Tennant Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

Kimberley Itinerary (Travelwise Can Organise Your Flight from Any State

Kimberley Itinerary (Travelwise can organise your flight from any state to join this tour) Day 1 – Saturday 04th June 06.30am – Depart Boomerang Beach 06.50am – Depart Forster Keys 07.00am – Depart Golden Ponds 07.05am – Depart Southern Parkway & Akala 07.15am – Depart Pacific Smiles 07.25am – Depart Club Forster 07.35am – Depart Tuncurry Beach St Bus Shelter 07.40am – Depart Chapmans Rd Tuncurry 08.10am – Depart Taree South Service Centre 08.30am – Depart Club Taree 08.45am – Depart Caravilla Motel Taree 09.00am – Depart Taree Airport 09.50am – Arrive Port Doughnut (comfort stop) 10.00am – Depart Port Doughnut 01.10pm – Arrive Walcha (lunch at own leisure) 02.00pm – Depart Walcha 05.30pm – Arrive Burk & Wills Motor Inn, Moree NSW 07.00pm – Dinner Day 2 – Sunday 05th June 07.00am – Breakfast 08.30am – Depart Moree 11.15am – Arrive Saint George QLD (lunch at own leisure) 12.10pm – Depart Saint George 05.45pm – Arrive Tambo Mill Motel, Tambo QLD Enjoy the slower pace and all the history that the oldest town in Outback Queensland has to offer (including town chicken races). 07.00pm – Dinner Provided (Carrangarra Hotel) Day 3 – Monday 06th June 07.00am – Breakfast Provided (Fanny Mae’s) 08.00pm – Depart Tambo 10.00am – Arrive Lara Station wetlands (morning tea provided) 10.30am – Depart Lara Station 12.00pm – Arrive Qantas Founders Museum Longreach (tour & lunch provided) Qantas Founders Museum is an award winning, world-class museum and cultural display, eloquently telling the story of Qantas through interpretive displays, interactive exhibits, original and replica aircraft and an impressive collection of genuine artifacts. -

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

Aboriginal and Indigenous Languages; a Language Other Than English for All; and Equitable and Widespread Language Services

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 819 FL 021 087 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph TITLE The National Policy on Languages, December 1987-March 1990. Report to the Minister for Employment, Education and Training. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 152p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advisory Committees; Agency Role; *Educational Policy; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Role; *National Programs; Program Evaluation; Program Implementation; *Public Policy; *Second Languages IDENTIFIERS *Australia ABSTRACT The report proviCes a detailed overview of implementation of the first stage of Australia's National Policy on Languages (NPL), evaluates the effectiveness of NPL programs, presents a case for NPL extension to a second term, and identifies directions and priorities for NPL program activity until the end of 1994-95. It is argued that the NPL is an essential element in the Australian government's commitment to economic growth, social justice, quality of life, and a constructive international role. Four principles frame the policy: English for all residents; support for Aboriginal and indigenous languages; a language other than English for all; and equitable and widespread language services. The report presents background information on development of the NPL, describes component programs, outlines the role of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME) in this and other areas of effort, reviews and evaluates NPL programs, and discusses directions and priorities for the future, including recommendations for development in each of the four principle areas. Additional notes on funding and activities of component programs and AACLAME and responses by state and commonwealth agencies with an interest in language policy issues to the report's recommendations are appended. -

Outback Safari

Outback Safari Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 classroom” at the School of the Air. Tour the school with a Local Specialist, see the Welcome to Uluru teachers in action, and learn how they were the first to use two-way radio broadcasts to educate remote students, providing support to children living in Hello, explorers! Surrounded by rusty earth and brilliant blue skies, you’re right in the surrounding isolated communities. After an insightful morning, get out and the heart of Australia to begin your Outback safari tour in the heart of the Red adventure in Karlu Karlu (Devils Marbles), an amazing outcrop of precariously Centre in World Heritage listed Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, a MAKE TRAVEL balanced granite boulders. These massive rocks of up to six metres high, believed MATTER® Experience. (Flights to arrive prior to 3pm). After meeting your Travel by the Warmungu Aboriginal people to be the fossilised eggs of the Rainbow Director and new travelling companions, you’ll head out for your first visit through Serpent, continue to crack and change shape even today. Walk among them the desert landscapes and iconic, rusty red home of Uluru. Over a sundowner of experiencing their majesty before reaching your home for the night in the former appetizers and sparkling wine, sit back as the surrounding grasses blow and the 1930s gold-mining town of Tennant Creek, “the Territory’s heart of gold.” Enjoy sky lights up in red and orange illuminating 'The Rock’ rising 348 metres high. -

