O'hara, Suzy and Bradbury, Victoria (2019) Art Hack Practice: Critical Intersections of Art, Innovation and the Maker Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn to Lead Activity Guide

LEARN TO LEAD ACTIVITY GUIDE CIVIL AIR PATROL CADET PROGRAMS TEAM LEADERSHIP PROBLEMS MOVIE LEARNING GUIDES GROUP DISCUSSION GUIDES Preface LEARN TO LEAD ACTIVITY GUIDE Do you learn best by reading? By listening to a lecture? By watching someone at work? If you’re like most people, you prefer to learn by doing. That is the idea behind the Learn to Lead Activity Guide. Inside this guide, you will find: • Hands-on, experiential learning opportunities • Case studies, games, movies, and puzzles that test cadets’ ability to solve problems and communicate in a team environment • Recipe-like lesson plans that identify the objective of each activity, explain how to execute the activity, and outline the main teaching points • Lesson plans are easy to understand yet detailed enough for a cadet officer or NCO to lead, under senior member guidance The Activity Guide includes the following: • 24 team leadership problems — Geared to cadets in Phase I of the Cadet Program, each team leadership problem lesson plan is activity- focused and addresses one of the following themes: icebreakers, teamwork fundamentals, problem solving, communication skills, conflict resolution, or leadership styles. Each lesson plan includes step-by-step instructions on how to lead the activity, plus discussion questions for a debriefing phase in which cadets summarize the lessons learned. • 6 movie learning guides — Through an arrangement with TeachWithMovies.com, the Guide includes six movie learning guides that relate to one or more leadership traits of Learn to Lead: character, core values, communication skills, or problem solving. Each guide includes discussion questions for a debriefing phase in which cadets summarize the lessons learned. -

To Give You a Flavour of the Venue, Click Here To

CONTENTS 4 WELCOME Professor Sir Robert Burgess 6 FOREWORD Almuth Tebbenhoff FRBS 9 EssaY Tom Flynn previous page William Tucker Cybele Bronze 1994 47 BIOGRAPHIES Courtesy Yorkshire Sculpture Park 50 GLOSSARY right Brigitte Jurack Glizzit 50 CREDITS Dutch gold leaf, plastic 2012 overleaf page 5 Mary Bourne Regeneration Black granite 1996 WELCOME FROM THE Vice-CHANCELLOR Professor Sir Robert Burgess I AM DELIGHTED to welcome you to the winning many awards. We have been inspired Garden changes colour and plants continue eleventh Annual Sculpture in the Garden and delighted with her choice of sculptures to grow, your perception of the sculptures exhibition at the University of Leicester. and artists. will also change. Since 2002 we have organised and hosted this exhibition in the beautiful surroundings Taking a radical new approach to the Finally I am very grateful to be able to of the Harold Martin Botanic Garden and exhibition, Almuth has directly approached call upon the expertise of experienced it has proved to be increasingly popular each artists who she believes reflect her chosen sculptors to curate the exhibition and am year. The Garden has been owned by the theme “Interesting Times” – a reference to an very appreciative of the links that have University since 1947, spans a total area Ancient Chinese proverb. Working across a been developed with artists’ studios, the of sixteen acres and is home to many diverse range of techniques these artists have Royal British Society of Sculptors, the Cass significant plant collections. It has always been responded in very different ways and we hope Sculpture Foundation, Pangolin’s Gallery, a great asset to the University and continues this approach will stimulate debate and raise the Yorkshire Sculpture Park and all the to provide researchers, young people and awareness of the complex and ever-changing individual artists and staff who have made members of the general public with world in which we live. -

