British Rale in the Western Himalayan Hill State of Kangra, Which Began in 1846, Represented Both Continuities With, and Disjunc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kangra District Human Development Report

District Human Development Report Kangra Department of Planning Department Agricultural Economics Himachal Pradesh CSK Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University The Team CSK Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University Dr. S.C. Sharma Principal Investigator Virender Kumar Co-Investigators R. K. Sharma H.R. Sharma Planning DepartmenDepartment,t, Himachal Pradesh Basu Sood, Deputy Director Ravinder Kumar DPO, Kangra Sanjeev Sood, ARO Contents Message Foreword List of Tables, Boxes and Figures i-iii Chapter 1: Human Development Report- A Prologue 1-4 1.1: Human Development-Definition and Concept 2 1.2: Measuring Human Development 3 1.3: District Human Development Report of Kangra 3 Chapter 2: Kangra District- An Introduction 5-13 2.1: A Glimpse into the History of Kangra 6-9 2.2: Administrative Set Up 9-10 2.3: Demographic Profile 11-13 Chapter 3: Physiography, Natural Resources and Land Use 14-31 3.1: Topography 14 3.2: Climate 15 3.3: Forest Resources 15-16 3.3.1: Forest area by legal status 16-17 3.4: Water Resources and Drainage 17 3.4.1: Kuhl Irrigation 17-19 3.4.2: Lakes and Reservoirs 19-20 3.4.3: Ground Water 20 3.5: Soils 21-22 3.6: Mineral Resources 22-24 3.6.1: Slates 23 3.6.2: Limestone 23 3.6.3: Oil and Natural Gas 23 3.6.4: Sand, stone and bajri 24 3.6.5: Iron and coal 24 3.7: Livestock Resources 24-25 3.8: Land Utilization Pattern 25-28 3.8.1: Agriculture-Main Livelihood Option 28-29 Chapter 4: Economy and Infrastructure 32-40 4.1: The Economy 32-34 4.2: Infrastructure 35 4.2.1: Road Density 35-36 4.2.2: Transportation Facility -

State Wise Teacher Education Institutions (Teis) and Courses(As on 31.03.2019) S.No

State wise Teacher Education Institutions (TEIs) and Courses(As on 31.03.2019) S.No. Name and Address of the Institution State Management Courses and Intake 1 A - One College ,Vill. -Raja ka Bagh,Post -Nagabari,Tehsil -Nupur Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100 Abhilashi College of Education, Dept. of Physical Education, Near Chowk, 2 Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 200, B.P.Ed. 50 Tehsil - Sardar, Dist.-Mandi (HP) 3 Abhilasi j.B.T. Training Institute ,Tehsil -Sadar,Distt. -Mandi Himachal Pradesh Private D.El.Ed. 50 Adarsh Public Educational College, ,Dehar-Tehsil-Sunder Nagar, Distt-Mandi, 4 Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100 HP Akal College of Education, ,Plot No. 45, Baru Sahib, paccad, Simour, Himachal 5 Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100 Pradesh 6 Astha College of Education ,Po -Kunihar,Block Kunihar Tehsil -Arki Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100 Awasthi Memorial School of Teachers Education ,Vill.-Dharamshala,sham 7 Himachal Pradesh Private D.El.Ed. 50 Nagar Awasti Collage of Education ,Village - Shtam Nagar,Post - Dari, Tehsil - 8 Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100 Dharamshala Baba Kirpal Dass College of Education for Women, Paonta Sahib, Sirmour, 9 Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100, D.El.Ed. 50 Himachal Pradesh , Baba Kirpal Dass Degree College for Women, Ponta Sahib, Sirmor- 173025, 10 Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 50 Himachal Pradesh 11 Bhardwaj Shikshan Sansthan ,Vill.-Baral,Karsog Himachal Pradesh Private - Blooms College of Education, Above State Bank of Patiala, Bhojpur, 12 Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. 100, D.El.Ed. 50 Sundernagar, District- Mandi, Himachal Pradesh, Pin Code- 174401 13 Bushhr B.Ed Institute ,Post- Nogli,Rampur Himachal Pradesh Private B.Ed. -

