THE GEO-POLITICAL SETTING of KOLATHUNADU Regional History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Requiring Body SIA Unit

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY FINAL REPORT LAND ACQUISITION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF OIL DEPOT &APPROACH ROAD FOR HPCL/BPCL AT PAYYANUR VILLAGE IN KANNUR DISTRICT 15th JANUARY 2019 Requiring Body SIA Unit RAJAGIRI outREACH HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM Rajagiri College of Social Sciences CORPORATION LTD. Rajagiri P.O, Kalamassery SOUTHZONE Pin: 683104 Phone no: 0484-2550785, 2911332 www.rajagiri.edu 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Project and Public Purpose 1.2 Location 1.3 Size and Attributes of Land Acquisition 1.4 Alternatives Considered 1.5 Social Impacts 1.6. Mitigation Measures CHAPTER 2 DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1. Background of the Project including Developers background 2.2. Rationale for the Project 2.3. Details of Project –Size, Location, Production Targets, Costs and Risks 2.4. Examination of Alternatives 2.5. Phases of the Project Construction 2.6.Core Design Features and Size and Type of Facilities 2.7. Need for Ancillary Infrastructural Facilities 2.8.Work force requirements 2.9. Details of Studies Conducted Earlier 2.10 Applicable Legislations and Policies CHAPTER 3 TEAM COMPOSITION, STUDY APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3.1 Details of the Study Team 3.2 Methodology and Tools Used 3.3 Sampling Methodology Used 3.4. Schedule of Consultations with Key Stakeholders 3.5. Limitation of the Study CHAPTER 4 LAND ASSESSMENT 4.1 Entire area of impact under the influence of the project 4.2 Total Land Requirement for the Project 4.3 Present use of any Public Utilized land in the Vicinity of the Project Area 2 4.4 Land Already Purchased, Alienated, Leased and Intended use for Each Plot of Land 4.5. -

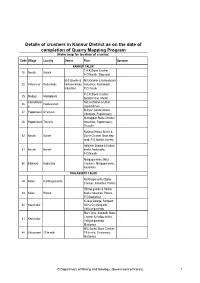

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O. -

CLIVE FARAHAR RARE BOOKS 11 Middle Street Montacute Somerset TA15 6UZ U.K

MONTACUTE MISCELLANY CATALOGUE 94 ITEM 15 CLIVE FARAHAR RARE BOOKS 11 Middle Street Montacute Somerset TA15 6UZ U.K. +44(0)1935 593086 +44(0)7780 434713 [email protected] www. clivefarahar.com CONTENTS AFRICA 3,7,8,15,49. JAPAN 21,30. AMERICAN JUVENILE MANUSCRIPTS 8,10,11,18,20,49. BROADSHEETS 1. MEDCINE 20,38. THE AMERICAS MIDDLE EAST 67. 2,16,23,32,33,62,63,70,89. MILITARY 60. ARAB DICTIONARY POOLE 35. NELSON VICTORY COPPER 69. ASIA 51,52,61,64. PHOTOGRAPHY 29,31. AUSTRALASIA 36 POLARIS NEUCLEAR BAKER (SIR SAMUEL) 3 PROGRAMME 47 BURTON (CAPT. SIR R.F.) 7,8,9. RAEMAEKERS GREAT WAR 97 CALLIGRAPHY 10,11. SHIPWRECKS 54 – 58. CATHOLICISM 12. SLAVERY 50. CHINA 4,6,13,31,40-46, 71-87. TURKEY 66. FRANCE 17. WALEY (ARTHUR)) 71-87. GENERAL 5,10. WEST INDIES 88 GREENLAND 68. WILDE (OSCAR) 89. INDIA 19,22,24 – 29,37, WILLIAM IV CORONATION 90. 48,65,91,97. WORLD WARS I & II 92 - 97. The prices are in pounds sterling. Postage is added at cost. Any item may be returned within a week of receipt for whatever reason. VAT is charged where relevant. My registration number is 941496700. For Bank Transfers National Westminster C.R. Farahar Account no. 50868608 Sort code 60 02 05 1. AMERICAN JUVENILE. A Collection of 43 Hand Coloured Catch Penny Broad Sheets each with between 12 and 20 woodcut illustrations, numbered 7,8,18,19,21 - 50,52-60.12 x 16 ins. 28 x 40.5 cms. some marginal staining affecting a few, Printed expressly for the Humoristic Publishing Co. -