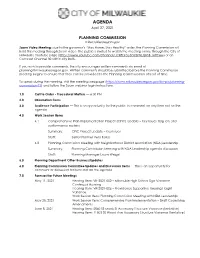

Planning Comission Packet 04.27.2021

AGENDA April 27, 2021 PLANNING COMMISSION milwaukieoregon.gov Zoom Video Meeting: due to the governor’s “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order, the Planning Commission will hold this meeting through Zoom video. The public is invited to watch the meeting online through the City of Milwaukie YouTube page (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRFbfqe3OnDWLQKSB_m9cAw) or on Comcast Channel 30 within city limits. If you wish to provide comments, the city encourages written comments via email at [email protected]. Written comments should be submitted before the Planning Commission meeting begins to ensure that they can be provided to the Planning Commissioners ahead of time. To speak during the meeting, visit the meeting webpage (https://www.milwaukieoregon.gov/bc-pc/planning- commission-71) and follow the Zoom webinar login instructions. 1.0 Call to Order - Procedural Matters — 6:30 PM 2.0 Information Items 3.0 Audience Participation — This is an opportunity for the public to comment on any item not on the agenda 4.0 Work Session Items 4.1 Comprehensive Plan Implementation Project (CPIC) Update – Key Issues: flag lots and performance metrics Summary: CPIC Project Update – Key Issues Staff: Senior Planner Vera Kolias 4.2 Planning Commission Meeting with Neighborhood District Association (NDA)Leadership Summary: Planning Commission Meeting with NDA Leadership agenda discussion Staff: Planning Manager Laura Weigel 5.0 Planning Department Other Business/Updates 6.0 Planning Commission Committee Updates and Discussion Items — This is an opportunity -

Strategic Plan 2016 – 2021

Strategic Plan 2016 – 2021 1 Ability to Meet the Mission Acknowledging the accomplishments and agility of Academy of Art University since its founding in 1929, the Strategic Plan envisions where we will take art and design education in the next five years. The Plan articulates the steps we must take to ensure the very best experience for our students, who are at the heart of the institution in the short, medium and long term. Origins President Stephens launched the Strategic Planning Initiative in spring 2015. Throughout the academic year, input was solicited from constituent groups across campus. » Academic Department Directors » Faculty » Board of Directors » Senior Management Team » Students The recommendations in Academy of Art University’s Strategic Plan 2016 – 2021 represent the culmination of feedback from these constituencies. The Strategic Plan was crafted in late fall 2015 by the Strategic Planning Task Force, led by President Elisa Stephens and Chairman of the Board of Directors Dr. Nancy Houston. Key Academy of Art University leaders in the areas of education, finance, operations and technology participated on the Task Force. Implementation and Review The Strategic Plan will be shared with the constituent groups at Academy of Art University that created it, and with the WASC Senior College & University Commission (WSCUC) and Academy of Art University’s other institutional and programmatic accreditors. Individual strategic goals will be assigned to managers and existing or ad hoc work teams, as appropriate to best execute individual strategic goals. Progress on implementing the plan will be reviewed quarterly as part of the President’s Report to the Board of Directors and also as part of Senior Management Team Meetings and Academic Department Director Meetings. -

Kahlil Gibran a Tear and a Smile (1950)

“perplexity is the beginning of knowledge…” Kahlil Gibran A Tear and A Smile (1950) STYLIN’! SAMBA JOY VERSUS STRUCTURAL PRECISION THE SOCCER CASE STUDIES OF BRAZIL AND GERMANY Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan P. Milby, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Melvin Adelman, Adviser Professor William J. Morgan Professor Sarah Fields _______________________________ Adviser College of Education Graduate Program Copyright by Susan P. Milby 2006 ABSTRACT Soccer playing style has not been addressed in detail in the academic literature, as playing style has often been dismissed as the aesthetic element of the game. Brief mention of playing style is considered when discussing national identity and gender. Through a literature research methodology and detailed study of game situations, this dissertation addresses a definitive definition of playing style and details the cultural elements that influence it. A case study analysis of German and Brazilian soccer exemplifies how cultural elements shape, influence, and intersect with playing style. Eight signature elements of playing style are determined: tactics, technique, body image, concept of soccer, values, tradition, ecological and a miscellaneous category. Each of these elements is then extrapolated for Germany and Brazil, setting up a comparative binary. Literature analysis further reinforces this contrasting comparison. Both history of the country and the sport history of the country are necessary determinants when considering style, as style must be historically situated when being discussed in order to avoid stereotypification. Historic time lines of significant German and Brazilian style changes are determined and interpretated. -

