Dissertation Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Communities in the Developing World Scientific Communities in the Developing World

Scientific Communities in the Developing World Scientific Communities in the Developing World Edited by jacques Caillard V.V. Krishna Roland Waast Sage Publications New Delhiflhousand Oaks/London Copyright @) Jacques Gaillard, V.V. Krishna and Roland Waast, 1997. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 1997 by Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd M-32, Greater Kailash Market I New Delhi 110 048 Sage Publications Inc Sage Publications Ltd 2455 Teller Road 6 Bonhill Street Thousand Oaks, California 91320 London EC2A 4PU Published by Tejeshwar Singh for Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd, phototypeset by Pagewell Photosetters, Pondicherry and printed at Chaman Enterprises, Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Scientific communities in the developing world I edited by Jacques Gaillard, V.V. Krishna, Roland Waast. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Science-Developing countries--History. 2. Science-Social aspect- Developing countries--History. I. Gaillard, Jacques, 1951- . 11. Krishna, V.V. 111. Waast, Roland, 1940- . Q127.2.S44 306.4'5'091724--dc20 1996 9617807 ISBN: 81-7036565-1 (India-hb) &8039-9330-7 (US-hb) Sage Production Editor: Sumitra Srinivasan Contents List of Tables List of Figures Preface 1. Introduction: Scientific Communities in the Developing World Jacques Gaillard, V.V. Krishna and Roland Waast Part 1: Scientific Communities in Africa 2. Sisyphus or the Scientific Communities of Algeria Ali El Kenz and Roland Waast 3. -

Co-Opting Identity: the Manipulation of Berberism, the Frustration of Democratisation, and the Generation of Violence in Algeria Hugh Roberts DESTIN, LSE

1 crisis states programme development research centre www Working Paper no.7 CO-OPTING IDENTITY: THE MANIPULATION OF BERBERISM, THE FRUSTRATION OF DEMOCRATISATION AND THE GENERATION OF VIOLENCE IN LGERIA A Hugh Roberts Development Research Centre LSE December 2001 Copyright © Hugh Roberts, 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Programme Working papers series no.1 English version: Spanish version: ISSN 1740-5807 (print) ISSN 1740-5823 (print) ISSN 1740-5815 (on-line) ISSN 1740-5831 (on-line) 1 Crisis States Programme Co-opting Identity: The manipulation of Berberism, the frustration of democratisation, and the generation of violence in Algeria Hugh Roberts DESTIN, LSE Acknowledgements This working paper is a revised and extended version of a paper originally entitled ‘Much Ado about Identity: the political manipulation of Berberism and the crisis of the Algerian state, 1980-1992’ presented to a seminar on Cultural Identity and Politics organized by the Department of Political Science and the Institute for International Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, in April 1996. Subsequent versions of the paper were presented to a conference on North Africa at Binghamton University (SUNY), Binghamton, NY, under the title 'Berber politics and Berberist ideology in Algeria', in April 1998 and to a staff seminar of the Government Department at the London School of Economics, under the title ‘Co-opting identity: the political manipulation of Berberism and the frustration of democratisation in Algeria’, in February 2000. -

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

YVES CONGAR's THEOLOGY of LAITY and MINISTRIES and ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION in the UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to Th

YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Alan D. Mostrom UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2018 YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. APPROVED BY: ___________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ___________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Timothy R. Gabrielli, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader, Seton Hill University ___________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ William H. Johnston, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Alan D. Mostrom All rights reserved 2018 iii ABSTRACT YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. Yves Congar’s theology of the laity and ministries is unified on the basis of his adaptation of Christ’s triplex munera to the laity and his specification of ministry as one aspect of the laity’s participation in Christ’s triplex munera. The seminal insight of Congar’s adaptation of the triplex munera is illumined by situating his work within his historical and ecclesiological context. The U.S. reception of Congar’s work on the laity and ministries, however, evinces that Congar’s principle insight has received a mixed reception by Catholic theologians in the United States due to their own historical context as well as their specific constructive theological concerns over the laity’s secularity, or the priority given to lay ministry over the notion of a laity. -

US Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay

NAVAL AIR STATION KANEOHE, ADMINISTRATION AND HABS Hl-311-P OPERATIONS BUILDING HABS H/-311-P (U.S. Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, Facility 215) E Street between 3rd and 4th streets Kq1n,@0t1e Honolulu County Hawaii PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY U.S. NAVAL AIR STATION KANEOHE, OAHU, ADMINISTRATION AND OPERATIONS BUILDING (U.S. Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, Facility 215) HABS No. Hl-311-P Location: Honolulu County, Hawaii U.S.G.S. Mokapu Point quadrangle, 1998 7.5 Minute Series (Topographic) (Scale - 1 :24,000) NAD83 datum. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 04.628510.2371690. Lat./ Long. Coordinates: 21 °26'35.05" N 157°45'35.45" W Date of Construction: 1941 Designer: Albert Kahn, Inc., Detroit, Michigan Builder: Contractors, Pacific Naval Air Bases Owner: U.S. Marine Corps Present Use: Offices Significance: Facility 215, Administration and Operations Building, is significant for its association with U.S. Naval Air Station (NAS) Kaneohe and its role before the onset of World War II (WWII) in the Pacific. It was one of the primary buildings during the establishment of the U.S. Naval Air Station Kaneohe and headquarters for the station coll1111ander. The building contained the offices for numerous important administrative and coll1111unication functions of the station. The ca. 1939 building is also significant as a part of the original design of the station. In addition, Facility 215 at Kaneohe, along with forty-three other facilities there, is significant because it embodies distinctive characteristics of building types in this period that were designed by the notable architectural firm of Albert Kahn, Inc. -

