Downloaded from Brill.Com10/03/2021 08:12:34PM Via Free Access | Maya H.T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pramoedya's Developing Literary Concepts- by Martina Heinschke

Between G elanggang and Lekra: Pramoedya's Developing Literary Concepts- by Martina Heinschke Introduction During the first decade of the New Order, the idea of the autonomy of art was the unchallenged basis for all art production considered legitimate. The term encompasses two significant assumptions. First, it includes the idea that art and/or its individual categories are recognized within society as independent sub-systems that make their own rules, i.e. that art is not subject to influences exerted by other social sub-systems (politics and religion, for example). Secondly, it entails a complex of aesthetic notions that basically tend to exclude all non-artistic considerations from the aesthetic field and to define art as an activity detached from everyday life. An aesthetics of autonomy can create problems for its adherents, as a review of recent occidental art and literary history makes clear. Artists have attempted to overcome these problems by reasserting social ideals (e.g. as in naturalism) or through revolt, as in the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century which challenged the aesthetic norms of the autonomous work of art in order to relocate aesthetic experience at a pivotal point in relation to individual and social life.* 1 * This article is based on parts of my doctoral thesis, Angkatan 45. Literaturkonzeptionen im gesellschafipolitischen Kontext (Berlin: Reimer, 1993). I thank the editors of Indonesia, especially Benedict Anderson, for helpful comments and suggestions. 1 In German studies of literature, the institutionalization of art as an autonomous field and its aesthetic consequences is discussed mainly by Christa Burger and Peter Burger. -

Ambiguitas Hak Kebebasan Beragama Di Indonesia Dan Posisinya Pasca Putusan Mahkamah Konstitusi

Ambiguitas Hak Kebebasan Beragama di Indonesia dan Posisinya Pasca Putusan Mahkamah Konstitusi M. Syafi’ie Pusat Studi HAM UII Jeruk Legi RT 13, RW 35, Gang Bakung No 157A, Bangutapan, Bantul Email: syafi[email protected] Naskah diterima: 9/9/2011 revisi: 12/9/2011 disetujui: 14/9/2011 Abstrak Hak beragama merupakan salah satu hak yang dijamin dalam UUD 1945 dan beberapa regulasi tentang hak asasi manusia di Indonesia. Pada pasal 28I ayat 1 dinyatakan bahwa hak beragama dinyataNan seEagai haN yang tidaN dapat diNurang dalam keadaan apapun, sama halnya dengan hak hidup, hak untuk tidak disiNsa, haN NemerdeNaan piNiran dan hati nurani, haN untuk tidak diperbudak, hak untuk diakui sebagai pribadi di hadapan huNum, dan haN untuN tidaN dituntut atas dasar huNum yang berlaku surut. Sebagai salah satu hak yang tidak dapat dikurangi, maNa haN Eeragama semestinya EerlaNu secara universal dan non disNriminasi.TerEelahnya Maminan terhadap haN NeEeEasan beragama di tengah maraknya kekerasan yang atas nama agama mendorong beberapa /60 dan tokoh demokrasi untuk melakukan judicial review terhadap UU No. 1/PNPS/1965 tentang Pencegahan 3enyalahgunaan dan atau 3enodaan Agama. 8ndang-8ndang terseEut dianggap Eertentangan dengan Maminan haN Eeragama yang tidak bisa dikurangi dalam keadaan apapun. Dalam konteks tersebut, Mahkamah Konstitusi menolak seluruhnya permohonan judicial review 88 terseEut, walaupun terdapat disenting opinion dari salah satu hakim konstitusi. Pasca putusan Mahkamah Konsitusi, Jurnal Konstitusi, Volume 8, Nomor 5, Oktober 2011 ISSN 1829-7706 identitas hak beragama di Indonesia menjadi lebih terang, yaitu bisa dikurangi dan dibatasi. Putusan Mahkamah Konstitusi tidak menjadi kabar gembira bagi para pemohon, karena UU. No. 1/ PNPS/1965 bagi mereka adalah salah alat kelompok tertentu untuk membenarkan kekerasan atas nama agama kontemporer. -

