Ijcem0092463.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Agents – Benefits and New Developments for Cancer Pain

Carr_subbed.qxp 22/5/09 09:49 Page 18 Supportive Oncology Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents – Benefits and New Developments for Cancer Pain a report by Daniel B Carr1 and Marie Belle D Francia2 1. Saltonstall Professor of Pain Research; 2. Special Scientific Staff, Department of Anesthesiology, Tufts Medical Center DOI: 10.17925/EOH.2008.04.2.18 Pain is one of the complications of cancer that patients most fear, and This article surveys the current role of NSAIDs in the management of its multifactorial aetiology makes it one of the most challenging cancer pain and elucidates newly recognised mechanisms that may conditions to treat.1 A systematic review of epidemiological studies on provide a foundation for the next generation of NSAIDs for analgesia cancer pain published between 1982 and 2001 revealed cancer pain for cancer patients. prevalence rates of at least 14%.2 A more recent systematic review identified prevalence rates of cancer pain in as many as one-third of Mechanism of Analgesic Effects patients after curative treatment and two-thirds of patients NSAIDs are a structurally diverse group of compounds known to undergoing treatment regardless of the stage of disease. The wide prevent the formation of prostanoids (prostaglandins and variation in published prevalence rates is due to heterogeneity of the thromboxane) from arachidonic acid through the inhibition of the populations studied, diverse settings, site of primary cancer and stage enzyme cyclo-oxygenase (COX; see Table 1). COX has two isoenzymes: and methodology used to ascertain prevalence.1 COX-1 is found ubiquitously in most tissues and produces prostaglandins and thromboxane, while COX-2 is located in certain A multimodal approach to the treatment of cancer pain that deploys tissues (brain, blood vessels and so on) and its expression increases both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods may be during inflammation or fever. -

Solid Solution Compositions and Use in Chronic Inflammation

(19) *EP003578172A1* (11) EP 3 578 172 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 11.12.2019 Bulletin 2019/50 A61K 9/14 (2006.01) A61K 47/14 (2017.01) A61K 47/44 (2017.01) A61K 31/12 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 19188174.7 A61K 31/137 A61K 31/167 A61K 31/192 (2006.01) A61K 31/216 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 14.01.2014 A61K 31/357 A61K 31/366 A61K 31/4178 (2006.01) A61K 31/4184 (2006.01) A61K 31/522 (2006.01) A61K 31/616 (2006.01) A61K 31/196 (2006.01) (84) Designated Contracting States: • BREW, John AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB London, Greater London EC2Y 8AD (GB) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO • REILEY, Richard Robert PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR London, Greater London EC2Y 8AD (GB) • CAPARRÓS-WANDERLEY, Wilson (30) Priority: 14.01.2013 US 201361752356 P London, Greater London EC2Y 8AD (GB) 04.02.2013 US 201361752309 P (74) Representative: Clements, Andrew Russell Niel et (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in al accordance with Art. 76 EPC: Schlich 14702460.8 / 2 925 367 9 St Catherine’s Road Littlehampton, West Sussex BN17 5HS (GB) (71) Applicant: InFirst Healthcare Limited London EC2Y 8AD (GB) Remarks: This application was filed on 24-07-2019 as a (72) Inventors: divisional application to the application mentioned • BANNISTER, Robin Mark under INID code 62. -

Use of Aspirin and Nsaids to Prevent Colorectal Cancer

Evidence Synthesis Number 45 Use of Aspirin and NSAIDs to Prevent Colorectal Cancer Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-02-0021 Prepared by: University of Ottawa Evidence-based Practice Center at The University of Ottawa, Ottawa Canada David Moher, PhD Director Investigators Alaa Rostom, MD, MSc, FRCPC Catherine Dube, MD, MSc, FRCPC Gabriela Lewin, MD Alexander Tsertsvadze, MD Msc Nicholas Barrowman, PhD Catherine Code, MD, FRCPC Margaret Sampson, MILS David Moher, PhD AHRQ Publication No. 07-0596-EF-1 March 2007 This report is based on research conducted by the University of Ottawa Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. 290-02-0021). Funding was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s), who are responsible for its content, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. No statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help clinicians, employers, policymakers, and others make informed decisions about the provision of health care services. This report is intended as a reference and not as a substitute for clinical judgment. This document is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission except those copyrighted materials noted for which further reproduction is prohibited without the specific permission of copyright holders. -

