The Occupy Movement in Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

Dissenting Media in Post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip the De

Dissenting media in post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip The de-colonization of Hong Kong took the form of Britain returning the territory to China in 1997 as a Special Administrative Region (SAR). Twenty years after the political handover, the “one country, two systems” arrangement designed by China to govern the Hong Kong SAR is facing serious challenge: Many in Hong Kong have come to regard Beijing as an unwelcome control master; and calls for self-determination have gained a substantial level of popular support. This chapter examines the role of media in this development, as exemplified by key political protest actions. It proposes the notion of “dissenting media” as a framework to integrate relevant academic and journalistic studies about Hong Kong. From the discipline of media and communications study, it suggests that operators of dissenting media are enabled to put forth information and analysis contrary to that of the establishment, which, in turn, help to form an oppositional public sphere. In the process, the identity and communities of dissent are built, maintained, and developed, contributing to the formation of a counter public that participates in oppositional political actions. Studies on the impact of media, mainly conducted in stable Anglo-American societies, tend to consider mainstream media as institutions that index1 or reinforce the status quo,2 and alternative media as forces that challenge established powers.3 In Hong Kong, the 1997 political changeover was accompanied by a reconfiguration of power relationships in line with China’s one-party dictatorship. The change runs counter to the political aspirations of the people of Hong Kong, and has bred a political movement for civil liberties, public accountability, and democracy. -

Off-Campus Attractions, Restaurants and Shopping

Off-Campus Attractions, Restaurants and Shopping The places listed in this guide are within 30 – 35 minutes travel time via public transportation from HKU. The listing of malls and restaurants is suggested as a resource to visitors but does not reflect any endorsement of any particular establishment. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, you may check the website of the restaurant or mall for the most updated information. For additional information on getting around using public transports in Hong Kong, enter the origin and destination into the website: http://hketransport.gov.hk/?l=1&slat=0&slon=0&elat=0&elon=0&llon=12709638.92104&llat=2547711.355213 1&lz=14 or . For more information on discovering Hong Kong, please visit http://www.discoverhongkong.com/us/index.jsp or . Please visit https://www.openrice.com/en/hongkong or for more information on food and restaurants in Hong Kong. Man Mo Temple Address: 124-126 Hollywood Road, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong Island How to get there: MTR Sheung Wan Station Exit A2 then walk along Hillier Street to Queen's Road Central. Then proceed up Ladder Street (next to Lok Ku Road) to Hollywood Road to the Man Mo Temple. Open hours: 08:00 am – 06:00 pm Built in 1847, is one of the oldest and the most famous temples in Hong Kong and this remains the largest Man Mo temple in Hong Kong. It is a favorite with parents who come to pray for good progress for their kids in their studies. -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

1193Rd Minutes

Minutes of 1193rd Meeting of the Town Planning Board held on 17.1.2019 Present Permanent Secretary for Development Chairperson (Planning and Lands) Ms Bernadette H.H. Linn Professor S.C. Wong Vice-chairperson Mr Lincoln L.H. Huang Mr Sunny L.K. Ho Dr F.C. Chan Mr David Y.T. Lui Dr Frankie W.C. Yeung Mr Peter K.T. Yuen Mr Philip S.L. Kan Dr Lawrence W.C. Poon Mr Wilson Y.W. Fung Dr C.H. Hau Mr Alex T.H. Lai Professor T.S. Liu Ms Sandy H.Y. Wong Mr Franklin Yu - 2 - Mr Daniel K.S. Lau Ms Lilian S.K. Law Mr K.W. Leung Professor John C.Y. Ng Chief Traffic Engineer (Hong Kong) Transport Department Mr Eddie S.K. Leung Chief Engineer (Works) Home Affairs Department Mr Martin W.C. Kwan Deputy Director of Environmental Protection (1) Environmental Protection Department Mr. Elvis W.K. Au Assistant Director (Regional 1) Lands Department Mr. Simon S.W. Wang Director of Planning Mr Raymond K.W. Lee Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Ms Jacinta K.C. Woo Absent with Apologies Mr H.W. Cheung Mr Ivan C.S. Fu Mr Stephen H.B. Yau Mr K.K. Cheung Mr Thomas O.S. Ho Dr Lawrence K.C. Li Mr Stephen L.H. Liu Miss Winnie W.M. Ng Mr Stanley T.S. Choi - 3 - Mr L.T. Kwok Dr Jeanne C.Y. Ng Professor Jonathan W.C. Wong Mr Ricky W.Y. Yu In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms Fiona S.Y. -