Mecca of Revolution Oxford Studies in International History

Mecca of Revolution Oxford Studies in International History James J. Sheehan, series advisor The Wilsonian Moment Self- Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism Erez Manela In War’s Wake Europe’s Displaced Persons in the Postwar Order Gerard Daniel Cohen Grounds of Judgment Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth- Century China and Japan Pär Kristoffer Cassel The Acadian Diaspora An Eighteenth- Century History Christopher Hodson Gordian Knot Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order Ryan Irwin The Global Offensive The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post– Cold War Order Paul Thomas Chamberlin Mecca of Revolution Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order Jeffrey James Byrne Mecca of Revolution Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order JEFFREY JAMES BYRNE 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

MS 262 Papers of Aaron Zakharovich Steinberg (1891-1975), 1910-93

1 MS 262 Papers of Aaron Zakharovich Steinberg (1891-1975), 1910-93 1 Personal correspondence and papers 1/1 Personal correspondence of Steinberg; postcards; typescript of 1944, 1960-1, `Simon Dubnow, the man': an address by Steinberg for the Jewish n.d. Historical Society of England 1/2 Personal correspondence of Steinberg, mainly in Russian 1948-63 1/3 Copy of the last will of Steinberg 1 Jul 1966 1/4 Photograph of a family group; newspaper cutting, in Hebrew, c.1935-62 1935; sketch of Steinberg, 1962; typescript of the first part of `Erstes Buch das Zeitalter der ersten Emanzipation'; booklet Die Chassidus-Chabad-Lehre; booklet John Philipp 1/5 Notebook listing bibliographical details n.d. post 1962 1/6 Obituaries for Steinberg; circulars from Josef Fraenkel announcing 1975 the death of Steinberg and details of the funeral 1/7 In memoriam booklet for Steinberg; correspondence relating to 1975-7 Steinberg; copies of obituaries 1/8 Isaac Nachman Steinberg memorial book, in Yiddish (New York) 1961 1/9 Typescript papers in Russian; lists of names and addresses to 1968, n.d. whom Aaron Steinberg's memorial volume should be sent 1/10 Trees in Israel certificate that an avenue of eighty trees have been 1971 planted in honour of Steinberg on his eightieth birthday 2 General correspondence and papers 2/1 Foreign Compensation Commission: correspondence; statutory 1952, 1969-72 instrument, 1969; application forms of Steinberg with supporting sworn affidavit by his cousin M.Elyashev; copies of Les Juifs dans la Catechèse Chrétienne by Paul Demann -

LSTA Grant Lesson Plan Writing Cohort Submitted by Rebecca Griffith, Isaac Bear Early College High School

William Madison Randall Library LSTA Grant Lesson Plan Writing Cohort Submitted by Rebecca Griffith, Isaac Bear Early College High School Overview Abstract Examine the work performed by the women and teenagers of the Women’s Good Will Committee of High Point, North Carolina as they labor to bridge race relations in their community. Explore primary source documents using close reading strategies. Discover how the work of the High Point Women’s Good Will Committee serves as a positive model for other groups to replicate. Extrapolate and apply the work of the High Point Women’s Good Will Committee to a current societal ill and seek areas in which adults and students can cooperatively find solutions to these problems. Standards AH2.H.4 – Analyze how conflict and compromise have shaped politics, economics and culture in the United States. AH2.H.5 – Understand how tensions between freedom, equality and power have shaped the political, economic and social development of the United States. AH2.H.7 – Understand the impact of war on American politics, economics, society and culture. Objectives AH2.H.4.1 – Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted (e.g., Populism, Progressivism, working conditions and labor unrest, New Deal, Wilmington Race Riots, Eugenics, Civil Rights Movement, Anti-War protests, Watergate, etc.). AH2.H.4.3 – Analyze the social and religious conflicts, movements and reforms that impacted the United States since Reconstruction in terms of participants, strategies, opposition, and results (e.g., Prohibition, Social Darwinism, Eugenics, civil rights, anti-war protest, etc.). -

Heinonline (PDF)

