Exhibit List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equitable Allowances Or Restitutionary Measures for Dishonest Assistance and Knowing Receipt

Whayman D. Equitable allowances or restitutionary measures for dishonest assistance and knowing receipt. Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly 2017, 68(2), 181–202. Copyright: © Queen's University School of Law. This is the final version of an article published in Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly by Queen's University School of Law. DOI link to article: https://nilq.qub.ac.uk/index.php/nilq/article/view/34 Date deposited: 10/08/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk NILQ 68(2): 181–202 Equitable allowances or restitutionary measures for dishonest assistance and knowing receipt DEREK WHAYMAN * Lecturer in Law, Newcastle University Abstract This article considers the credit given to dishonest assistants and knowing recipients in claims for disgorgement, with greater focus on dishonest assistance. Traditionally, equity has awarded a parsimonious ‘just allowance’ for work and skill. The language of causation in Novoship (UK) Ltd v Mikhaylyuk [2014] EWCA Civ 908 suggests a more generous restitutionary approach which is at odds with the justification given: prophylaxis. This tension makes the law incoherent. Moreover, the bar to full disgorgement has been set too high, such that the remedy is unavailable in practice. Therefore, even if the restitutionary approach is affirmed, it must be revised. Keywords: disgorgement; equitable allowances; remoteness of gain; dishonest assistance; knowing receipt. isgorgement in equity has become more widely available. It is familiar as against a fiduciary where the profits of the defaulting fiduciary’s efforts are appropriated to the pDrincipal, seen in cases such as Boardman v Phipps .1 In Novoship (UK) Ltd v Mikhaylyuk , the Court of Appeal held that disgorgement is available in principle against accessories (meaning dishonest assistants and knowing recipients) to a breach of fiduciary duty. -

III. KNOWING Assistance .. ·I·

WHEN IS A STRANGERA CONSTRUCTIVETRUSTEE? 453 WHEN IS A STRANGER A CONSTRUCTIVE TRUSTEE? A CRITIQUE OF RECENT DECISIONS SUSAN BARKEHALL THOMAS• 1his articleexplores the conceptualdevelopment of Cet article explore le developpementconceptuel de third party liabilityfor participation in a breach of responsabilite civile dans la participation a fiduciary duty. 1he authorprovides a criticalanalysis l'inexecution d'une obligationfiduciaire. L 'auteur of thefoundations of third party liability in Canada fournit une analyse critique des fondations de la and chronicles the evolution of context-specific responsabilitecivile au Canada et decrit /'evolution liability tests. In particular, the testsfor the liability d'essais de responsabilites particulieres a une of banks and directorsare developed in their specific situation.Les essais de responsabilitedes banques el contexts. 1he author then provides a reasoned des adminislrateurssont particulierementdeveloppes critique of the Supreme Court of Canada's recent dans leur contexte precis. L 'auteurfournit ensulte trend towards context-independenttests. 1he author une critique raisonnee de la recente tendance de la concludes by arguing that the current approach is Cour supreme du Canada pour /es essais inadequateand results in an incoherentframework independantset particuliersa une situation.L 'auteur for the law of third party liability in Canada. conclut en pretendant que la demarche actuelle est inadequateet entraine un cadre incoherentpour la loi sur la responsabilitecivile au Canada. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN1R0DUCTION . • • • • . • . • . 453 II. KNOWING PARTICIPATION ......••...........•....•..... 457 A. BANKCASES . 457 B. APPLICATIONOF TIIE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST .....•...... 459 C. CONCEPTUALPROBLEMS Wl11I THE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST • . • . • • • . • . • . • . 463 D. CONCLUSIONSFROM PART II . 467 III. KNOWING AsSISTANCE .. ·I·............................ 467 A. THEAIR CANADA DECISION . • • • . • . 468 IV. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX accounts of profits, 54–5, 169 limitation statutes, 84–5 remedies for. See remedies allowances, 57–8 unclean hands, 86–8, 168 for breach of trust breach of confidence, 197 beneficiaries, 206 ‘but for’ test, 65–6, 333 calculation of, 55–7 administration of trust and, acquiescence, 85–6 207 calculation of equitable as equitable defence to creditors’ rights and, 313–14 compensation, 60–1 breach of trust, 329–30 differences between fixed breach of fiduciary duty, overlap with laches, 85–6 and discretionary trusts 63–5 advancement for, 207 breach of trust, 61–3 presumption of, 357–9 ‘gift-over’ right, 208–9 calculation of equitable agency indemnification of trustees, damages trusts and, 210–11 311–13 causation standard, 65–6 aggravated damages, 68 interest, trustees’ right to common law adjustments to Anton Piller order, 39 impound, 314 quantum, 66–8 Aristotle, 4 investment of trust funds, categories of constructive trusts, assessment of equitable 297, 299 371 damages, 51 ‘list certainty’, 227 as remedy to proprietary in addition to injunction or sui juris, 278, 312 estoppel, 380–2 specific performance, 51 trust property and, 208 as restitutionary remedy in substitution for injunction trustees’ right to recover for unjust enrichment, or specific performance, overpayment from, 315 380–2 51–2 breach of confidence, 17–18, 47, Baumgartner constructive assignments 50, 68 trusts, 375–9 equitable property, 138–9 defences to. See defences to common intention, family future property, 137–8 breach of confidence property disputes and, gifts, 133–6 remedies for. -