Khalistan: a History of the Sikhs' Struggle from Communal Award To

Khalistan: A History of the Sikhs’ Struggle from Communal Award to Partition of India 1947 This Dissertation is Being Submitted To The University Of The Punjab In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy In History Ph. D Thesis Submitted By Samina Iqbal Roll No. 1 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Muhammad Iqbal Chawla Department of History and Pakistan Studies University of the Punjab, March, 2020 Khalistan: A History of the Sikhs’ Struggle from Communal Award to Partition of India 1947 Declaration I, hereby, declare that this Ph. D thesis titled “Khalistan: A History of the Sikhs’ Struggle from Communal Award to Partition of India 1947” is the result of my personal research and is not being submitted concurrently to any other University for any degree or whatsoever. Samina Iqbal Ph. D. Scholar Dedication To my husband, my mother, beloved kids and all the people in my life who touch my heart and encouraged me. Certificate by Supervisor Certificate by Research Supervisor This is to certify that Samina Iqbal has completed her Dissertation entitled “Khalistan: A History of the Sikhs’ Struggle from Communal Award to Partition of India 1947” under my supervision. It fulfills the requirements necessary for submission of the dissertation for the Doctor of Philosophy in History. Supervisor Chairman, Department of History & Pakistan Studies, University of the Punjab, Lahore Submitted Through Prof. Dr. Muhammad Iqbal Chawla Prof. Dr. Muhammad Iqbal Chawla Dean, Faculty of Arts & Humanities, University of the Punjab, Lahore. Acknowledgement Allah is most merciful and forgiving. I can never thank Allah enough for the countless bounties. -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

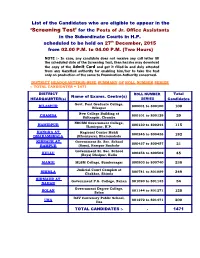

Roll Number Series :: Total Candidates = 1471

List of the Candidates who are eligible to appear in the ‘Screening Test’ for the Posts of Jr. Office Assistants in the Subordinate Courts in H.P. scheduled to be held on 27th December, 2015 from 02.00 P.M. to 04.00 P.M. (Two Hours) NOTE :- In case, any candidate does not receive any call letter till the scheduled date of the Screening Test, then he/she may download the copy of the Admit Card and get it filled-in and duly attested from any Gazetted authority for enabling him/her to take the test only on production of the same to Examination Authority concerned. DISTRICT HEADQUARTER(S)-WISE SUMMARY OF ROLL NUMBER SERIES :: TOTAL CANDIDATES = 1471 DISTRICT ROLL NUMBER Total Name of Exams. Centre(s) HEADQAURTER(s) SERIES Candidates Govt. Post Graduate College, BILASPUR 800001 to 800100 100 Bilaspur New College Building at CHAMBA 800101 to 800129 29 Sultanpur, Chamba NSCBM Government College, HAMIRPUR 800130 to 800244 115 Hamirpur, H.P. KANGRA AT Regional Centre Mohli 800245 to 800436 192 DHARAMSHALA (Khaniyara), Dharamshala KINNAUR AT Government Sr. Sec. School 800437 to 800457 21 RAMPUR (Boys), Rampur Bushahr Government Sr. Sec. School KULLU 800458 to 800502 45 (Boys) Dhalpur, Kullu MANDI MLSM College, Sundernagar 800503 to 800740 238 Judicial Court Complex at SHIMLA 800741 to 801089 349 Chakkar, Shimla SIRMAUR AT Government P.G. College, Nahan 801090 to 801143 54 NAHAN Government Degree College, SOLAN 801144 to 801271 128 Solan DAV Centenary Public School, UNA 801272 to 801471 200 Una TOTAL CANDIDATES :- - 1471 :: DISTRICT HEADQUARTER, BILASPUR :: Total Roll Number Series Particulars of Examination Centre(s) Candidates Govt. -

