Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlotte 49Ers Athletics

CHARLOTTE 49ERS ATHLETICS ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR........................................................ 1 MEN’S BASKETBALL................................................................................................2 WOMEN’S BASKETBALL......................................................................................... 3 MEN’S SOCCER........................................................................................................4 WOMEN’S SOCCER.................................................................................................5 GOLF............................................................................................................................ 6 VOLLEYBALL............................................................................................................... 7 BASEBALL...................................................................................................................8 SOFTBALL ................................................................................................................... 9 TRACK & FIELD...................................................................................................10-11 MEN'S TENNIS.........................................................................................................12 WOMEN’S TENNIS..................................................................................................13 FOOTBALL.......................................................................................................14 -

Fun Things to Do

Y-GUIDES FUN THINGS TO DO Charlotte Knights - Men’s Minor League Baseball Team ATHLETIC EVENTS Enjoy a night out with the Knights! The Charlotte Knights are a minor league baseball team. The team plays in the Charlotte Hornets - Men’s Basketball International League and is the Triple-A affiliate of the Enjoy a night out as a tribe at the Hornets game! The Chicago White Sox of the American League. The Knights Charlotte Hornets play in the Southeast Division of the play in the BB&T Ballpark in Uptown Charlotte, one block Eastern Conference in the National Basketball Association. from the Bank of America Stadium, home of the Carolina The Hornets, established in 1988, moved to New Orleans in Panthers. 2002. The Bobcats were formed in 2004 as an expansion team. The Hornets name returned in the 2014-2015 Call Yogi Brewington at 704 274 8215 for group rate season. The team is owned by former NBA player Michael information. Jordan, who acquired the team in 2010. The Hornets play their home games at Spectrum Center in uptown Charlotte. YMCA of Greater Charlotte A YMCA membership gives you so much more than just a place to work out! As a YMCA member, you have full use For information regarding Hornets of our 19 locations in Mecklenburg, Union, Lincoln, Iredell information and Spectrum Counties, including access to all of our outdoor pools and Arena concerts and shows please waterparks in addition to the lakefront at the Lake Norman contact Steven Tacchi at YMCA. Plus much more! 704 688 9072 or [email protected] Check out www.ymcacharlotte.org Charlotte Checkers - Men’s AHL Hockey Team PERFORMANCES Join the Charlotte Checkers for an action packed game on the ice! The Charlotte Checkers are a minor-league Children’s Theatre of Charlotte professional ice hockey team. -

Defining and Addressing the Intersection of Sports, Media, and Social Activism

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 3-26-2021 Defining and Addressing the Intersection of Sports, Media, and Social Activism Kaylee Layne Crafton Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, Public Relations and Advertising Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Crafton, Kaylee Layne, "Defining and Addressing the Intersection of Sports, Media, and Social Activism" (2021). Honors Theses. 1745. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1745 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEFINING AND ADDRESSING THE INTERSECTION OF SPORTS, MEDIA, AND SOCIAL ACTIVISM by Kaylee Layne Crafton A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, MS March 2021 Approved By ______________________________ Advisor: Professor Deborah Hall ______________________________ Reader: Professor Will Norton ______________________________ Reader: Iveta Imre © 2021 Kaylee Layne Crafton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION “Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for human masters, since you know that you will receive an inheritance from the Lord as a reward. It is the Lord Christ you are serving.” Colossians 3:23-24 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I simply do not have the adequate words to express my gratitude for the support that I have received from so many people throughout this project. -

Spring-2018-Manuscript-2.Pdf

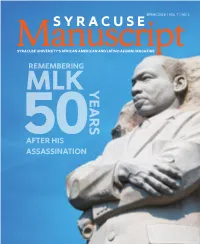

SPRING 2018 | VOL. 7 | NO. 1 SYRACUSE ManuscriptSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY’S AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINO ALUMNI MAGAZINE REMEMBERING MLK YEARS 50AFTER HIS ASSASSINATION CONTENTS Brandyn Munford ’18 and Anjana Pati ’18 presented Angela Rye with a ceramic platter created by Professor Emeritus David MacDonald at SU’s 2018 MLK Celebration. CONTENTS Contents From the ’Cuse ..........................................................................2 Remembering MLK ................................................................3 Stith Leads Norfolk State ....................................................6 Fuller Creates Endowment .................................................7 Vincent H. Cohen Sr. Honored with Named Scholarship ................................................................8 Paris Noir Endowment ..........................................................9 Student Spotlight ............................................................10 OTHC Scholarship Donor List .....................................12 6 Campus News ..................................................................14 3 Alumni News .....................................................................18 CBT Martha’s Vineyard..................................................26 Alumni Milestones ................................................................ 26 In Memoriam .......................................................................... 27 19 7 22 8 15 16 18 10 11 ON THE COVER: Martin Luther Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. RACHEL VASSEL ’91, Assistant -

Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little

The Ensley Athletic Center is the latest major facilities addition to the Lampe Athletics Complex. The $13 million building was constructed in seven months and opened in January 2015. It serves as an indoor training center for the football program, as well as other sports. A multi- million dollar gift from Cliff Ensley, a walk-on who earned a football scholarship and became a three-sport standout at Syracuse in the late 1960s, combined with major gifts from Dick and Jean Thompson, made the construction of the 87,000 square-foot practice facility possible. The construction of Plaza 44, which will The Ensley Athletic Center includes a 7,600 tell the story of Syracuse’s most famous square-foot entry pavilion that houses number, has begun. A gathering area meeting space and restrooms. outside the Ensley Athletic Center made possible by the generosity of Jeff and Jennifer Rubin, Plaza 44 will feature bronze statues of the three men who defi ne the Legend of 44 — Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little. Syracuse defeated Minnesota in the 2013 Texas Bowl for its third consecutive bowl victory and fi fth in its last six postseason trips. Overall, the Orange has earned invitations to every bowl game that is part of the College Football Playoff and holds a 15-9-1 bowl record. Bowl Game (Date) Result Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1953) Alabama 61, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1957) TCU 28, Syracuse 27 Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1959) Oklahoma 21, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1960) Syracuse 23, Texas 14 Liberty Bowl (Dec. -

2010 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL FINAL RELEASE: 8-5 Overall, 4-3 BIG EAST

2010 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL FINAL RELEASE: 8-5 overall, 4-3 BIG EAST Orange Invited to Inaugural Pinstripe Bowl ORANGE SLICES Syracuse University, New York’s College Team, is making history in the Big Apple once again. The Orange will represent The BIG EAST Conference in the first New Era Pinstripe Bowl, playing against Kansas State on Orange on Television Thursday, Dec. 30 at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx (3:30 p.m., ESPN). The New Era Pinstripe Bowl will be televised on ESPN … Bob Wischusen and Brian Griese will call • The Orange earned its first bowl bid since 2004 on the strength of a 7-5 record in Marrone’s second the action from the booth with Eamon McAnaney season. Marrone, a life-long fan of the New York Yankees, is a Bronx native and a 1982 graduate of reporting from the sidelines … Bryan Ryder will Herbert H. Lehman High School, located less than 10 minutes from Yankee Stadium. produce the broadcast. • Marrone’s affinity for the Yankees isn’t his only tie to the 27-time World Series champions. His maternal grandfather, Robert Thompson, worked as an usher at old Yankee Stadium for nearly 20 years. Orange on Radio • Syracuse has a rich football history in New York City and the metropolitan area. The Orange is 5-1 all- Syracuse Sports Network time at Yankee Stadium, including a 3-0 victory against Pittsburgh in 1923 in the first college football Voice of the Orange Matt Park ‘97 and former game ever played there. In addition, the Orange has played seven times at the Polo Grounds in New Orange All-American tight end Chris Gedney York City and taken the field for games at Shea Stadium in Flushing, N.Y. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts SPORT SPECTACLE, ATHLETIC ACTIVISM, AND THE RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF MEDIATED SPORT A Dissertation in English by Kyle R. King 2017 Kyle R. King Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 The dissertation of Kyle R. King was reviewed and approved* by the following: Debra Hawhee Director of Graduate Studies, Department of English McCourtney Professor of Civic Deliberation Professor of English and of Communication Arts and Sciences Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Cheryl Glenn Distinguished Professor of English and Women’s Studies Director, Program in Writing and Rhetoric Rosa Eberly Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Associate Professor of English Kirt H. Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Jaime Schultz Associate Professor of Kinesiology * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Sports is widely regarded as a “spectacle,” an attention-grabbing consumerist distraction from more important elements of social life. Yet this definition underestimates the rhetorical potency of spectacle, as a context in which athletes may participate in projects of social transformation and institutional reform. Sport Spectacle, Athletic Activism, and the Rhetorical Analysis of Mediated Sport engages a set of case studies that assess the rhetorical conditions that empower or sideline athletes in projects of social change. The introduction builds a -

