NOTES Notes to Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janakeeya Hotel Updation 07.09.2020

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. of Sl. Rural / No Of Parcel By Sponsored by District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Initiative Delivery units No. Urban Members Unit LSGI's (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th) Janakeeya 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 32 0 0 Hotel Coir Machine Manufacturing Janakeeya 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Urban 4 194 0 15 Company Hotel Janakeeya 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 137 220 0 Hotel Janakeeya 4 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 0 60 5 Hotel Janakeeya 5 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 112 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 6 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 63 12 10 Hotel Janakeeya 7 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 73 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 8 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 10 0 0 Hotel chengannur market building Janakeeya 9 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM Urban 5 70 0 0 complex Hotel Chennam pallipuram Janakeeya 10 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Rural 3 0 55 0 panchayath Hotel Janakeeya 11 Alappuzha Cheppad Sreebhadra catering unit Choondupalaka junction Rural 3 63 0 0 Hotel Near GOLDEN PALACE Janakeeya 12 Alappuzha Cheriyanad DARSANA Rural 5 110 0 0 AUDITORIUM Hotel Janakeeya 13 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality NULM canteen Cherthala Municipality Urban 5 90 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 14 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality Santwanam Ward 10 Urban 5 212 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 15 Alappuzha Cherthala South Kashinandana Cherthala S Rural 10 18 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 16 Alappuzha Chingoli souhridam unit karthikappally l p school Rural 3 163 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 17 Alappuzha Chunakkara Vanitha Canteen Chunakkara Rural 3 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 18 Alappuzha Ezhupunna Neethipeedam Eramalloor Rural 8 0 0 4 Hotel Janakeeya 19 Alappuzha Harippad Swad A private Hotel's Kitchen Urban 4 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 20 Alappuzha Kainakary Sivakashi Near Panchayath Rural 5 0 0 0 Hotel 43 LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. -

M. R Ry. K. R. Krishna Menon, Avargal, Retired Sub-Judge, Walluvanad Taluk

MARUMAKKATHAYAM MARRIAGE COMMISSION. ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES BY M. R RY. K. R. KRISHNA MENON, AVARGAL, RETIRED SUB-JUDGE, WALLUVANAD TALUK. 1. Amongst Nayars and other high caste people, a man of the higher divi sion can have Sambandham with a woman of a lower division. 2, 3, 4 and 5. According to the original institutes of Malabar, Nayars are divided into 18 sects, between whom, except in the last 2, intermarriage was per missible ; and this custom is still found to exist, to a certain extent, both in Travan core and Cochin, This rule has however been varied by custom in British Mala bar, in Avhich a woman of a higher sect is not now permitted to form Sambandham with a man of a lower one. This however will not justify her total excommuni cation from her caste in a religious point of view, but will subject her to some social disabilities, which can be removed by her abandoning the sambandham, and paying a certain fine to the Enangans, or caste-people. The disabilities are the non-invitation of her to feasts and other social gatherings. But she cannot be prevented from entering the pagoda, from bathing in the tank, or touch ing the well &c. A Sambandham originally bad, cannot be validated by a Prayaschitham. In fact, Prayaschitham implies the expiation of sin, which can be incurred only by the violation of a religious rule. Here the rule violated is purely a social one, and not a religious one, and consequently Prayaschitham is altogether out of the place. The restriction is purely the creature of class pride, and this has been carried to such an extent as to pre vent the Sambandham of a woman with a man of her own class, among certain aristocratic families. -

Requiring Body SIA Unit

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY FINAL REPORT LAND ACQUISITION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF OIL DEPOT &APPROACH ROAD FOR HPCL/BPCL AT PAYYANUR VILLAGE IN KANNUR DISTRICT 15th JANUARY 2019 Requiring Body SIA Unit RAJAGIRI outREACH HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM Rajagiri College of Social Sciences CORPORATION LTD. Rajagiri P.O, Kalamassery SOUTHZONE Pin: 683104 Phone no: 0484-2550785, 2911332 www.rajagiri.edu 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Project and Public Purpose 1.2 Location 1.3 Size and Attributes of Land Acquisition 1.4 Alternatives Considered 1.5 Social Impacts 1.6. Mitigation Measures CHAPTER 2 DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1. Background of the Project including Developers background 2.2. Rationale for the Project 2.3. Details of Project –Size, Location, Production Targets, Costs and Risks 2.4. Examination of Alternatives 2.5. Phases of the Project Construction 2.6.Core Design Features and Size and Type of Facilities 2.7. Need for Ancillary Infrastructural Facilities 2.8.Work force requirements 2.9. Details of Studies Conducted Earlier 2.10 Applicable Legislations and Policies CHAPTER 3 TEAM COMPOSITION, STUDY APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3.1 Details of the Study Team 3.2 Methodology and Tools Used 3.3 Sampling Methodology Used 3.4. Schedule of Consultations with Key Stakeholders 3.5. Limitation of the Study CHAPTER 4 LAND ASSESSMENT 4.1 Entire area of impact under the influence of the project 4.2 Total Land Requirement for the Project 4.3 Present use of any Public Utilized land in the Vicinity of the Project Area 2 4.4 Land Already Purchased, Alienated, Leased and Intended use for Each Plot of Land 4.5. -

