Hook Echoes and Rear-Flank Downdrafts: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast

Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast John T. Snow Regents’ Professor of Meteorology Dean Emeritus, College of Atmospheric and Geographic Sciences, The University of Oklahoma Major contributions from: Dr. Russel Schneider –NOAA Storm Prediction Center Dr. David Stensrud – NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Dr. Ming Xue –Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, University of Oklahoma Dr. Lou Wicker –NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Hazards Caucus Alliance Briefing Tornadoes: Understanding how they develop and providing early warning 10:30 am – 11:30 am, Wednesday, 21 July 2010 Senate Capitol Visitors Center 212 Each Year: ~1,500 tornadoes touch down in the United States, causing over 80 deaths, 100s of injuries, and an estimated $1.1 billion in damages Statistics from NOAA Storm Prediction Center Supercell –A long‐lived rotating thunderstorm the primary type of thunderstorm producing strong and violent tornadoes Present Warning System: Warn on Detection • A Warning is the culmination of information developed and distributed over the preceding days sequence of day‐by‐day forecasts identifies an area of high threat •On the day, storm spotters deployed; radars monitor formation, growth of thunderstorms • Appearance of distinct cloud or radar echo features tornado has formed or is about to do so Warning is generated, distributed Present Warning System: Warn on Detection Radar at 2100 CST Radar at 2130 CST with Warning Thunderstorms are monitored using radar A warning is issued based on the detected and -

Downloaded 09/30/21 06:43 PM UTC JUNE 1996 MONTEVERDI and JOHNSON 247

246 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 11 A Supercell Thunderstorm with Hook Echo in the San Joaquin Valley, California JOHN P. MONTEVERDI Department of Geosciences, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California STEVE JOHNSON Association of Central California Weather Observers, Fresno, California (Manuscript received 30 January 1995, in ®nal form 9 February 1996) ABSTRACT This study documents a damaging supercell thunderstorm that occurred in California's San Joaquin Valley on 5 March 1994. The storm formed in a ``cold sector'' environment similar to that documented for several other recent Sacramento Valley severe thunderstorm events. Analyses of hourly subsynoptic surface and radar data suggested that two thunderstorms with divergent paths developed from an initial echo that had formed just east of the San Francisco Bay region. The southern storm became severe as it ingested warmer, moister boundary layer air in the south-central San Joaquin Valley. A well-developed hook echo with a 63-dBZ core was observed by a privately owned 5-cm radar as the storm passed through the Fresno area. Buoyancy parameters and ho- dograph characteristics were obtained both for estimated conditions for Fresno [on the basis of a modi®ed morning Oakland (OAK) sounding] and for the actual storm environment (on the basis of a radiosonde launched from Lemoore Naval Air Station at about the time of the storm's passage through the Fresno area). Both the estimated and actual hodographs essentially were straight and suggested storm splitting. Although the actual CAPE was similar to that which was estimated, the observed magnitude of the low-level shear was considerably greater than the estimate. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Tornadogenesis in a Simulated Mesovortex Within a Mesoscale Convective System

3372 JOURNAL OF THE ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES VOLUME 69 Tornadogenesis in a Simulated Mesovortex within a Mesoscale Convective System ALEXANDER D. SCHENKMAN,MING XUE, AND ALAN SHAPIRO Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, and School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 3 February 2012, in final form 23 April 2012) ABSTRACT The Advanced Regional Prediction System (ARPS) is used to simulate a tornadic mesovortex with the aim of understanding the associated tornadogenesis processes. The mesovortex was one of two tornadic meso- vortices spawned by a mesoscale convective system (MCS) that traversed southwestern and central Okla- homa on 8–9 May 2007. The simulation used 100-m horizontal grid spacing, and is nested within two outer grids with 400-m and 2-km grid spacing, respectively. Both outer grids assimilate radar, upper-air, and surface observations via 5-min three-dimensional variational data assimilation (3DVAR) cycles. The 100-m grid is initialized from a 40-min forecast on the 400-m grid. Results from the 100-m simulation provide a detailed picture of the development of a mesovortex that produces a submesovortex-scale tornado-like vortex (TLV). Closer examination of the genesis of the TLV suggests that a strong low-level updraft is critical in converging and amplifying vertical vorticity associated with the mesovortex. Vertical cross sections and backward trajectory analyses from this low-level updraft reveal that the updraft is the upward branch of a strong rotor that forms just northwest of the simulated TLV. The horizontal vorticity in this rotor originates in the near-surface inflow and is caused by surface friction. -

