CIDSE / CI – Submission to World Bank / IMF 2005 PRS Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Persone E Il Pianeta Al Primo Posto: L’Imperativo Di Cambiare Rotta” (Roma, 2-3 Luglio 2015)

N. 0525 Mercoledì 01.07.2015 Conferenza Stampa per presentare la Conferenza di alto livello “Le persone e il pianeta al primo posto: l’imperativo di cambiare rotta” (Roma, 2-3 luglio 2015) Intervento del Card. Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson Intervento della Sig.ra Naomi Klein Intervento del Prof. Ottmar Edenhofer Intervento del Sig. Bernd Nilles Campagna su un nuovo stile di vita sostenibile: “Change for the Planet - Care for the People” Scheda Informativa sulla CIDSE Alle ore 11.30 di questa mattina, nell’Aula Giovanni Paolo II della Sala Stampa della Santa Sede si tiene una Conferenza stampa per presentare la Conferenza di alto livello “Le persone e il pianeta al primo posto: l’imperativo di cambiare rotta”, che terrà i suoi lavori domani e dopodomani all’Augustinianum (Roma), organizzata dal Pontificio Consiglio della Giustizia e della Pace e dalla CIDSE (rete internazionale di Ong cattoliche per lo Sviluppo). Intervengono alla Conferenza stampa: la Sig.ra Naomi Klein, Scrittrice; il Prof. Ottmar Edenhofer, Co-Chair del Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); il Sig. Bernd Nilles, Segretario Generale della International Alliance of Catholic Development Organisations (CIDSE). L’intervento del Card. Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson, Presidente del Pontificio Consiglio della Giustizia e della Pace, non presente alla conferenza stampa, è letto dalla Dott.ssa Flaminia Giovanelli, Sotto-Segretario del medesimo Dicastero. Pubblichiamo di seguito gli interventi dei conferenzieri, un testo sulla Campagna della CIDSE su un nuovo stile 2 di vita sostenibile e una scheda informativa sulla CIDSE: Intervento del Card. Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson The Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace is happy to join CIDSE, the international alliance of 17 Catholic Development Organisations, in hosting the international conference “People and Planet First: the Imperative to Change Course” here in Rome, 2-3 July 2015. -

To All Superiors General T O a L L D E L E G a T E S F O R SEDOS To

Mil - Zi, 71/31 Eome, 15 October" 1971 To all Superiors General To all delegates for SEDOS To all members of the SEDOS Group A tous les Superieurs Gen^raux A tous les d^legu^s de SEDOS A tous les membres de SEDOS This week! Cette semaines 1 , HEWS FEOM AND FOR THE GENERALATES NOUVELLES DES ET POUR LES GENER, 658 2o DOCUMENTS OF SPECIAL INTEREST DOCUMENTS D'INTERET SPECIAL 659 3o HEALTH GROUP - TASK FORCE MEETING REUNION DU GRo MEDICAL "TASK FORCE" 661 4o LISTS OF PERIODICALS RECEIVED LISTES DES DOCUMENTS RECUS 663 5. THE SITUATION - WORLD COUNCIL OF CHJECHES LA SITUATIONS- LE COINISEIL OSCUM. 666 CoVoM.E, COMMITTEE - Montreux 1971 D«M,Eo - ^fontreux 1971 6. DIARY CHEONIQUE 674 Yours S incerely Fro Leonzio Bano, fscj SEDOS 71/658 NEWS FROM AND FOR THE GENERALATES ) 0° Carmelites - The General Chapter being held in Rome elected the new General Coxincil. Superior General; Fro Falco Thuis, 0, Carmo Councillors: Fr* S. Possanzini Fr* Sean Coughlan Fro Vo Brig Fr. Go Cardoso 2) Xaverian Missionaries - The General Chapter of the Xaverian Missionaries at Parma renewed their General Coimcilo Superior General; Mgr* Giovanni Gazza Coimcillors: Fr. Po Robert Maloney, Vicar General Fr. Go Ferrari, Missions Secretary Fro A. Paolucci, Bursar General Fr. L. Piacere, Formation Secretary 3) Broo H« Boyle CFX, Superior General of the Xaverian Brothers, is leaving for a two month visit to the United States. 4) INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION - Vienna Another expert available through the Vienna organisation for service in a develop ing country: (Bull. No. 71/29 p.61 7): Miss MARIE CERVIHOVA, 36, Czech Agricultural University, Plant Production. -