Cijhar 23.Pmd

1 1 Archaeology on Coorg with Special Reference to Megaliths *Dr. N.C. Sujatha Abstract Coorg, located in the southern parts of modern Karnataka is a land locked country, situated between the coastal plains and the river plains of Karnataka. This hilly region part of Western Ghats is covered with thick Kodagu as it colloquially called is the birth place of river Kaveri and other rivers. The mountains of this region are part of the Sahyadri ranges. The high raised mountain ranges like Pushpagiri, Tadiyandamol, and Brahmagiri are the rich reserves for rare animals and flora and fauna. These high rising mountains and peaks causes heavy to very heavy rainfall during the s-w monsoon. This hilly region is known as ‘Kodugunadu’ , ‘ kudunad’, ‘Maleppa’ etc. Key Words: Kodagu, Kudunadu, Mythology, proto-history, Megaliths, Kaveri, Dolemens, strucuture, inhabitated, tribes, poleyas, Eravas, Irulas, Gowdas, Pandava-pare, Introduction - The study of the history of Kodagu begins with discovery of hundreds of dolmen, megaliths burials, pottery and other artifacts found in those places which might have been inhabited by people of pre-historical period. Kodagu is inhabited by the Kodavas who call themselves as ‘Kaverammada Makka’; children of river Kaveri whom they adore and consider worthy of worship. It is part of their life and culture. The other people who inhabit here are the Gowdas, the Malayali speaking, Kannada speaking tribes, some aboriginals like Poleyas, Eravas, Jenu kurubas, Betta Kurubas, Irulas, Gonds, Iris, Kavadis and Thodas etc. For centuries the history of Kodagu was non-existent, as nothing was known about Coorg, except its distinct socio-cultural background added with rich cultural heritage. -

Page 1 of 327 30 Clerk 692 1458959 Aarushi Rana D/O: Arun Singh Village Samkar Post Office Dhameta Teh Fatehpur Dhameta Khas Rana (200) Kangra

Rejection list of the candidates for the Post of Clerk, Post Code-692, for the reason fee not received. Sr. No. Post Post App. Id Name of Father/Husband Permanent Address Name Code Candidate Name 1 Clerk 692 1481057 VILL. MELTH, P.O. RAWLAKIAR, TEH. KOTKHAI DISTT SHIMLA HP 2 Clerk 692 1468646 VILLAGE KAMLADINGRI POST OFFICE BASANTPUR 3 Clerk 692 1453158 Aaditya Kaushal S/O Manoj Kumar Village and post office Diyargi Tehsil Balh Distt Mandi (H.P) 4 Clerk 692 1752176 Aaditya Vashishth S/O Brijmohan HOUSE NO.1 WARD NO. 1 NIHAL SECTOR BILASPUR Bilaspur (209) Sharma Bilaspur 5 Clerk 692 1411360 Aakanksha D/O: Kul Bhushan tehsil palampur Khaira Uparla (545) Kangra Awasthi 6 Clerk 692 1644119 Aakanksha Thakur D/O: R C Thakur Thakurs Villa Dudhli Up Muhal Dudhali Shimla 7 Clerk 692 1515311 Aakash sunil mehta 1/3, new railway road, near bindal hospital, adarsh nagar 8 Clerk 692 1230289 Aakash S/O Hans Raj Village Tillu,Post Office Bela, Tillu Kash 9 Clerk 692 1664611 Aakash Sharma Manohar Lal VPO Padhar 10 Clerk 692 1405208 aanchal kapil Vipen kapil Negi cloth house chaupal 11 Clerk 692 1270282 Aanchal Devi D/O: Raj Kumar NULL NULL NULL Tehsil Nahan Nagal Saketi (141) Sirmaur 12 Clerk 692 1838336 Aanchal Mahant D/O: Mohinder vill. malipather p.o. raison Mahant 13 Clerk 692 1734665 Aanchal Verma D/O Deepak Verma Verma Cottage Bothwell Estate Near Govt College Sanjauli Post Office Sanjauli Teh Shimla Shimla Urban(T) Shimla 14 Clerk 692 1755563 Aarohi Nee Fulan Laxmi Nand Vill Kot Dhalyas, PO Kot Khamradha DEVI 15 Clerk 692 1561272 Aarti Subhash -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : HIMACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT : Bilaspur Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 GOVT LIVESTOCK FARM KOTHIPURA P. O. KOTHIPURA TEH SADAR DITT. BILASPUR MIMACHAL PRADESH PIN CODE: 174001, STD 1972 10 - 50 CODE: 01978, TEL NO: 280034, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 2 TARA CHAND VILLAGE GARA PO SWAHAN TEH SH NAINA DEVI DISTT. BILAS PUR HP PIN CODE: 174310, 1990 10 - 50 STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 1410-Quarrying of stone, sand and clay 3 GAMMUNINDIALIMITED GAMMONHOUSEVSMARGPRABHADEVIDADARMUMBAI NTPCKOLDAMBARMANADISTT. 1954 10 - 50 BILASPURHP PIN CODE: 400025, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 2102-Manufacture of corrugated paper and paperboard and of containers of paper and paperboard 4 RAJVANSHI CORRUGATING PACKAGING GOALTHAI PO GOALTHRI DISTT BILASPOR HP , PIN CODE: 174201, STD CODE: 98160, TEL 2005 10 - 50 INDUSTRY NO: 48623, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 2411-Manufacture of basic chemicals except fertilizers and nitrogen compounds 5 ROSIN AND TARPIN FACTORY VILL RAGUNATHPURA P.O .RAGUNATHPURA TEH SADAR DISTT. BILASPUR HP PIN CODE: 1969 101 - 500 174005, STD CODE: 01978, TEL NO: 222464, FAX NO: 222464, E-MAIL : N.A. -

