International Dimensions of Japanese Insolvency Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1/1 DIRECTOR and OFFICER LIABILITY in the ZONE of INSOLVENCY: a COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak Summary It Is the Duty of the Dire

HH RAJAK (SUMMARY) PER/PELJ 2008(11)1 DIRECTOR AND OFFICER LIABILITY IN THE ZONE OF INSOLVENCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak* Summary It is the duty of the directors of a company to run the business of the company in the best interests of the company and its shareholders. In principle, the company, alone, is responsible for the debts incurred in the running of the company and the creditors are, in principle, precluded from looking to the directors or shareholders for payment of any shortfall arising as a result of the company's insolvency. This principle has, in a number of jurisdictions undergone statutory change such that in certain circumstances, the directors and others who were concerned with the management of the company may be made liable to contribute, personally, to meet the payment – in part or entirely – of the company's debts. This paper aims to explore this statutory jurisdiction. It also seeks to describe succinctly the process by which the shift from unlimited to limited liability trading was achieved. It will end by examining briefly a comparatively new phenomenon, namely that of a shift in the focus of the directors' duties from company and shareholders to the creditors as the company becomes insolvent and nears the stage of a formal declaration of its insolvent status – the so-called 'zone of insolvency'. * Prof Harry Rajak. Professor Emeritus, Sussex Law School, University of Sussex. 1/1 DIRECTOR AND OFFICER LIABILITY IN THE ZONE OF INSOLVENCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS ISSN 1727-3781 2008 VOLUME 11 NO 1 HH RAJAK PER/PELJ 2008(11)1 DIRECTOR AND OFFICER LIABILITY IN THE ZONE OF INSOLVENCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak* 1 Introduction It is a generally accepted proposition that the duty of the directors of a company is to run the business of the company in the best interests of the company. -

Directors' Duties and Liabilities in Financial Distress During Covid-19

Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 July 2020 allenovery.com Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 A global perspective Uncertain times give rise to many questions Many directors are uncertain about their responsibilities and the liability risks The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic in these circumstances. They are facing questions such as: crisis has a significant impact, both financial and – If the company has limited financial means, is it allowed to pay critical suppliers and otherwise, on companies around the world. leave other creditors as yet unpaid? Are there personal liability risks for ‘creditor stretching’? – Can you enter into new contracts if it is increasingly uncertain that the company Boards are struggling to ensure survival in the will be able to meet its obligations? short term and preserve cash, whilst planning – Can directors be held liable as ‘shadow directors’ by influencing the policy of subsidiaries for the future, in a world full of uncertainties. in other jurisdictions? – What is the ‘tipping point’ where the board must let creditor interest take precedence over creating and preserving shareholder value? – What happens to intragroup receivables subordinated in the face of financial difficulties? – At what stage must the board consult its shareholders in case of financial distress and does it have a duty to file for insolvency protection? – Do special laws apply in the face of Covid-19 that suspend, mitigate or, to the contrary, aggravate directors’ duties and liability risks? 2 Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 | July 2020 allenovery.com There are more jurisdictions involved than you think Guidance to navigating these risks Most directors are generally aware of their duties under the governing laws of the country We have put together an overview of the main issues facing directors in financially uncertain from which the company is run. -

![[2010] EWCA Civ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5628/2010-ewca-civ-645628.webp)

[2010] EWCA Civ

Neutral Citation Number: [2010] EWCA Civ 895 Case No: A2/2009/1942 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CHANCERY DIVISION (COMPANIES COURT) MR NICHOLAS STRAUSS QC (SITTING AS A DEPUTY JUDGE OF THE CHANCERY DIVISION) Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 30th July 2010 Before: LORD JUSTICE WARD LORD JUSTICE WILSON and MR JUSTICE HENDERSON - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: (1) David Rubin (2) Henry Lan (Joint Receivers and Managers of The Consumers Trust) Appellants - and - (1) Eurofinance SA (2) Adrian Roman (3) Justin Roman (4) Nicholas Roman Respondents (Transcript of the Handed Down Judgment of WordWave International Limited A Merrill Communications Company 165 Fleet Street, London EC4A 2DY Tel No: 020 7404 1400, Fax No: 020 7404 1424 Official Shorthand Writers to the Court) Tom Smith (instructed by Dundas & Wilson LLP) for the appellant Marcus Staff (instructed by Brown Rudnick LLP) for the respondent Hearing dates: 27 and 28th January 2010 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment As Approved by the Court Crown copyright© See: permission to appeal and a stay of execution (at bottom) Lord Justice Ward: The issues 1. As the issues have been refined in this Court, there are now essentially two questions for our determination: (1) should foreign bankruptcy proceedings, here Chapter 11 proceedings in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, including the Adversary Proceedings, be recognised as a foreign main proceeding in accordance with the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (“the Model Law”) as set out in schedule 1 to the Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations 2006 (“the Regulations”) and the appointment therein of the appellants, Mr David Rubin and Mr Henry Lan, as foreign representatives within the meaning of Article 2(j) of the Model Law be similarly recognised; and (2) should the judgment or parts of the judgment of the U.S. -

