Sandra Day O'connor College of Law Arizona State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Professional Athlete Career Transition: an Overview of the Literature Keiko Jodai* and Haruo Nogawa*

Career transitions of professional athletes Review : Sociology and Philosophy A study on professional athlete career transition: an overview of the literature Keiko Jodai* and Haruo Nogawa* *Graduate School,School of Sport and Health Science, Juntendo University 1-1, Hiragagakuendai, Inzai, Chiba, 270-1695 Japan [email protected] [Received February 25, 2011 ; Accepted August 22, 2011] Since the 1990’s, there have been many research studies that focus on career transitions for professional athletes in Japan. The main reason for this is that during that period, amateur sports teams, such as soccer and basketball, were spun off from divisions of companies to become separate professional teams. Consequently, this changed forced how athletes view the transition to a second career because they can no longer count on being employed by the companies that had previously run teams as part of their corporate operations. Research studies primarily covered top athletes but did not distinguish between the amateur and professional athletes. In reviewing the assumptions and results of such previous research with respect to professional status, this study will present the basic themes of such research. For example, early research investigated the actual reasons why and how athletes decide to change career; whereas later research seek to study how athletes specifi cally deal with career changes. Finally, in order to determine the effectiveness of actual support programs, the authors of this study proposes that more thorough investigation is needed to scrutinize how the career transitions of ex-professional football players have changed over time by using a “longitudinal” analysis. Keywords: career transitions, professional athletes [Football Science Vol.9, 50-61, 2012] 1. -

Olympic Charter

OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 © International Olympic Committee Château de Vidy – C.P. 356 – CH-1007 Lausanne/Switzerland Tel. + 41 21 621 61 11 – Fax + 41 21 621 62 16 www.olympic.org Published by the International Olympic Committee – July 2020 All rights reserved. Printing by DidWeDo S.à.r.l., Lausanne, Switzerland Printed in Switzerland Table of Contents Abbreviations used within the Olympic Movement ...................................................................8 Introduction to the Olympic Charter............................................................................................9 Preamble ......................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Principles of Olympism .......................................................................................11 Chapter 1 The Olympic Movement ............................................................................................. 15 1 Composition and general organisation of the Olympic Movement . 15 2 Mission and role of the IOC* ............................................................................................ 16 Bye-law to Rule 2 . 18 3 Recognition by the IOC .................................................................................................... 18 4 Olympic Congress* ........................................................................................................... 19 Bye-law to Rule 4 -

Our Goal at Olympia Gymnastics Academy, Inc

Part One: Introduction to Olympia Gymnastics Academy Welcome to the Olympia Gymnastics Academy Team Program Thank you for your interest in Olympia Gymnastics. The adventure you and your child are about to embark on will be a very special one. (Yes, it will be your adventure too!) Over the years, we have had the pleasure of watching many children learn, grow, develop, and mature into confident young adults who are ready to face the world. We look forward to the unique opportunities which working with your child will present. This undertaking will give your child a stage on which to develop his confidence, poise, individuality, mental and physical discipline, determination, appreciation for dedicated effort, and self-respect. Your child will mature among individuals and circumstances that will demand his finest efforts and judgments. He will develop close relationships with other young athletes who demand the best of themselves and expect the best in others. Educational opportunities will be made available which will compliment and enhance the experiences he will have in the gym. Above all, he will have tons of fun! We would like to personally congratulate each and every one of you for choosing gymnastics for your child. Gymnastics is the greatest overall body conditioning activity that you can have your child involved in. A study was done testing the components of physical fitness (strength, flexibility, coordination, etc.) of a number of college athletes involved in various sports. When the totals were added up, gymnasts proved to be the most physically fit. Some of the physical attributes that you will find developing in your young gymnast will be: strength, flexibility, kinesthetic awareness, muscular control, muscular endurance, coordination, timing, explosive power, agility, running speed, balance, and grace. -