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers A. Introduction 1. This paper supports and provides the references for the Wonderland Ltd case study1 which will be considered during the seminar. 2. The aim of the case study is to explore claims which go beyond the usual fare of the office- holder’s statutory remedies by way of transactions at an undervalue, preference, s. 212 misfeasance claims, wrongful or fraudulent trading or transactions defrauding creditors. Instead we explore claims against third parties, where there has been a breach of the Companies Act and/or breach of fiduciary duty by directors, unlawful dividends being used as an example. B. Dividends 3. There are usually 3 potential grounds for challenging dividend payments: 3.1. the conventional technical claim made under the Companies legislation that dividends have not been paid out of profits available for that purpose and that the dividends have been paid in breach of the Companies legislation; 3.2. that the internal regulations of the company were breached and/or 3.3. breach of the common law maintenance of capital rule. We consider these in turn. B1 Part VIII CA 1985 4. In the case study the dividends were paid between 1 Sep 2007 and 1 March 2008. The relevant law is therefore Part VIII Companies Act 1985 (ss. 263 – 281 CA 1985)2. 5. A distribution of a company’s assets (which includes a dividend) can only be made out of profits available for the purpose (s. 263(1) CA 1985)3 being its accumulated, realised profits, so far as not previously utilised by distribution or capitalisation, less its accumulated, realised losses, so far as not previously written off in a reduction or reorganisation of capital duly made (s. -

1/1 DIRECTOR and OFFICER LIABILITY in the ZONE of INSOLVENCY: a COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak Summary It Is the Duty of the Dire

HH RAJAK (SUMMARY) PER/PELJ 2008(11)1 DIRECTOR AND OFFICER LIABILITY IN THE ZONE OF INSOLVENCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak* Summary It is the duty of the directors of a company to run the business of the company in the best interests of the company and its shareholders. In principle, the company, alone, is responsible for the debts incurred in the running of the company and the creditors are, in principle, precluded from looking to the directors or shareholders for payment of any shortfall arising as a result of the company's insolvency. This principle has, in a number of jurisdictions undergone statutory change such that in certain circumstances, the directors and others who were concerned with the management of the company may be made liable to contribute, personally, to meet the payment – in part or entirely – of the company's debts. This paper aims to explore this statutory jurisdiction. It also seeks to describe succinctly the process by which the shift from unlimited to limited liability trading was achieved. It will end by examining briefly a comparatively new phenomenon, namely that of a shift in the focus of the directors' duties from company and shareholders to the creditors as the company becomes insolvent and nears the stage of a formal declaration of its insolvent status – the so-called 'zone of insolvency'. * Prof Harry Rajak. Professor Emeritus, Sussex Law School, University of Sussex. 1/1 DIRECTOR AND OFFICER LIABILITY IN THE ZONE OF INSOLVENCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS ISSN 1727-3781 2008 VOLUME 11 NO 1 HH RAJAK PER/PELJ 2008(11)1 DIRECTOR AND OFFICER LIABILITY IN THE ZONE OF INSOLVENCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak* 1 Introduction It is a generally accepted proposition that the duty of the directors of a company is to run the business of the company in the best interests of the company. -

