Aborigines Their Present Condition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

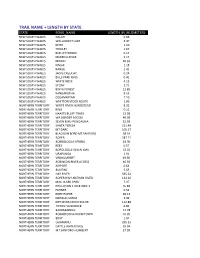

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

Aeromagnetic Data Acquisition by Geoscience Australia & States

AEROMAGNETIC DATA ACQUISITION BY GEOSCIENCE AUSTRALIA & STATES 120°E 126°E 132°E 138°E 144°E 150°E 8°S 8°S BOIGU DARU MAER TORRES STRAIT COBOURG PENINSULA JUNCTION BAY BATHURST ISLAND MELVILLE ISLAND WESSEL ISLANDS TRUANT ISLAND JARDINE RIVER ORFORD BAY ALLIGATOR RIVER MILINGIMBI FOG BAY DARWIN ARNHEM BAY GOVE WEIPA CAPE WEYMOUTH MOUNT EVELYN MOUNT MARUMBA CAPE SCOTT PINE CREEK BLUE MUD BAY PORT LANGDON 12°S LONDONDERRY AURUKUN 12°S COEN FERGUSSON RIVER KATHERINE URAPUNGA ROPER RIVER CAPE BEATRICE MEDUSA BANKS PORT KEATS DRYSDALE HOLROYD MONTAGUE SOUND EBAGOOLA BROWSE ISLAND CAPE MELVILLE DELAMERE LARRIMAH HODGSON DOWNS MOUNT YOUNG PELLEW CAMBRIDGE GULF AUVERGNE ASHTON RUTLAND PLAINS PRINCE REGENT HANN RIVER CAMDEN SOUND COOKTOWN DALY WATERS TANUMBIRINI BAUHINIA DOWNS WATERLOO VICTORIA RIVER DOWNS ROBINSON RIVER MORNINGTON LISSADELL CAPE VAN DIEMEN MOUNT ELIZABETH GALBRAITH CHARNLEY WALSH YAMPI MOSSMAN PENDER CAIRNS BEETALOO LIMBUNYA WAVE HILL NEWCASTLE WATERS WALHALLOW CALVERT HILLS DIXON RANGE WESTMORELAND BURKETOWN LANSDOWNE NORMANTON 16°S 16°S LENNARD RIVER RED RIVER DERBY ATHERTON BROOME INNISFAIL SOUTH LAKE WOODS HELEN SPRINGS BRUNETTE DOWNS BIRRINDUDU WINNECKE CREEK MOUNT DRUMMOND LAWN HILL GORDON DOWNS DONORS HILL MOUNT RAMSAY CROYDON NOONKANBAH GEORGETOWN MOUNT ANDERSON EINASLEIGH LAGRANGE INGHAM TENNANT CREEK TANAMI TANAMI EAST GREEN SWAMP WELL ALROY RANKEN BILLILUNA CAMOOWEAL DOBBYN MOUNT BANNERMAN MILLUNGERA CROSSLAND GILBERTON MCLARTY HILLS CLARKE RIVER MUNRO TOWNSVILLE MANDORA AYR BEDOUT ISLAND BONNEY WELL THE GRANITES MOUNT -

Australia Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Australia: Topographic maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific. Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage. Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one. Coverage of Australian States – All states held. The numbering of the maps represents a grid system. The first two letters, eg SD represent north-south with the second letter increasing south of the Equator. The next numbers, eg 56 represent east-west and increase from west to east. Index maps at bottom of page SC 52 Melville Island (NT) SC-52-16 SC 53 Coburg Penin (NT) SC-53-13 Junction Bay (NT) SC-53-14 Wessel Islands (NT) SC-53-15 Truant Island (NT) SC-53-16 SC 54 Daru (Q) SC-54-8 Thursday Island (Q) SC-54-11 Cape York (Q) SC-54-12 Jardine River (Q) SC-54-15 Orford Bay (Q) SC-54-16 SC 55 Maer (Q) SC-55-5 SD 51 Long Reef (WA) SD-51-08 Browse Island (WA) SD-51-11 Montague Sound (WA) SD-51-12 Camden Sound (WA) SD-51-15 Prince Regent (WA) SD-51-16 Page 1 of 22 Last updated May 2013 University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Australia: Topographic maps 1: 250,000 SD 52 Fog Bay (NT) SD-52-03 Darwin (NT) SD-52-04 Londonderry (WA) SD-52-05 Cape Scott (NT) SD-52-07 Pine Creek (NT) SD-52-08 Drysdale (WA) SD-52-09 Medusa Banks (WA) SD-52-10 Port Keats (NT) SD-52-11 Fergusson River (NT) SD-52-12 Ashton (WA) SD-52-13 Cambridge Gulf (WA) SD-52-14 Auvergne (NT) SD-52-15 -