INDO 7 0 1107139648 67 76.Pdf (387.5Kb)

THE THORNY ROSE: THE AVOIDANCE OF PASSION IN MODERN INDONESIAN LITERATURE1 Harry Aveling One of the important shortcomings of modern Indonesian literature is the failure of its authors, on the whole young, well-educated men of the upper and more modernized strata of society, to deal in a convincing manner with the topic of adult heterosexual passion. This problem includes, and partly arises from, an inadequacy in portraying realistic female char acters which verges, at times, on something which might be considered sadism. What is involved here is not merely an inability to come to terms with Western concepts of romantic love, as explicated, for example, by the late C. S. Lewis in his book The Allegory of Love. The failure to depict adult heterosexual passion on the part of modern Indonesian authors also stands in strange contrast to the frankness and gusto with which the writers of the various branches of traditional Indonesian and Malay litera ture dealt with this topic. Indeed it stands in almost as great a contrast with the practice of Peninsular Malay literature today. In Javanese literature, as Pigeaud notes in his history, The Literature of Java, "Poems and tales describing erotic situations are very much in evidence . descriptions of this kind are to be found in almost every important mythic, epic, historical and romantic Javanese text."^ In Sundanese literature, there is not only the open violence of Sang Kuriang's incestuous desires towards his mother (who conceived him through inter course with a dog), and a further wide range of openly sexual, indeed often heavily Oedipal stories, but also the crude direct ness of the trickster Si-Kabajan tales, which so embarrassed one commentator, Dr. -

Epistemologi Intuitif Dalam Resepsi Estetis H.B. Jassin Terhadap Al-Qur'an

Epistemologi Intuitif dalam Resepsi Estetis H.B. Jassin terhadap Al-Qur’an Fadhli Lukman1 Abstract This article discusses two projects of well-known literary critic H.B. Jassin on the Qur’an. Jassin’s great career in literary criticism brought him to the domain of al-Qur’an, with his translation of the Qur’an Al-Qur’anul Karim Bacaan Mulia and his rearrangement of the writing of the Qur’an into poetic makeup. Using descriptive and analytical methods, this article concludes that the two works of H.B. Jassin came out of his aesthetic reception of the Qur’an. Epistemologically, these two kinds of reception are the result of Jassin intuitive senses, which he nourished for a long period. Abstrak Artikel ini membincang dua proyek sastrawan kenamaan Indonesia, H.B. Jassin, seputar Al-Qur’an. Karir besar Jassin dalam sastra mengantarkannya kepada ranah al-Qur’an, dengan karya terjemahan berjudul Al-Qur’anul Karim Bacaan Mulia dan penulisan mushaf berwajah puisi. Dengan menggunakan metode deskriptif-analitis, artikel ini berakhir pada kesimpulan bahwa kedua karya H.B Jassin merupakan resepsi estetisnya terhadap Al-Qur’an. Berkaitan dengan epistemologi, kedua bentuk resepsi ini merupakan hasil dari pengetahuan intuitif Jassin yang ia asah dalam waktu yang panjang. Keywords: resepsi estetis, epistemologi intuitif, sastra, shi‘r 1Mahasiswa Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta/Alumnus Pondok Pesantren Sumatera Thawalib Parabek. E-mail: [email protected] Journal of Qur’a>n and H}adi@th Studies – Vol. 4, No. 1, (2015): 37-55 Fadhli Lukman Pendahuluan Sebagai sebuah kitab suci, al-Qur’an mendapatkan resepsi yang luar biasa besar dari penganutnya. -

