘, A , , ‘1 v‘ ‘ ‘3 ‘ t , ‘a i i t L‘ ‘H ‘ xx?‘ \ m : THEKEYING. .‘ / ‘1.". M wt‘ ’ \ H. 1} ' ‘ ~ . / Ah I A DESCRIPTION CHINESE JUNK, , “IKEYIENQ.” /< ii " FOURTH ED'ITION. ‘3c “WW .1» PRINTED FOR THE PROPRIETORS OF THE (.1 JUNK, AND SOLD ONLY ON BOARD. LONDON, 1848. m) M0 y' g J. SUCH, Printer, 29, Budge Row, Watling street, City. DESCRIPTION OF THE KEYING. E may venture to say, that, if any person had i been bold enough, three years since, to have ‘ predicted that we should have had, within the ‘ walls of the East India Docks, a Chinese Junk, ‘ ‘ with her crew and rigging, the predicter would ‘ have been thought a visionary. And yet here is ' one, open to our inspection, after having passed / over, in its voyage from the Celestial Empire to our own, a course equal in length to the entire circuit of the globe. Not very long since, there was exhib ited, near Hyde Park, a most interesting and valuable collection of Chinese curiosities. These, however, were things which could be put into packing cases, and transported, with comparative facility, from one part of the world to another : the difliculty of bringing them to England depended more upon the proprietors’ means than upon anything else. -

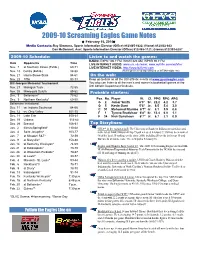

2009-10 Screaming Eagles Game Notes

2009-10 Screaming Eagles Game Notes ♦ February 15, 2010♦ Media Contacts: Ray Simmons, Sports Information Director (Office) 812/465-1622; (Home) 812/402-643 Dan McDonnell, Asst. Sports Information Director (Office) 812/465-1121; (Home) 812/303-6287 2009-10 Schedule: Listen to and watch the games: RADIO: ESPN 106.7 FM; WSWI 820 AM; WPSR 90.7 FM Date Opponents Time LIVE INTERNET AUDIO: www.usi.edu/wswi; www.wyfxfm.com/wyfxfm/ Nov. 7 at Southern Illinois (Exhib.) 69-71 LIVE INTERNET VIDEO: http://www.b2livetv.com Nov. 13 Centre (Exhib.) 88-58 (Home games aired tape-delayed on WTSN-Insight 186) Nov. 21 Harris-Stowe State 84-61 On the web: Nov. 23 Tiffin 93-73 Keep up-to-date on all the USI athletic events at www.gousieagles.com. BIll Joergen Memorial Tournament You also can listen to all the men’s and women’s basketball games at the USI Athletic Department Web site. Nov. 27 Michigan Tech 72-55 Nov. 28 Minnesota Duluth 89-52 Probable starters: Dec. 3 Bellarmine* 75-62 Pos. No. Player Ht. Cl. PPG RPG APG Dec. 5 Northern Kentucky* 69-50 Bellarmine Invitational G 2 Jamar Smith 6’3” Sr. 22.2 4.2 3.7 G 5 Kevin Gant 5’8” Jr. 6.5 5.4 3.0 Dec. 11 vs. Indiana Southeast 84-68 C 51 Mohamed Ntumba 6’7” Jr. 8.1 5.9 0.6 Dec. 12 vs. Ohio Valley 101-35 F 1 Tyrone Bradshaw 6’8” Sr. 13.4 6.0 1.1 Dec. 14 Lake Erie 105-64 F 34 Nick Duncheon 6’7” Jr. -

February2021

February 2021 Sponsored by Kraken Yachts February 2021 From The Pulpit This issue Ocean Sailor February 2021 Readers Questions By Dick Beaumont - Chairman of Kraken Yachts Page two Feature Containers Thanks to the restrictions imposed on us all A lot of people here are complaining Page Three by the virus I can’t say we’ve exactly hit the about the privations this different way deck running in 2021, but we have been as of living has imposed on us, and while busy as ever with Kraken Yachts and Ocean it’s frustrating, I think the pandemic has Technical & Equipment Sailor Magazine. taught us we must simply learn to enjoy The 8th Commandment different and simpler things for a while and Dick Durham and I put out our first Ocean be thankful that perhaps we might live to Page eight Sailor Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google fight another day. I’m sure many people Podcasts, Amazon Music, Spotify and have realized that the freedoms we had Sailing Skills we’ve been delighted with the feedback taken for granted before all this should be and positive support we’ve received to cherished. We must use our time to better Man Overboard date. We’ve had hundreds of listeners just effect when the maelstrom caused by this Page twelve in the first few days. Support from the plague does eventually pass, as the world’s listeners is vital for the podcast’s success, population becomes vaccinated and herd so please check it out and give us a review immunity spreads. Sailors' Stories and a 5-star rating. -

Small Fishing Craf

MECHANIZATION SMALL FISHING CRAF Outboards Inboard Enginc'In Open Craft Inboard Engines in Decked Cra t Servicing and Maintenance Coca ogo Subjects treated in the various sections are: Installation and operation of outboard motors; Inboard engines in open craft; Inboard engines in decked craft; Service and maintenance. Much of the editorial matter is based upon the valuable and authoritative papers presented at a symposium held in Korea and )rganized by the FAO and the Indo- ' acific Council. These papers St.1.07,0,0 MV4,104,4",,,A1M, ; have been edited by Commander John Burgess, and are accom- oanied by much other material of value from various authors. Foreword by Dr. D. B. Finn, C.14.G. Director, Fisheries Division, FAO t has become a tradition for the three sections of FAO's Fisheries Technology BranchBoats, Gear and Processingalternately, in each biennium, to organize a large technical meeting with the participation of both Government institutes and private industry. It all started in 1953 with the Fishing Boat Congress having sessions in Paris and Miami, the proceedings of which were published in " Fishing Boats of the World." A Processing Meeting followed in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in 1956, and a ,ear Congress was organized in Hamburg, Germany, in 1957. A second Fishing Boat Congress was held in Rome in 1959, the proceedings of which were again published in " Fishing Boats of the World :2." Those two fishing boat congresses were, in a way, rather comprehensive, trying to cover the whole field of fishing boat design and also attracting participants from dzfferent backgrounds. This was not a disadvantage, because people having dzfferent experiences were mutually influencing each other and were induced to see further away than their own limited world.