Unleashing Young People's Creativity and Innovation

Unleashing young people’s creativity and innovation European good practice projects Picture on the cover page: ©2015 Shape Arts. All rights reserved. Photography by Laura Braun, ‘Articulate UK’ conference, 2010 at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London. The images in this publication provide a general illustration of some of the projects funded by the Youth in Action/Erasmus+ programme. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2015 ISBN: 978-92-79-40162-6 doi: 10.2766/8245 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Unleashing young people’s creativity and innovation European good practice projects Martine Reicherts Director-General for Education and Culture European Commission Foreword This brochure contains inspiring initiatives, practices and tools, including the EU projects, that showcase how youth work and non-formal learning can enhance young people’s creativity and innovation, through their experimental nature, participatory approaches, and peer-learning, and how this can help them to find their place in the labour market - and in life. It is the result of peer learning in an expert group which was looking into constructive response to challenges faced by many young people in Europe. At present, 13,7 million 15-29 year-olds are not in employment, education or training. And many of those who gain employment find that the reality of the job falls well below their ambitions and vision. Reliable pathways through education and training to quality employment are often lacking. -

Middle School Art Lessons That Embrace the Value of Compassion

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design Summer 8-12-2014 A Catalyst Toward Caring: Middle School Art Lessons that Embrace the Value of Compassion Lauren Ashley Stovall Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Stovall, Lauren Ashley, "A Catalyst Toward Caring: Middle School Art Lessons that Embrace the Value of Compassion." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/164 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CATALYST TOWARD CARING: MIDDLE SCHOOL ART LESSONS THAT EMBRACE THE VALUE OF COMPASSION by LAUREN STOVALL Under the Direction of Dr. Melody Milbrandt ABSTRACT This study discusses the importance of theories of care that are especially relevant to students in middle school art classes. Middle school students are going through an increasing number of changes emotionally, mentally, and cognitively that can be explored through an art curriculum that teaches them the value of caring for themselves and others, while also meeting their developmental needs. In this thesis research, teaching strategies are discussed that will cultivate an environment of care in the middle school classroom. This information will be used in the construction of developmentally sequenced art lessons that put these caring attitudes, strategies, and practices into action through art studio and criticism lessons incorporating the national art education standards. -

2014 Boring Fire

Boring Fire District and Clackamas Fire District #1, OR Opportunities for Collaborative Efforts Feasibility Study Prepared By: Don Bivins, Project Manager Jim Broman, Associate Jim Mooney, Associate Ron Oliver, Associate Rob Strong, Associate Nola von Neudegg, Associate Boring Fire District and Clackamas Fire District #1, Oregon Opportunities for Collaborative Efforts Feasibility Study Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Approach ........................................................................................................... 1 Key Findings .......................................................................................................................... 3 Recommendations ................................................................................................................. 5 Next Steps .............................................................................................................................. 6 Evaluation of Current Conditions ................................................................................................. 7 Organization Overview ............................................................................................................. 7 Management Components ..................................................................................................... -

A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India Preston G

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Capstone Collection SIT Graduate Institute Winter 12-4-2017 Lessons for Legalizing Love: A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India Preston G. Johnson SIT Graduate Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, History of Gender Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Litigation Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Political Science Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, Social Policy Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Preston G., "Lessons for Legalizing Love: A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India" (2017). Capstone Collection. 3063. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones/3063 This Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Graduate Institute at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Hans Arp & Other Masters of 20Th Century Sculpture