Surrounded by Slogans Perpetual Protest in Public Space During the Hong Kong 2019 Protests

12 Spaces of perpetual protest The breakdown of ‘normal’; continuously The Study reacting to and accommodating the protests Surrounded by slogans Perpetual protest in public space during the Hong Kong 2019 protests Milan Ismangil On the way to the metro, I walk past graffiti and posters asking me to be conscious and supportive of the protests. In the metro itself footage of protesters is shown on the many television screens.1 Public space in Hong Kong can no longer be neutral, it seems. The protests in Hong Kong are entering their fifth month at the time of writing. Originally demanding the withdrawal of a controversial extradition bill, they quickly transformed into a larger cry for accountability of those in power, with universal suffrage and an independent investigation into police brutality amongst the five main demands. The Lennon Walls 2 that have popped up all over Hong Kong and other places across the world are home to post-its, posters and various other visual media, put there by anyone wishing to Fig. 1 (above): express their support for the movement. In this The ‘Lennon Bridge’ in Tai Wo Hau. article I discuss the transformation of Hong Fig. 2 (left): Kong’s public areas into spaces of perpetual Remembering the movement near Wong protest. Tai Sin temple. Fig. 3 (below): Appeals to history and memory at the Chinese t is nearly impossible to walk anywhere the attacks on protesters by assailants with University of Hong Kong. in Hong Kong today without encountering knives on 21 July 2019, and the second to Fig. -

Downloaded License

international journal of taiwan studies 3 (2020) 343-361 brill.com/ijts Review Essay ∵ Review of the Exhibition Oppression and Overcoming: Social Movements in Post-War Taiwan, National Museum of Taiwan History, 28 May 2019–17 May 2020 Susan Shih Chang Department of Communications and New Media, National University of Singapore, Singapore [email protected] Jeremy Huai-Che Chiang Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract This review article looks at “Oppression and Overcoming: Social Movements in Post- War Taiwan” (2019.5.28–2020.5.17), an exhibition at the National Museum of Taiwan History (nthm) through approaches of museum studies and social movement studies, and aims to understand its implication for doing Taiwan Studies. This review con- cludes that “Oppression and Overcoming” is significant as a novel museological prac- tice by being part of a continuation of social movements, which transformed the mu- seum to a space for civil participation and dialogue. This allows the exhibition to become a window for both citizens and foreigners to understand and realize Taiwan’s vibrant democracy and civil society. In addition, this review suggests that future © SUSAN SHIH CHANG AND JEREMY HUAI-CHE CHIANG, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24688800-00302009 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/24/2021 07:47:53AM via free access <UN> 344 Chang and Chiang exhibitions on social movements could demonstrate the possibility to position Taiwan in a global context to better connect with other countries in the Asian region. -

Branch Network & Corporate

BRANCH NETWORK & CORPORATE BANKING CENTRES Bank of China (Hong Kong) – Branch Network Hong Kong Island Branch Address Telephone Branch Address Telephone Central & Western District Quarry Bay Branch Parkvale, 1060 King’s Road, Quarry Bay, 2564 0333 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 Hong Kong Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 Queen’s Road West 2-12 Queen’s Road West, Sheung Wan, 2815 6888 Southern District (Sheung Wan) Branch Hong Kong Tin Wan Branch 2-12 Ka Wo Street, Tin Wan, Hong Kong 2553 0135 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 Stanley Branch Shop 401, Shopping Centre, Stanley Plaza, 2813 2290 Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 Hong Kong Central District 71 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2843 6111 Aberdeen Branch 25 Wu Pak Street, Aberdeen, Hong Kong 2553 4165 (Wing On House) Branch South Horizons Branch G38, West Centre Marina Square, 2580 0345 South Horizons, Ap Lei Chau, Hong Kong Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen’s Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, 2819 7277 Hong Kong South Horizons Branch Safe Box Shop 118, Marina Square East Centre, 2555 7477 Service Centre Ap Lei Chau, Hong Kong Western District Branch 386-388 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2549 9828 Wah Kwai Estate Branch Shop 17, Shopping Centre, Wah Kwai Estate, 2550 2298 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 2291 6081 Hong Kong 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong Chi Fu Landmark Branch Shop 510, Chi Fu Landmark, Pok Fu Lam, -