WO 2009/145921 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 3 December 2009 (03.12.2009) W O 2009/145921 A l (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agents: CASSIDY, Martha et al; Rothwell, Figg, Ernst A61K 31/445 (2006.01) 67UT37/407 (2006.01) & Manbeck, P.C., 1425 K Street, N.W., Suite 800, Wash A61K 31/4545 (2006.01) 67UT 37/79 (2006.01) ington, DC 20005 (US). 67UT 37/55 (2006.01) A61K 31/18 (2006.01) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 67UT 37/495 (2006.01) 67UT 37/54 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, 67UT 37/60 (2006.01) A61P 17/00 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, 67UT 37/796 (2006.01) 67UT 45/06 (2006.01) CA, CH, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, 67UT 37/405 (2006.01) EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (21) International Application Number: HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, PCT/US2009/003320 KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, (22) International Filing Date: NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, 1 June 2009 (01 .06.2009) SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, (25) Filing Language: English UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Horsemen's Information 2016和文TGP 1 薬物修正後 E

[Conditions] 1 Date December 29 (Tue), 2020 2020 Oi Racetrack, Race 10 2 Location TCK, Oi Racetrack 3 Race The 66th Running of Tokyo Daishoten (GI) 4 Eligibility Thoroughbreds, 3 years old & up 5 Full Gate 16 horses 6 Foreign Runners Selected by the selection committee from among the pre-entered horses. 7 Distance 2,000m, 1 1/4 mile (Right-handed, dirt course) 8 Weight 3 years old: 121.5 lbs,4 years old & up: 125.5 lbs, Female: 4.4 lbs less For 3 year-old-horses from the southern hemisphere, reduce 4.4 lbs from the above weight. 9 Purse Unit: 1,000 JPY Prize Purse & Bonus money Running Record 1st place 6th place allowances prize *1 prize *2 1st place 2nd place 3rd place 4th place 5th place or lower Owner 80,000 28,000 16,000 8,000 4,000 300 300 50 1,600 Trainer 880 70 60 50 40 30 30 80 Jockey 120 110 100 80 70 60 30 80 Groom 80 70 60 50 40 30 30 80 Rider 30 30 80 *1 Paid for the runner who broke the previous record and also set the best record during the race. *2 Prize equivalent to the amount listed in the table above is presented. *3 1 USD= 105.88 JPY (As of August,2020) 10 Handling of Late Scratch No allowance is paid in the case of a late scratch (including cancelation of race due to standstill in a starting gate) approved by TCK, Stewards, and Starter. However, if the chairman of the race meeting operation committee deems that the horse is involved in an accident not caused by the horse, the owner is given an running allowance. -

Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Fenamate Analogues: 1,3,4-Oxadiazol-2-Ones and 1,3,4- Oxadiazole-2-Thiones

Scientia Pharmaceutica (Sci. Pharm.) 71,331-356 (2003) O Osterreichische Apotheker-Verlagsgesellschaft m. b.H., Wien, Printed in Austria Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Fenamate Analogues: 1,3,4-Oxadiazol-2-ones and 1,3,4- Oxadiazole-2-thiones Aida A. ~l-~zzoun~'*,Yousreya A ~aklad',Herbert ~artsch~,~afaaA. 2aghary4, Waleed M. lbrahims, Mosaad S. ~oharned~. Pharmaceutical Sciences Dept. (Pharmaceutical Chemistry goup' and Pharmacology group2), National Research Center, Tahrir St. Dokki, Giza, Egypt. 3~nstitutflir Pharmazeutische Chemie, Pharrnazie Zentrum der Universitilt Wien. 4~harmaceuticalChemistry Dept. ,' Organic Chemistry Dept. , Helwan University , Faculty of Pharmacy, Ein Helwan Cairo, Egypt. Abstract A series of fenamate pyridyl or quinolinyl analogues of 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-ones 5a-d and 6a-r, and 1,3,4-oxadiazole-2-thiones 5e-g and 6s-v, respectively, have been synthesized and evaluated for their analgesic (hot-plate) , antiinflammatory (carrageenin induced rat's paw edema) and ulcerogenic effects as well as plasma prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) level. The highest analgesic activity was achieved with compound 5a (0.5 ,0.6 ,0.7 mrnolkg b.wt.) in respect with mefenamic acid (0.4 mmollkg b.wt.). Compounds 6h, 61 and 5g showed 93, 88 and 84% inhibition, respectively on the carrageenan-induced rat's paw edema at dose level of O.lrnrnol/kg b.wt, compared with 58% inhibition of mefenamic acid (0.2mmoll kg b.wt.). Moreover, the highest inhibitory activity on plasma PGE2 level was displayed also with 6h, 61 and 5g (71, 70,68.5% respectively, 0.lmmolkg b.wt.) compared with indomethacin (60%, 0.01 mmolkg b.wt.) as a reference drug. -

