Constructions of Latinidad in Jane the Virgin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Injuries Associated with Posthole Diggers

FARM MACHINERY INJURY Injuries associated with posthole diggers A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by J Miller, L Fragar and R Franklin Published September 2006 RIRDC Publication No 06/036 RIRDC Project No US-87A © Australian Centre for Agricultural Health and Safety and Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved ISBN 1 74151 299 9 ISSN 1440-6845 Farm Machinery Injury: Injuries Associated with Posthole Diggers Publication No. 06/036 Project No. US-87A The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable industries. The information should not be relied upon for the purpose of a particular matter. Specialist and/or appropriate legal advice should be obtained before any action or decision is taken on the basis of any material in this document. The Commonwealth of Australia, Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, the authors or contributors do not assume liability of any kind whatsoever resulting from any person's use or reliance upon the content of this document. This publication is copyright. However, ACAHS and RIRDC encourage wide dissemination of their research providing that these organisations are clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction contact the RIRDC Production Manager on Ph 61 (0) 2 6272 3186 or the Manager on 61 (0)2 6752 8215. Research contact details L Fragar Australian Centre for Agricultural Health and Safety University of Sydney PO Box 256 Moree NSW 2400 Australia Phone: 61 2 67528210 Fax 61 2 67526639 E-Mail: [email protected] RIRDC Contact details: Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 2, 15 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4218 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected]. -

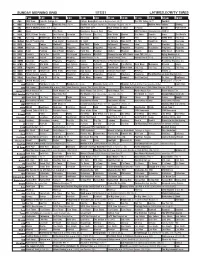

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Iowa at Northwestern. (N) Å The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Washington Capitals at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Å Mecum Auto Auctions Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Emeril Pain Relief! 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News at 9am News AKC National Championship 2020 Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest Sex Abuse Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse AAA PiYo Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Paid Prog. 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch On Camera Rare 1899 Dr. Ho’s Caught on News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Smile Copper Workout! AAA New YOU! Smile Bathroom? Cleanse Ideal AAA Prostate Paid Prog. 2 2 KWHY Más Pelo Programa Resultados Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Resultados Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Lidia Milk Street Field Trip 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 3 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Amazing Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

300 Series Two Man Hole Diggers Operator Manuals

OPERATOR MANUAL Includes Safety, Service and Replacement Part Information 300 Series Hole Diggers Models: 330H, 343H, 357H Form: GOM12070702 Version 1.2 Do not discard this manual. Before operation, read and comprehend its contents. Keep it readily available for reference during operation or when performing any service related function. When ordering replacement parts, please supply the following information: model number, serial number and part number. For customer service assistance, telephone 800.533.0524, +507.451.5510. Our Customer Service Department telefax number is 877.344.4375 (DIGGER 5), +507.451.5511. There is no charge for customer service activities. Internet address: http://www.generalequip.com. E-Mail: [email protected]. The products covered by this manual comply with the mandatory requirements of 98/37/EC. Copyright 2009, General Equipment Company. Manufacturers of light construction equipment Congratulations on your decision to purchase a General light construction product. From our humble beginnings in 1955, it has been a continuing objective of General Equipment Company to manufacture equipment that delivers uncompromising value, service life and investment return. Because of this continuous commitment for excellence, many products bearing the General name actually set the standards by which competitive products are judged. When you purchased this product, you also gained access to a team of dedicated and knowledgeable support personnel that stand willing and ready to provide field support assistance. Our team of sales representatives and in house factory personnel are available to ensure that each General product delivers the intended performance, value and investment return. Our personnel can readily answer your concerns or questions regarding proper applications, service requirements and warranty related problems. -

The Analysis of Transition in Woman Social Status—Comparing Cinderella with Ugly Betty