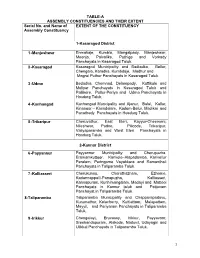

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

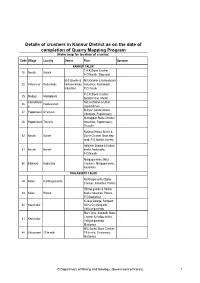

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O. -

Name of District : KASARAGOD Phone Numbers LAC NO

Name of District : KASARAGOD Phone Numbers LAC NO. & PS Name of BLO in Name of Polling Station Designation Office address Contact Address Name No. charge office Residence Mobile "Abhayam", Kollampara P.O., Nileshwar (VIA), K.Venugopalan L.D.C Manjeshwar Block Panchayath 04998272673 9446652751 1 Manjeswar 1 Govt. Higher Secondary School Kunjathur (Northern Kasaragod District "Abhayam", Kollampara P.O., Nileshwar (VIA), K.Venugopalan L.D.C Manjeshwar Block Panchayath 04998272673 9446652752 1 Manjeswar 2 Govt. Higher Secondary School Kunjathur (Northern Kasaragod District N Ishwara A.V.A. Village Office Kunjathur 1 Manjeswar 3 Govt. Lower Primary School Kanwatheerthapadvu, Kun M.Subair L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Melethil House, Kodakkad P.O. 04998272673 9037738349 1 Manjeswar 4 Govt. Lower Primary School, Kunjathur (Northern S M.Subair L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Melethil House, Kodakkad P.O. 04998272673 9037738349 1 Manjeswar 5 Govt. Lower Primary School, Kunjathur (Southern Re Survey Superintendent Office Radhakrishnan B L.D.C. Ram Kunja, Near S.G.T. High School, Manjeshwar 9895045246 1 Manjeswar 6 Udyavara Bhagavathi A L P School Kanwatheertha Manjeshwar Arummal House, Trichambaram, Taliparamba P.O., Rajeevan K.C., U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath 04998272238 9605997928 1 Manjeswar 7 Govt. Muslim Lower Primary School Udyavarathotta Kannur Prashanth K U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath Udinur P.O., Udinur 04998272238 9495671349 1 Manjeswar 8 Govt. Upper Primary School Udyavaragudde (Eastern Prashanth K U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath Udinur P.O., Udinur 04998272238 9495671349 1 Manjeswar 9 Govt. Upper Primary School Udyavaragudde (Western Premkumar M L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Meethalveedu, P.O.Keekan, Via Pallikere 04998 272673 995615536 1 Manjeswar 10 Govt. -

The Chirakkal Dynasty: Readings Through History

THE CHIRAKKAL DYNASTY: READINGS THROUGH HISTORY Kolathunadu is regarded as one of the old political dynasties in India and was ruled by the Kolathiris. The Mushaka vamsam and the kings were regarded as the ancestors of the Kolathiris. It was mentioned in the Mooshika Vamsa (1980) that the boundary of Mooshaka kingdom was from the North of Mangalapuram – Puthupattanam to the Southern boundary of Korappuzha in Kerala. In the long Sanskrit historical poem Mooshaka Vamsam, the dynastic name of the chieftains of north Malabar (Puzhinad) used is Mooshaka (Aiyappan, 1982). In the beginning of the fifth Century A.D., the kingdom of Ezhimala had risen to political prominence in north Kerala under Nannan… With the death of Nannan ended the most glorious period in the history of the Ezhimala Kingdom… a separate line of rulers known as the Mooshaka kings held sway over this area 36 (Kolathunad) with their capital near Mount Eli. It is not clear whether this line of rulers who are celebrated in the Mooshaka vamsa were subordinate to the Chera rulers of Mahodayapuram or whether they ruled as an independent line of kings on their own right (in Menon, 1972). The narration of the Mooshaka Kingdom up to the 12th Century A.D. is mentioned in the Mooshaka vamsa. This is a kavya (poem) composed by Atula, who was the court poet of the King Srikantha of Mooshaka vamsa. By the 14th Century the old Mooshaka kingdom had come to be known as Kolathunad and a new line of rulers known as the Kolathiris (the ‘Colastri’ of European writers) had come into prominence in north Kerala. -