The Chirakkal Dynasty: Readings Through History

THE CHIRAKKAL DYNASTY: READINGS THROUGH HISTORY Kolathunadu is regarded as one of the old political dynasties in India and was ruled by the Kolathiris. The Mushaka vamsam and the kings were regarded as the ancestors of the Kolathiris. It was mentioned in the Mooshika Vamsa (1980) that the boundary of Mooshaka kingdom was from the North of Mangalapuram – Puthupattanam to the Southern boundary of Korappuzha in Kerala. In the long Sanskrit historical poem Mooshaka Vamsam, the dynastic name of the chieftains of north Malabar (Puzhinad) used is Mooshaka (Aiyappan, 1982). In the beginning of the fifth Century A.D., the kingdom of Ezhimala had risen to political prominence in north Kerala under Nannan… With the death of Nannan ended the most glorious period in the history of the Ezhimala Kingdom… a separate line of rulers known as the Mooshaka kings held sway over this area 36 (Kolathunad) with their capital near Mount Eli. It is not clear whether this line of rulers who are celebrated in the Mooshaka vamsa were subordinate to the Chera rulers of Mahodayapuram or whether they ruled as an independent line of kings on their own right (in Menon, 1972). The narration of the Mooshaka Kingdom up to the 12th Century A.D. is mentioned in the Mooshaka vamsa. This is a kavya (poem) composed by Atula, who was the court poet of the King Srikantha of Mooshaka vamsa. By the 14th Century the old Mooshaka kingdom had come to be known as Kolathunad and a new line of rulers known as the Kolathiris (the ‘Colastri’ of European writers) had come into prominence in north Kerala. -

Camp Details (Navy)

CAMP DETAILS (NAVY) AIATC, Kerala 2020 In January 2020, two cadets namely PO Cadet Zeenat Brar and Cadet Gargi Sud of St. Bede's College attended AIATC which was held in Kerala. The camp was conducted at the Indian Naval Academy, Ezhimala, Kannur, Kerela from 9Jan 2020 to 20 Jan 2020. Commander MP Ramesh was the camp commandant for this camp. There were various activities in which the cadets took part. PO Cadet Zeenat Brar took part in group dance, boat pulling and drill. Cadet Gargi Sud took part in group dance, group song, drill and tug of war and also participated in the final cultural program that took place in INA Ramanujan auditorium. Cadets also visited various places in Kerala and were privileged to visit the Indian Naval Academy as well. Directorate Naval Training Camp-1 The camp was held at NCC Academy, Ropar from 12th June 2019 to 21st June 2019. The Cadets that participated for this camp were PO Cadet Zeenat Brar and Cadet Gargi Sood. Various activities were conducted and organized like drill, boat pulling, rigging, fishing, semaphore and swimming. A visit to Anandpur Sahib was also organized. Po Cadet Zeenat Brar participated in the best cadet competition. Annual Training Camp-1 The camp was held at PG College (sector 11), Chandigarh from 1st June 2019 to 10th June 2019. The cadets that participated for the camp were Cadet Gargi Sud, Anushka Tomar, Anushka Sharma, Pallavi Sharma, Sanchita Thakur, Garima Ahuja, Pooja Singh and Zeenat Brar. Various activities were organized like drill, boat pulling, rigging, fishing, semaphore and swimming. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Page Front 1-12.Pmd

REPORT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF KASARAGOD DISTRICT Dr. P. Prabakaran October, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Topic Page No. Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 PART-I LAW AND ORDER *(Already submitted in July 2012) ............................................ 9 PART - II DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE 1. Background ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Development Sectors 2. Agriculture ................................................................................................................................................. 47 3. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development.................................................................................. 113 4. Fisheries and Harbour Engineering................................................................................................... 133 5. Industries, Enterprises and Skill Development...............................................................................179 6. Tourism .................................................................................................................................................. 225 Physical Infrastructure 7. Power .................................................................................................................................................. 243 8. Improvement of Roads and Bridges in the district and development -

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore and the Political Economy of Malabar (1663-1723)

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore and the Political Economy of Malabar (1663-1723) By Binu John Mailaparambil BRILL LEIDEN . BOSTON 2012 CONTENTS Acknowledgements xiii Glossary xv Notes on place and personal names xvii Notes on weights and currencies in Cannanore xviii Maps xix Introduction ] Kolathunadu, 1663-1723 2 Sources 3 Historiographical antecedents 4 Analytical framework 6 Chapter One: The Geo-Political Setting of Kolathunadu 9 Kolathunadu through the ages 9 Malabar: a regional perspective 11 Region within the region: the social world of Kolathunadu 16 Brahmanism in Kolathunadu 18 Nayars as local elites 18 Other social groups 19 Mercantile groups in Kolathunadu 21 Conclusion 22 Chapter Two: The Rajas of Kolathunadu 25 The 'state' in pre-colonial Kerala 25 The 'little kingdom' model 26 The stvarupam polity 28 The concept of sakti 30 Houses by the sea 33 The co-sharers of Kolathunadu 37 Lords of the horses 41 The Arackal Ali Rajas 44 Legitimacy and sakti 47 Conclusion 50 Chapter Three: Lords of the Sea 53 The fifteenth century: decline or continuity? 53 The sixteenth century: changing port order in Malabar 54 The rise of the Mappila trading network in Cannanore 57 x CONTENTS The Cannanore Bazaar 59 The Cannanore thalassocracy 63 Cannanore and the commercial world of the Indian Ocean 66 1. The Arabian Sea 67 2. Ceylon, Coromandel, Bengal, and South-East Asia 71 3. Asian traders in Cannanore 73 4. Cannanore exports 74 5. Cannanore imports 75 Conclusion * 77 Chapter Four: Jan Company in Cannanore (1663—1723) 81 The Malabar commercial scenario -