88 DAFTAR PUSTAKA A. Buku Abdul Muis, Metode Penulisan Skripsi Dan

88 DAFTAR PUSTAKA A. Buku Abdul Muis, Metode Penulisan Skripsi dan Metode Penelitian Hukum, Fakultas Hukum, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, 1990 Al Ahmady Abu An Nur, Saya Ingin Bertobat Dari Narkoba, Darul Falah, Jakarta, 2000 Andi Hamzah, Perlindungan Hak-Hak Asasi Manusia Dalam Kitab Undang- Undang Hukum Acara Narkoba, Jakarta, 2004 Anggota IKAPI, Undang-Undang Psikotropika dan Zat Adiktif Lainnya, Fokusmedia, Juni 2010 Badan Narkotika Nasional Republik Indonesia, Komunikasi Penyuluyhan Pencegahan Penyalahgunaan Narkoba, Jakarta, 2004 Barda Nawawi Arief, Beberapa Aspek Kebijaksanaan Penegakan dan Pengembangan Hukum Pidana, Citra Aditya Bakti, Bandung, 1998 Chaeruddin dan Syarif Fadillah, Korban Kejahatan dalam Perpsektif Victimologi dan Hukum Pidana Islam, Ghalia Press, Cetakan Pertama, Jakarta, 2004 Dadang Hawari, Penyalahgunaan dan Ketergantungan NAZA (Narkotika, Alkohol dan Zat Adiktif), Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, 2003 Didik M. Arief Mansur dan Elisatris Gultom, Urgensi Perlindungan Korban Kejahatan, Antara Norma dan Realita, Raja Grafindo Persada, Jakarta, 2007 EY Kanter dan SR Sianturi, Asas-asas Hukum Pidana di Indonesia, Storia Grafika, Jakarta, 2002 Farouk Muhammad, Pengubahan Perilaku dan Kebudayaan Dalam Rangka Peningkatan Kualitas Pelayanan Polri, Jurnal Polisi Indonesia, Tahun 2, April 2000 – September 2000 H. M. Kamaluddin, Hukum Pembuktian Pidana dan Perdata Dalam Teori dan Praktek, Tanpa Penerbit, Medan, 1992 Hilaman Hadikusuma, Bahasa Hukum Indonesia, Alumni, Bandung, 1992 Kartini Kartono, -

I COHESION ANALYSIS of SOEKARNO's SPEECH ENTITLED

COHESION ANALYSIS OF SOEKARNO’S SPEECH ENTITLED ONLY A NATION WITH SELF RELIANCE CAN BECOME A GREAT NATION THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Degree of Bachelor of Education in English Education by Abdul Ghofar 113411044 EDUCATION AND TEACHER TRAINING FACULTY WALISONGO STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2018 i ii iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the name of Allah, the beneficent the most merciful All praise is only for Allah, the Lord of the world, the creator of everything in this universe, who has giving the blessing upon the researcher in finishing this research paper. Peace and blessing be upon to our beloved prophet Muhammad SAW, his families, companions, and all his followers. The researcher realized that cannot complete this final project without the help of others. Many people have helped me during writing this final project and it would be impossible to mention of all them. The writer wishes, however to give my sincerest gratitude and appreciation to: 1. Dr. H. Raharjo, M.Ed.St as the Dean of Education and Teacher Training Faculty. 2. Dr. H. Ikhrom, M.Ag as the Head of English Department and Sayyidatul Fadlillah, M.Pd as the Secretary of English Department. 3. Dra. Hj. Siti Mariam., M.Pd as the first advisor for patience in providing careful guidance, helpful correction, very good advice as well suggestion and encouragement during the consultation. 4. Daviq Rizal, M.Pd. as the second advisor, who has carefully and correctly read the final project for its improvement and has encouraged me to finish my final project. -

