UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring-2018-Manuscript-2.Pdf

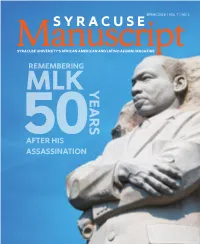

SPRING 2018 | VOL. 7 | NO. 1 SYRACUSE ManuscriptSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY’S AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINO ALUMNI MAGAZINE REMEMBERING MLK YEARS 50AFTER HIS ASSASSINATION CONTENTS Brandyn Munford ’18 and Anjana Pati ’18 presented Angela Rye with a ceramic platter created by Professor Emeritus David MacDonald at SU’s 2018 MLK Celebration. CONTENTS Contents From the ’Cuse ..........................................................................2 Remembering MLK ................................................................3 Stith Leads Norfolk State ....................................................6 Fuller Creates Endowment .................................................7 Vincent H. Cohen Sr. Honored with Named Scholarship ................................................................8 Paris Noir Endowment ..........................................................9 Student Spotlight ............................................................10 OTHC Scholarship Donor List .....................................12 6 Campus News ..................................................................14 3 Alumni News .....................................................................18 CBT Martha’s Vineyard..................................................26 Alumni Milestones ................................................................ 26 In Memoriam .......................................................................... 27 19 7 22 8 15 16 18 10 11 ON THE COVER: Martin Luther Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. RACHEL VASSEL ’91, Assistant -

Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little

The Ensley Athletic Center is the latest major facilities addition to the Lampe Athletics Complex. The $13 million building was constructed in seven months and opened in January 2015. It serves as an indoor training center for the football program, as well as other sports. A multi- million dollar gift from Cliff Ensley, a walk-on who earned a football scholarship and became a three-sport standout at Syracuse in the late 1960s, combined with major gifts from Dick and Jean Thompson, made the construction of the 87,000 square-foot practice facility possible. The construction of Plaza 44, which will The Ensley Athletic Center includes a 7,600 tell the story of Syracuse’s most famous square-foot entry pavilion that houses number, has begun. A gathering area meeting space and restrooms. outside the Ensley Athletic Center made possible by the generosity of Jeff and Jennifer Rubin, Plaza 44 will feature bronze statues of the three men who defi ne the Legend of 44 — Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little. Syracuse defeated Minnesota in the 2013 Texas Bowl for its third consecutive bowl victory and fi fth in its last six postseason trips. Overall, the Orange has earned invitations to every bowl game that is part of the College Football Playoff and holds a 15-9-1 bowl record. Bowl Game (Date) Result Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1953) Alabama 61, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1957) TCU 28, Syracuse 27 Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1959) Oklahoma 21, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1960) Syracuse 23, Texas 14 Liberty Bowl (Dec. -

2010 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL FINAL RELEASE: 8-5 Overall, 4-3 BIG EAST

2010 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL FINAL RELEASE: 8-5 overall, 4-3 BIG EAST Orange Invited to Inaugural Pinstripe Bowl ORANGE SLICES Syracuse University, New York’s College Team, is making history in the Big Apple once again. The Orange will represent The BIG EAST Conference in the first New Era Pinstripe Bowl, playing against Kansas State on Orange on Television Thursday, Dec. 30 at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx (3:30 p.m., ESPN). The New Era Pinstripe Bowl will be televised on ESPN … Bob Wischusen and Brian Griese will call • The Orange earned its first bowl bid since 2004 on the strength of a 7-5 record in Marrone’s second the action from the booth with Eamon McAnaney season. Marrone, a life-long fan of the New York Yankees, is a Bronx native and a 1982 graduate of reporting from the sidelines … Bryan Ryder will Herbert H. Lehman High School, located less than 10 minutes from Yankee Stadium. produce the broadcast. • Marrone’s affinity for the Yankees isn’t his only tie to the 27-time World Series champions. His maternal grandfather, Robert Thompson, worked as an usher at old Yankee Stadium for nearly 20 years. Orange on Radio • Syracuse has a rich football history in New York City and the metropolitan area. The Orange is 5-1 all- Syracuse Sports Network time at Yankee Stadium, including a 3-0 victory against Pittsburgh in 1923 in the first college football Voice of the Orange Matt Park ‘97 and former game ever played there. In addition, the Orange has played seven times at the Polo Grounds in New Orange All-American tight end Chris Gedney York City and taken the field for games at Shea Stadium in Flushing, N.Y. -

