A School for the Nation? a School for Ronald R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

Washington Monthly 2018 College Rankings

The Prison-to-School Pipeline 2018 COLLEGE RANKINGS What Can College Do For You? PLUS: The best—and worst— colleges for vocational certificates Which colleges encourage their students to vote? Why colleges should treat SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN students like numbers All Information Fixing higher education deserts herein is confidential and embargoed Everything you always wanted to know through Aug. 23, 2018 about higher education policy VOLUME 50 NUMBER 9/10 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 SOCIAL MOBILITY RESEARCH SERVICE Features NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES THE 2018 COLLEGE GUIDE *Public institution Introduction: A Different Kind of College Ranking 15 °For-profit institution by Kevin Carey America’s Best and Worst Colleges for%offederalwork-studyfunds Vocational Certificates 20 GraduationGrad rate rate rank performancePell graduationPell rank performance gap rankFirst-gen rank performancerankEarningsperformancerankNoNetpricerank publicationRepaymentrankPredictedrepaymentraterankResearch has expendituresBachelor’stoPhDrank everScience&engineeringPhDsrank rank rankedFacultyawardsrankFacultyinNationalAcademiesrank thePeaceCorpsrank schoolsROTC rank wherespentonservicerankMatchesAmeriCorpsservicegrants? millionsVotingengagementpoints of Americans 1 Harvard University (MA) 3 35 60 140 41 2seek 5 168 job310 skills.8 Until10 now.17 1 4 130 188 22 NO 4 2 Stanford University (CA) 7 128 107 146 55 11 by2 Paul16 48Glastris7 6 7 2 2 70 232 18 NO 1 3 MA Institute of Technology (MA) 16 234 177 64 48 7 17 8 89 13 2 10 3 3 270 17 276 NO 0 4 Princeton University (NJ) 1 119 100 100 23 20 Best3 30 &90 Worst67 Vocational5 40 6 5 Certificate117 106 203 ProgramsNO 1 Rankings 22 5 Yale University (CT) 4 138 28 121 49 22 America’s8 22 87 18Best3 Colleges39 7 9 for134 Student22 189 VotingNO 0 28 6 Duke University (NC) 9 202 19 156 218 18 Our26 15 first-of-its-kind183 6 12 list37 of9 the15 schools44 49doing215 theNO most3 to turn students into citizens. -

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

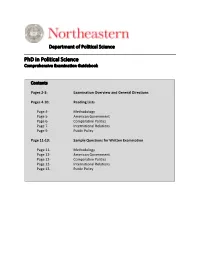

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Kansas Alumni Magazine

,0) Stormwatch THE FLYING JAYHAWKS AND ALUMNI HOLIDAYS PRESENT CRUISE THE PASSAGE OF PETER THE GREAT AUGUST 1 - AUGUST 14, 1991 Now, for the first time ever, you can follow in the historic pathways of Peter the Great, the powerful Russian czar, as you cruise from Leningrad, Peter's celebrated capital and "window on the West," all the way to Moscow ... on the waterways previously accessible only to Russians. See the country as Peter saw it, with its many treasures still beautifully preserved and its stunning scenery virtually untouched. Come join us as we explore the Soviet Union's bountiful treas- ures and traditions amidst today's "glasnost" and spirit of goodwill. From $3,295 per person from Chicago based on double occupancy CRUISE GERMANY'S MAGNIFICENT EAST ON THE ELBE JULY 27 - AUGUST 8, 1991 A new era unfolds... a country unites ... transition is underway in the East ... Germany's other great river, The Elbe, beckons for the first time in 45 years! Be a part of history! This landmark cruise is a vision that has taken years to realize. Reflected in the mighty Elbe's tranquil waters are some of the most magnificent treasures of the world: renaissance palaces, spired cathedrals, ancient castles... all set amidst scenery so beautiful it will take your breath away! Add to this remarkable cruise, visits to two of Germany's favorite cities, Hamburg and Berlin, and the "Golden City" of Prague, and you have a trip like none ever offered before. From $3,795 per person from Chicago based on double occupancy LA BELLE FRANCE JUNE 30-JULY 12, 1991 There is simply no better way to describe this remarkable melange of culture and charm, gastronomy and joie de vivre. -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

Us-Libya Claims Agreement - Background

US-LIBYA CLAIMS AGREEMENT - BACKGROUND US State Department Press Release: On August 14, 2008, the United States and Libya signed a comprehensive claims settlement agreement in Tripoli. The agreement is designed to provide rapid recovery of fair compensation for American nationals with terrorism-related claims against Libya. It will also address Libyan claims arising from previous U.S. military actions. The agreement is being pursued on a purely humanitarian basis and does not constitute an admission of fault by either party. Rather, pursuant to the agreement an international Humanitarian Settlement Fund will be established in Libya to collect the necessary resources for the claims on both sides. No U.S. appropriated funds will be contributed, and any contributions by private parties will be voluntary. Each side will be responsible for distributing the resources it receives to its own nationals and to ensure the dismissal of any related court actions. The U.S. Congress has supported this initiative by passing the Libyan Claims Resolution Act, which was signed into law by the President on August 4. The law authorizes the Secretary of State to immunize the assets of the Humanitarian Settlement Fund so they will reach the intended recipients. The law also provides that Libya’s immunity from terrorism-related court actions will be restored when the Secretary of State certifies that the United States has received sufficient funds to pay the Pan Am 103 and La Belle Discotheque settlements and to provide fair compensation for American deaths and physical injuries in other pending cases against Libya. The resources under the agreement are expected to be sufficient to fulfill further purposes such as additional recoveries for death and physical injury because of special circumstances, claims for emotional distress, and terrorism-related claims by commercial parties. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