Project Selene: AIAA Lunar Base Camp

Project Selene: AIAA Lunar Base Camp AIAA Space Mission System 2019-2020 Virginia Tech Aerospace Engineering Faculty Advisor : Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Team Members : Olivia Arthur, Bobby Aselford, Michel Becker, Patrick Crandall, Heidi Engebreth, Maedini Jayaprakash, Logan Lark, Nico Ortiz, Matthew Pieczynski, Brendan Ventura Member AIAA Number Member AIAA Number And Signature And Signature Faculty Advisor 25807 Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Brendan Ventura 1109196 Matthew Pieczynski 936900 Team Lead/Operations Logan Lark 902106 Heidi Engebreth 1109232 Structures & Environment Patrick Crandall 1109193 Olivia Arthur 999589 Power & Thermal Maedini Jayaprakash 1085663 Robert Aselford 1109195 CCDH/Operations Michel Becker 1109194 Nico Ortiz 1109533 Attitude, Trajectory, Orbits and Launch Vehicles Contents 1 Symbols and Acronyms 8 2 Executive Summary 9 3 Preface and Introduction 13 3.1 Project Management . 13 3.2 Problem Definition . 14 3.2.1 Background and Motivation . 14 3.2.2 RFP and Description . 14 3.2.3 Project Scope . 15 3.2.4 Disciplines . 15 3.2.5 Societal Sectors . 15 3.2.6 Assumptions . 16 3.2.7 Relevant Capital and Resources . 16 4 Value System Design 17 4.1 Introduction . 17 4.2 Analytical Hierarchical Process . 17 4.2.1 Longevity . 18 4.2.2 Expandability . 19 4.2.3 Scientific Return . 19 4.2.4 Risk . 20 4.2.5 Cost . 21 5 Initial Concept of Operations 21 5.1 Orbital Analysis . 22 5.2 Launch Vehicles . 22 6 Habitat Location 25 6.1 Introduction . 25 6.2 Region Selection . 25 6.3 Locations of Interest . 26 6.4 Eliminated Locations . 26 6.5 Remaining Locations . 27 6.6 Chosen Location . -

Ebonics Hearing

S. HRG. 105±20 EBONICS HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SPECIAL HEARING Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±641 cc WASHINGTON : 1997 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa SLADE GORTON, Washington ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho HERB KOHL, Wisconsin KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas PATTY MURRAY, Washington Majority Professional Staff CRAIG A. HIGGINS and BETTILOU TAYLOR Minority Professional Staff MARSHA SIMON (II) 2 CONTENTS Page Opening remarks of Senator Arlen Specter .......................................................... -

The Heritage Foundation 1314 Cleveland Street John, Barbara

PAUL J. LARKIN, JR. CURRICULUM VITAE The Heritage Foundation 1314 Cleveland Street John, Barbara & Victoria Rumpel Alexandria, VA 22302 Senior Legal Research Fellow M: 703-887-9599 214 Massachusetts Ave., NE E: [email protected] Washington, DC 20002 O: 202-608-6190 E: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT The Heritage Foundation: John, Barbara & Victoria Rumpel Senior Legal Research Fellow at the Meese Center of the Heritage Foundation Institute for Constitutional Government, 2018; Senior Le- gal Research Fellow, 2011-2018; Manager, Overcriminalization Project: 2011-2016 Federal Bureau of Investigation: Counsel to the Program Director, Office for Victim Assistance: 2011; Special Assistant to the Assistant Director for Professional Responsibility: 2010-2011 Federal Trade Commission: Office of the General Counsel, Attorney: 2010 Verizon Communications Inc.: Assistant General Counsel: 2004-2009 Environmental Protection Agency, Criminal Investigation Division: Acting Director, Criminal Investigation Division: 2003-2004; Special Agent-in-Charge: 2002-2004; Associate Special Agent- in-Charge: 2001-2002; Special Agent: 1998-2001 United States Senate Environment & Public Works Committee: Majority Fellow: 2000 United States Senate Judiciary Committee: Counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee and Chief of the Crime Unit: 1996-1997 King & Spalding: Of Counsel: 1994-1996 Office of the Independent Counsel (Department of Housing & Urban Development Investigation): Associate Independent Counsel: 1995-1996 Office of the Solicitor General, United States Department of Justice: Assistant to the Solicitor General: 1985-1993 Organized Crime and Racketeering Section, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice: Attorney: 1984-1985 Hogan & Hartson (now Hogan Lovells): Law firm associate: 1982-1984 Law Clerk to the Honorable Robert H. Bork, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit: 1982 Law Clerk to the Honorable Robert A. -

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES Oriole Park at Camden Yards 333 West Camden Street Baltimore, MD 21201