Fish of the Lake Eyre Catchment of Central Australia

fish of the lake eyre catchment of central australia lake eyre 1 Rob Wager & Peter J. Unmack Department of Primary Industries Queensland Fisheries Service 2 lake eyre LAKE EYRE ZONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE In recognition of the decentralised nature of fishing activities in Queensland, ten regionally based Zonal Advisory Committees (ZAC) were set up to advise the Queensland Fisheries Management Authority (QFMA) on local issues relating to fisheries management and fish habitats. The Lake Eyre ZAC was established by the QFMA to provide: a forum for discussion on regional fisheries and fisheries habitat issues; a vital two-way information flow between fisheries mangers and the community. ZAC membership is diverse, representing fisher groups and associations, conservation groups, tourism, fish stocking groups, local government, other government agencies, and other bodies with an interest in fisheries management and fish habitat issues. © Department of Primary Industries, Queensland, and Queensland Fisheries Management Authority 2000 Disclaimer This document has been prepared by the authors on behalf of the Queensland Fisheries Lake Eyre Zonal Advisory Committee. Opinions expressed are those of the authors. Acknowledgments for the photographs provided by G. E. Schmida and Ross Felix. NOTE: The management arrangements described in this document were accurate at the time of publication. Changes in these management arrangements may occur from time to time. Persons with any questions regarding fisheries management should contact the local office of -

List of Northern Territory Birds

WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SPECIAL PUBLICA TIO N No. 4 LIST OF NORTHERN TERRITORY BIRDS World List Abbreviation : Spec. Publ. W. Aust. Mus. Printed for the Western Australian Museum Board by the Government Printer, Perth, Western Austral,ia. Iss~ecl 28th February, 1967 Edited by w. D. L. RIDE and A. NEUMANN RED- WINGED PARROT Photograph by Mr. Peter Slater LIST OF NORTHERN TERRITORY BIRDS BY G. M. STORR [2]-13314 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 7 Classification ... 7 Distribution ... 8 Status, habitat and breeding season 8 Appendices 9 LIST OF BIRDS 11 BIBLIOGRAPHY 65 SPECIES CONFIRMANDAE .... 69 GAZETTEER .... 71 INDEX TO SPECIES .. 84 Introduction It has long been the desire of ornithologists to have a list of Australian birds with their known range set out with considerably more precision than in current checklists. Yet it is hard to see how such a list can be compiled until each of the states and territories has a list of its own. Several state lists have appeared in the last two decades, and the only large gaps remaining are the birds of Queensland and the Northern Territory. In choosing the second as my subject, I have undertaken much the lighter task; for the avi fauna of the Territory is impoverished compared to Queensland's, and its literature is far smaller. The present work is a compendium of what has been published on the occurrence, status, habitat and breeding season of Northern Territory birds, augmented with my own field notes and those of Dr. D. L. Serventy. No attempt has been made to fill the numerous gaps in the record by writing to museums and observers for information or by personally exploring un worked regions. -

GEOLOGICAL MAP of the NORTHERN TERRITORY TERTIARY Cz Fluvial Sandstone and Siltstone on Bathurst and Melville Islands

