Soares, F. (2017) 'The Titles 'King of Sumer and Akkad'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Writing the History of Southern Mesopotamia* by Eva Von

On Writing the History of Southern Mesopotamia* by Eva von Dassow — Colorado State University In his book Babylonia 689-627 B.C., G. Frame provides a maximally detailed his- tory of a specific region during a closely delimited time period, based on all available sources produced during that period or bearing on it. This review article critiques the methods used to derive the history from the sources and the conceptual framework used to apprehend the subject of the history. Babylonia 689-627 B. C , the revised version of Grant Frame's doc- toral dissertation, covers one of the most turbulent and exciting periods of Babylonian history, a time during which Babylon succes- sively experienced destruction and revival at Assyria's hands, then suf- fered rebellion and siege, and lastly awaited the opportunity to over- throw Assyria and inherit most of Assyria's empire. Although, as usual, the preserved textual sources cover these years unevenly, and often are insufficiently varied in type and origin (e.g., royal or non- royal, Babylonian or Assyrian), the years from Sennacherib's destruc- tion of Babylon in 689 to the eve of Nabopolassar's accession in 626 are also a richly documented period. Frame's work is an attempt to digest all of the available sources, including archaeological evidence as well as texts, in order to produce a maximally detailed history. Sur- rounding the book's core, chapters 5-9, which proceed reign by reign through this history, are chapters focussing on the sources (ch. 2), chronology (ch. 3), the composition of Babylonia's population (ch. -

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

The Last Days of the Kingdom of Israel

The Last Days of the Kingdom of Israel Edited by Shuichi Hasegawa, Christoph Levin and Karen Radner Unauthenticated Download Date | 11/6/18 2:50 PM ISBN 978-3-11-056416-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-056660-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-056418-1 ISSN 0934-2575 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hasegawa, Shuichi, 1971- editor. | Levin, Christoph, 1950- editor. | Radner, Karen, editor. Title: The last days of the Kingdom of Israel / edited by Shuichi Hasegawa, Christoph Levin, Karen Radner. Description: First edition. | Berlin; Boston : Walter de Gruyter, [2018] | Series: Beihefte zur Zeitschrift fur die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, ISSN 0934-2575 ; Band 511 Identifiers: LCCN 2018023384 | ISBN 9783110564167 Subjects: LCSH: Jews--History--953-586 B.C. | Assyria--History. | Bible. Old Testament--Criticism, interpretation, etc. | Assyro-Babylonian literature--History and criticism. Classification: LCC DS121.6 .L37 2018 | DDC 933/.03--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn. loc.gov/2018023384 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliografic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Unauthenticated Download Date | 11/6/18 2:50 PM Table of Contents Shuichi Hasegawa The Last Days of the Northern Kingdom of Israel Introducing the Proceedings of a Multi-Disciplinary Conference 1 Part I: Setting -

Ancient Mesopotamia Akkdadian Empire Reading Comprehension

ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA AKKDADIAN EMPIRE READING COMPREHENSION *Article *10 Matching Questions *10 True/False Questions *4 Multiple Choice Questions *Key Included Name____________________ ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA- AKKADIAN EMPIRE The Akkadian Empire was the first Empire to rule all of Mesopotamia. It lasted about 200 years from 2300 BC to 2100 BC. Originally the Sumerians lived in the southern part of Mesopotamia and the Akkadians lived in the northern part. They had similar governments and cultures, but spoke different languages. The governments had individual city-states, where each city had its own ruler that controlled the city and the surrounding area. The city-states were not initially united and often warred with one another. Eventually, the Akkadian rulers started to see the advantage to uniting many of their cities under a single nation and began forming alliances to work together. Sargon the Great rose to power around 2300 BC. According to Sumerian literature, Sargon was born to an Akkadian high priestess and a poor father, maybe a gardener. His mother abandoned him by putting him a reed woven basket and let it float down the river, like Moses a thousand years later. Sargon was rescued and made friends with the goddess Ishtar and was brought up in the king’s court. Sargon built himself a new city at Akkad and made himself the king of it when he grew up. He gradually conquered all the land around it, making the Akkadian Empire. The powerful Sumerian city of Uruk attacked Akkad, but they fought back and eventually conquered Uruk. Sargon went on to conquer all of the Sumerian city-states and united northern and southern Mesopotamia under a single ruler. -