UAB SAM HOUSTON STATE Saturday, August 19 • 7 P.M

2006 OPPONENTS UAB SAM HOUSTON STATE Saturday, August 19 • 7 p.m. CST (Exhibition) Friday, August 25 • 7 p.m. CST Starkville, Miss. • MSU Soccer Field (500) Huntsville, Texas • Holleman Field (600) Paul Harbin F Sally Palmer Marcia Oliveira GK Melissa Sauceda GENERAL INFORMATION MEDIA RELATIONS GENERAL INFORMATION MEDIA RELATIONS Location . .Birmingham, Alabama Soccer Contact . .Michelle Cunningham Location . .Huntsville, Texas Soccer Contact . .Paul Ridings Founded . .1969 Office Phone . .(205) 934-0725 Founded . .1879 Office Phone . .(936) 294-1764 Enrollment . .16,357 Cell Phone . .(205) 417-8145 Enrollment . .15,322 Cell Phone . .TBA Nickname . .Blazers E-Mail . [email protected] Nickname . .Bearkats E-Mail . [email protected] Colors . .Forest Green & Old Gold SID Fax . .(205) 934-7505 Colors . .Orange & White SID Fax . .(936) 294-3538 Conference . .Conference USA Press Box . .n/a Conference . .Southland Press Box . .None President . .Dr. Carol Garrison Web Page . .www.uabsports.com President . .Dr. James F. Gaertner Web Page . .www.GoBearkats.com Athletic Director . .Richard Margison Athletic Director . .Bobby Williams SWA . .Rosalind Ervin SERIES INFORMATION SWA . .n/a SERIES INFORMATION Stadium . .West Campus Field Overall . .UAB leads 3-2-0 Stadium . .Holleman Field Overall . .First meeting Capacity . .2,500 [MSU @ Home: 1-1-0; Away: 1-2-0] Capacity . .600 [MSU @ Home: 0-0-0; Away: 0-0-0] Dept. Phone . .(205) 934-7252 Last MSU win: . .9/30/01 (1-0) Dept. Phone . .(936) 294-1729 Last MSU win: . .n/a Ticket Office . .(205) 934-8001 Last MSU home win: . .9/6/96 (2-0) Ticket Office . .(936) 294-1729 Last MSU home win: . .n/a Last MSU road win: . -

2015 Liberty Volleyball Match Notes - Matches 7-9 Volleyball Schedule Appalachian State Invitational

2015 Liberty 2015 Liberty Volleyball Match Notes - Matches 7-9 Volleyball Schedule Appalachian State Invitational Liberty Invitational Sept. 11, 2015 Aug. 28 UNCG W, 3-0 Aug. 29 FAIR.-DICKINSON W, 3-1 4 p.m. - vs. Charlotte 49ERS (2-4) Aug. 29 HAMPTON W, 3-1 Lumberjack Classic Sept. 12, 2015 Sept. 4 vs. Loyola Marymount L, 0-3 Liberty Sept. 5 at Northern Arizona L, 0-3 12:30 p.m. - at Appalachian State Sept. 5 vs. Houston Baptist W, 3-1 LADY FLAMES (4-2) MOUNTAINEERS (4-3) Appalachian State Invitational Sept. 11 vs. Charlotte 4 p.m. Sept. 12 at Appalachian State 12:30 p.m. 4 p.m. - vs. Missouri TIGERS (6-0) Sept. 12 vs. Missouri 4 p.m. Virginia Tech Invitational Holmes Convocation Center - Boone, N.C. Sept. 18 vs. Chattanooga 4:30 p.m. Sept. 19 vs. Middle Tenn. 12:30 p.m. Liberty (4-2) continues its 10-match road swing this weekend, traveling to Boone, Sept. 19 at Virginia Tech 7 p.m. N.C., for the Appalachian State Invitational. While in Boone, the Lady Flames will face Sept. 25 at Radford * 7 p.m. Charlotte (2-4) on Friday at 4 p.m., before meeting Appalachian State (4-3) and Missouri Oct. 2 GARDNER-WEBB * 7 p.m. Oct. 3 UNC ASHEVILLE * 2 p.m. (6-0) on Saturday. Oct. 6 VCU 6 p.m. The Lady Flames are 5-3 all-time against Charlotte and 2-4 versus Appalachian State. Oct. 9 at Campbell * 7 p.m. Oct. -