Ma Sand, silt and clay in coastal esturies 0 QUATERNARY Qa Sand, clay, calcrete and lacustrine limestone in inland palaeodrainage; GEOLOGICAL MAP of the NORTHERN TERRITORY TERTIARY Cz fluvial sandstone and siltstone on Bathurst and Melville Islands 70 MONEY SHOAL, BONAPARTE, ARAFURA AND PEDIRKA AND EROMANGA 132°E 135°E CARPENTARIA BASINS BASINS 129°E 138°E Mudstone, Shale, shale sandstone K K CRETACEOUS 100 JUNCTION BAY MELVILLE ISLAND COBOURG PENINSULA WESSEL ISLANDS TRUANT ISLAND BATHURST ISLAND Minjilang Sandstone, Shale, shale, * Units not exposed sandstone MELVILLE * Jk mudstone * Jk ISLAND Johnston CAPE DON WESSEL ISLANDS JURASSIC Sandstone, Sandstone, Pirlangimpi Qa shale, shale Qa ARAFURA SEA * J coal * J Milikapiti Tjipripu River Murenella 200 TIMOR K Sandstone, Sandstone, River K Qa TRIASSIC shale, shale, Cz Warruwi * T limestone * T coal Cz Paru Pickertaramoor M10 Nguiu Qa Creek K SEA K Sandstone, Sandstone, Murgenella River PERMIAN limestone, shale, BATHURST VAN DIEMEN GULF P shale, coal, AMADEUS, NGALIA, DALY, P coal ISLAND King diamictite GEORGINA AND WISO BASINS Sandstone, Sandstone, 300 ALLIGATOR RIVER Coopers MILINGIMBI K Qa ARNHEM BAY 12°S DARWIN g4 M10 Galiwinku GOVE 12°S conglomerate, conglomerate, FOG BAY K K Maningrida siltstone, Pn Creek Milingimbi d9 M9 M8 CARBONIFEROUS siltstone, g4 C shale ALICE SPRINGS OROGENY 400-300 BEAGLE Nhulunbuy * DC shale, ADELAIDE K Qa Qa M6 coal, Qa d6 M10 Qa Qa Cato diamictite River Yirrkala GULF Qa g4 SOUTH ALLIGATOR Woolen g6 Sandstone, Qa River Ramingining K f6 g5 Wildman Oenpelli -

Hugh Young Inspected and Took Delivery of the Sheep on Victoria River Downs on January 20Th 1894

Hugh Young inspected and took delivery of the sheep on Victoria River Downs on January 20th 1894. Gunn then returned to Darwin while Young stayed on to take the sheep overland to Bradshaw.75 Five white men took charge of the sheep and by February or March 1894 the last of them had left VRD. Today one of the few visible signs that there ever were sheep on VRD is a set of rock paintings of sheep in the Stokes Range, on the northern boundary of the station (plate 111 ). From VRD the sheep were first taken to Delamere where about a dozen died from poisoning on the headwaters of Gregory Creek. 76 The sheep had been shorn some time before they arrived on the Gregory (probably while they were still on VRD where men to shear the sheep were available) and the wool was carted to the Depot by James Mulligan.77 From there it was taken by boat to the Dome where it was loaded on Bradshaw's 'steamerette', the 'Red Gauntlet', and shipped to Darwin.78 Probably because of the poisonings that had occurred it was decided that the route to Bradshaw via Gregory Creek was impassable for sheep; they were instead taken the long way around via Delamere, the Flora River and across to the headwaters of the Fitzmaurice River.79 By August 1894, Young had formed a sheep station on the 'open tableland' of the Upper Fitzmaurice, but had 'considerable trouble with the blacks,80 who on at least one occasion attacked the camp. No one was injured, but one man received a spear through his 75 J. -

GEOLOGICAL MAP of the NORTHERN TERRITORY TERTIARY Cz Fluvial Sandstone and Siltstone on Bathurst and Melville Islands

Ma Sand, silt and clay in coastal esturies 0 QUARTERNARY Qa Sand, clay, calcrete and lucastrine limestone in inland palaeodrainage; GEOLOGICAL MAP of the NORTHERN TERRITORY TERTIARY Cz fluvial sandstone and siltstone on Bathurst and Melville Islands 70 MONEY SHOAL, BONAPARTE, ARAFURA AND PEDIRKA AND EROMANGA 132°E 135°E CARPENTARIA BASINS BASINS 129°E 138°E Mudstone, Shale, shale sandstone K K CRETACEOUS 100 JUNCTION BAY MELVILLE ISLAND COBOURG PENINSULA WESSEL ISLANDS TRUANT ISLAND BATHURST ISLAND Minjilang Sandstone, Shale, shale, * Units not exposed sandstone MELVILLE * Jk mudstone * Jk ISLAND Johnston CAPE DON WESSEL ISLANDS JURASSIC Sandstone, Sandstone, Milikapiti Qa shale, shale Qa ARAFURA SEA * J coal * J Pularumpi Tjipripu River Murenella 200 TIMOR K Sandstone, Sandstone, River K Qa TRIASSIC shale, shale, Cz Warruwi * T limestone * T coal Cz Paru Pickertaramoor M10 Nguiu Qa Creek K SEA K Sandstone, Sandstone, Murgenella River PERMIAN limestone, shale, BATHURST VAN DIEMEN GULF P shale, coal, AMADEUS, NGALIA, DALY, P coal ISLAND King Galiwinku diamictite GEORGINA AND WISO BASINS Sandstone, Sandstone, 300 ALLIGATOR RIVER Coopers MILINGIMBI K Qa ARNHEM BAY 12°S DARWIN g4 M10 GOVE 12°S conglomerate, conglomerate, FOG BAY K K Maningrida siltstone, Pn Creek Milingimbi d9 M9 M8 CARBONIFEROUS siltstone, g4 C shale ALICE SPRINGS OROGENY 400-300 BEAGLE * DC shale, ADELAIDE K Qa M10 Qa M6 Nhulunbuy coal, Qa d6 Qa Qa Cato Yirrkala diamictite GULF Qa River g4 SOUTH ALLIGATOR Woolen g6 Sandstone, Qa Oenpelli River K f6 g5 DARWIN Wildman Ramingining -

Australian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts?