Download Download

Journal of Intercollegiate Sport, 2021, 14.1, 115-141 https://doi.org/10.17161/jis.v14i1.13367 © 2021 the Authors The Circle of Unity: The power of symbols in a team sport context Brendan O’Hallarn1, Craig A. Morehead2, Mark A. Slavich3, and Alicia M. Cintron4 1Old Dominion University, 2Indiana State University, 3Grand View University, 4University of Cincinnati Modern-day political discord has led to a recent spate of athletes using their platform to make statements about America. One under-researched aspect to modern sport activism is the study of the symbols themselves, such as the controversial kneeling during the national anthem by National Football League players, statement-making pregame apparel worn by National Basketball Association stars, and other political statements. This case study examines a 2016 activist display by Old Dominion Uni- versity’s football team, known as the Circle of Unity. The display, performed before most games that season, began as a form of protest by team captains, and morphed into a gesture that was celebrated across the political spectrum. Through the lens of both Symbolic Interactionism (SI) and Critical Race Theory (CRT), the current study seeks to uncover the impetus, meaning, and ultimate impact of the symbol on a variety of stakeholders. Examining the symbol used—players and coaches stand- ing in a circle, facing out, holding hands and raising them to the sky—can further contextualize the challenging role that student-athletes have in finding their voice to speak on issues they care about in a divided America. Keywords: athlete activism, politics in sport, symbolic interactionism, college foot- ball, Old Dominion University Fans arriving for the kickoff of Old Dominion University’s (ODU) football game against the University of Texas-San Antonio (UTSA) on September 24, 2016 were greeted with a curious sight. -

Sandra Day O'connor College of Law Arizona State University

ARIZONA STATE SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 7 SPRING 2018 ISSUE 2 SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR COLLEGE OF LAW ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY 111 EAST TAYLOR STREET PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85004 ABOUT THE JOURNAL The Arizona State Sports and Entertainment Law Journal is edited by law students of the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University. As one of the leading sports and entertainment law journals in the United States, the Journal infuses legal scholarship and practice with new ideas to address today’s most complex sports and entertainment legal challenges. The Journal is dedicated to providing the academic community, the sports and entertainment industries, and the legal profession with scholarly analysis, research, and debate concerning the developing fields of sports and entertainment law. The Journal also seeks to strengthen the legal writing skills and expertise of its members. The Journal is supported by the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and the Sports Law and Business Program at Arizona State University. WEBSITE: www.asuselj.org. SUBSCRIPTIONS: To order print copies of the current issue or previous issues, please visit Amazon.com or visit the Journal’s website. SUBMISSIONS: Please visit the Journal’s website for submissions guidance. SPONSORSHIP: Individuals and organizations interested in sponsoring the Arizona State Sports and Entertainment Law Journal should contact the current Editor-in-Chief at the Journal’s website. COPYRIGHT ©: 2017–2018 by Arizona State Sports and Entertainment Law Journal. All rights -

Student Movements Against the Imperial University: Toward a Genealogy of Disability Justice in U.S. Higher Education