April, 1987 Edited "By Mahesh G, -Ragmi

Regmi Research (Private) Ltd. ISSN: 0034-348X Regmi Research Series Year 19, No. 4 Kathm'Bndu: April, 1987 Edited "by Mahesh G, -Ragmi_ Contents -� 1 • Garhwal llJ)pointments, :A.D. 1805- • •• 4E( 2. Gorkha After Tha Licchavi J?eriod ••• 48 • , r .. ,. -···' '- 3.: - F.J:om the: Ya.muns to the Sutl,Ji ;-.. - • • • ��o( ' �. ; if ·, .o:·J Jajarkot •• •,.f , 4. :: j(. 5. .An Error in -Colonel Jc..irkpatrick •-� Account of Nepal • •• .5.5 6. -· Night J?atrols in I�at_hmandu ••• 56 ' ' 1 7 •. : Land J.$signm.e�11$ 1to _ Sabuj rocokllpa.;iy - .. ""' -· u: .:, .• � "'51 i • • ••• ,. ; • .. ,..... _ , � • ; • -� -:-• n • . � l rr1 L. �-. l , ·r. j . -� �'.: '; i.e. .:, Traffic l'i1'n ••,, n.:c:• ' 9:1s...-e '.) r Gl!i"rhwal. .,' ;.: i 9. Ap_pc>intments ir the Jaalu.J?a-;Sut_lej' �egiqit'' •• ·; ' . :,.;,, i,•8rl . ..... �-- -� .. ":,' '>." . ' ' '; ;" . • : . 5 J ' � �-. 6'd' · 1_0. -.t-Troop Movement·e,j.. : .A..D. ·1805 u .. � •: '•,J ************ ' ,I.:•. } · Ragint fPr:f�teif Jte�ear_dh -- ! ,,-, ---.•.(,.,i7 ,.., ,,•..... l:.2 ,, • :ttct';,: • J;' � � • i • 0 ' 'i'+ Latimpat, Kathmandu, Nepal � 4-11927 T�lephone: ., �-� - 'l <.. ; J.. , .:.. ...... (For private study and researah·pnly; not meant tor public sale, distribution and ' ►· ,- -1. ' di�play)..: "i •.L �.. � �- :).,;, . ' /) :· ; 46 G:-::rhwcl Appointrc1;:_mts I A, D, 1805 1. Appointment of Khatri Brothers as Subbas I Dhttuk.al 1.hatri, Surabir I .. hatri, and Ranabir 1.hatri belonged to Kaski district. They were sons of Shiva Khatri and u grandsons of Chasmu Khatri. On Thursday, Ashaah Badi 1, 1862 (Jne 1805) they were appointed Sub bas of one-third of the lv1a6hesh, hill, and Bhot territories of Garh. ·:'hey replacec Ranadhir 13:asnet. -

Nepali Times Deserves Thanks for to the Nepali People, Among Whom It at Par with Bihar So That We Never Forge in the Know’