Global Initiative Sought for Protection of Christians

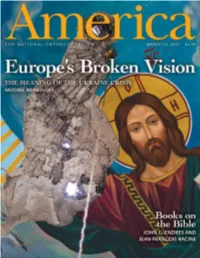

OF MANY THINGS he work of John Courtney “Unfortunately, this instrument has 106 West 56th Street New York, NY 10019-3803 Murray, S.J., once an associate become blunt,” he has said. Benedict Ph: 212-581-4640; Fax: 212-399-3596 editor of this review, continues believes that when considering the Subscriptions: 1-800-627-9533 T www.americamagazine.org to dominate political theology in the natural law tradition in a political facebook.com/americamag United States. Most students of Father context, one must account for the fact twitter.com/americamag Murray turn first toWe Hold These that, among modern thinkers, it is an , Murray’s most accomplished open question whether “there might PRESIDENT AND EDITOR IN CHIEF Truths Matt Malone, S.J. and well-known articulation of his exist a rationality of nature and, hence, a EXECUTIVE EDITORS principal thesis: that Catholicism and rational law for man and for his existence Robert C. Collins, S.J., Maurice Timothy Reidy American democracy are essentially in the world.” MANAGING EDITOR Kerry Weber compatible “because the contents of [the I would add that part of the reason LITERARY EDITOR Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. American public] consensus—the ethical why natural law theory is effectively SENIOR EDITOR AND CHIEF CORRESPONDENT and political principles drawn from a “blunt instrument” is that it has Kevin Clarke the tradition of natural law—approve been detached from its theological EDITOR AT LARGE James Martin, S.J. themselves to the Catholic intelligence presuppositions in the misguided and EXECUTIVE EDITOR, AMERICA FIlmS Jeremy Zipple, S.J. and conscience.” vain hope of rendering it more “credible” POETRY EDITOR Joseph Hoover, S.J. -

Climate Action Call

Scientists say that we face a climate emergency. We need decisive action in the next 10 years to put us on a transformative pathway in line with the targets of the Paris Agreement, including efforts to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. We must act immediately to get on track for a healthy, fair and liveable future. This will not only reduce devastating impacts of climate change but also bring major economic and social benefits, attract new investments, create new quality jobs and limit health damages. The European Parliament elections and subsequent changes in the leadership of the European Commission will shape the politics of the European Union for the next five years, a crucial period for climate action where emissions need to decline fast, targets need to be strengthened and ambitious action needs to be implemented. The new Parliament and the new Commission must address growing concerns about climate change and make climate action a top priority for Europe. Therefore, we call upon the new European Parliament, the new European Commission and all EU Member State governments to: 1. Commit to accelerate actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and reach net zero emissions as soon as possible. The world is not on track to keep temperature rise to 1.5°C. We support the call from United Nations Secretary General António Guterres, upon all leaders to come to his special UN Climate Summit in September with additional commitments that will lead to halving global emissions by 2030 and achieving net zero by 2050. By the Summit, EU leaders should agree to reach climate neutrality in line with the EU’s fair share of the effort to achieve net zero global emissions by 2050. -

A Call for a Month of Climate Action: the Faithful Respond to the Bishops' COP21 Appeal