KNSS Cover December 2017

knSS news bulletin December 2017 Contents Editorial ...................................................01 ditorial From the Chairman’s Desk .....................02 a¶w Pb-´n, ]pXp-h-Õ-cw,E \½psS 8þmw hmfyw From the Gen. Secretary .........................03 KNSS Karayogam News .........................06 2018 P\p-hcn 2 \v kap-Zm-bm-Nm-cy³ {io a¶¯v ]ß-\m-`sâ 141þmw Mahila Vibhag News ................................19 P·-Zn-\-am-WtÃm! Youth Wing News ....................................29 hnhn[ \mbÀ hn`m-K-§sf Iq«n-bn-W-¡n, kulmÀ±-am-Wv, aÕ-c-aà Sahithya Vedi ...........................................30 kap-Zm-tbm-¶-a-\-¯nsâ D¯a amÀ¤-sa¶v AwK-§sf t_m[-hm- MMECT News ...........................................35 ·m-cm-¡n, IÀ½-[o-c-cm¡n am-än-sb-Sp¯ At±-l-¯nsâ alm-{]-Xn- Benevolent Fund News ..........................37 `-sbbpw ISp¯ \nÝbZmÀVy-s¯bpw GsXmcp kap-Zmb kvt\ Kayikavedi ................................................38 lnbpw, a¶w Pb´n thf-bn {]tXy-In-¨pw, HmÀt¡-ï-Xm-Wv. At±- Vivahakendra ...........................................39 l-¯nsâ Im¸m-Sp-IÄ XpSÀ¶v \ap-s¡Ãmw tkh-\-\n-c-X-cm-hmw. XpS-¡-¯nse 'challenges'Dw C¶s¯ 'challenges'Dw Ime-¯n-\-\p- List of Advertisers Dr. V.S. Ramakrishnan Nair ......................6 k-cn¨v hyXy-kvX-am-sW-¦n-epw, kap-Zm-tbm-¶-a-\-¯n\v \ap-¡-hsb 'Solutions' Sree Ayyappa Catering Service ...............9 t\cn-tSïXv, Isï-t¯-ïXv Ime-¯nsâ Bh-iy-am- C.D. Premlal .............................................10 Wv. shÃp-hn-fn-Isf Hä-s¡-«mbn \n¶v \ap¡v t\cn-Smw, hnP-bn¡mw! Vasudevan Naboothiri ............................11 GhÀ¡pw a¶w-P-b´n Biw-k-IÄ. Ic-tbm-K-§-fnepw t_mÀUnepw V.P. -

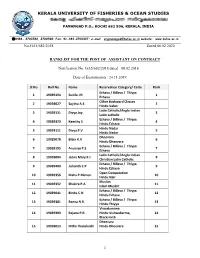

Ranklist for the Post of Assistant on Contract

KERALA UNIVERSITY OF FISHERIES & OCEAN STUDIES PANANGAD P.O., KOCHI 682 506, KERALA, INDIA 0484- 2703782, 2700598; Fax: 91-484-2700337; e-mail: [email protected] website: www.kufos.ac.in No.GA5/682/2018 Dated,06.02.2020 RANKLIST FOR THE POST OF ASSISTANT ON CONTRACT Notification No. GA5/682/2018 dated 08.02.2018 Date of Examination : 24.11.2019 Sl No Roll No Name Reservation Category/ Caste Rank Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 1 19039194 Sunila .M 1 Ezhava Other Backward Classes 2 19039027 Sajitha A.S 2 Hindu Valan Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 3 19039131 Divya Joy 3 Latin catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 4 19039323 Keerthy S 4 Hindu Ezhava Hindu Nadar 5 19039111 Divya P.V 5 Hindu Nadar Dheevara 6 19039078 Bibin K.V 6 Hindu Dheevara Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 7 19039195 Anusree P.S 7 Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 8 19039084 Jeena Mary K J 8 Christian Latin Catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 9 19039403 Jishanth C.P 9 Hindu Ezhava Open Competetion 10 19039356 Nisha P.Menon 10 Hindu Nair Muslim 11 19039352 Shakira P.A. 11 Islam Muslim Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 12 19039041 Bindu.C.N 12 HIndu Ezhava Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 13 19039381 Beena N.K. 13 Hindu Thiyya Viswakarama 14 19039383 Rejana P.R. Hindu Vishwakarma, 14 Blacksmith Dheevara 15 19039013 Hitha Thanckachi Hindu Dheevara 15 1 16 Amrutha Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 16 19039336 Sundaram Hindu Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 17 19039114 Mary Ashritha 17 Latin Catholic Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 18 19039120 Basil Antony K.J 18 Latin Catholic Dheevara 19 19039166 Thushara M.V 19 Deevara Sreelakshmi K Open Competetion 20 19039329 20 Nair Nair Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 21 19039373 Dileep P.R. -