Near-Surface Vortex Structure in a Tornado and in a Sub-Tornado-Strength Convective-Storm Vortex Observed by a Mobile, W-Band Radar During VORTEX2

VOLUME 141 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW NOVEMBER 2013 Near-Surface Vortex Structure in a Tornado and in a Sub-Tornado-Strength Convective-Storm Vortex Observed by a Mobile, W-Band Radar during VORTEX2 ,1 # @ ROBIN L. TANAMACHI,* HOWARD B. BLUESTEIN, MING XUE,* WEN-CHAU LEE, & & @ KRZYSZTOF A. ORZEL, STEPHEN J. FRASIER, AND ROGER M. WAKIMOTO * Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, and School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma # School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma @ National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado & Microwave Remote Sensing Laboratory, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts (Manuscript received 14 November 2012, in final form 22 May 2013) ABSTRACT As part of the Second Verification of the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment (VORTEX2) field campaign, a very high-resolution, mobile, W-band Doppler radar collected near-surface (#200 m AGL) observations in an EF-0 tornado near Tribune, Kansas, on 25 May 2010 and in sub-tornado-strength vortices near Prospect Valley, Colorado, on 26 May 2010. In the Tribune case, the tornado’s condensation funnel dissipated and then reformed after a 3-min gap. In the Prospect Valley case, no condensation funnel was observed, but evidence from the highest-resolution radars in the VORTEX2 fleet indicates multiple, sub-tornado-strength vortices near the surface, some with weak-echo holes accompanying Doppler velocity couplets. Using high-resolution Doppler radar data, the authors document the full life cycle of sub- tornado-strength vortex beneath a convective storm that previously produced tornadoes. The kinematic evolution of these vortices, from genesis to decay, is investigated via ground-based velocity track display (GBVTD) analysis of the W-band velocity data. -

The Origins of Vortex Sheets in a Simulated Supercell Thunderstorm

3944 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 142 The Origins of Vortex Sheets in a Simulated Supercell Thunderstorm PAUL MARKOWSKI AND YVETTE RICHARDSON Department of Meteorology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania GEORGE BRYAN Mesoscale and Microscale Meteorology Division, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado (Manuscript received 23 May 2014, in final form 16 July 2014) ABSTRACT This paper investigates the origins of the (cyclonic) vertical vorticity within vortex sheets that develop within a numerically simulated supercell in a nonrotating, horizontally homogeneous environment with a free-slip lower boundary. Vortex sheets are commonly observed along the gust fronts of supercell storms, particularly in the early stages of storm development. The ‘‘collapse’’ of a vortex sheet into a compact vortex is often seen to accompany the intensification of rotation that occasionally leads to tornadogenesis. The vortex sheets predominantly acquire their vertical vorticity from the tilting of horizontal vorticity that has been modified by horizontal buoyancy gradients associated with the supercell’s cool low-level outflow. If the tilting is within an ascending airstream (i.e., the horizontal gradient of vertical velocity responsible for the tilting resides entirely within an updraft), the vertical vorticity of the vortex sheet nearly vanishes at the lowest model level for horizontal winds (5 m). However, if the tilting occurs within a descending airstream (i.e., the hori- zontal gradient of vertical velocity responsible for tilting includes a downdraft adjacent to the updraft within which the majority of the cyclonic vorticity resides), the vortex sheet extends to the lowest model level. The findings are consistent with the large body of prior work that has found that downdrafts are necessary for the development of significant vertical vorticity at the surface. -

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE of DUPAGE METEOROLOGY Focus on Anticipating and Spotting

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE OF DUPAGE METEOROLOGY HTTP://WEATHER.COD.EDU Focus on Anticipating and Spotting • What do you look for? • What will you actually see? • Can you identify what is going on with the storm? Is Gilbert married? Hmmmmm….rumor has it….. Its all about the updraft! Not that easy! • Various types of storms and storm structures. • A tornado is a “big sucky • Obscuration of important thing” and underneath the features make spotting updraft is where it forms. difficult. • So find the updraft! • The closer you are to a storm the more difficult it becomes to make these identifications. Conceptual models Reality is much harder. Basic Conceptual Model Sometimes its easy! North Central Illinois, 2-28-17 (Courtesy of Matt Piechota) Other times, not so much. Reality usually is far more complicated than our perfect pictures Rain Free Base Dusty Outflow More like reality SCUD Scattered Cumulus Under Deck Sigh...wall clouds! • Wall clouds help spotters identify where the updraft of a storm is • Wall clouds may or may not be present with tornadic storms • Wall clouds may be seen with any storm with an updraft • Wall clouds may or may not be rotating • Wall clouds may or may not result in tornadoes • Wall clouds should not be reported unless there is strong and easily observable rotation noted • When a clear slot is observed, a well written or transmitted report should say as much Characteristics of a Tornadic Wall Cloud • Surface-based inflow • Rapid vertical motion (scud-sucking) • Persistent • Persistent rotation Clear Slot • The key, however, is the development of a clear slot Prof. -