October 29, 2015 A Call for a Month of Climate Action: the Faithful Respond to the Bishops' COP21 Appeal As we announce the launch of the “Month of Climate Action," the 200 member organizations of the Global Catholic Climate Movement (GCCM) thank and support the Bishops of the Church for their COP21 Appeal. "Our common home is being pillaged, laid waste and harmed with impunity. Cowardice in defending it is a grave sin ... People and their movements are called to cry out, to mobilize and to demand—peacefully, but firmly—that appropriate and urgentlyneeded measures be taken. I ask you, in the name of God, to defend Mother Earth." Pope Francis, Speech at World Meeting of Popular Movements, 9.07.2015. “We, Cardinals, Patriarchs and Bishops ... call on COP 21 to forge an international agreement to limit a global temperature increase to within those parameters currently suggested from within the global scientific community to avoid catastrophic climatic impacts, especially on the poorest and most vulnerable communities...” Bishops’ Appeal to COP21 Negotiating Parties. In one month, international leaders will gather in Paris for the 21st Session of the Conference of Parties (COP21) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. They will once again debate responses to the crises and causes of climate change. And we will be expecting and demanding appropriate action. On the eve of this critical moment in history, the Global Catholic Climate Movement (GCCM) announces its “Month of Climate Action” We unite in prayer and activism with all Catholics who insist that COP21 produce sound climate policies—ones that encourage lifestyles rooted in solidarity, charity, and justice, the natural limits of our common home, and acknowledgement of the need to protect shared resources crucial for life. -

«The Time for Conversion Is Now...»

World peace cannot be safeguarded without the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences making of creative efforts proportionate to the of the European Community dangers which threaten it. The contribution which an organized and living Europe can bring to civilization is indispensable to the maintenance of peaceful relations. In taking upon herself for more than 20 years the role of champion of a united Europe, France- has always had as her essential aim the service of peace. A united Europe was not achieved and we had war. Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which �irst create a de facto solidarity. The coming together of the nations of Europe - requires the elimination of the age-old opposition of France and Germany. Any action taken must in the �irst place concern these two countries. With this aim in view, the French Government proposes that action be taken immediately on one limited but decisive point. It proposes that Franco-German produc tion of coal and steel as a whole be placed under a common High Authority, within the framework of an organization open to the participation of the other countries of Europe. The pooling of coal and steel production should immediately provide for the setting up of common foundations for economic deve lopment as a �irst step in the federation of Europe, and will change the destinies of those regions which have long been devoted to the manufacture of munitions of war, of which they have been the most - constant victims. -

Annual Report 2018 CONTENTS

Annual Report 2018 CONTENTS FOREWORD FROM THE PRESIDENT 3 TIMELINE 4 AREAS OF WORK 9 » Systemic change » Gender equality » Laudato Si’ » Business and human rights » Alternatives to extractives » Land rights » Israel & the occupied Palestinian territory » Resilient food systems » COP24 » Energy » Change for the Planet – Care for the People COMING UP 21 GOVERNANCE STRUCTURES AND FINANCE 22 ABOUT CIDSE 26 Cover page photo © Schröder - MISEREOR FOREWORD FROM THE PRESIDENT In 2018, the president All our priorities ran of CIDSE was my at full speed ahead: we predecessor Eamonn launched a multimedia © len project on agroecology, Meehan who led Broederlijk De our organisation for an carried out a directors’ exciting year full of activities visit to Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory. We continued to but marked specially by COP24 in develop our approach to gender equality, Katowice, Poland. and to put forward innovative proposals It was a big moment for our sustainable for addressing energy poverty and climate lifestyles campaign “Change for The mitigation and resilience. Planet – Care for the People” as a unique With our strong presence and engagement time and place in which to unite our at the World Social Forum and the volunteers. Thematic Social Forum on mining and extractives, we continued to explore Many of them spoke later of their time with social movements how we can best in Katowice as a turning point for them support and amplify their inspiring work. – how it was the first time they attended a political demonstration for climate, or Our advocacy work in the field of business they heard a moving story that opened and human rights continued to rely on them to a new perspective on the issue. -