Available online at http://eScholarship.org/uc/ucbgse_bre Student Movements Against the Imperial University: Toward a Genealogy of Disability Justice in U.S. Higher Education Laura J. Jaffee1 Department of Educational Studies, Colgate University Ahmed (2017) reminds us that “it is through the effort to transform institutions that we generate knowledge about them” (p. 93). Although academic disciplines may work, as the name suggests, to discipline us—separating necessarily connected work, areas of knowledge, and people—university professors are not the sole producers of knowledge within universities. University students, staff and faculty workers, and broader community members generate knowledge through collective work aimed at institutional transformation. Heeding Ahmed’s words, this article explores knowledge produced by student activists working toward social transformation through social movement spaces on college campuses. I emphasize knowledge that contests and refuses the university and its collusion with imperialism, settler- colonialism, and white, able-bodied supremacy. I focus on collective student action to resist a sense of cynicism or despondence that is all too easy to slip into (i.e., both for students committed to fighting oppression, and for workers situated within academe) when we recognize that universities are not the “engines of social transformation” that dominant ideology would have us believe (Kelley, 2016, para. 14). Building off scholarship that analyzes higher education’s institutional support for the mutually-imbricated forces of settler-colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, and white and able-bodied supremacy, this article takes as its focus the insurgent spaces—those non-sanctioned learning spaces where knowledge with transformative power is produced—created by student-organizers collectively challenging institutional complicity with these systems (Ahmed, 2012; Boggs & Mitchell, 2018; Grande, 2018; Howell, 2018; Stein, 2018). -

![Summer 2019 Magazine [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7655/summer-2019-magazine-pdf-6717655.webp)

Summer 2019 Magazine [PDF]

Syracuse University’s African American and Latino Alumni Magazine Summer 2019 | Vol. 8 | No. 1 ManuscriptSyracuse CONGRATS TO THE CLASS OF 2019! Thank you, donors, for helping launch their futures. Nerys Castillo-Santana ’19 | SYRACUSE MANUSCRIPT Syracuse Manuscript INSIDE THIS ISSUE Rachel Vassel ’91 Contents Assistant Vice President Mulitcultural Advancement From the ’Cuse 2 Adrian Prieto Director of Development OTHC Holds Reception on Mulitcultural Advancement Avenue of the Stars 3 Miko Horn ’95 Introducing the Office of Multicultural Director, Alumni Events Advancement 4 Mulitcultural Advancement 6 Angela Morales-Patterson Student Spotlight 6 Assistant Director, Alumni and Donor Engagement Mulitcultural Advancement Our Time Has Come Scholarship Donor List 12 Campus News 16 Angela Morales-Patterson Editor-in-Chief Alumni News 24 Renée Gearhart-Levy Writer 16 Donor Highlight 28 George Bain Editorial Assistance Alumni Events 29 Quinn Page Design LLC Design In Memoriam 31 Jennifer Merante Project Manager Office of Mulitcultural Advancement 24 Syracuse University 640 Skytop Rd, Second Floor Syracuse NY 13244-5160 On the Cover (From left): Abigail Covington ’19, 315.443.4556 Stacy Fernández ’19, Marcus Lane Jr. ’19, and Maia Wilson ’19 f 315.443.2874 syracuse.edu/alumniofcolor [email protected] Opinions expressed in Syracuse Manuscript are those 28 of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of its editors or the policies of Syracuse University. © 2019 Syracuse University Office of Multicultural Advancement. All rights reserved. 29 Photo by Ross Oscar Knight SUMMER 2019 | 1 FROM THE ’CUSE THE JOY OF GIVING Like many of you, I was thrilled to learn of billionaire Robert Smith’s gift to this year’s graduating class at Morehouse College in Atlanta. -

![Fall 2018 Magazine [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2996/fall-2018-magazine-pdf-6762996.webp)

Fall 2018 Magazine [PDF]