Directors' Duties and Liabilities in Financial Distress During Covid-19

Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 July 2020 allenovery.com Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 A global perspective Uncertain times give rise to many questions Many directors are uncertain about their responsibilities and the liability risks The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic in these circumstances. They are facing questions such as: crisis has a significant impact, both financial and – If the company has limited financial means, is it allowed to pay critical suppliers and otherwise, on companies around the world. leave other creditors as yet unpaid? Are there personal liability risks for ‘creditor stretching’? – Can you enter into new contracts if it is increasingly uncertain that the company Boards are struggling to ensure survival in the will be able to meet its obligations? short term and preserve cash, whilst planning – Can directors be held liable as ‘shadow directors’ by influencing the policy of subsidiaries for the future, in a world full of uncertainties. in other jurisdictions? – What is the ‘tipping point’ where the board must let creditor interest take precedence over creating and preserving shareholder value? – What happens to intragroup receivables subordinated in the face of financial difficulties? – At what stage must the board consult its shareholders in case of financial distress and does it have a duty to file for insolvency protection? – Do special laws apply in the face of Covid-19 that suspend, mitigate or, to the contrary, aggravate directors’ duties and liability risks? 2 Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 | July 2020 allenovery.com There are more jurisdictions involved than you think Guidance to navigating these risks Most directors are generally aware of their duties under the governing laws of the country We have put together an overview of the main issues facing directors in financially uncertain from which the company is run. -

![[2010] EWCA Civ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5628/2010-ewca-civ-645628.webp)

[2010] EWCA Civ

Neutral Citation Number: [2010] EWCA Civ 895 Case No: A2/2009/1942 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CHANCERY DIVISION (COMPANIES COURT) MR NICHOLAS STRAUSS QC (SITTING AS A DEPUTY JUDGE OF THE CHANCERY DIVISION) Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 30th July 2010 Before: LORD JUSTICE WARD LORD JUSTICE WILSON and MR JUSTICE HENDERSON - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: (1) David Rubin (2) Henry Lan (Joint Receivers and Managers of The Consumers Trust) Appellants - and - (1) Eurofinance SA (2) Adrian Roman (3) Justin Roman (4) Nicholas Roman Respondents (Transcript of the Handed Down Judgment of WordWave International Limited A Merrill Communications Company 165 Fleet Street, London EC4A 2DY Tel No: 020 7404 1400, Fax No: 020 7404 1424 Official Shorthand Writers to the Court) Tom Smith (instructed by Dundas & Wilson LLP) for the appellant Marcus Staff (instructed by Brown Rudnick LLP) for the respondent Hearing dates: 27 and 28th January 2010 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment As Approved by the Court Crown copyright© See: permission to appeal and a stay of execution (at bottom) Lord Justice Ward: The issues 1. As the issues have been refined in this Court, there are now essentially two questions for our determination: (1) should foreign bankruptcy proceedings, here Chapter 11 proceedings in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, including the Adversary Proceedings, be recognised as a foreign main proceeding in accordance with the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (“the Model Law”) as set out in schedule 1 to the Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations 2006 (“the Regulations”) and the appointment therein of the appellants, Mr David Rubin and Mr Henry Lan, as foreign representatives within the meaning of Article 2(j) of the Model Law be similarly recognised; and (2) should the judgment or parts of the judgment of the U.S. -