JSS 072 0A Front

7-ro .- JOURNAL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY JANUAR ts 1&2 "· THE SIAM SOCIETY PATRON His Majesty the King VICE-PATRONS Her Majesty the Queen Her Royal Highness the Princess Mother Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn HON . M E MBE R S The Ven. Buddhadasa Bhikkhu The Ven. Phra Rajavaramuni (Payu!to) Mr. Fua Haripitak Dr. Mary R. Haas Dr. Puey Ungphakorn Soedjatmoko Dr. Sood Saengvichien H.S.H. Prince Chand Chirayu Rajni Professor William J. Gedney HON. VIC E-PRESIDF.NTS Mr. Alexander B. Griswold Mom Kobkaew Abhakara Na Ayudhya H.S.H. Prince Subhadradis Diskul COU N CIL.. OF 'I'HE S IAM S O C IETY FOR 19841 8 5 President M.R. Patanachai Jayant Vice-President and Leader, Natural History Section Dr. Tern Smitinand Vice-President Mr. Dacre F.A. Raikes Vice-President Dr. Svasti Srisukh Honorary Treasurer Mrs. Katherine B. Buri Honorary Secretary Mrs. Nongyao Narumit Honorary Editor. Dr. Tej Bunnag Honorary Librarian Khi.m .Varun Yupha Snidvongs Assistant Honorary Treasurer Mr. James Stent Assistant Honorary Secretary Mrs. Virginia M. Di Crocco Assistant Honorary Librarian Mrs. Bonnie Davis Mr. Sulak Sivaraksa Mr. Wilhelm Mayer Mr. Henri Pagau-Clarac Dr. Pornchai Suchitta Dr. Piriya Krairiksh Miss A.B. Lambert Dr. Warren Y. Brockelman Mr. Rolf E. Von Bueren H.E. Mr. W.F.M. Schmidt Mr. Rich ard Engelhardt Mr. Hartmut Schneider Dr. Thawatchai Santisuk Dr. Rachit Buri JSS . JOURNAL ·"' .. ·..· OF THE SIAM SOCIETY 75 •• 2 nopeny of tbo ~ Society'• IJ1nQ BAN~Olt JANUARY & JULY 1.984 volume 72 par_ts 1. & 2 THE SIAM SOCIETY 1984 • Honorary Editor : Dr. -

Al-Qur'a>N Al-Kari>M Bacaan Mulia Karya H.B. Jassin)

KUTUB ARTISTIK DAN ESTETIK AL-QUR’A>N (Kajian Resepsi atas Terjemahan Surat al-Rah}ma>n dalam Al-Qur’a>n Al-Kari>m Bacaan Mulia Karya H.B. Jassin) Oleh: Muhammad Aswar NIM. 1420510081 TESIS Diajukan kepada Program Pascasarjana Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Magister dalam Ilmu Agama Islam Program Studi Agama dan Filsafat Konsentrasi Studi Qur’an Hadis YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii iii iv v vi MOTTO “Musik muncul dalam masyarakat bersamaan dengan munculnya peradaban; dan akan hilang dari tengah masyarakat ketika peradaban mundur.” ~ Ibn Khaldun ~ vii Untuk istriku, Hilya Rifqi dan Najma, anak-anakku tercinta Dari mana tanganmu belajar menggenggam? viii PEDOMAN TRANSLITERASI ARAB-LATIN Transliterasi adalah kata-kata Arab yang dipakai dalam penyusunan skripsi ini berpedoman pada surat Keputusan Bersama Menteri Agama dan Menteri Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Republik Indonesia, Nomor 158 Tahun 1987 dan Nomor 0543b/U/1987. I. Konsonan Tunggal Huruf Nama Huruf Latin Nama Arab Alif Tidak dilambangkan Tidak dilambangkan ا ba‘ b be ة ta' t te ت (s\a s\ es (dengan titik di atas ث Jim j je ج (h}a‘ h{ ha (dengan titik di bawah ح kha’ kh ka dan ha خ Dal d de د (z\al z\ zet (dengan titik di atas ذ ra‘ r er ر Zai z zet ز Sin s es ش Syin sy es dan ye ش (s}ad s} es (dengan titik di bawah ص (d{ad d{ de (dengan titik di bawah ض (t}a'> t} te (dengan titik di bawah ط (z}a' z} zet (dengan titik di bawah ظ (ain ‘ koma terbalik ( di atas‘ ع Gain g ge غ ix fa‘ f ef ف Qaf q qi ق Kaf k ka ك Lam l el ه Mim m em ً Nun n en ُ Wawu w we و ha’ h H هـ Hamzah ’ apostrof ء ya' y Ye ي II. -