Syracuse University’s African American and Latino Alumni Magazine Fall 2018 | Vol. 7 | No. 2 ManuscriptSyracuse OTHC Scholars Nordia Mullings, Nerys Castillo-Santana and Amber Hunter Syracuse Manuscript INSIDE THIS ISSUE Rachel Vassel ’91 Contents Assistant Vice President, Program Development Arianne Dowdell G’96 From the ’Cuse 2 Senior Director, Operations and Partnerships Alumni Enjoy Martha’s Vineyard 3 Adrian Prieto Director of Development, Program Development OTHC Mentorship Program 4 Miko Horn ’95 Director, Alumni Events 6 OTHC Leadership Program 5 Angela Morales-Patterson Assistant Director, Alumni and Donor Engagement Student Spotlight 6 Susan C. Blanca Administrative Specialist, Program Development Our Time Has Come Scholarship Donor List 10 Campus News 14 Angela Morales-Patterson Editor-in-Chief Alumni News 20 Renée Gearhart-Levy Writer 16 Alumni Milestones 26 George Bain Editorial Assistance In Memoriam 27 Quinn Page Design LLC CBT Wins Gold Case Award 29 Design Melanie Stopyra Project Manager Office of Program Development 18 Syracuse Univerity On the Cover 640 Skytop Rd, Second Floor Syracuse NY 13244-5160 315.443.4556 f 315.443.2874 programdevelopment.syr.edu [email protected] Opinions expressed in Syracuse Mancuscript are those 26 of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of its editors or the policies of Syacuse University. © 2018 Syracuse University Office of Program Our Alumni Bleed Orange! Development. All rights reserved. 29 FALL 2 0 1 8 | 1 FROM THE ’CUSE SOMETHING NEW! It’s difficult to start something new. Often, we tend to hold on to what is familiar, comfortable, and safe. Back in the day, we used to say that someone is “feeling brand new” when that person was being bold, sassy, happy with, or proud of themselves. -

V4 Spring 2018 Issue 2

MORE THAN AN ATHLETE: CONSTITUTIONAL AND CONTRACTUAL ANALYSIS OF ACTIVISM IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTS SARAH BROWN* & NATASHA BRISON** INTRODUCTION Athlete activism is not a new issue. Rather, athletes at all levels and sports have used their platforms to protest long before Colin Kaepernick took a knee. During the 1960s and 1970s, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, athletes including Muhammad Ali, Bill Russell, Jim Brown, and Arthur Ashe advocated for civil rights.1 As the fight for civil rights settled, so did athlete activism.2 In the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, prominent athletes shied away from social movements most likely due to the fear of financial repercussions, such as losing endorsements. 3 Even LeBron James, 14 time National Basketball Association (NBA) All-Star, commented in 2008 that “sports and politics just don’t match.”4 Recently social justice and civil rights issues are back at the forefront of national discussion, and athlete activism has increased.5 While the number of athletes who engage in activism * Sarah M. Brown is a doctoral student in the Sport Management Division at Texas A&M University. She received her J.D. from Marquette University Law School, where she served as the Survey Editor for the Marquette Sports Law Review. ** Natasha T. Brison is an Assistant Professor in the Sport Management Division at Texas A&M University. She received both her Ph.D. in Sport Management & Policy and her J.D. from the University of Georgia. 1 Danielle Sarver Coombs & David Cassilo, Athletes and/or Activists: LeBron James and Black Lives Matter, 41 J. -

Greg Allen Podcast Transcript

This transcript was exported on Nov 05, 2020 - view latest version here. John Boccacino: Hello, and welcome back to the Cuse Conversations Podcast. My name John Boccacino, the communication specialist in Syracuse University's Office of Alumni Engagement. I'm also a 2003 graduate of the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, with a degree in broadcast journalism. I am so glad you found our podcast. Well folks, today on the Cuse Conversations Alumni Podcast, I am pleased to welcome on Greg Allen, a former Syracuse football player, a proud [inaudible 00:00:38] of Syracuse University. He has a terrific story to tell you as one of the members of the Syracuse 8. And, for those who don't know, we're going to get into the details of the Syracuse 8, the racial issues that were taking place on Syracuse University's campus, in the late 60s and early 70s, and the role that Greg and a lot of his teammates took, in fighting for racial equality. These topics are extremely timely, given everything we're dealing with here in 2020 with George Floyd, with Jacob Blake, with all of these social justice movements, that are taking place across the country. John Boccacino: And Greg, I know that's kind of a overarching way to get into our conversation, but first of all, I want to welcome you to the podcast. And, I hope that you're doing well during these tumultuous times. Greg Allen: Yes I am. I'm doing well, me and the family are doing well.