HS373 Readings from German History Credit : 3-0-0-3 Approval: Approved in 3Rd Senate Students Intended For: B.Tech

HS373 Readings from German History Credit : 3-0-0-3 Approval: Approved in 3rd Senate Students intended for: B.Tech. Elective or Core: Elective Prerequisite: Consent of the faculty member Semester: Even/Odd Common European Frame of Reference Norms (Level B 2) Course objective The course offers a broad survey of German history. It seeks to promote in the main advanced reading comprehension in German through a systematic study of carefully graded texts and (slightly abridged) original materials that deal with major landmarks in German history from 1806 to the present. Course Content: Select Reading Material on: The Birth of the German Nation (1806 – 1848); Prussia and Austria 1848 – 1871; the Nation State; Empire and Colonial Ambitions (1890 – 1910); from World War I to the Weimar Republic (1914 – 1933); Nazi Germany (1933 – 1942); Finis Germaniae to the Basic Law (1942 – 1949); Divided Legacy (1949 – 1990); United Germany Method of Evaluation 2 Quizzes (10 Marks each), Assignment (10 Marks), Attendance and Participation (10 Marks) and End of Semester Examination (50 Marks) Prescribed Texts: Excerpts from: Heinz Ludwig Arnold: Deutschland! Deutschland? Texte aus 500 Jahren von Martin Luther bis Günter Grass. Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2002. Hagen Schulze: Kleine deutsche Geschichte. Mit Bildern aus dem Deutschen Historischen Museum. Munich: Beck, 1996. Select References Karin Hermann: Reading German History. A German Reading Course for Beginners. Munich: Max Hueber, 1992. Eberhard Jäckel: Das deutsche Jahrhundert. Eine historische Bilanz. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1996. Martin Kitchen: The Cambridge Illustrated History of Germany. Cambridge: CUP, 2000. Klaus Schulz: Aus deutscher Vergangenheit. Ein geschichtlicher Überblick. Munich: Max Hueber, 1971. -

The Broken Promises of an All-Volunteer Military

THE BROKEN PROMISES OF AN ALL-VOLUNTEER MILITARY * Matthew Ivey “God and the soldier all men adore[.] In time of trouble—and no more, For when war is over, and all things righted, God is neglected—and the old soldier slighted.”1 “Only when the privileged classes perform military service does the country define the cause as worth young people’s blood. Only when elite youth are on the firing line do war losses become more acceptable.”2 “Non sibi sed patriae”3 INTRODUCTION In the predawn hours of March 11, 2012, Staff Sergeant Robert Bales snuck out of his American military post in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and allegedly murdered seventeen civilians and injured six others in two nearby villages in Panjwai district.4 After Bales purportedly shot or stabbed his victims, he piled their bodies and burned them.5 Bales pleaded guilty to these crimes in June 2013, which spared him the death penalty, and he was sentenced to life in prison without parole.6 How did this former high school football star, model soldier, and once-admired husband and father come to commit some of the most atrocious war crimes in United States history?7 Although there are many likely explanations for Bales’s alleged behavior, one cannot help but to * The author is a Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy. This Article does not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, the United States Navy, or any of its components. The author would like to thank Michael Adams, Jane Bestor, Thomas Brown, John Gordon, Benjamin Hernandez- Stern, Brent Johnson, Michael Klarman, Heidi Matthews, Valentina Montoya Robledo, Haley Park, and Gregory Saybolt for their helpful comments and insight on previous drafts. -

Overuse White Paper Formatted

White Paper Series Ranking and analysis of overuse in U.S. hospitals EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Overuse, which is also known as low-value care, is often defined as the provision of health care services for which the potential for harm exceeds the likely benefit to a patient. Overuse occurs in all healthcare settings, including hospitals. It exposes patients to preventable harm and wastes more than $100 billion each year. To date, no study has published the rate of overuse in specific U.S. hospitals. The Lown Institute Hospital Index is the first hospital ranking to grade individual hospitals by how well they avoid overuse. This white paper provides an analysis of the overuse of 13 low-value services in 3,282 U.S. hospitals using Medicare data. These 13 services include imaging tests, surgeries, and cardiovascular procedures, and have all been validated in previous studies of low-value care. Only instances of these services deemed inappropriate in the literature were counted as overuse. Hospitals that did not have the capacity to perform a specific low-value procedure did not have that service counted in their total grade. We find that overuse varies across hospitals by type, size, and location. Teaching hospitals, larger hospitals, urban hospitals, and for-profit hospitals on average ranked lower for avoiding overuse overall, compared to non-teaching, smaller, rural hospitals. However, these patterns were not always consistent across all low-value services. Safety net hospitals and small rural hospitals had higher rankings in avoiding overuse overall, but their scores differed by specific low-value service. For-profit hospitals consistently ranked lower than nonprofit hospitals for avoiding nearly every low-value service measured.