#278 23 - 29 December 2005 16 pages Rs 30 Prachanda’s new path ith less than two weeks to go before their ceasefire extension expires on 3 January, the Maoists say they are now training their p8-9 W sights on the capital. In briefings to select journalists taken to their heartland in Rukum MOUNTAINS+ earlier this month, senior rebel commanders hinted they were following a BIKES=THRILLS two-track policy of using the political process and, if that path is blocked, step up guerrilla attacks in and around the capital to pressure the regime. The Maoists have been holding large meetings Weekly Internet Poll # 278 this month throughout the midwest from where they launched the war 10 years ago. The aim is to explain Editorial p2 Q... Is it right for the main political parties to boycott municipal and general elections? the decisions taken at their central committee meeting Hapless new year and also the deal struck with the seven-party alliance. Total votes:5,012 Their battle cry is: "To Kathmandu." One of the videos shown at the rallies depicts Pushpa Kamal Dahal (Prachanda) wiping tears as he watched an opera about fallen ‘martyrs’ titled Yuddha Maidan Bata Pharkada (Returning from the Battlefield). This grab (left) from the video is the most recent picture of Dahal and shows a dapper comrade with graying hair and moustache. The video was taken Weekly Internet Poll # 279. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com after the central committee in Chungbang on the Rolpa-Rukum border in Q... What do you think 2006 has in store October. -

Kingship and Polity on the Himalayan Borderland Himalayan the on Polity and Kingship

8 ASIAN BORDERLANDS Moran Kingship and Polity on the Himalayan Borderland Arik Moran Kingship and Polity on the Himalayan Borderland Rajput Identity during the Early Colonial Encounter Kingship and Polity on the Himalayan Borderland Asian Borderlands Asian Borderlands presents the latest research on borderlands in Asia as well as on the borderlands of Asia – the regions linking Asia with Africa, Europe and Oceania. Its approach is broad: it covers the entire range of the social sciences and humanities. The series explores the social, cultural, geographic, economic and historical dimensions of border-making by states, local communities and flows of goods, people and ideas. It considers territorial borderlands at various scales (national as well as supra- and sub-national) and in various forms (land borders, maritime borders), but also presents research on social borderlands resulting from border-making that may not be territorially fixed, for example linguistic or diasporic communities. Series Editors Tina Harris, University of Amsterdam Willem van Schendel, University of Amsterdam Editorial Board Members Franck Billé, University of California, Berkeley Duncan McDuie-Ra, University of New South Wales Eric Tagliacozzo, Cornell University Yuk Wah Chan, City University Hong Kong Kingship and Polity on the Himalayan Borderland Rajput Identity during the Early Colonial Encounter Arik Moran Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Sketch of raja Sansar Chand Katoch II, Kangra c. 1800 Courtesy: The Director, Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 560 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 675 7 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462985605 nur 740 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The author / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. -

Screening Test for the Posts of Jr

Roll Number Series-wise & Examination Centre-wise List of the Candidates who are eligible to appear in Screening Test for the Posts of Jr. Office Assistant in the High Court of H.P. scheduled to be held on 13th December, 2015 between 10.00 A.M. to 12.00 Noon (2 hours) NOTE :- In case, any candidate does not receive any call letter till the scheduled date of the Screening Test, then he/she may download the copy of the Admit Card and get it filled-in and duly attested from any Gazetted authority for enabling him/her to take the test only on production of the same to Examination Authority concerned. :: At High Court of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla :: Total Strength : 343 Candidates Roll Number Series : 600001 to 600343 :: At Bells Institute of Management & Technology :: Knowledge City, Mehli, Shimla – 171 013 Total Strength : 1400 Candidates Roll Number Series : 600344 to 601743 Sl. Roll Name of The Father's/Husband's Name & No. No. Candidate Correspondence Address Bhupinder Singh Thakur,Thakur Lodge Nr Chitkara 1 600001 Gunjan Thakur Park,Lower Kaithu Shimla,HP Shimla-171003 Sh Mast Ram Verma,C/O Sh B S Verma ,VPO 2 600002 Ishwar Verma RAJHANA TEHSIL SHIMLA,HIMACHAL AND SHIMLA-171009 Amar Paul Baldev Singh,Vpo-Dadhol Teh.-Ghumarwin,DISTT.- 3 600003 Singh BILASPUR,HIMACHAL PRADESH-174023 Lt. Chain Singh,Vill-Kasauli,P.O.-Garkhal,Himachal 4 600004 Kuldeep Kumar & Solan-173201 Mandeep Munshi Ram,O/O Bdo Sarkaghat,Tehsil 5 600005 Kumar Sarkaghat,Mandi HP-175024 Sunder Singh,Vill-Dhar,P.O.-Churdh,Himachal 6 600006 Ritesh Kumar Pradesh & Mandi-175018 Rohit Kumar Rakesh Kumar Verma,Vill.