BALTIMORE ORIOLES GAME NOTES Oriole Park at Camden Yards 333 West Camden Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Saturday, September 27, 2014 Game #161 Road Game #80 Baltimore Orioles (95-65) vs. Toronto Blue Jays (82-78) LH Wei-Yin Chen (16-5, 3.56) vs. LH J.A. Happ (10-11, 4.27) TONIGHT’S GAME: The AL East champion Orioles face the Blue Jays in the middle game of their regular BEST RECORD IN MLB season-ending series, the sixth game of a seven-game trip that began with the O’s splitting four games in the th TEAM W L PCT Bronx…The Orioles have the best record in baseball since June 30 (53-26, .671) and are the 20 club in team Los Angeles (AL) 98 62 .613 history to win 90+ games…The Orioles currently lead the division by 12.0 games and will be the first team since BALTIMORE (AL) 95 65 .594 the 2006 Yankees (10.0 games) to win the AL East by a double digit margin. Washington (NL) 94 66 .588 VS. TORONTO: The Orioles lead the season series, 10-7, going 6-4 in Baltimore and 4-3 in Toronto…In 2013, ODDS & ENDS the Orioles won the season series, 10-9, as they went 6-3 in Baltimore and 4-6 in Toronto…The Orioles trail in the Home 50-31 all-time series, 262-298 (149-134 in Baltimore and 113-164 in Toronto)…Per STATS, the Orioles have never Away 45-34 won more than 11 games vs. Toronto in a single-season (won club record 11 in 2012, 2004, 1980, and 1979). -

Spring-2018-Manuscript-2.Pdf

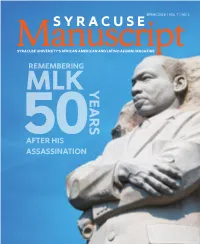

SPRING 2018 | VOL. 7 | NO. 1 SYRACUSE ManuscriptSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY’S AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINO ALUMNI MAGAZINE REMEMBERING MLK YEARS 50AFTER HIS ASSASSINATION CONTENTS Brandyn Munford ’18 and Anjana Pati ’18 presented Angela Rye with a ceramic platter created by Professor Emeritus David MacDonald at SU’s 2018 MLK Celebration. CONTENTS Contents From the ’Cuse ..........................................................................2 Remembering MLK ................................................................3 Stith Leads Norfolk State ....................................................6 Fuller Creates Endowment .................................................7 Vincent H. Cohen Sr. Honored with Named Scholarship ................................................................8 Paris Noir Endowment ..........................................................9 Student Spotlight ............................................................10 OTHC Scholarship Donor List .....................................12 6 Campus News ..................................................................14 3 Alumni News .....................................................................18 CBT Martha’s Vineyard..................................................26 Alumni Milestones ................................................................ 26 In Memoriam .......................................................................... 27 19 7 22 8 15 16 18 10 11 ON THE COVER: Martin Luther Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. RACHEL VASSEL ’91, Assistant -

Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little

The Ensley Athletic Center is the latest major facilities addition to the Lampe Athletics Complex. The $13 million building was constructed in seven months and opened in January 2015. It serves as an indoor training center for the football program, as well as other sports. A multi- million dollar gift from Cliff Ensley, a walk-on who earned a football scholarship and became a three-sport standout at Syracuse in the late 1960s, combined with major gifts from Dick and Jean Thompson, made the construction of the 87,000 square-foot practice facility possible. The construction of Plaza 44, which will The Ensley Athletic Center includes a 7,600 tell the story of Syracuse’s most famous square-foot entry pavilion that houses number, has begun. A gathering area meeting space and restrooms. outside the Ensley Athletic Center made possible by the generosity of Jeff and Jennifer Rubin, Plaza 44 will feature bronze statues of the three men who defi ne the Legend of 44 — Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little. Syracuse defeated Minnesota in the 2013 Texas Bowl for its third consecutive bowl victory and fi fth in its last six postseason trips. Overall, the Orange has earned invitations to every bowl game that is part of the College Football Playoff and holds a 15-9-1 bowl record. Bowl Game (Date) Result Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1953) Alabama 61, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1957) TCU 28, Syracuse 27 Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1959) Oklahoma 21, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1960) Syracuse 23, Texas 14 Liberty Bowl (Dec. -

SJSU Student Arrested on Drug Charges

Focus SpoRTs Happy Softball loses St. Patrick's to UNLV; prepares Day! for NISI' See related story... See page 6... Volume 101, Number :16 PARTANPublished for San Jose State t I tiiIi'r %I,. ii i 7, i99.1 niversit since 1931 DAILY SJSU student arrested on drug charges By Cristal Guderjahn with possession of a controlled Brown said Thursday. "The signed by a judge who has rea- Lt. Lowe would riot release out in the hallway It was like a Spartan Daily Staff writer substance. Giver was booked police think (Giver) is some son to believe that the informa- details of the arrest or identify movie." A 19-year-old San Jose State into the Santa Clara County Jail kind of big-time drug dealer. tion in the warrant is valid and the controlled substance Giver The arrest was the result of a University student was arrested in San Jose. They came in and busted up our trustworthy," Lowe said. "A sim- allegedly had in his possession. San Jose Police Department on drug charges Tuesday morn- Giver's roommate, SJSU fresh- room, but there is not one bit of ple phone call is not going to be Brown said the police found two investigation, Lowe said. The ing in Joe West Hall on Ninth man Jake Brown, 18, said police coke in this dorm." sufficient in and of itself to lead doses, called "hits," of LSD in University Police, which assist- Street, said Lt. Bruce Lowe of officers broke down his door Police had a search warrant to the issuance of a search war- the room, but no cocaine. -