Hans Arp & Other Masters Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers of 20th Century Sculpture Volume 3 Edited by Elisa Tamaschke, Jana Teuscher, and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 3 Hans Arp & Other Masters of 20th Century Sculpture Edited by Elisa Tamaschke, Jana Teuscher, and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Hans Arp & Other Masters of 20th Century Sculpture An Introduction Jana Teuscher 20 Negative Space in the Art of Hans Arp Daria Mille 26 Similar, Although Obviously Dissimilar Paul Richer and Hans Arp Evoke Prehistory as the Present Werner Schnell 54 Formlinge Carola Giedion-Welcker, Hans Arp, and the Prehistory of Modern Sculpture Megan R. Luke 68 Appealing to the Recipient’s Tactile and Sensorimotor Experience Somaesthetic Redefinitions of the Pedestal in Arp, Brâncuşi, and Giacometti Marta Smolińska 89 Arp and the Italian Sculptors His Artistic Dialogue with Alberto Viani as a Case Study Emanuele Greco 108 An Old Modernist Hans Arp’s Impact on French Sculpture after the Second World War Jana Teuscher 123 Hans Arp and the Sculpture of the 1940s and 1950s Julia Wallner 142 Sculpture and/or Object Hans Arp between Minimal and Pop Christian Spies 160 Contributors 164 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp is one of the established greats of twentieth-century art. As a founder of the Dada movement and an associate of the Surrealists and Con- structivists alike, as well as co-author of the iconic book Die Kunst-ismen, which he published together with El Lissitzky in 1925, Arp was active at the very core of the avant-garde. -

Media, Politics and the Network Society

Media and politics… 11/3/04 3:11 pm Page 1 I S SUE S in CULTURAL and MEDIA STUDIES I S SUE S in CULTURAL and MEDIA STUDIES SERIES EDITOR: STUART ALLAN Hassan Robert Hassan Media, Politics and the Network Society • What is the network society? • What effects does it have upon media, culture and politics? • What are the competing forces in the network society, and how are they reshaping the world? The rise of the network society – the suffusion of much of the economy, culture and society with digital interconnectivity – is a development of immense significance. In this innovative book, Robert Hassan unpacks the dynamics of this new information order and shows how they have affected both the way media and politics are ‘played’, and how these are set to reshape and reorder our world. Using many of the current ideas in media theory, cultural studies and the politics of the newly evolving ‘networked civil society’, Hassan argues that the network society is steeped with contradictions and in a state of deep flux. Media, Politics Media, Politics This is a key text for undergraduate students in media studies, politics, cultural studies and sociology, and will be of interest to anyone who wishes to understand the network society and play a part in shaping it. Robert Hassan is Australian Research Council Fellow in Media and Media, Communications at the Institute for Social Research, Swinburne University, Australia. He has written numerous articles on the nature of the network society from the and the perspectives of temporality, political economy and media theory, and is author of The Chronoscopic Society (2003). -

Ao No Exorcist Mp3 Download

Ao no exorcist mp3 download click here to download Album name: Ao no Exorcist OP Single - CORE PRIDE Number of New! Download all songs at once: Download to Computer (FLAC+MP3). Free Anime Downloads. Ao no Exorcist OP2 Single - IN MY WORLD Download all songs at once: Download to Computer (FLAC+MP3). Album name: Ao no Exorcist ED Single - Take off. Number of Files: 6. Total Filesize: MB Date added: Apr 25th, New! Download all songs at once. Album name: Ao no Exorcist Original Soundtrack 1. Number of Files: Total Filesize: MB Date added: Apr 25th, New! Download all songs at. Album name: Ao no Exorcist ED2 Single - Wired Life Number of Files: 4. Total Filesize: MB Date added: Apr 25th, New! Download all songs at once. Tag: Download Mp3, Soundtrack Anime Mp3, Download OST Anime Full Version, OST Ao no Exorcist (OP) Kbps, Download OST Anime, Download Lagu. Free download in My World Ao No Exorcist – The Blue Exorcist Mp3. We have about 31 mp3 files ready to play and download. To start this. Convert Youtube Ao no Exorcist Season 2 Full opening『UVERworld - Itteki no Eikyou』 to MP3 instantly. Yo Minna, selamat tahun baru ya.. Nah, di awal tahun ini mimin ingin berbagi lagu Ost opening dan ending Anime terbaru yaitu Ao no. Download Ost Ao no Exorcist | OP 1 CORE PRIDE by UVERWorld | OP 2 IN MY WORLD by ROOKiEZ is PUNK'D | ED 1 Take off by 2PM | ED. Download Ost Opening and Ending Anime Ao no Exorcist, "CORE PRIDE" by UVERWorld, "IN MY WORLD" by ROOKiEZ is PUNK'D, "Take off".