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. 746-752, September 2010 © 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.1.5.746-752 The Analysis of Transition in Woman Social Status—Comparing Cinderella with Ugly Betty Tiping Su Huaiyin Normal University, Huai’an, China Email: [email protected] Qinyi Xue Huaiyin Normal University, Huai’an, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—Cinderella, a perfect fairly tale girl has been widely known to the world. Its popularity reveals the universal Cinderella Complex hidden behind the woman status. My thesis focuses its attention on the transition in woman status. First, it looks into the Cinderella paradigm as well as its complex in reality. Second, it finds the transcendence in modern Cinderella. The last part pursues the development of women status’ improvement. In current study, seldom people make comparisons between Cinderella and Ugly Betty. With its comparison and the exploration of feminism, it can be reached that woman status have been greatly improved under the influence of different factors like economic and political. And as a modern woman lives in the new century, she has to be independent in economy and optimistic in spirit. Index Terms—Cinderella Complex, Ugly Betty, feminist movement, feminine consciousness, women status I. INTRODUCTION Cinderella, a beautiful fairy tale widely known around the world, has become a basic literary archetype in the world literature. Its popularity reveals the universal Cinderella Complex hidden behind the human’s consciousness. With the development of feminine, women came to realize their inner power and the meaning of life. -

Building Community by Producing Honk! Jr., a Musical Based on the Glu Y Duckling Heidi Louise Jensen

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Theses Student Research 5-1-2013 Two hundred year old lesson in bullying: building community by producing Honk! Jr., a musical based on The glU y Duckling Heidi Louise Jensen Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses Recommended Citation Jensen, Heidi Louise, "Two hundred year old lesson in bullying: building community by producing Honk! Jr., a musical based on The Ugly Duckling" (2013). Theses. Paper 38. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2013 HEIDI LOUISE JENSEN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School A TWO HUNDRED YEAR OLD LESSON IN BULLYING: BUILDING COMMUNITY BY PRODUCING HONK! JR., A MUSICAL BASED ON “THE UGLY DUCKLING” A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Heidi Louise Jensen College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Theatre Arts and Dance Theatre Education May 2013 This Thesis by: Heidi Louise Jensen Entitled: A Two Hundred Year Old Lesson in Bullying: Building Community by Producing HONK! Jr., A Musical Based on “The Ugly Duckling”. has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts in College of Performing and Visual Arts in School of Theatre and Dance, Program of Theatre Educator Intensive Accepted by the Thesis Committee _______________________________________________________ Gillian McNally, Associate Professor, M.F.A., Chair, Advisor _______________________________________________________ Mary J. -

Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Moldova: Does Moldova's Eastern Orientation Inhibit Its European Aspirations?

“Foreign affairs of the Republic of Moldova: Does Moldova’s Eastern orientation inhibit its European aspirations?” Liliana Viţu 1 CONTENTS: List of abbreviations Introduction Chapter I. Historic References…………………………………………………………p.1 Chapter II. The Eastern Vector of Moldova’s Foreign Affairs…………………..p.10 Russian Federation – The Big Brother…………………………………………………p.10 Commonwealth of Independent States: Russia as the hub, the rest as the spokes……………………………………………………….…………………………….p.13 Transnistria- the “black hole” of Europe………………………………………………..p.20 Ukraine – a “wait and see position”…………………………………………………….p.25 Chapter III. Moldova and the European Union: looking westwards?………….p.28 Romania and Moldova – the two Romanian states…………………………………..p.28 The Council of Europe - Monitoring Moldova………………………………………….p.31 European Union and Moldova: a missed opportunity?………………………………p.33 Chapter IV. Simultaneous integration in the CIS and the EU – a contradiction in terms ……………………………………………………………………………………...p.41 Conclusions Bibliography 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ASSMR – Autonomous Soviet Socialist Moldova Republic CEEC – Central-Eastern European countries CIS – Commonwealth of Independent States CoE – Council of Europe EBRD – European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ECHR – European Court of Human Rights EU – European Union ICG – International Crisis Group IPP – Institute for Public Policy NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organisation NIS – Newly Independent States OSCE – Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe PCA – Partnership and Cooperation Agreement PHARE – Poland Hungary Assistant for Economic Reconstruction SECI – South East European Cooperation Initiative SPSEE – Stability Pact for South-Eastern Europe TACIS – Technical Assistance for Commonwealth of Independent States UNDP – United Nations Development Program WTO – World Trade Organization 3 INTRODUCTION The Republic of Moldova is a young state, created along with the other Newly Independent States (NIS) in 1991 after the implosion of the Soviet Union. -