APBA Pro Baseball 2015 Carded Player List

APBA Pro Baseball 2015 Carded Player List ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CINCINNATI COLORADO LOS ANGELES Ender Inciarte Jace Peterson Dexter Fowler Billy Hamilton Charlie Blackmon Jimmy Rollins A. J. Pollock Cameron Maybin Jorge Soler Joey Votto Jose Reyes Howie Kendrick Paul Goldschmidt Freddie Freeman Kyle Schwarber Todd Frazier Carlos Gonzalez Justin Turner David Peralta Nick Markakis Kris Bryant Brandon Phillips Nolan Arenado Adrian Gonzalez Welington Castillo Adonis Garcia Anthony Rizzo Jay Bruce Ben Paulsen Yasmani Grandal Yasmany Tomas Nick Swisher Starlin Castro Brayan Pena Wilin Rosario Andre Ethier Jake Lamb A.J. Pierzynski Chris Coghlan Ivan DeJesus D.J. LeMahieu Yasiel Puig Chris Owings Christian Bethancourt Austin Jackson Eugenio Suarez Nick Hundley Scott Van Slyke Aaron Hill Andrelton Simmons Miguel Montero Tucker Barnhart Michael McKenry Alex Guerrero Nick Ahmed Michael Bourn David Ross Skip Schumaker Brandon Barnes Kike Hernandez Tuffy Gosewisch Pedro Ciriaco Addison Russell Zack Cozart Justin Morneau Carl Crawford Jarrod Saltalamacchia Daniel Castro Jonathan Herrera Kris Negron Kyle Parker Joc Pederson Jordan Pacheco Hector Olivera Javier Baez Jason Bourgeois Daniel Descalso A. J. Ellis Brandon Drury Eury Perez Chris Denorfia Brennnan Boesch Rafael Ynoa Chase Utley Phil Gosselin Todd Cunningham Matt Szczur Anthony DeSclafani Corey Dickerson Corey Seager Rubby De La Rosa Shelby Miller Jake Arrieta Michael Lorenzen Kyle Kendrick Clayton Kershaw Chase Anderson Julio Teheran Jon Lester Raisel Iglesias Jorge De La Rosa Zack Greinke Jeremy Hellickson Williams Perez Dan Haren Keyvius Sampson Chris Rusin Alex Wood Robbie Ray Matt Wisler Kyle Hendricks John Lamb Chad Bettis Brett Anderson Patrick Corbin Mike Foltynewicz Jason Hammel Burke Badenhop Eddie Butler Mike Bolsinger Archie Bradley Eric Stults Tsuyoshi Wada J. -

2010 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL FINAL RELEASE: 8-5 Overall, 4-3 BIG EAST

2010 SYRACUSE FOOTBALL FINAL RELEASE: 8-5 overall, 4-3 BIG EAST Orange Invited to Inaugural Pinstripe Bowl ORANGE SLICES Syracuse University, New York’s College Team, is making history in the Big Apple once again. The Orange will represent The BIG EAST Conference in the first New Era Pinstripe Bowl, playing against Kansas State on Orange on Television Thursday, Dec. 30 at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx (3:30 p.m., ESPN). The New Era Pinstripe Bowl will be televised on ESPN … Bob Wischusen and Brian Griese will call • The Orange earned its first bowl bid since 2004 on the strength of a 7-5 record in Marrone’s second the action from the booth with Eamon McAnaney season. Marrone, a life-long fan of the New York Yankees, is a Bronx native and a 1982 graduate of reporting from the sidelines … Bryan Ryder will Herbert H. Lehman High School, located less than 10 minutes from Yankee Stadium. produce the broadcast. • Marrone’s affinity for the Yankees isn’t his only tie to the 27-time World Series champions. His maternal grandfather, Robert Thompson, worked as an usher at old Yankee Stadium for nearly 20 years. Orange on Radio • Syracuse has a rich football history in New York City and the metropolitan area. The Orange is 5-1 all- Syracuse Sports Network time at Yankee Stadium, including a 3-0 victory against Pittsburgh in 1923 in the first college football Voice of the Orange Matt Park ‘97 and former game ever played there. In addition, the Orange has played seven times at the Polo Grounds in New Orange All-American tight end Chris Gedney York City and taken the field for games at Shea Stadium in Flushing, N.Y.