The Last Days of the Kingdom of Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

Neo-Assyrian Period 934–612 BC the Black Obelisk

Map of the Assyrian empire up to the reign of Sargon II (721–705 BC) Neo-Assyrian period 934–612 BC The history of the ancient Middle East during the first millennium BC is dominated by the expansion of the Assyrian state and its rivalry with Babylonia. At its height in the seventh century BC, the Assyrian empire was the largest and most powerful that the world had ever known; it included all of Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, as well as parts of Anatolia and Iran. Ceramics with very thin, pale fabric, referred to as Palace Ware, were the luxury ware of the Assyrians. Glazed ceramics are also characteristically Neo-Assyrian in form and decoration. The Black Obelisk Excavated by Austin Henry Lanyard in 1845 at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), the black limestone sculpture known as the Black Obelisk commemorates the achievements of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (858–824 BC); a cast of the monument stands today in the Dr. Norman Solhkhah Family Assyrian Empire Gallery (C224–227) at the OI Museum. Twenty relief panels, distributed in five rows on the four sides of the obelisk, show the delivery of tribute from subject peoples and vassal kings (a king that owes loyalty to another ruler). A line of cuneiform script below each identifies the tribute and source. The Assyrian king is shown in two panels at the top, first depicted as a warrior with a bow and arrow, receiving Sua, king of Gilzanu (northwestern Iran); and second, as a worshiper with a libation bowl in hand, receiving Jehu, king of the House of Omri (ancient northern Israel). -

Israel Taken Captive

Unit 14 • Session 3 Use Week of: Unit 14 • Session 3 Israel Taken Captive BIBLE PASSAGE: 2 Kings 17 STORY POINT: Israel ignored God’s prophets and was captured. KEY PASSAGE: 2 Peter 3:9 BIG PICTURE QUESTION: Why should we obey God? We should obey God because He made us, He loves us, and His plans are good. INTRODUCE THE STORY TEACH THE STORY APPLY THE STORY (10–15 MINUTES) (25–30 MINUTES) (25–30 MINUTES) PAGE 108 PAGE 110 PAGE 116 Additional resources are available at gospelproject.com. For free training and session-by- session help, visit MinistryGrid.com/gospelproject. Younger Kids Leader Guide 104 Unit 14 • Session 3 LEADER Bible Study God’s people had a history of disobeying God. Sin separated them from God. But man was created to know and love God, and God was working out a plan to bring His children back to Himself. Like any good father, God knows that disobedience needs to be punished. “The Lord disciplines the one he loves, just as a father disciplines the son in whom he delights” (Prov. 3:12). After the tribes of Israel split into the Northern Kingdom and Southern Kingdom, God sent prophets to both kingdoms to warn the people to turn from their sins and obey God. Over the course of 200 years, the prophets Elijah, Elisha, Jonah, Amos, and Hosea spoke to Israel and warned them of the consequences of their idolatry. They called for Israel to repent and turn back to God. But Israel did not listen. 3 God had been very patient with the Israelites. -

Kalhu/Nimrud: Cities and Eyes

Kalhu/Nimrud/CalahKalhu/Nimrud/Calah Cities and Eyes Noah Wiener Location Site Layout Patti-Hegalli Canal Chronology • Shalmaneser I 1274-1275 BCE • Assurnasirpal II 884-859 BCE • Shalmaneser III 859-824 BCE • Samsi-Adad V 824-811 BCE • Adad-nerari III (Shammuramat) 811-783 BCE • Tiglath-pileser III 745-727 BCE • Shalmaneser V 727-722 BCE • Sargon II 722-705 BCE • (Destruction of Nimrud 612 BCE) Assurnasirpal II • Moved capital to Kalhu, opening city with lavish feasts and celebration in 879 BCE. • Strongly militaristic, known for brutality. Captives built much of Kalhu. • Military campaigns through Syria made him the first Assyrian ruler in centuries to extend boundaries to the Mediterranean through the Levant Shalmaneser III •• CCoonnssttrruucctteedd NNiimmrruudd’’ss ZZiigggguurraatt aanndd FFoorrtt SShhaallmmaanneesseerr •• MMiilliittaarriissttiicc,, ‘‘ddeeffeeaatteedd’’ DDaammaassccuuss’’ aalllliiaannccee,, JJeehhuu ooff IIssrraaeell,, TTyyrree,, aanndd mmaannyy nneeiigghhbboorriinngg ssttaatteess •• RReeiiggnn eennddeedd iinn rreevvoolluuttiioonn • Samsi-Adad V– ended revolution, invaded Babylon • Adad-nerari III– Young King, siege in Damascus, during early years mother acted as regent. • (Period of decline) • Tiglath-Pileser III– Extremely successful conqueror, greatly extended Assyrian power. Built Central Palace, reformed Assyrian army and removed power of many officials. • Shalmaneser V– Heavy taxation leading to rebellion. • Sargon II– Successful ruler, moved capital from Kalhu. Archaeology • Austen Henry Layard 1817-1895 • Sir Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan 1904-1978 The Northwest Palace The Northwest Palace The Northwest Palace The Northwest Palace South West and Central Palaces Ziggurat Temples Fort Shalmaneser Fort Shalmaneser Residential Kalhu Two Types of Tomb Finds at Kalhu Finds at Kalhu Finds at Kalhu. -

Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire Steven W

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Libraries Libraries & Educational Technologies 2001 Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire Steven W. Holloway James Madison University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/letfspubs Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation “Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire,” Journal of Religion & Society (http://moses.creighton.edu/jrs/2001/ 2001-12.pdf) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries & Educational Technologies at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Libraries by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Religion & Society Volume 3 (2001) ISSN 1522-5658 Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire Steven W. Holloway, American Theological Library Association and Saint Xavier University, Chicago Abstract The successful “invasion” of ancient Mesopotamia by explorers in the pay of the British Museum Trustees resulted in best-selling publications, a treasure-trove of Assyrian antiquities for display purposes and scholarly excavation, and a remarkable boost to the quest for confirmation of the literal truth of the Bible. The public registered its delight with the findings through the turnstyle- twirling appeal of the British Museum exhibits, and a series of appropriations of Assyrian art motifs and narratives in popular culture - jewelry, bookends, clocks, fine arts, theater productions, and a walk-through Assyrian palace among other period mansions at the Sydenham Crystal Palace. -

2 KINGS (Teacher's Edition)

2 KINGS (Teacher’s Edition) Part One: The Divided Kingdom (1:1--17:41) I. The Reign of Ahaziah in Israel 1 II. The Reign of Jehoram in Israel 2:1--8:15 III. The Reign of Jehoram in Judah 8:16-24 IV. The Reign of Ahaziah in Judah 8:25--9:29 V. The Reign of Jehu in Israel 9:30--10:36 VI. The Reign of Queen Athaliah in Judah 11:1-16 VII. The Reign of Joash in Judah 11:17--12:21 VIII. The Reign of Jehoahaz in Israel 13:1-9 IX. The Reign of Jehoash in Israel 13:10-25 X. The Reign of Amaziah in Judah 14:1-22 XI. The Reign of Jeroboam II in Israel 14:23-29 XII. The Reign of Azariah in Judah 15:1-7 XIII. The Reign of Zechariah in Israel 15:8-12 XIV. The Reign of Shallum in Israel 15:13-15 XV. The Reign of Menahem in Israel 15:16-22 XVI. The Reign of Pekahiah in Israel 15:23-26 XVII. The Reign of Pekah in Israel 15:27-31 XVIII. The Reign of Jotham in Judah 15:32-38 XIX. The Reign of Ahaz in Judah 16 XX. The Reign of Hoshea in Israel 17 Part Two: The Surviving Kingdom of Judah (18:1--25:30) I. The Reign of Hezekiah in Judah 18:1--20:21 II. The Reign of Manasseh in Judah 21:1-18 III. The Reign of Amon in Judah 21:19-26 IV. The Reign of Josiah in Judah 22:1--23:30 V. -

H 02-UP-011 Assyria Io02

he Hebrew Bible records the history of ancient Israel reign. In three different inscriptions, Shalmaneser III and Judah, relating that the two kingdoms were recounts that he received tribute from Tyre, Sidon, and united under Saul (ca. 1000 B.C.) Jehu, son of Omri, in his 18th year, tand became politically separate fol- usually figured as 841 B.C. Thus, Jehu, lowing Solomon’s death (ca. 935 B.C.). the next Israelite king to whom the The division continued until the Assyrians refer, appears in the same Assyrians, whose empire was expand- order as described in the Bible. But he ing during that period, exiled Israel is identified as ruling a place with a in the late eighth century B.C. different geographic name, Bit Omri But the goal of the Bible was not to (the house of Omri). record history, and the text does not One of Shalmaneser III’s final edi- shy away from theological explana- tions of annals, the Black Obelisk, tions for events. Given this problem- contains another reference to Jehu. In atic relationship between sacred the second row of figures from the interpretation and historical accura- top, Jehu is depicted with the caption, cy, historians welcomed the discovery “Tribute of Iaua (Jehu), son of Omri. of ancient Assyrian cuneiform docu- Silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden ments that refer to people and places beaker, golden goblets, pitchers of mentioned in the Bible. Discovered gold, lead, staves for the hand of the in the 19th century, these historical king, javelins, I received from him.”As records are now being used by schol- scholar Michele Marcus points out, ars to corroborate and augment the Jehu’s placement on this monument biblical text, especially the Bible’s indicates that his importance for the COPYRIGHT THE BRITISH MUSEUM “historical books” of Kings. -