Important Trade Centers in Malabar Coast Before the Arrival of the Portuguese

IMPORTANT TRADE CENTERS IN MALABAR COAST BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE ARUL S. EVANJALINE ARPUTHA PRIYA Research Scholar, Department of Maritime History and Marine Archaeology, The Tamil University, Thanjavur E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - This study is based on Malabar Coast and its important Ports. The trade in South India were dominated by Malabar Coast on the Arabian Sea and Coromandel Coast on the Bay of Bengal region. The Coromandel coast exported pearls, corals, arcanut, cardamom, silk and cotton textile. Malabar Coast reached its zenith by the coming of the Arabs and the Chinese. Keywords - Malabar, Maritime, Trade, Spices. INTRODUCTION C. Chirakkal Chirakkal the weakest of all four kingdoms of The Malabar coast is basically a dominated by the Malabar, was once popular for pepper,cardamom and Malayalam speaking people. Alexander observers sandalwood trade.After the decline of Kolathunadu that term ‘Malabar’ is not often mentioned in Swaroopam Chirakkal ended to important power in indigenous literature and it is not a indigenous term Malabar. whereas it is referred in Foreign writings. Al Beruni was the first person to use this term. Some sources Cannanore also gives other names for this region like Minibar, The beginning of seventeenth century Cannanore was Manibar, Melibar, Mulaibar etc. Some of the divided into two economic zones. The Europeans in important ports were Onore, Barcelor, Cannanore, Fort Angelo and the Mappila Muslims in Cannanore Calicut, Cochin were important ports. Popular trading bazaar. The European traded pepper. The Cannanore commodities include ginger, pepper, cinnamon, bazaar provided anchorage to ships and boats. cardamoms, bettle, arecanut, coconut, copra, coconut Important commodities for export were spices oil, fine timber for ship building, furniture, rice however to keep up the local demands they traded in butter, sugar, palm sugar and cotton cloth were coconuts products,rice, areca nut in bulk as these exported. -

District Survey Report of Minor Minerals Kannur District

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF MINOR MINERALS (EXCEPT RIVER SAND) Prepared as per Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 issued under Environment (Protection) Act 1986 by DEPARTMENT OF MINING AND GEOLOGY www.dmg.kerala.gov.in November, 2016 Thiruvananthapuram Table of Contents Page no. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Administration ........................................................................................................................... 3 3 Drainage and Irrigation .............................................................................................................. 3 4 Rainfall and climate.................................................................................................................... 4 5 Other meteorological parameters ............................................................................................. 6 5.1 Temperature .......................................................................................................................... 6 5.2 Relative Humidity ................................................................................................................... 6 5.3 Evaporation ............................................................................................................................ 6 5.4 Sunshine Hours ..................................................................................................................... -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

A Peep Into the History of Kottiyoor Migration Sheeba.P.K

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences Vol-6, Issue-2; Mar-Apr, 2021 Journal Home Page Available: https://ijels.com/ Journal DOI: 10.22161/ijels A Peep into the history of Kottiyoor Migration Sheeba.P.K Research Scholar, Kannur University, Kerala, India Received: 09 Feb 2021; Received in revised form: 25 Mar 2021; Accepted: 19 Apr 2021; Available online: 29 Apr 2021 ©2021 The Author(s). Published by Infogain Publication. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Abstract— Migrants act as agents of social change. Migration is a process by which leads to the intermixing of people from diverse cultures. It has many positive contribution such as evolution of composite culture and it also breaks the narrow considerations and widens up the mental horizon of the people at large. Improvement of the quality of life through the transformation of society and by this they improved their standard of living. As part of the Migration to Malabar, we can see its effects on the process of acculturation, adjustment and integration of migrant people at the region of Kottiyoor (Kannur Dt).The present study about Kottiyoor Migration intends to analyze the process of changes in Kottiyoor after migration. Keywords— Kottiyoor Migration, Migra, invasion, conquest. I. INTRODUCTION crime, political stability, more fertile land, lower risk from Migration is one of the oldest activities and it is also a natural hazards etc.So,we can say that migration usually worldwide phenomenon. Migration basically a spatial happens as a result of the combination of these push and mobility from one place to the another.