Radar Artifacts and Associated Signatures, Along with Impacts of Terrain on Data Quality

Radar Artifacts and Associated Signatures, Along with Impacts of Terrain on Data Quality 1.) Introduction: The WSR-88D (Weather Surveillance Radar designed and built in the 80s) is the most useful tool used by National Weather Service (NWS) Meteorologists to detect precipitation, calculate its motion, estimate its type (rain, snow, hail, etc) and forecast its position. Radar stands for “Radio, Detection, and Ranging”, was developed in the 1940’s and used during World War II, has gone through numerous enhancements and technological upgrades to help forecasters investigate storms with greater detail and precision. However, as our ability to detect areas of precipitation, including rotation within thunderstorms has vastly improved over the years, so has the radar’s ability to detect other significant meteorological and non meteorological artifacts. In this article we will identify these signatures, explain why and how they occur and provide examples from KTYX and KCXX of both meteorological and non meteorological data which WSR-88D detects. KTYX radar is located on the Tug Hill Plateau near Watertown, NY while, KCXX is located in Colchester, VT with both operated by the NWS in Burlington. Radar signatures to be shown include: bright banding, tornadic hook echo, low level lake boundary, hail spikes, sunset spikes, migrating birds, Route 7 traffic, wind farms, and beam blockage caused by terrain and the associated poor data sampling that occurs. 2.) How Radar Works: The WSR-88D operates by sending out directional pulses at several different elevation angles, which are microseconds long, and when the pulse intersects water droplets or other artifacts, a return signal is sent back to the radar. -

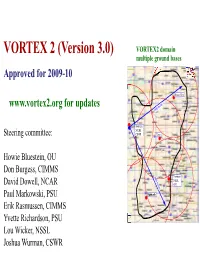

Version 3.0) VORTEX2 Domain Multiple Ground Bases Approved for 2009-10

VORTEX 2 (Version 3.0) VORTEX2 domain multiple ground bases Approved for 2009-10 Sioux City www.vortex2.org for updates Boulder NCAR Steering committee: CSWR Hays Howie Bluestein, OU Don Burgess, CIMMS Norman NSSL David Dowell, NCAR OU Paul Markowski, PSU Lub b o c k Erik Rasmussen, CIMMS Yvette Richardson, PSU Lou Wicker, NSSL Joshua Wurman, CSWR Rapid-Scan DOW SMART-Radar UAV DOW NOXP (XPOL) W-Band Fig. 3.2 RECUV UAV being readied for flight. A variety of instruments, focusing on mesoscale observations, radar, and direct T, RH, wind (others likely to be proposed too) Probes Sticknet DOWs Mesonets Tethered pre-storm Tethered Phase, in OK K V N 4/1-5/10 X KT Takes advantage of LX stationary assets like the Norman Phased-Array 0 25 km CASA, etc. N K O U (fixed radars not shown in order to improve clarity) K F WSR-88D dual- NWRT-PAR CASA mobile radar D coverage polarimetric coverage at X-band radar coverage at stick net R at 1 km AGL WSR-88D 1 km AGL coverage at 250 m AGL Oklahoma coverage 250 m AGL Studies larger mesoscale at 1 km AGL TDWR fixed site mobile Texas coverage at Oklahoma Ft. Cobb Little Washita rawinsonde rawinsonde 250 m AGL mesonet ARS micronet ARS micronet 0 50 100 km site ASOS wind profiler mobile mesonet UAV Cell merger precipitation gust front K supercell forward flank region V N X anvil edge KT LX precipitation gust front 0 5km K O U N (radars not shown in order to improve clarity) K F WSR-88D dual- NWRT-PAR CASA mobile radar D coverage polarimetric coverage at X-band radar coverage at stick net at 1 km AGL WSR-88D 1 km AGL coverage at R 250 m AGL Oklahoma coverage 250 m AGL at 1 km AGL TDWR fixed site mobile Texas coverage at Oklahoma Ft. -