ASIAN REPRESENTATIONS of AUSTRALIA Alison Elizabeth Broinowski 12 December 2001 a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

ABOUT FACE: ASIAN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUSTRALIA Alison Elizabeth Broinowski 12 December 2001 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University ii Statement This thesis is my own work. Preliminary research was undertaken collaboratively with a team of Asian Australians under my co-direction with Dr Russell Trood and Deborah McNamara. They were asked in 1995-96 to collect relevant material, in English and vernacular languages, from the public sphere in their countries of origin. Three monographs based on this work were published in 1998 by the Centre for the Study of Australia Asia Relations at Griffith University and these, together with one unpublished paper, are extensively cited in Part 2. The researchers were Kwak Ki-Sung, Anne T. Nguyen, Ouyang Yu, and Heidi Powson and Lou Miles. Further research was conducted from 2000 at the National Library with a team of Chinese and Japanese linguists from the Australian National University, under an ARC project, ‘Asian Accounts of Australia’, of which Shun Ikeda and I are Chief Investigators. Its preliminary findings are cited in Part 2. Alison Broinowski iii Abstract This thesis considers the ways in which Australia has been publicly represented in ten Asian societies in the twentieth century. It shows how these representations are at odds with Australian opinion leaders’ assertions about being a multicultural society, with their claims about engagement with Asia, and with their understanding of what is ‘typically’ Australian. It reviews the emergence and development of Asian regionalism in the twentieth century, and considers how Occidentalist strategies have come to be used to exclude and marginalise Australia. -

THE MANGO TREE ...Suvimalee

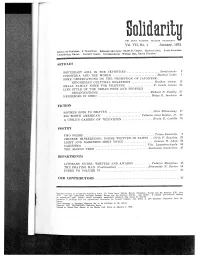

II oli i UBI BONI TACENT. MALUM Vol. VII, No.1 January, 1972 Editor and publisher: F. Sionil Jose. Editorial Advirsers: Onofre D. Corpuz, Mochtar Lubis, Sulak Sivaraksa. Contributing Editor: Leonard Casper. Correspondents:, Willam Hsu, Edwin Thumb"". -- ARTICLES SOUTHEAST ASIA IN THE SEVENTIES ...................... Soedjahno7co 3 INDONESIA AND THE WORLD .............................. Mochtar Liibü 7 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE PROMOTION OF JAPANESE- INDONESIAN CULTURAL :RELATIONS ............... Rosihan Anwa-r 12 SMALL FAMILY NORM FOR FILIPINOS.................. F. Landa Jocano 2-4 LIFE STYLE OF THE URBAN POOR AND PEOPLE'S ORGANIZATIONS .................................. Richard P: Poethig 37 NEIGHBORS IN CEBU .................................... Helga E. Jacobson 44 FICTION MOTHER GOES TO HEAVEN.............................. SitorSitumorang 17 BIG WHITE AMERICAN . .. .. .. Federico Licsi Espino, Jr. 30 A CHILD'S GARDEN OF TELEVISION .................... Erwin E. Castillo 35 POETRY TWO POEMS .......................................,........ Trisno Siimci'djo 2 CHINESE IMPRESSIONS: POEMS WRITTEN IN TAIPEI.. Cirilo F. Bautista 22 LIGHT AND DARKNESS MEET TWICE ..........;........ Gemino H. Abad 29 CARISSIMA . .. Tita Lacambra-Ayala 36 THE MANGO TREE ................................... Suvimalee Gunaratna 47 LITERARY NOTES: WRITERS AND AWARDS ........... Federico Mangahas 48 THE PRAYING MAN (Contimiation) .................... Bienvenido N. Santos' 54 INDEX TO VOLUME VI .................................................... 51 CONTRIBUTORS .. .. 51 531 Padre Faura¡ Ermitai Manila¡ Philippines.. Europe and the Amerlcas $.95; Asia Europe and .the Americas S10.00. Asia $8.50. A stamped self-addressed envelope or manuscripts otherwise they carinot be returned. Solidarity is for Cultural Freedom with Office at 104 Boulevard Haussmann Paris Be. Franc-e. Views expressed in Solidarity Magazine are to be attributed to th~ aulhors. Copyright 1967, SOLIDARIDAD Publishing House. ' Entered as Second-Class Matter at the Manila Post Office on February 7, 1968. -