Reporte De Telenovelas De Los 80'S 1. COLORINA : Fue Producida En

Reporte de Telenovelas de los 80’s 1. COLORINA : Fue producida en 1980 por Valentín Pimstein considerado uno de los padres de la novela rosa en México, protagonizada por la actriz Lucia Méndez y Enrique Álvarez Félix ; como villanos la telenovela tuvo a José Alonso y a María Teresa Rivas . Contó además con las actuaciones de María Rubio, Julissa y Armando Calvo. Causo impacto en la sociedad al ser la primera telenovela con clasificación C y en ser transmitada a las 23:00 hrs. Además de romper record de llamadas por el concurso convocado para saber quien seria e hijo de colorina. Fue rehecha en 1993 en argentina bajo el titulo de Apasionada. En 2001 por televisa, ahora a mano de Juan Osorio y titulada Salome. Y finalmente fue retransmitida en 2 ocasiones por el canal Tlnovelas siendo la última el 9 de julio del 2012. En marzo del 2011 la revista People en España la considero entre las mejores 20 novelas de la historia. 2. CHISPITA: Fue producida en 1982 producida por Valentin Pimstein, protagonizada adultamente por adultamente por Angélica Aragón y Enrique Lizalde con las participaciones protagonicas infantiles de Lucero y Usi Velasco. En 1983 fue ganadora en los premios TVyNovelas por mejor actriz infantil la actriz Lucero. Lucero actualmente tiene 33 años de carrera artística , a realizado 9 telenovelas , cuanta con mas de 30 premios entre cantante y actriz. Fue remasterizada en 1996 por Televisa bajo el nombre de Luz Clarita. 3. EL DERECHO DE NACER: Está basada en la radio novela cubana, pero en 1981 es transmitida por Televisa baja la producción de Ernesto Alonso y protagonizada por Verónica Castro y Sergio Jiménez, con las participaciones estelares de Humberto Zurita y Erika Buenfil. -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

DGA's 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lily Bedrossian August 25, 2015 (310) 289-5334 DGA’s 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals: Employer Hiring of Women Directors Shows Modest Improvement; Women and Minorities Continue to be Excluded In First-Time Hiring LOS ANGELES – The Directors Guild of America today released its annual report analyzing the ethnicity and gender of directors hired to direct primetime episodic television across broadcast, basic cable, premium cable, and high budget original content series made for the Internet. More than 3,900 episodes produced in the 2014- 2015 network television season and the 2014 cable television season from more than 270 scripted series were analyzed. The breakdown of those episodes by the gender and ethnicity of directors is as follows: Women directed 16% of all episodes, an increase from 14% the prior year. Minorities (male and female) directed 18% of all episodes, representing a 1% decrease over the prior year. Positive Trends The pie is getting bigger: There were 3,910 episodes in the 2014-2015 season -- a 10% increase in total episodes over the prior season’s 3,562 episodes. With that expansion came more directing jobs for women, who directed 620 total episodes representing a 22% year-over-year growth rate (women directed 509 episodes in the prior season), more than twice the 10% growth rate of total episodes. Additionally, the total number of individual women directors employed in episodic television grew 16% to 150 (up from 129 in the 2013-14 season). The DGA’s “Best Of” list – shows that hired women and minorities to direct at least 40% of episodes – increased 16% to 57 series (from 49 series in the 2013-14 season period). -

SAFER at HOME in Select Theaters, VOD & Digital on February 26, 2021

SAFER AT HOME In Select Theaters, VOD & Digital on February 26, 2021 DIRECTED BY Will Wernick WRITTEN BY Will Wernick, Lia Bozonelis PRODUCED BY Will Wernick, John Ierardi, Bo Youngblood, Lia Bozonelis (Co-Producer), Jason Phillips (Co-Producer) STARRING Jocelyn Hudon, Emma Lahana, Alisa Allapach, Adwin Brown, Dan J. Johnson, Michael Kupisk, Daniel Robaire RUN TIME: 82 mins DISTRIBUTED BY: Vertical Entertainment For additional information please contact: LA Daniel Coffey – [email protected] Emily Maroon – [email protected] NY Susan Engel – [email protected] Danielle Borelli – [email protected] ABOUT THE FILM Synopsis Two years into the pandemic, a group of friends throw an online party with a night of games, drinking and drugs. After taking an ecstasy pill, things go terribly wrong and the safety of their home becomes more terrifying than the raging chaos outside. Director’s Statement Making Safer at Home was challenging. Not just because of the technical hurdles the pandemic mandated, but because of the strange new features life had taken on in those early months of the pandemic. I found myself having unusual conversations, and realizations about myself and friends — things that only this type of stress could bring out. I noticed people making major, sometimes life changing decisions, quickly. Brake-ups, pregnancies, divorces, fights-- this instigated them all. Almost everyone I knew was caught in an indefinite cycle of every day feeling the same. And then we started working on this film. Safer at Home plays out essentially in real time, and shows what a long period of lockdown could do to a group of friends. -