Imports of Benzenoid Chemicals and Products

UNITED STATES TARIFF COMMISSION Washington IMPORTS OF BENZENOID CHEMICALS AND PRODUCTS 1970 United States General Imports of Intermediates, Dyes, Medicinals, Flavor and Perfume Materials, and Other Finished Benzenoid Products Entered in 1970 Under Schedule 4, Part 1, of The Tariff Schedules of the United States TC Publication 413 United States Tariff Commission August 1971 UNITED STATES TARIFF COMMISSION Catherine Bedell, chairwm Glenn W. Sutton Will E. Leonard, Jr. George M. Moore J. Banks Young Kenneth R. Mason, Secretary Address all communications to United States Tariff Commission Washington, D.C. 20436 CONTENTS (Imports under TSUS, Schedule 4, Parts 18 and 1C) Table No. Page 1. Benzenoid intermediates: Summary of U.S. general imports entered under Part 1B, TSUS, by competitive status, 1970---- 6 Benzenoid intermediates: U.S. general imports entered under Part 1B, TSUS, by country of origin, 1970 and 1969---- 6 3. Benzenoid intermediates: U.S. general imports entered under Part 1B, TSUS, showing competitive status, 1970 8 4. Finished benzenoid products: Summary of U.S. general im- ports entered under Part 1C, TSUS, by competitive status, 1970 27 5. Finished benzenoid products: U.S. general imports entered under Part 1C, TSUS, by country of origin, 1970 and 1969 ---- 28 6. Finished benzenoid products: Summary of U.S. general imports entered under Part 1C, TSUS, by major groups and competitive status, 1970 30 7. Benzenoid dyes: U.S. general imports entered under Part 1C, TSUS, by class of application, and competitive status, 1970-- 33 8. Benzenoid dyes: U.S. general imports entered under Part 1C, TSUS, by country of origin, 1970 compared with 1969 34 9. -

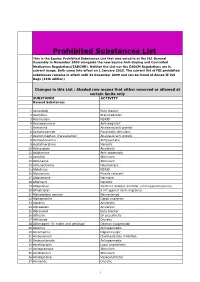

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Minella Et Al-2019 Degradation

Degradation of ibuprofen and phenol with a Fenton-like process triggered by zero-valent iron (ZVI-Fenton) Marco Minella, Stefano Bertinetti, Khalil Hanna, Claudio Minero, Davide Vione To cite this version: Marco Minella, Stefano Bertinetti, Khalil Hanna, Claudio Minero, Davide Vione. Degradation of ibuprofen and phenol with a Fenton-like process triggered by zero-valent iron (ZVI-Fenton). Envi- ronmental Research, Elsevier, 2019, 179 (Pt A), pp.108750. 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108750. hal- 02307030 HAL Id: hal-02307030 https://hal-univ-rennes1.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02307030 Submitted on 26 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Degradation of ibuprofen and phenol with a Fenton- like process triggered by zero-valent iron (ZVI-Fenton) Marco Minella, a Stefano Bertinetti, a Khalil Hanna, b Claudio Minero, a Davide Vione * a a Dipartimento di Chimica, Università di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 5, 10125 Torino, Italy b Univ Rennes, Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Chimie de Rennes, CNRS, ISCR – UMR6226, F-35000 Rennes, France. * Correspondence. Tel: +39-011-6705296; Fax +39-011-6705242. E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: Marco Minella: 0000-0003-0152-460X Khalil Hanna: 0000-0002-6072-1294 Claudio Minero: 0000-0001-9484-130X Davide Vione: 0000-0002-2841-5721 Abstract It is shown here that ZVI-Fenton is a suitable technique to achieve effective degradation of ibuprofen and phenol under several operational conditions. -

An Investigation of the Polymorphism of a Potent Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Flunixin