International Dimensions of Japanese Insolvency Law

MONETARY AND ECONOMIC STUDIES/FEBRUARY 2001 International Dimensions of Japanese Insolvency Law Raj Bhala This paper offers an introduction and overview of the international aspects of Japanese insolvency law. There are three international dimensions to Japan’s insolvency law: jurisdiction of Japanese courts; the status of foreign claimants; and recognition and enforcement of foreign proceedings. These dimensions are characterized by a distinctly territorial approach. This inward-looking way of handling insolvency cases is incongruous with developments in the comparative and international law context. It is also at odds with broader globalization trends, some of which are evident in Japan’s economic crisis. Analogies to international trade law are useful: the post-Uruguay Round dispute resolution mechanism has insights for the problem of jurisdiction; the famous national treatment principle is a basis for critiquing the status foreign claimants have in Japanese insolvency proceedings; and trade negotiations might be a model for expanding recognition and enforcement of foreign proceedings. As a corollary, the relationship between the extant insolvency regime and Japanese banks— many of which are internationally active—is explored. Problem banks are at the heart of the economic crisis. Yet, the insolvency law regime has not been applied to failed or failing banks, partly on grounds of the systemic risk that would be triggered by a stay of creditor proceedings. The reluctance to use the regime in bank cases is open to question on a number of grounds. Similarly, the failure to develop a harmonized set of international bank bankruptcy rules to avoid BCCI-type liquidation problems is addressed, and a proposal for proceeding in this direction is offered. -

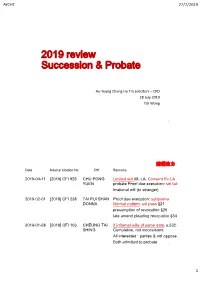

2019 Review Succession & Probate

AYCHT 27/7/2019 2019 review Succession & Probate Au‐Yeung Cheng Ho Tin solicitors –CPD 28 July 2019 Tak Wong 1 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2019-04-11 [2019] CFI 925 CHU PONG Limited will 08, LA. Consent Rv LA YUEN probate Proof due execution: sol fail Irrational will (to stranger) 2019-02-01 [2019] CFI 238 TAI PUI SHAN Proof due execution: subpoena. DONNA Normal pattern. sol pass §21 presumption of revocation §26 late amend pleading revocation §34 2019-01-28 [2019] CFI 103 CHEUNG TAI 2 informal wills of same date. s.5(2) SHING Cumulative, not inconsistent. All interested : parties & not oppose. Both admitted to probate. 2 1 AYCHT 27/7/2019 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-12-19 [2018] CFA 61 CHOY PO B v G evidence 3 limbs T/C.gap§11 CHUN fact-specific. No proper basis will instruction §18. will invalid 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING Same B v G 3 limbs T/C. CHUNG fact-specific Yes proper basis. Choy Po Chun distinguished. Will instruction direct / rational Sol > sol firm. Will valid. 3 親屬關係 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-08-08 [2018] CA 491 LI CHEONG Natural dau, 1. DNA 2. copy B/C, rolled-up hearing directions 2018-10-18 [2018] CA 719 LI CHEONG Probate action in rem nature, O.15 r.13A, intended intervener, dismiss 2014-07-03 MOK HING CCL:spinster 1.no adopt §89 2.yes CHUNG i-tze 3.yes IEO s2(2)(c) 4.DWAE案 2018-10-19 [2018] CA 713 MOK HING CCL adoption v i-tze, apply to file CHUNG obituary notice, Ladd, dismiss 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING CCL no formalities (adoption/i-tze) CHUNG §52, all 7 appeal grounds no merit. -