What Does the Temporary Relief from Wrongful Trading Tell Us About Singapore’S New Insolvency Law Regime? Stacey Steele*

Asian Legal Conversations — COVID-19 Asian Law Centre Melbourne Law School Insolvency Law Responses to COVID-19: What does the Temporary Relief from Wrongful Trading Tell Us about Singapore’s New Insolvency Law Regime? Stacey Steele* The Singapore Government introduced temporary measures to relieve officers from new wrongful trading provisions as part of its response to COVID-19 in April 2020. The provisions establishing liability for wrongful trading are set out in the Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Act 2018 (Singapore) (the “IRDA”) – which is yet to become effective. Singapore’s measures are in line with the position taken by many other jurisdictions, but they come at a time when the IRDA provisions aren’t even operative. This post asks, “what does this temporary relief from wrongful trading liability tell us about Singapore’s new insolvency law regime?” New wrongful trading provisions in the IRDA Singapore’s existing fraudulent and insolvent trading provisions were substantially reformed and a new liability for wrongful trading was introduced in 2018 by the IRDA as part of a package of reforms to strengthen Singapore’s status as an international hub for debt restructuring. Under section 239(1) of the IRDA: If, in the course of the judicial management or winding up of a company or in any proceedings against a company, it appears that the company has traded wrongfully, the Court… may… declare that any person who was a party to the company trading in that manner is personally responsible… for all or any of the debts or other liabilities of the company as the Court directs, if that person: • knew that the company was trading wrongfully; or • as an officer of the company, ought, in all the circumstances, to have known that the company was trading wrongfully. -

An Introduction to Corporate Insolvency Law

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk The Plymouth Law & Criminal Justice Review The Plymouth Law & Criminal Justice Review, Volume 08 - 2016 2016 An Introduction to Corporate Insolvency Law Anderson, Hamish Anderson, H. (2016) 'An Introduction to Corporate Insolvency Law',Plymouth Law and Criminal Justice Review, 8, pp. 16-47. Available at: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/handle/10026.1/9038 http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/9038 The Plymouth Law & Criminal Justice Review University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Plymouth Law and Criminal Justice Review (2016) 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO CORPORATE INSOLVENCY LAW Hamish Anderson1 Abstract English law provides three forms of insolvency proceeding for companies: liquidation, administration and company voluntary arrangements. This paper begins by examining the nature and purpose of insolvency law, the concepts of insolvency and insolvency proceedings, how insolvency practice is regulated and the role of the court. It then considers the sources of the law before describing the distinguishing characteristics of liquidation, administration and company voluntary arrangements. Finally, it deals with the sanctions for malpractice, transaction avoidance and cross-border insolvency. Keywords: insolvency, liquidation, administration, company voluntary arrangement, office- holder, wrongful trading, fraudulent trading, director disqualification, transaction avoidance Introduction This paper is a high level introduction to corporate insolvency law for students of company law. -

Outline of Recent SEC Enforcement Actions

Outline of Recent SEC Enforcement Actions Submitted by: 1 Joan McKown Chief Counsel Prepared by: 2 Division of Enforcement U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 1 The Securities and Exchange Commission, as a matter of policy, disclaims responsibility for any private publication or statement by any of its employees. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission or its staff. 2 Parts of this outline have been used in other publications. Table of Contents CASES INVOLVING FINANCIAL FRAUD & OTHER DISCLOSURE AND REPORTING VIOLATIONS...................................................................................................................2 SEC v. Jacob Alexander, David Kreinberg, and William F. Sorin ...................................................................... 2 SEC v. MBIA Inc........................................................................................................................................................... 3 In the Matter of City of San Diego, California ......................................................................................................... 3 SEC v. Viper Capital Management, LLC, et al. ....................................................................................................... 4 SEC v. Michael Moran, James Sievers, Martin Zaepfel, James Cannataro, John Steele, Michael Crusemann and Michael Otto .............................................................................................................................. -