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms -A- Anvil The flat, spreading top of a cloud, often shaped like an anvil. Thunderstorm anvils may spread hundreds of miles downwind from the thunderstorm itself, and sometimes may spread upwind. Anvil Dome A large overshooting top or penetrating top. -B- Back-building Thunderstorm A thunderstorm in which new development takes place on the upwind side (usually the west or southwest side), such that the storm seems to remain stationary or propagate in a backward direction. Back-sheared Anvil [Slang], a thunderstorm anvil which spreads upwind, against the flow aloft. A back-sheared anvil often implies a very strong updraft and a high severe weather potential. Beaver ('s) Tail [Slang], a particular type of inflow band with a relatively broad, flat appearance suggestive of a beaver's tail. It is attached to a supercell's general updraft and is oriented roughly parallel to the pseudo-warm front, i.e., usually east to west or southeast to northwest. As with any inflow band, cloud elements move toward the updraft, i.e., toward the west or northwest. Its size and shape change as the strength of the inflow changes. Spotters should note the distinction between a beaver tail and a tail cloud. A "true" tail cloud typically is attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same level as the wall cloud itself. A beaver tail, on the other hand, is not attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same height as the updraft base (which by definition is higher than the wall cloud). -

The Garden City, Kansas, Storm During VORTEX 95. Part I: Overview of the Storm’S Life Cycle and Mesocyclogenesis

The Garden City, Kansas, storm during VORTEX 95. Part I: Overview of the Storm’s life cycle and mesocyclogenesis Roger M. Wakimoto, Chinghwang Liu, Huaquing Cai Mon. Wea. Rev., 126, 372-392 The Garden City, Kansas, storm during VORTEX 95. Part II: The Wall Cloud and Tornado Roger M. Wakimoto, Chinghwang Liu Mon. Wea. Rev., 126, 393-408 Severe storm environment: Large CAPE and strong low level speed shear. Shear vector unidirectional with height, Helicity small. Trough and wind shift Intersection – focal point for storm initiation Dry line Visible satellite images Note warm inflow switches to cool outflow, probably in rear flank downdraft region Key observing system: ELDORA airborne dual-Doppler radar Flew at 300 m altitude next to the supercell and scanned with both antennas toward supercell PossiblePossible hook hook Tornado damage track Eldora aircraft track: Aircraft flying 300 m above surface Reflectivity (> 40 dBZ shaded), storm relative winds Heavy precipitation Uniform winds near surface Fine line in reflectivity field, believed to be synoptic scale trough line Updraft Cyclonic and anticyclonic mesocyclones aloft (splitting cells) Vertical velocity (gray) and vertical vorticity (dark) Reflectivity (> 40 dBZ shaded), storm relative winds Northerly winds start to develop Downdrafts in heavier precipitation Low level updraft intensifies Low level mesocyclone develops Cyclonic and anticyclonic cells continue to separate 30 m/s updraft becoming near coincident with cyclonic mesocyclone Vertical velocity (gray) and vertical vorticity -

Tornadoes – Forecasting, Dynamics and Genesis

Tornadoes – forecasting, dynamics and genesis Mteor 417 – Iowa State University – Week 12 Bill Gallus Tools to diagnose severe weather risks • Definition of tornado: A vortex (rapidly rotating column of air) associated with moist convection that is intense enough to do damage at the ground. • Note: Funnel cloud is merely a cloud formed by the drop of pressure inside the vortex. It is not needed for a tornado, but usually is present in all but fairly dry areas. • Intensity Scale: Enhanced Fujita scale since 2007: • EF0 Weak 65-85 mph (broken tree branches) • EF1 Weak 86-110 mph (trees snapped, windows broken) • EF2 Strong 111-135 mph (uprooted trees, weak structures destroyed) • EF3 Strong 136-165 mph (walls stripped off buildings) • EF4 Violent 166-200 mph (frame homes destroyed) • EF5 Violent > 200 mph (steel reinforced buildings have major damage) Supercell vs QLCS • It has been estimated that 60% of tornadoes come from supercells, with 40% from QLCS systems. • Instead of treating these differently, we will concentrate on mesocyclonic versus non- mesocyclonic tornadoes • Supercells almost always produce tornadoes from mesocyclones. For QLCS events, it is harder to say what is happening –they may end up with mesocyclones playing a role, but usually these are much shorter lived. Tornadoes - Mesocyclone-induced a) Usually occur within rotating supercells b) vertical wind shear leads to horizontal vorticity which is tilted by the updraft to produce storm rotation, which is stretched by the updraft into a mesocyclone with scales of a few