College Athletes' Experiences with Identity

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2021 Encroachment: College Athletes’ Experiences with Identity Development as Affected By Media Representations of Social Justice Demonstrations Madison Remi VanWalleghen South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation VanWalleghen, Madison Remi, "Encroachment: College Athletes’ Experiences with Identity Development as Affected By Media Representations of Social Justice Demonstrations" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 5745. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/5745 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENCROACHMENT: COLLEGE ATHLETES’ EXPERIENCES WITH IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT AS AFFECTED BY MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF SOCIAL JUSTICE DEMONSTRATIONS BY MADISON R. VANWALLEGHEN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Major in Communication and Media Studies South Dakota State University 2021 ii THESIS ACCEPTANCE PAGE Madison R. VanWalleghen This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the master’s degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. -

Downloaded from ©2017 College Sport Research Institute

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, 2017, 10, 17-34 17 © 2017 College Sport Research Institute Kick these kids off the team and take away their scholarships: Facebook and perceptions of athlete activism at the University of Missouri __________________________________________________________ Evan Frederick University of Louisville James Sanderson Arizona State University Nicholas Schlereth University of New Mexico __________________________________________________________ The purpose of this study was to examine how individuals responded to a 2015 protest by the University of Missouri football players’ in response to racial injustices on campus and the perceptions associated with this activism. Specifically, comments made to posts on the official University of Missouri Athletic Department Facebook page were analyzed through the theoretical lens of framing and critical race theory. Data were analyzed using constant comparative methodology with critical race theory as a guiding framework. Four themes emerged inductively from the data analysis including (a) trivializing racism; (b) encouraging advocacy; (c) systemic critiques; and (d) incompatibility of advocacy. Comments discussed how college athletes were manufacturing racism and that they should not engage in activism due to its incompatibility with sport. While encouragement existed in the data, some went as far as to suggest that these activism efforts warranted the revocation of the athletes’ scholarship. These comments reinforced dominant ideology of Whiteness in sport by suggesting that athletes should be grateful for their opportunity and not question their place within institutional hierarchies and structures. Keywords: athlete activism, critical race theory, framing, Facebook, athlete advocacy Downloaded from http://csri-jiia.org ©2017 College Sport Research Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. -

Charlotte 49Ers Athletic Foundation Membership Guide

CHARLOTTE 49ERS ATHLETIC FOUNDATION MEMBERSHIP GUIDE MESSAGE FROM THE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR Thank you for your support of the Charlotte 49ers! This membership guide outlines the mission of the Athletic Foundation and the benefits of being a member. Before coming on board, I spoke with people throughout the conference and across the nation, and their assessment was clear -- this is a program with a strong foundation and gold mine potential. Since my arrival, I’ve been visited by friends and colleagues who were able to see campus for the first time – and they have been blown away. What we have here, and what we should be proud of, rivals the campuses and facilities of many schools in “Power Five” conferences. We offer more than beautiful surroundings, though, because in the end, it’s always about our student-athletes. Our track and field team took the lead by winning Conference USA Championships in women’s cross-country, men’s indoor track and men’s outdoor track. Four track and field athletes earned NCAA all-America honors, along with women’s cross country runner Caroline Sang, who claimed both the C-USA and NCAA Southeast Region individual titles. Three student- athletes -- softball’s Haley Pace and Bailey Rhoney and men’s soccer’s Callum Montgomery -- were named CoSIDA Academic all-Americans for displaying excellence on the field and in the classroom. Our student-athletes donated over a record 5,000 hours of community service. In the classroom, we had a Conference USA-high 74 student-athletes earn the Commissioner’s Academic Medal with a cumulative GPA of 3.75 or better.