Global Restructuring & Insolvency Guide

Global Restructuring & Insolvency Guide Egypt Overview and Introduction As in other jurisdictions, the primary objective of the Egyptian insolvency and bankruptcy regulation (collectively, the “Insolvency and Bankruptcy Regulation”) is to protect and maximise the value of the bankrupt company for the benefit of all the creditors. The bankruptcy regulation was substantially overhauled and culminated in what was perceived to be a “more modern bankruptcy regime”, which came into operation on 1 October 1999. However, the Egyptian Insolvency and Bankruptcy Regulation remains lacking and requires an in-depth review. Indeed, various parts of the legislation need to be updated, and the relevant legislation requires further consolidation for easier understanding and application. Applicable Legislation The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Regulation in Egypt is scattered among the Civil Code of 1948, Companies Law No. 159 of 1981, and the bankruptcy rules under Trade Law No. 17 of 1999 ("Trade Law"). It is worth noting that Egyptian law differentiates between insolvency, which is regulated under the Civil Law, and bankruptcy, which is regulated under the Trade Law. In this respect, the Civil Law provides that a debtor may be declared insolvent if his assets are insufficient to pay his due debts. The insolvency rules, as regulated by the Civil Law, apply to non-traders with regards to non- commercial debts. Meanwhile, bankruptcy rules, as regulated by the Trade Law, apply to traders who, according to said law, are bound to hold commercial registers. According to the Trade Law, a trader shall be considered in the state of bankruptcy in the event he stops paying his commercial debts following disturbance of his financial business. -

What a Creditor Needs to Know About Liquidating an Insolvent Cayman

What a creditor needs to know about liquidating GUIDE an insolvent Cayman company Last reviewed: December 2020 Contents Introduction 3 When is a company insolvent? 3 What is a statutory demand? 3 Is it essential to serve a statutory demand? 3 What must a statutory demand say? 3 Setting aside a statutory demand 4 How may a company be put into liquidation? 4 Official liquidation 4 Provisional liquidation 4 Appointment of liquidator 5 Functions and powers of liquidators 5 Functions and powers of an official liquidator 5 Powers of a provisional liquidator 6 Court order 6 Who may apply? 6 Application 7 Debt should be undisputed 7 When does a company's liquidation start? 7 What are the consequences of a company being put into liquidation? 7 Automatic consequences 7 Restriction on execution and attachment 8 Public documents 8 Other consequences 8 Effect on contracts 8 How do creditors claim in a company's liquidation? 8 Making a claim 8 Currency 9 Contingent debts 9 Interest 9 Admitting or rejecting claims 9 What is a liquidation committee? 9 2021934/78537493/2 BVI | CAYMAN ISLANDS | GUERNSEY | HONG KONG | JERSEY | LONDON mourant.com Establishing the committee 9 Distributions 10 Pari passu principle 10 Excluded assets 10 Order of distribution 10 How are secured creditors affected by a company's liquidation? 10 General position 10 Liquidator challenge 10 Claiming in the liquidation 10 What are preferential debts? 11 Preferential debts 11 Priority 11 What are the claims of current and past shareholders? 11 Do shareholders have to contribute towards -

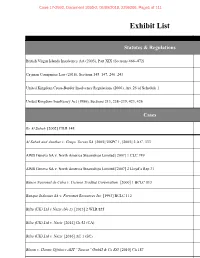

Exhibit List

Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page1 of 111 Exhibit List Statutes & Regulations British Virgin Islands Insolvency Act (2003), Part XIX (Sections 466–472) B Cayman Companies Law (2016), Sections 145–147, 240–243 United Kingdom Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations (2006), Art. 25 of Schedule 1 United Kingdom Insolvency Act (1986), Sections 213, 238–239, 423, 426 Cases Re Al Sabah [2002] CILR 148 Al Sabah and Another v. Grupo Torras SA [2005] UKPC 1, [2005] 2 A.C. 333 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 1 CLC 749 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 31 Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Cosmos Trading Corporation [2000] 1 BCLC 813 Banque Indosuez SA v. Ferromet Resources Inc [1993] BCLC 112 Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir (No 2) [2013] 2 WLR 825 Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2014] Ch 52 (CA) Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2016] AC 1 (SC) Bloom v. Harms Offshore AHT “Taurus” GmbH & Co KG [2010] Ch 187 Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page2 of 111 Exhibit List Cases, continued Re Paramount Airways Ltd [1993] Ch 223 Picard v. Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC BVIHCV140/2010 B Rubin v. Eurofinance SA [2013] 1 AC 236; [2012] UKSC 46 Singularis Holdings Ltd v. PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36, [2015] A.C. 1675 Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v. Krys [2015] AC 616; [2014] UKPC 41 Other Authorities McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation (4th ed. 2017) Anthony Smellie, A Cayman Islands Perspective on Trans-Border Insolvencies and Bankruptcies: The Case for Judicial Co-Operation , 2 Beijing L. -