Citation: 99 Va. L. Rev. 917 2013 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Thu Jul 31 13:28:08 2014 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0042-6601 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 99 SEPTEMBER 2013 NUMBER 5 ARTICLES AGAINST RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONALISM Richard Schragger*and Micah Schwartzman** INTRODUCTION .................................................. 918 I. THE NEw RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONALISM .................... 922 A. Corporatism ........................... ...... 922 B. Neo-Medievalism .................................. 926 II. FOUR OBJECTIONS TO RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONALISM ..... ...... 932 A. Selective History ........................ ...... 932 B. Anti-Republican ........................................ 939 C. Unlimited Scope ..................................... 945 D. Not Unique.. ................................. 949 III. CHURCHES AS VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS .......... ......... 956 A. Voluntarism. ................................. 957 B. Deriving CorporateRights ............. ................ 962 C. Is Religion Special? ..................... ....... 967 IV. TOWARDS A GENERAL THEORY OF CONSCIENTIOUS -

Country Report 2020

Algeria Country Trade Market Research & Industry Analysis Report November 2020 Agenda 01 Country Profile 02 Ease of Doing business 03 Economy ▪ General information ▪ IFC Indicators ▪ Infrastructure ▪ Consumption & income ▪ Economic Indices 04 Trade 05 Risk Assessment ▪ Trade Indicators ▪ Trade with world ▪ Trade with Abu Dhabi ▪ Target Sectors 2 1. COUNTRY PROFILE 3 1.1 GENERAL INFORMATION 4 General information about Algeria ▪ Capital Algiers ▪ Official language Arabic ▪ Population 2019 43,053,054 ▪ Population density 18.41 people per sq km ▪ GDP 2019 US$170.9B ▪ GDP per capita 2019 US$3,970.02 ▪ Income tax 35.0% ▪ Corporate tax 23.0% ▪ Currency Algerian dinar ▪ Exchange rate USD/DZD=119.35 ▪ Time zone UTC +01:00 Algeria is bounded to the east by Tunisia and Libya; to the south by Niger, Mali, and Mauritania; to the west by Morocco and Western Sahara (which has been virtually incorporated by the former); and ▪ VAT 19.0% to the north by the Mediterranean Sea. The southern 80 percent of Algeria's land is in the Sahara ▪ Average applied tariff rate 9.4% Desert and almost completely uninhabited. The northern half of the desert is less arid than the southern half, and most of the region's oases (any fertile tract in the midst of a wasteland) are found here. 5 Source: Avalara, PWC, index of economic freedom, export.gov, santander trade With a population of 2.8 million, Algiers is the largest urban area in Algeria Population in major urban areas in millions Land use in % of total area 2.8 Arable land Forest area Permanent cropland Other 0.9 0.8% 95.6% 3.1% 0.4% Algiers Oran The current population of Algeria is 44.14 million people 3.1% of Algeria's area is used as arable land, 0.8% is forest and based on projections of the latest United Nations data. -

Louis I. Kahn's Reading of Volume Zero Stanford Anderson

Public Institutions: Louis I. Kahn's Reading of Volume Zero Stanford Anderson Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), Vol. 49, No. 1. (Sep., 1995), pp. 10-21. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=1046-4883%28199509%2949%3A1%3C10%3APILIKR%3E2.0.CO%3B2-N Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) is currently published by Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Inc.. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/acsa.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to and preserving a digital archive of scholarly journals. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Wed May 16 23:15:41 2007 Public Institutions: Louis I. Kahn's Reading of Volume Zero STANFORDANDERSON, Massachusetts Institute of Technology In the work of architects like Louis I. Kahn or Volume Zero as a Temporal Concept but I never read anything but the first vol- Frank Lloyd Wright, we discover imagination and ume. -

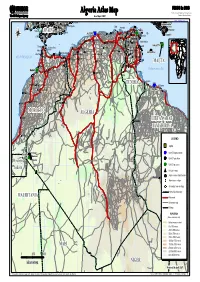

Algeria Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services

FICSS in DOS Algeria Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services ((( ((( ((( ((( Email : [email protected] ((( ((( ((( ((((( (((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( !!((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( !! La Unión ((( ((( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((((((((((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( C((((((a(((((tenanuova ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (Sciacca(( (((((( ((( ((!(! ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Baza (((((( ((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((((((((( ((( CaltanissettaCaltanissetta ((( ((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((((((((( (((((( Caltanissetta(Caltanissetta(( ((( ((( (((!!(((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((((((Sevilla((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((((( (((((( ((((( ((( ((( ((( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Cartagena ((( ((((( (((((((((((( ((( ((( ((( ((((((((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( Collo (((((( (((((( (((((( (Carlentini(( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((!! Annaba ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( !! Granada ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Licata((( !! (((((( ((( ((( ((( !! (((((( ((( ((( ((( SiracusaSiracusa ((( ((( TUNISTUNIS ((((((((( SiracusaSiracusa Huelva ((( ((( ((( TUNISTUNIS (((((((((Cómiso(((((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( !! (((((( ((( ((( (((((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAIN(SPAIN(( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAIN ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( ((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( ((( (((!! ((( Tebourba ((( ((( ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( (((!! ((( ((( ((( SPAINSPAIN((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( (((!! Almería ((( Jijel ((( ((( ((( ((((((