SUMERIAN LITERATURE and SUMERIAN IDENTITY My Title Puts

CNI Publicati ons 43 SUMERIAN LITERATURE AND SUMERIAN IDENTITY JERROLD S. COOPER PROBLEMS OF C..\NONlCl'TY AND IDENTITY FORMATION IN A NCIENT EGYPT AND MESOPOTAMIA There is evidence of a regional identity in early Babylonia, but it does not seem to be of the Sumerian ethno-lingusitic sort. Sumerian Edited by identity as such appears only as an artifact of the scribal literary KIM RYHOLT curriculum once the Sumerian language had to be acquired through GOJKO B AR .I AMOVIC educati on rather than as a mother tongue. By the late second millennium, it appears there was no notion that a separate Sumerian ethno-lingui stic population had ever existed. My title puts Sumerian literature before Sumerian identity, and in so doing anticipates my conclusion, which will be that there was little or no Sumerian identity as such - in the sense of "We are all Sumerians!" outside of Sumerian literature and the scribal milieu that composed and transmitted it. By "Sumerian literature," I mean the corpus of compositions in Sumerian known from manuscripts that date primarily 1 to the first half of the 18 h century BC. With a few notable exceptions, the compositions themselves originated in the preceding three centuries, that is, in what Assyriologists call the Ur III and Isin-Larsa (or Early Old Babylonian) periods. I purposely eschew the too fraught and contested term "canon," preferring the very neutral "corpus" instead, while recognizing that because nearly all of our manuscripts were produced by students, the term "curriculum" is apt as well. 1 The geographic designation "Babylonia" is used here for the region to the south of present day Baghdad, the territory the ancients would have called "Sumer and Akkad." I will argue that there is indeed evidence for a 3rd millennium pan-Babylonian regional identity, but little or no evidence that it was bound to a Sumerian mother-tongue community. -

AP World History the Epic of Gilgamesh Considering the Evidence

AP World History The Epic of Gilgamesh August 17, 2011 Considering the Evidence: Life and Afterlife in Mesopotamia and Egypt The advent of writing was not only a central The epic poem itself recounts the adventures of feature of the First Civilizations but also a great Gilgamesh, said to he part human and part divine. boon to later historians. Access to early written As the story opens, he is the energetic and yet records from these civilizations allows us some oppressive ruler of Uruk. The pleas of his people insight, in their own words, as to how these persuade the gods to send Enkidu, an uncivilized ancient peoples thought about their societies and man from the wilderness, to counteract this their place in the larger scheme of things. Such oppression. But before he can confront the erring documents, of course, tell only a small part of the monarch, Enkidu must become civilized, a process story, for they most often reflect the thinking of that occurs at the hands of a seductive harlot. the literate few—usually male, upper-class, When the two men finally meet, they engage in a powerful, and well-to-do—rather than the outlook titanic wrestling match from which Gilgamesh of the vast majority who lacked such privileged emerges victorious. Thereafter they bond in a deep positions. Nonetheless, historians have been friendship and undertake a series of adventures grateful for even this limited window on the life of together. In the course of these adventures, they at least some of our ancient ancestors. offend the gods, who then determine that Enkidu must die. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Neo-Assyrian Period 934–612 BC the Black Obelisk

Map of the Assyrian empire up to the reign of Sargon II (721–705 BC) Neo-Assyrian period 934–612 BC The history of the ancient Middle East during the first millennium BC is dominated by the expansion of the Assyrian state and its rivalry with Babylonia. At its height in the seventh century BC, the Assyrian empire was the largest and most powerful that the world had ever known; it included all of Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, as well as parts of Anatolia and Iran. Ceramics with very thin, pale fabric, referred to as Palace Ware, were the luxury ware of the Assyrians. Glazed ceramics are also characteristically Neo-Assyrian in form and decoration. The Black Obelisk Excavated by Austin Henry Lanyard in 1845 at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), the black limestone sculpture known as the Black Obelisk commemorates the achievements of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (858–824 BC); a cast of the monument stands today in the Dr. Norman Solhkhah Family Assyrian Empire Gallery (C224–227) at the OI Museum. Twenty relief panels, distributed in five rows on the four sides of the obelisk, show the delivery of tribute from subject peoples and vassal kings (a king that owes loyalty to another ruler). A line of cuneiform script below each identifies the tribute and source. The Assyrian king is shown in two panels at the top, first depicted as a warrior with a bow and arrow, receiving Sua, king of Gilzanu (northwestern Iran); and second, as a worshiper with a libation bowl in hand, receiving Jehu, king of the House of Omri (ancient northern Israel). -

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

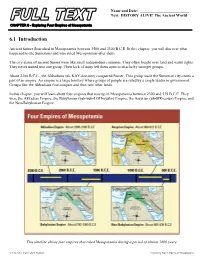

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE Period Overview The Ancient Sumer civilization grew up around the Euphretes and Tigris rivers in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), because of its natural fertility. It is often called the ‘cradle of civilization’. By 3000BCE the area was inhabited by 12 main city states, with most developing a monarchical system. The fertility of the soil in the area allowed the societies to devote their attention to other things, and so the Sumer is renowned for its innovation. The clock system we use today of 60-minute hours was devised by Ancient Sumerians, as was writing and the recording of a number system. The civilization began to decline after the invasion of the city states by Sargon I in around 2330BCE, bringing them into the Akkadian Empire. A later Sumerian revival occurred in the area. Life in Ancient Sumer Changing Times Although starting out as small villages and groups of During the 5th Millennium BCE, Sumerians began to hunter-gatherers, Sumer is notable because of its develop large towns which became city-states. This development into a chain of cities. Within the cities the was made by possible by their systems of cultivation of advantages of communal living soon allowed crops, including some of the world’s earliest irrigation individuals to take on other roles than farming, and a systems. These developing communities then were society of classes developed. At the top of the class able to devote time to pursuits other than gathering system were the king and his family, and the priests.