Genetics Was the Key Old Furniture, Tires, Mattresses and More Into the Scrubtown Sinkhole

A3 SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 4, 2018 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $2 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM SUNDAY + PLUS >> Tigers 1B Just what WHOLE we’ve been roll LOTTA waiting for over BULL 1D Opinion/4A Bolles TASTE BUDDIES See 6C COMMUNITY CLEANUP TOP BANANA MODERN VERSION OF THE FRUIT OWES ITS EXISTENCE TO THIS LAKE CITY MAN Photos by TONY BRITT/Lake City Reporter A volunteer drags a garbage can loaded with debris from the sinkhole on Scrubtown Road Saturday. Around 20 volunteers pitched in to help. SCRUBTOWN SCRUB DOWN Photos by CARL MCKINNEY/Lake City Reporter Furniture, mattresses, Nader Vakili holds up two hands of bananas, which are commonly misidentified more pulled from pit. as bunches. Vakili’s work as a plant geneticist-pathologist was used to breed modern bananas found in grocery stores. By TONY BRITT [email protected] FORT WHITE — For gen- erations people threw garbage, Genetics was the key old furniture, tires, mattresses and more into the Scrubtown sinkhole. Nader Vakili figured Saturday, around 20 volun- out how to breed a teers and members of various sterile ‘mutant’ plant. environmental groups gathered at the sinkhole to clean the By CARL MCKINNEY debris from the area. Less than [email protected] three hours in, they had nearly filled a 30-cubic-yard trash bin. A piece of Nader Vakili The group plans to return next is in the bananas sold in Saturday. grocery stores throughout “We’re holding a cleanup for the world. this sinkhole on Scrubtown Eric Wise struggles to keep his footing Vakili explained the Saturday. -

Teoría Y Evolución De La Telenovela Latinoamericana

TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Laura Soler Azorín Soler Laura TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Director: José Carlos Rovira Soler Octubre 2015 TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Tesis de doctorado Dirigida por José Carlos Rovira Soler Universidad de Alicante Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Filología Española, Lingüística General y Teoría de la Literatura Octubre 2015 A Federico, mis “manos” en selectividad. A Liber, por tantas cosas. Y a mis padres, con quienes tanto quiero. AGRADECIMIENTOS. A José Carlos Rovira. Amalia, Ana Antonia, Antonio, Carmen, Carmina, Carolina, Clarisa, Eleonore, Eva, Fernando, Gregorio, Inma, Jaime, Joan, Joana, Jorge, Josefita, Juan Ramón, Lourdes, Mar, Patricia, Rafa, Roberto, Rodolf, Rosario, Víctor, Victoria… Para mis compañeros doctorandos, por lo compartido: Clara, Jordi, María José y Vicent. A todos los que han ESTADO a mi lado. Muy especialmente a Vicente Carrasco. Y a Bernat, mestre. ÍNDICE 1.- INTRODUCCIÓN. 1.1.- Objetivos y metodología (pág. 11) 1.2.- Análisis (pág. 11) 2.- INTRODUCCIÓN. UN ACERCAMIENTO AL “FENÓMENO TELENOVELA” EN ESPAÑA Y EN EL MUNDO 2.1.-Orígenes e impacto social y económico de la telenovela hispanoamericana (pág. 23) 2.1.1.- El incalculable negocio de la telenovela (pág. 26) 2.2.- Antecedentes de la telenovela (pág. 27) 2.2.1.- La novela por entregas o folletín como antecedente de la telenovela actual. (pág. 27) 2.2.2.- La radionovela, predecesora de la novela por entregas y antecesora de la telenovela (pág. 35) 2.2.3.- Elementos comunes con la novela por entregas (pág.