Unconscionability As an Underlying Concept in Equity

THE DENNING LAW JOURNAL UNCONSCIONABILITY AS A UNIFYING CONCEPT IN EQUITY Mark Pawlowski* ABSTRACT This article seeks to examine the extent to which a unified concept of unconscionability can be used to rationalise related doctrines of equity, in particular, in the areas of (1) unconscionable bargains, undue influence and duress (2) proprietary estoppel (3) knowing receipt liability and (4) relief against forfeitures. The conclusion is that such a process of amalgamation may provide a principled doctrinal basis for equity’s intervention which has already found favour in the English courts. INTRODUCTION A recent discernible trend in equity has been the willingness of the English courts to adopt a broader-based doctrine of unconscionability as underlying proprietary estoppel claims and the personal liability of a stranger to a trust who has knowingly received trust property in breach of trust. The decisions in Gillett v Holt,1 Jennings v Rice2 and Campbell v Griffin3 in the context of proprietary estoppel and Bank of Credit and Commerce International (Overseas) Ltd v Akindele4 on the subject of receipt liability, demonstrate the judiciary’s growing recognition that the concept of unconscionability provides a useful mechanism for affording equitable relief against the strict insistence on legal rights or unfair and oppressive conduct. This, in turn, prompts the question whether there are other areas which would benefit from a rationalisation of principles under the one umbrella of unconscionability. The process of amalgamation, it is submitted, would be particularly useful in areas where there are currently several related (but distinct) doctrines operating together so as to give rise to confusion and overlap in the same field of law. -

Unit 5 – Equity and Trusts Suggested Answers - January 2013

LEVEL 6 - UNIT 5 – EQUITY AND TRUSTS SUGGESTED ANSWERS - JANUARY 2013 Note to Candidates and Tutors: The purpose of the suggested answers is to provide students and tutors with guidance as to the key points students should have included in their answers to the January 2013 examinations. The suggested answers set out a response that a good (merit/distinction) candidate would have provided. The suggested answers do not for all questions set out all the points which students may have included in their responses to the questions. Students will have received credit, where applicable, for other points not addressed by the suggested answers. Students and tutors should review the suggested answers in conjunction with the question papers and the Chief Examiners’ reports which provide feedback on student performance in the examination. SECTION A Question 1 This essay will examine the general characteristics of equitable remedies before examining each remedy in turn to analyse whether they are in fact strict and of limited flexibility as the question suggests. The best way to examine the general characteristics of equitable remedies is to draw comparisons with the common law. Equitable remedies are, of course discretionary, whereas the common law remedy of damages is available as of right. This does not mean that the court has absolute discretion, there are clear principles which govern the grant of equitable remedies. Equitable remedies are granted where the common law remedies would be inadequate or where the common law remedies are not available because the right is exclusively equitable. One of the key characteristics of equitable remedies is of course that they act in personam. -

What Does the Temporary Relief from Wrongful Trading Tell Us About Singapore’S New Insolvency Law Regime? Stacey Steele*

Asian Legal Conversations — COVID-19 Asian Law Centre Melbourne Law School Insolvency Law Responses to COVID-19: What does the Temporary Relief from Wrongful Trading Tell Us about Singapore’s New Insolvency Law Regime? Stacey Steele* The Singapore Government introduced temporary measures to relieve officers from new wrongful trading provisions as part of its response to COVID-19 in April 2020. The provisions establishing liability for wrongful trading are set out in the Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Act 2018 (Singapore) (the “IRDA”) – which is yet to become effective. Singapore’s measures are in line with the position taken by many other jurisdictions, but they come at a time when the IRDA provisions aren’t even operative. This post asks, “what does this temporary relief from wrongful trading liability tell us about Singapore’s new insolvency law regime?” New wrongful trading provisions in the IRDA Singapore’s existing fraudulent and insolvent trading provisions were substantially reformed and a new liability for wrongful trading was introduced in 2018 by the IRDA as part of a package of reforms to strengthen Singapore’s status as an international hub for debt restructuring. Under section 239(1) of the IRDA: If, in the course of the judicial management or winding up of a company or in any proceedings against a company, it appears that the company has traded wrongfully, the Court… may… declare that any person who was a party to the company trading in that manner is personally responsible… for all or any of the debts or other liabilities of the company as the Court directs, if that person: • knew that the company was trading wrongfully; or • as an officer of the company, ought, in all the circumstances, to have known that the company was trading wrongfully.