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong https://www.e-ir.info/2019/03/29/rival-securitising-attempts-in-the-democratisation-of-hong-kong/ NEVILLE CHI HANG LI, MAR 29 2019 This is an excerpt from New Perspectives on China’s Relations with the World: National, Transnational and International. Get your free copy here. The principle of “one country, two systems” is in grave political danger. According to the Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong signed in 1984, and as later specified in Article 5 of the Basic Law, i.e. the mini-constitution of Hong Kong, the capitalist system and way of life in Hong Kong should remain unchanged for 50 years. This promise not only settled the doubts of the Hong Kong people in the 1980s, but also resolved the confidence crisis of the international community due to the differences in the political and economic systems between Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As stated in the record of a meeting between Thatcher and Deng in 1982, the Prime Minister regarded the question of Hong Kong as an ‘immediate issue’ as ‘money and skill would immediately begin to leave’ if such political differences were not addressed (Margaret Thatcher Foundation 1982). -

In Hong Kong Restrictions on Rights to Peaceful Assembly and Freedom of Expression and Association

BEIJING’S “RED LINE” IN HONG KONG RESTRICTIONS ON RIGHTS TO PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND ASSOCIATION Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2019 Cover photo: An estimated 1.03 million people in Hong Kong took to the streets to protest the Extradition Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Bill on 9 June 2019. (Photo credit: Amnesty International) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2019 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 17/0944/2019 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1. BEIJING’S “RED LINE” IN HONG KONG 8 1.1 THE SINO-BRITISH JOINT DECLARATION AND THE BASIC LAW 8 1.2 NATIONAL SECURITY LEGISLATION 9 1.3 THE WHITE PAPER ON “ONE COUNTRY, TWO SYSTEMS” 10 2. -

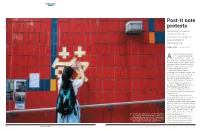

Post-It Note Protests Photos by Laurel Chor Photos by Laurel Hong Kong’S Lennon Walls Offer Bright Messages of Resistance Against Beijing’S Tightening Grip

LIFE & ARTS Post-it note protests Photos by Laurel Chor Photos by Laurel Hong Kong’s Lennon Walls offer bright messages of resistance against Beijing’s tightening grip LAUREL CHOR Contributing writer ll over Hong Kong, a colorful form of peaceful protest has A been blossoming. People have been writing their thoughts, demands and encouragement onto Post-it notes, and sticking them onto walls in public spaces, creating an eye-catching and instantly recognizable mosaic. They’ve bloomed on walls of footbridges and pedestrian tunnels, and on the sides of government buildings and highway pillars, with some torn down as quickly as they flowered, and others having lasted since early June. These temporary installations are called Lennon Walls, taking their name from the graffiti-covered, peace- themed wall in Prague first painted with a picture of the late musician John Lennon in 1980. The first Hong Kong Lennon Wall appeared on the sides of the legislature in 2014, during the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement, when major streets were occupied in the heart of the city for 79 days. Five years later, they have again become a powerful symbol in the former British colony, which has been rocked by almost two months of increasingly Ms. Ho (first name withheld), 14, said she was putting violent demonstrations. up a made-up character representing “dirty cops” The protests were sparked by a on the outskirts of the wall in Tai Po. “I want people proposed bill that would allow anyone to know that the cops are like this, that they don’t care about people, and don’t help people, and hit us.” in Hong Kong to be extradited back to mainland China, while the police 54 Nikkei Asian Review Aug.