Preprint: Submitted to Archaeoastronomy – The Journal of Astronomy in Culture Australian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts? Duane W. Hamacher1 and Ray P. Norris2 Abstract Descriptions of cosmic impacts and meteorite falls are found throughout Australian Aboriginal oral traditions. In some cases, these texts describe the impact event in detail, suggesting that the events were witnessed, sometimes citing the location. We explore whether cosmic impacts and meteorite falls may have been witnessed by Aboriginal Australians and incorporated into their oral traditions. We discuss the complications and bias in recording and analysing oral texts but suggest that these texts may be used both to locate new impact structures or meteorites and model observed impact events. We find that, while detailed Aboriginal descriptions of cosmic impacts and meteorite falls are abundant in the literature, there is currently no physical evidence connecting any of these accounts to impact events currently known to Western science. Notice to Aboriginal Readers This paper gives the names of, or references to, Aboriginal people that have passed away throughout, and to information that may be considered sacred to some groups. It also contains information published in Nomads of the Australian Desert by Charles P. Mountford (1976). This book was banned from sale in the Northern Territory in 1976 as it contained sacred/secret knowledge of the Pitjantjatjara (see Brown 2004:33-35; Neate 1982). No information about the Pitjantjatjara from Mountford’s book is presented in this paper. 1 Department of Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, NSW, 2109, Australia [email protected] | Office: (+61) 2 9850 8671 Duane Hamacher is a PhD candidate in the Department of Indigenous Studies at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. -

Survey of the Barkly Region, Northern Territory and Queensland, 1947-48

IMPORTANT NOTICE © Copyright Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (‘CSIRO’) Australia. All rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO Division of Land and Water. The data, results and analyses contained in this publication are based on a number of technical, circumstantial or otherwise specified assumptions and parameters. The user must make its own assessment of the suitability for its use of the information or material contained in or generated from the publication. To the extend permitted by law, CSIRO excludes all liability to any person or organisation for expenses, losses, liability and costs arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in whole or in part) and any information or material contained in it. The publication must not be used as a means of endorsement without the prior written consent of CSIRO. NOTE This report and accompanying maps are scanned and some detail may be illegible or lost. Before acting on this information, readers are strongly advised to ensure that numerals, percentages and details are correct. This digital document is provided as information by the Department of Natural Resources and Water under agreement with CSIRO Division of Land and Water and remains their property. All enquiries regarding the content of this document should be referred to CSIRO Division of Land and Water. The Department of Natural Resources and Water nor its officers or staff accepts any responsibility for any loss or damage that may result in any inaccuracy or omission in the information contained herein. -

The Coming of the White People: a Broken Trust

Chapter One The coming of the white people: a broken trust …the past is never fully gone. It is absorbed into the present and the future. The present plight, in terms of health, employment, education, living conditions and self-esteem, of so many Aborigines must be acknowledged as largely flowing from what happened in the past [...] the new diseases, the alcohol and the new pressures of living were all introduced. Sir William Deane, Governor-General, Inaugural Lingiari Lecture, 1996.(Lingiari and Deane 1996:p20) Introduction This chapter will examine the history of the past two hundred plus years for indicators from which determinants of the poor health Aboriginal peoples experience today will be summarised. It will take the reader on a journey through time. Although the selection of events is a subjective one, it will allow the reader to consider the nature of the impacts of invasion on Aboriginal peoples. There are three core facts that constitute the common experience of Australia’s First Peoples. • They were invaded. • They were dispersed from their land. • They endured indescribable suffering in the wake of introduced disease. A discussion of these three factors opens this chapter in the context of the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. It must be remembered that the arrival of Europeans resulted in similar consequences throughout the entire country. In the first place, however, it is imperative for Settler or Migrant Australians to begin to understand the enduring relationship between Land and Aboriginal peoples, the interrelatedness of the people themselves, and in turn, the importance of these relationships to wellness relationships that will be further discussed later in this work.