Directors' Duties When a Company Is Facing Insolvency

Directors’ Duties when a Company is facing Insolvency 0 DIRECTORS’ DUTIES WHEN A COMPANY IS FACING INSOLVENCY Introduction It is well established that the fiduciary and statutory duties of directors are generally owed to the company. However, where a company is insolvent or is threatened with insolvency this fundamental principal changes; the duty to act in good faith and to show the utmost care, skill and diligence will become owed by the directors to the creditors. This does not mean that a company should close down at the first sight of economic difficulty. Although the directors may have no choice but to recommend placing the company in liquidation and distributing the assets for the benefit of the creditors, this may not always be the case. It may be that by trading forward, a more favourable outcome for creditors is achieved. Where it is reasonable to continue to trade, for example in an effort to complete a contract and generate further revenue, the directors will not necessarily be on the hook for reckless trading. This was recognized in Re: Hefferon Kearns Limited (No. 2)1, where the Court commented that “it would not be in the interests of the community that whenever there might be significant danger that a company was going to become insolvent, the directors should immediately cease trading and close down. Many businesses which might have well survived by continuing to trade coupled with remedial measures could be lost to the community”. However, continuing to trade with caution in times of difficulty should be contrasted with not winding up a company which has been shown to be insolvent and the principal reason for not winding it up is that the assets would be insufficient to cover the associated costs. -

1/36 DIRECTOR and OFFICER LIABILITY in the ZONE of INSOLVENCY: a COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak* 1 Introduction It Is a Generally

HH RAJAK PER 2008(1) DIRECTOR AND OFFICER LIABILITY IN THE ZONE OF INSOLVENCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS HH Rajak* 1 Introduction It is a generally accepted proposition that the duty of the directors of a company is to run the business of the company in the best interests of the company. Some, who are perhaps less pedantic about the separation in legal terms of the company from its shareholders, would extend the beneficiary of these duties to include the shareholders. Nevertheless, this separation is of crucial importance, in particular in shifting the primary liability for the debts incurred in running the business, from the individual entrepreneur, to the company which, in law, owns and carries on the business. The company is the primary debtor and the legal status of the entrepreneur is that of being a director of, and a shareholder with limited liability in, the company. Thus, in principle, the company, alone, is responsible for the debts incurred in the running of the company and the creditors are, in principle, precluded from looking to the entrepreneur for payment of any shortfall arising as a result of the company's insolvency. It is also the case that in a number of jurisdictions statutory changes have sought, in certain circumstances, to render the directors and others who were concerned with the management of the company prior to the insolvent liquidation, liable to contribute to the assets of the company so as to assist the insolvent estate in meeting the company's debts to its creditors. This paper aims to explore this statutory jurisdiction. -

Law & Practice: Doing Business In

UK LAW & PRACTICE: p.541 Contributed by Sullivan & Cromwell LLP The ‘Law & Practice’ sections provide easily accessible information on navigating the legal system when conducting business in the jurisdic- tion. Leading lawyers explain local law and practice at key transactional stages and for crucial aspects of doing business. DOING BUSINESS IN UK: p.585 Chambers & Partners employ a large team of full-time researchers (over 140) in their London office who interview thousands of clients each year. This section is based on these interviews. The advice in this section is based on the views of clients with in-depth international experience. Law & PracTicE UK Contributed by Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Author: Chris Howard Law & Practice Contributed by Sullivan & Cromwell LLP CONTENTS 1. Market Panorama p.545 8.2 Chief Restructuring Officer p.569 1.1 Market Dynamics p.545 8.3 Shadow Directorship p.570 2. Debt Trading p.547 9. Solvent Restructuring/Reorganisation and Rescue 2.1 Limitations on Non-Banks and Foreign Procedures p.570 Institutions p.547 9.1 Statutory Mechanisms p.570 2.2 Debt Trading Practice p.547 9.2 Position of Company During Procedure p.573 2.3 Loan Market Guidelines p.548 9.3 Position of Creditors During Procedure p.574 3. Informal and Consensual Restructuring Framework p.549 9.4 Claims of a Dissenting Class of Creditors p.574 3.1 Consensual Restructuring p.549 9.5 Trading Claims of Dissenting Creditors p.574 3.2 Consensual Restructuring Process p.551 9.6 Re-organising a Corporate Group p.574 3.3 New Money p.556 9.7 Conditions Applied to Use or Sale of Assets p.574 3.4 Duties of the Parties p.557 9.8 Distressed Disposals p.575 3.5 Consensually Agreed Restructuring p.558 9.9 Release of Security and Other Claims p.575 9.10 Priority p.575 4.