Pustaka-Obor-Indonesia.Pdf

Foreign Rights Catalogue ayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia, a modestly sized philanthropy active in the Yfield of cultural and intellectual development through scholarly publishing. It’s initial focus to publish books from various languages into the Indonesian language. Among its main interest is books on human and democratic rights of the people. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia was set up as an Indonesian legal entity in 1978. The Obor Indonesia office coordinates the careful work of translation and revision. An editorial Board is in charge of program selection. Books are published locally and placed on the market at a low subsidized price within reach of students and the general reader. Obor also plays a service role, helping specialized organizations bring out their research in book form. It is the Purpose of Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia, to widen and develop the perspective of Indonesia’s growing intellectual community, by publishing in Bahasa Indonesia -- and other appropriate languages -- literate and socially significant works. __________________ Contact Detail: Dian Andiani Address: Jl. Plaju No. 10 Jakarta Indonesia 10230 E-mail: [email protected]/[email protected] Web: www.obor.or.id mobile: +6281286494677 2 CATALOGUE Literature CATALOGUE 3 Harimau!Harimau!|Tiger! Tiger! Author: Mochtar Lubis | ISBN: 978-979-461-109-8 | “Tiger! Tiger!” received an award from ‘Buku Utama’ foundation as the best literature work in 1975. This book illustrated an adventurous story in wild jungle by a group of resin collector who was hunted by a starving tiger. For days, they tried to escape but they became victims. The tiger pounced on them one by one. -

Heirs to World Culture DEF1.Indd

14 The capital of pulp fiction and other capitals Cultural life in Medan, 1950-1958 Marije Plomp The general picture of cultural activities in Indonesia during the 1950s emanating from available studies is based on data pertain- ing to the nation’s political and cultural centre,1 Jakarta, and two or three other main cities in Java (Foulcher 1986; Rhoma Dwi Aria Yuliantri and Muhidin M. Dahlan 2008). Other regions are often mentioned only in the framework of the highly politicized debate on the outlook of an Indonesian national culture that had its origins in the 1930s (Foulcher 1986:32-3). Before the war, the discussions on culture in relation to a nation were anti-colonial and nationalistic in nature, but after Independence the focus shifted. Now the questions were whether or not the regional cul- tures could contribute to a modern Indonesian national culture, and how they were to be valued vis-à-vis that national culture. What cultural life in one of the cities in the outer regions actually looked like, and what kind of cultural networks – national, trans- national and transborder – existed in the various regions has yet to be researched. With this essay I aim to contribute to a more differentiated view on the cultural activities in Indonesia in the 1950s by charting a part of the cultural world of Medan and two of its (trans)national and transborder cultural exchange networks in the period 1950- 1958. This time span covers the first eight years of Indonesia as an independent nation until the start of the insurrection against the central army and government leaders by North Sumatran army commander Colonel Maludin Simbolon on 22 December 1958 (Conboy 2003:37-51).