PRESS RELEASE Amazon Synod Is a Providential Opportunity To

PRESS RELEASE Amazon Synod is a providential opportunity to denounce oppressive global structures, inequalities, and the climate emergency • CIDSE member organisations have worked in the Amazon for decades and see in this part of the world a clear case for systemic change and toward integral ecology, because this area has suffered all of the most common patterns of social and environmental injustice. The whole world is connected to the Amazon, hopefully the first of other biomes in Africa and Asia to be recognised for special protection from destruction. • The Catholic community is alarmed over rising deforestation, extractivism and the plight of the Amazon’s Indigenous people and their territories and sees the Synod as a prophetic summit about the future of these communities and the future of the whole planet. • Among the special guests inside the Synod, Josianne Gauthier, Secretary General of CIDSE is one of the few women to be present in the Assembly, along with Msrg. Pirmin Spiegel, Director General of MISEREOR, CIDSE’s German member. Brussels, 1 October 2019. CIDSE and its member organisations (MOs), present and active in the Amazon region for decades with longstanding collaboration with allies and partners in all nine countries of the region, working with hundreds of projects in solidarity with the most vulnerable communities, welcome the Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon Region: New Paths for the Church and an Integral Ecology (Rome, 6-27 October 2019). This important gathering aims to put at the centre of the Church’s reflection the lives of 34 million people, as well as the protection of all forms of life in this region and its biodiversity, as a key contribution to the care of our common home. -

Holy See Representative Reminds COP19 Climate Negotiators That Human Survival Is at Stake, Commissioner Hedegaard Warns of “Business As Usual”

CIDSE press release, Warsaw, 19 November 2013 Holy See representative reminds COP19 climate negotiators that human survival is at stake, Commissioner Hedegaard warns of “business as usual” CIDSE, an international alliance of Catholic development organisations, heard dire warnings of climate change at a Warsaw conference with top-level speakers, including European Commissioner Hedegaard, Head of Holy See Delegation and Nuncio to Poland Archbishop Migliore, Scottish Minister of Environment and Climate Change Wheelhouse and Bangladeshi Bishop Gomes. The conference, co-organised with Caritas Poland and the Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, gathered faith-actors, civil society actors, politicians and climate scientists to work together towards climate justice on the occasion of the COP19 climate negotiations. The Holy See representative to Poland, Head of the Holy See Delegation to the COP19, Nuncio and Archbishop Celestino Migliore, opened the conference with an inspired plea. “Climate change is an ethical challenge for our civilization, asking us what changes we need to affect in our economic life, in the structures of our society and in the way we consume.” Recent polls conducted in Poland (by Public Opinion Research Center CBOS) show 89 % support for expanding renewable energy, with minority support for coal and lignite. A coal summit with backing from the Polish government in parallel to the COP19 negotiations and at the same time as the CIDSE conference, where Church representatives present spoke strongly of their concern for the poor and vulnerable in the world suffering most from climate change and called on governments to reduce radically exploitation of coal, oil and other fossil resources. Mr Andrzej Kassenberg of the Institute for Sustainable Development presented a study of the costs of “business as usual” for Poland and highlighted how the economy and to employment would benefit from shifting to renewable energy. -