Introduction

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723 Mailaparambil, J.B. Citation Mailaparambil, J. B. (2007, December 12). The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). INTRODUCTION Cultural apartheid was the dominant ideal in medieval Muslim India...1 This is a study about the Arackal Ali Rajas of Cannanore, the most prominent maritime merchants in pre-colonial Kerala and one of the very few early-modern Indian maritime merchant groups who succeeded in carving out a powerful political configuration of their own. The extensive maritime network of the Arackal House was based at the port-town of Cannanore. From that place, this Mappila Muslim family came to dominate the commercial networks of various other Mappila families in Cannanore as well as in its various satellite ports such as Maday, Baliapatanam, Dharmapatanam and Nileswaram.2 Before setting out to expound my own analytical starting position, let me begin by briefly introducing the spatial and temporal co-ordinates of this study as well as the sources and historiographical antecedents on which it is based. Kolathunadu, 1663-1723 The ‘kingdom of Cannanore’ or Kolathunadu constitutes roughly what is now called the Cannanore District of Kerala State in the Republic of India. -

Chapter Iv Traces of Historical Facts From

CHAPTER IV TRACES OF HISTORICAL FACTS FROM SANDESAKAVYAS & SHORT POEMS Sandesakavyas occupy an eminent place among the lyrics in Sanskrit literature. Though Valmiki paved the way in the initial stage it was Kalidasa who developed it into a perfect form of poetic literature. Meghasandesa, the unique work of Kalidasa, was re- ceived with such enthusiasam that attempts were made to emulate it all over India. As result there arose a significant branch of lyric literature in Sanskrit. Kerala it perhaps the only region which produced numerous works of real merit in this field. The literature of Kerala is full of poems of the Sandesa type. Literature can be made use of to yield information about the social history of a land and is often one of the main sources for reconstructing the ancient social customs and manners of the respective periods. History as a separate study has not been seriously treated in Sanskrit literature. Apart form literary merits, the Sanskrit literature of Kerala contains several historical accounts of the country with the exception of a few historical Kavyas, it is the Sandesakavyas that give us some historical details. Among the Sanskrit works, the Sandesa Kavya branch stands in a better position in this field (matter)Since it contains a good deal of historical materials through the description of the routes to be followed by the messengers in the Sandesakavyas. The Sandesakavyas play an impor- tant role in depicting the social history of their ages. The keralate Sandesakavyas are noteworthy because of the geographical, historical, social and cultural information they supply about the land. -

THE GEO-POLITICAL SETTING of KOLATHUNADU Regional History

9 CHAPTER ONE THE GEO-POLITICAL SETTING OF KOLATHUNADU Since every historical event occurs both in space as well as in time, history cannot, except in some of its more specialised branches, be dissociated from country or place…Since history must concern itself with the location of the events, which it investigates, it must continually raise, not only the familiar questions Why? and Why then? but also the questions Where and Why there?1 Regional history in early-modern Kerala is a rarely visited field of research.2 Two large stumbling blocks are the unavailability of and limit- ed accessibility to source materials from which to construe comprehensive regional histories of this period. Moreover, the general postulation that pre-colonial Kerala followed an even pattern of historical development throughout the centuries seems to tempt the researcher to pass over any regional variations as minor ‘deviations’ from the general pattern of devel- opment. Furthermore, at first glance the region cannot boast of being the seat of an imposing political formation in comparison with those of the other regions of South India in general and Kerala in particular. The neglect of the northernmost part of Kerala in the general historiography of the region might perhaps be attributed to these reasons. Out of the numerous principalities (nadus) which emerged in Kerala during the medieval period, Kolathunadu stands out as a region of partic- ular historical interest because of its unique pattern of socio-political development. The distinctive geographical features of the region had an important role in shaping the socio-political culture of Kolathunadu.