Notes on 2 Kings 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on 2 Kings 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Second Kings continues the narrative begun in 1 Kings. It opens with the translation of godly Elijah to heaven and closes with the transportation of the ungodly Jews to Babylon. For discussion of title, writer, date, scope, purpose, genre, style, and theology of 2 Kings, see the introductory section in my notes on 1 Kings. OUTLINE (Continued from notes on 1 Kings) 3. Ahaziah's evil reign in Israel 1 Kings 22:51—2 Kings 1:18 (continued) 4. Jehoram's evil reign in Israel 2:1—8:15 5. Jehoram's evil reign in Judah 8:16-24 6. Ahaziah's evil reign in Judah 8:25—9:29 C. The second period of antagonism 9:30—17:41 1. Jehu's evil reign in Israel 9:30—10:36 2. Athaliah's evil reign in Judah 11:1-20 3. Jehoash's good reign in Judah 11:21—12:21 4. Jehoahaz's evil reign in Israel 13:1-9 5. Jehoash's evil reign in Israel 13:10-25 6. Amaziah's good reign in Judah 14:1-22 7. Jeroboam II's evil reign in Israel 14:23-29 8. Azariah's good reign in Judah 15:1-7 9. Zechariah's evil reign in Israel 15:8-12 10. Shallum's evil reign in Israel 15:13-16 11. Menahem's evil reign in Israel 15:17-22 12. Pekahiah's evil reign in Israel 15:23-26 13. Pekah's evil reign in Israel 15:27-31 Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. -

The Hebrew Myths and the Neo Assyrian Empire

The Hebrew Myths and the Neo-Assyrian Empire. by Benjamín Toro A dissertation submitted to University of Birmingham for the degree of MPhil (B) in Cuneiform Studies. Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity School of Historical Studies University of Birmingham 16 January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. INFORMATION FOR ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING SERVICES The information on this form will be published. Surname: Toro First names: Benjamin Degree: MPhil (B) in Cuneiform Studies College/Department: Institute of Antiquities and Archaeology. Full title of thesis: The Hebrew Myths and the New Assyrian Empire. Date of submission: 16/01/2011 Date of award of degree (leave blank): Abstract (not to exceed 200 words - any continuation sheets must contain the author's full name and full title of the thesis): This project seeks to study the first expression of Israelite literature which would was elaborated under the shadow of the Neo-Assyrian cultural influence. This occurred approximately between the 9th to 8th centuries BCE, before a transformation triggered off by theological viewpoints held in the southern kingdom of Judah between the 7th to 6th centuries BCE. -

A List of Babylonian Kings

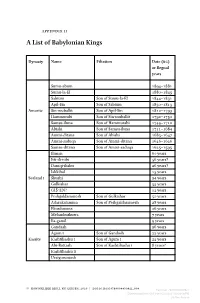

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody -

KARUS on the FRONTIERS of the NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo

KARUS ON THE FRONTIERS OF THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo YAMADA * The paper discusses the evidence for the harbors, trading posts, and/or administrative centers called karu in Neo-Assyrian documentary sources, especially those constructed on the frontiers of the Assyrian empire during the ninth to seventh centuries Be. New Assyrian cities on the frontiers were often given names that stress the glory and strength of Assyrian kings and gods. Kar-X, i.e., "Quay of X" (X = a royal/divine name), is one of the main types. Names of this sort, given to cities of administrative significance, were probably chosen to show that the Assyrians were ready to enhance the local economy. An exhaustive examination of the evidence relating to cities named Kar-X and those called karu or bit-kar; on the western frontiers illustrates the advance of Assyrian colonization and trade control, which eventually spread over the entire region of the eastern Mediterranean. The Assyrian kiirus on the frontiers served to secure local trading activities according to agreements between the Assyrian king and local rulers and traders, while representing first and foremost the interest of the former party. The official in charge of the kiiru(s), the rab-kari, appears to have worked as a royal deputy, directly responsible for the revenue of the royal house from two main sources: (1) taxes imposed on merchandise and merchants passing through the trade center(s) under his control, and (2) tribute exacted from countries of vassal status. He thus played a significant role in Assyrian exploitation of economic resources from areas beyond the jurisdiction of the Assyrian provincial government. -

Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah As Seen Through the Assyrian Lens

Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah as Seen Through the Assyrian Lens: A Commentary on Sennacherib’s Account of His Third Military Campaign with Special Emphasis on the Various Political Entities He Encounters in the Levant Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Paul Downs, B.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2015 Thesis Committee: Dr. Sam Meier, Advisor Dr. Kevin van Bladel Copyright by Paul Harrison Downs 2015 2 Abstract In this thesis I examine the writings and material artifacts relevant to Sennacherib’s third military campaign into the regions of Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah. The intent of this examination is to investigate the political, ethnic, and religious entities of the ancient Levant from an exclusively Assyrian perspective that is contemporary with the events recorded. The focus is to analyze the Assyrian account on its own terms, in particular what we discover about various regions Sennacherib confronts on his third campaign. I do employ sources from later periods and from foreign perspectives, but only for the purpose of presenting a historical background to Sennacherib’s invasion of each of the abovementioned regions. Part of this examination will include an analysis of the structural breakdown of Sennacherib’s annals (the most complete account of the third campaign) to see what the structure of the narrative can tell us about the places the Assyrians describe. Also, I provide an analysis of each phase of the campaign from these primary writings and material remains.