Face up to Anti-Catholicism

No 5495 YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLICwww.sconews.co.uk NEWSPAPER SUPPORTS THE YEAR OF FAITH Friday November 30 2012 | £1 SCIAF FUNDING BOOST CELEBRATING ST ANDREW’S DAY WITH A SMILE OR TWO MALAWI PROJECTS run by the charity receive nearly £500,000 from the Scottish Government Page 7 Archbishop Philip Tartaglia of Glasgow joined staff and pupils of the city’s St Andrew’s Secondary School on Monday to celebrate a feast day Mass for the school’s patron saint. In anticipation of the feast day, today, Gerry Lyons, St Andrew’s headteacher, and the school community were delighted to welcome Archbishop Tartaglia and priests of the archdiocese —including Fr Joseph Sullivan, school chaplain and a former pupil at the school, and Fr Mark Morris, also a former pupil—for the celebrations. The archbishop, making his first visit to a Glasgow secondary school since his inauguration in September, blessed St Andrew’s new oratory and also launched the school’s charities’ campaign PIC: PAUL McSHERRY Face up to anti-Catholicism ST ANDREW’S CONFERENCE IArchbishop Tartaglia says the Scottish Government must endeavour to tackle the problem By Ian Dunn Catholic community of Scotland “I think the vast majority of clergy remains steadfast in faith, joyful in and laity in this country have developed ARCHBISHOP Philip Tartaglia of hope and fully committed to being part very thick skins,” he said. “The vast Glasgow has said that the Scottish of Scottish society.” majority of crimes against Catholics are Government is refusing to face up never reported.” to the brutal nature of anti-Catholi- Failing Catholics cism in Scotland, as new Crown Peter Kearney, director of the Scottish Problem worsening Office statistics show an increase in Catholic Media Office, said the rise in Dave Scott of the charity Nil by Mouth attacks on Catholics. -

Journeying Toward Care for Our Common Home

INTERDICASTERIAL WORKING GROUP The Interdicasterial Working Group The world has been shaken by the crisis created by OF THE HOLY SEE ON INTEGRAL ECOLOGY “The urgent challenge to protect of the Holy See on Integral Ecolo- the Covid-19 pandemic, which has led to the death of our common home includes a gy was established in 2015 for the many thousands of people and is changing our way of concern to bring the whole hu- study, promotion and implemen- life. At this difficult time, which will certainly bring man family together to seek a tation of integral ecology in the sustainable and integral develop- changes to the societies in which we live, we are called light of Laudato Si’. It brings to- HOME ment, for we know that things can gether institutions associated with to care for one another and to avoid becoming closed change… It is my hope that this the Holy See, Episcopal Confer- in on ourselves. The crisis we are experiencing makes Encyclical Letter … can help us to ences and Catholic organizations ever more evident – five years after its publication – acknowledge the appeal, immen- involved in this area. the importance of the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ sity and urgency of the challenge that Pope Francis wrote on care for our common home, we face”. COMMON which teaches that everything is connected within the POPE FRANCIS, Laudato Si’ lens of integral ecology. Seriously facing the causes (n. 13, 15), 24 May 2015 OUR of this crisis will require a real change of direction and JOURNEYING a spiritual conversion which can lead to a renewed FOR awareness of our relation with ourselves, with others, TOWARDS CARE FOR with society, with creation and with God. -

Caritas-CIDSE G20 Network

1 Caritas‐CIDSE G20 Network Food Security and the G20 “Hunger is not so much dependent on lack of material things, as on shortage of social resources, the most important of which are institutional.” Pope Benedict XVI (Caritas in Veritate) 2 It is the right of all human beings to live in dignity, free from hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition. There are nearly a billion people suffering from hunger in the world today3. In every society food does not comprise of solely material ‘nutritional’ elements, but also social, economic, political, cultural elements connected to food use, production and trade. Food issues are therefore of utmost importance because they are linked to a much wider set of livelihood issues. Endangering food security has obvious impacts on the most vulnerable social groups, the poorest. Improving food security is not an objective that can be pursued with a purely ‘quantitative’ approach (more food=more food security), but within a wider ‘right to food’ approach. His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI, in his address to FAO at the World Summit on Food Security, declared; hunger is “the most cruel and concrete sign of poverty”, assuming such proportions as to make opulence and waste unacceptable4. He highlighted that food insecurity stems not from the lack of sufficient food, but rather from the increasing disparity in levels of development between and within countries. The steady contrast between poverty and wealth may dangerously lead one to consider food insecurity as a structural reality typical of poorer countries. As a network of Catholic social and development agencies, we will never subscribe to this view.