CrystEngComm An Investigation of the Polymorphism of a Potent Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Flunixin Journal: CrystEngComm Manuscript ID CE-ART-10-2019-001619.R1 Article Type: Paper Date Submitted by the 09-Nov-2019 Author: Complete List of Authors: Liu, Hao; Wuhan Institute of Technology Yang, Xing; Wuhan Institute of Technology Wu, Shanyu; Nankai University Zhang, Mingtao; Purdue University System, IPPH; Nankai University, Parkin, Sean; University of Kentucky, Chemistry Cao, Shuang; Wuhan Institute of Technology Li, Tonglei; Purdue University, Yu, Faquan; Wuhan Institute of Technology Long, Sihui; Wuhan Institute of Technology, School of Chemical Engineering and Pharmacy Page 1 of 24 CrystEngComm An Investigation of the Polymorphism of a Potent Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Flunixin Hao Liu1, Xing Yang1, Shanyu Wu2, Mingtao Zhang2, Sean Parkin3, Shuang Cao1, Tonglei Li4, Faquan Yu1#, Sihui Long1* 1. H. Liu, X. Yang, Dr. S. Cao, Dr. F. Yu, Dr. S. Long Key Laboratory for Green Chemical Process of Ministry of Education Hubei Key Laboratory of Novel Reactor and Green Chemical Technology Hubei Engineering Research Center for Advanced Fine Chemicals School of Chemical Engineering and Pharmacy Wuhan Institute of Technology 206 1st Rd Optics Valley, East Lake New Technology Development District, Wuhan, Hubei 430205, China Phone: (027) 87194980 Email: [email protected] [email protected]; [email protected] 2. S. Wu, Dr. M. Zhang Computational Center for Molecular Science, College of Chemistry, Nankai University, Tianjin, China 3. Dr. S. Parkin Department of Chemistry, University of Kentucky, 1 CrystEngComm Page 2 of 24 Lexington, Kentucky 40506, United States 4. Dr. T. Li Department of Industrial and Physical Pharmacy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, United States H. -

Tramadol: a Review of Its Use in Perioperative Pain

Drugs 2000 Jul; 60 (1): 139-176 ADIS DRUG EVA L U AT I O N 0012-6667/00/0007-0139/$25.00/0 © Adis International Limited. All rights reserved. Tramadol A Review of its Use in Perioperative Pain Lesley J. Scott and Caroline M. Perry Adis International Limited, Auckland, New Zealand Various sections of the manuscript reviewed by: S.R. Abel, Indiana University Medical Centre, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA; S.S. Bloomfield, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA; J.E. Caldwell, Department of Anesthesia, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA; K.A. Lehmann, Institute of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; L. Radbruch, Institute of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; K. Szymanski, Indiana University Medical Centre, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA; P. Tarkkila, Department of Anaesthesia, Helsinki University Centre Hospital, Helsinki, Finland; C.H. Wilder-Smith, Gastrointestinal Unit and Nociception Research Group, Berne, Switzerland. Data Selection Sources: Medical literature published in any language since 1993 on tramadol, identified using AdisBase (a proprietary database of Adis International, Auckland, New Zealand) and Medline. Additional references were identified from the reference lists of published articles. Bibliographical information, including contributory unpublished data, was also requested from the company developing the drug. Search strategy: AdisBase search terms were ‘tramadol’ or ‘CG-315’ or ‘CG-315E’ or ‘U-26225A’. Medline search terms were ‘tramadol’. Searches were last updated 26 May 2000. Selection: Studies in patients with perioperative moderate to severe pain who received tramadol. Inclusion of studies was based mainly on the methods section of the trials. When available, large, well controlled trials with appropriate statistical methodology were preferred. -

Allergic and Photoallergic Contact Dermatitis to Topical Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: a Case Series from Turkey

CONTACT DERMATITIS AND OCCUPATIONAL DERMATOSES ALLERGIC AND PHOTOALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS TO TOPICAL NON-STEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS: A CASE SERIES FROM TURKEY E Ozkaya (1) - A Kutlay (1) Istanbul University Istanbul Medical Faculty, Dermatology, Istanbul, Turkey (1) Background: Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used, mainly for soft tissue pain and injury. Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and photoallergic contact dermatitis (PACD) from topical NSAIDs have been reported with an increasing incidence. Ketoprofen seems to be the major culprit drug, followed by etofenamate and bufexamac in many European countries. There are only limited data on this subject in Turkey. Observation: Out of 2375 consecutively patch tested patients in our clinic between 1996 and 2017, 13 patients (7 male, 6 female, age range: 21-81, median: 56 years) (0.5%) were diagnosed with topical NSAID-induced ACD/PACD. Patients were patch tested (n=13) and photopatch tested (n=4) with the suspected topical preparations as is, and with the active (n=4) and inactive ingredients, when available, in addition to the European baseline series. Etofenamate (tested in a dilution series of 1%-5%-10% in petrolatum and aqua) was the leading culprit drug in 8 patients (62%), followed by ketoprofen (n=2), diclofenac (n=2), and diethylamine salicylate & naproxen (n=1). The main diagnosis was ACD whereas PACD was diagnosed in 2 patients from etofenamate and ketoprofen. Concomitant positive reaction were observed with inactive ingredients such as benzyl alcohol in etofenamate, and neroli oil in ketoprofen preparations, respectively. Cross-reaction to fragrances (fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, cinnamic alcohol/aldehyde) was present in both patients with ketoprofen allergy.