Ali Curung CDEP

The role of Community Development Employment Projects in rural and remote communities: Support document JOSIE MISKO This document was produced by the author(s) based on their research for the report, The role of Community Development Employment Projects in rural and remote communities, and is an added resource for further information. The report is available on NCVER’s website: <http://www.ncver.edu.au> The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NCVER. Any errors and omissions are the responsibility of the author(s). SUPPORT DOCUMENT e Need more information on vocational education and training? Visit NCVER’s website <http://www.ncver.edu.au> 4 Access the latest research and statistics 4 Download reports in full or in summary 4 Purchase hard copy reports 4 Search VOCED—a free international VET research database 4 Catch the latest news on releases and events 4 Access links to related sites Contents Contents 3 Regional Council – Roma 4 Regional Council – Tennant Creek 7 Ali Curung CDEP 9 Bidjara-Charleville CDEP 16 Cherbourg CDEP 21 Elliot CDEP 25 Julalikari CDEP 30 Julalikari-Buramana CDEP 33 Kamilaroi – St George CDEP 38 Papulu Apparr-Kari CDEP 42 Toowoomba CDEP 47 Thangkenharenge – Barrow Creek CDEP 51 Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (2002) 53 Institute of Aboriginal Development 57 Julalikari RTO 59 NCVER 3 Regional Council – Roma Regional needs Members of the regional council agreed that the Indigenous communities in the region required people to acquire all the skills and knowledge that people in mainstream communities required. -

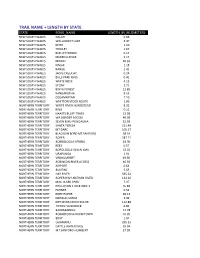

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

Annual Report 2017/18

East Arnhem Regional Council ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 01. Introduction President’s Welcome 6 02. East Arnhem Profile Location 12 Demographics 15 National & NT Average Comparison 17 Wards 23 03. Organisation CEO’s Message 34 Our Vision 37 Our Mission 38 Our Values 39 East Arnhem Regional Council 40 Executive Team 42 04. Statutory Reporting Goal 1: Governance 48 Angurugu 52 Umbakumba 54 Goal 2: Organisation 55 Milyakburra 58 Ramingining 60 Milingimbi 62 Goal 3: Built & Natural Environment 63 Galiwin’ku 67 Yirrkala 70 Gunyangara 72 Goal 4: Community & Economy 73 Gapuwiyak 78 05. Council Council Meetings Attendance 88 Finance Committee 90 WARNING: Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this publication may contain images Audit Committee 92 and names of people who have since passed away. Council Committees, Working Groups & Representatives 94 Elected Member Allowances 96 2 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 3 INTRODUCTION 4 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 East Arnhem Regional Council | Annual Report 2017/2018 5 Presidents Welcome On behalf of my fellow Council Members, I am pleased to In February 2018 our Local Authorities were spilled and new opportunities desperately needed. It is also important that I working together, to support and strengthen our people and present to you the East Arnhem Regional Council 2017 - 2018 nominations called. I’d like to acknowledge the outgoing Local recognise and thank the staff of the Department of Housing opportunities. Acting Chief Executive Officer Barry Bonthuys Annual Report, the tenth developed by Council. -

Fixing the Hole in Australia's Heartland

Fixing the hole in Australia’s Heartland: How Government needs to work in remote Australia September 2012 Dr Bruce W Walker Dr Douglas J Porter Professor Ian Marsh The remoteFOCUS project is an initiative facilitated by Desert Knowledge Australia. Support to make this report possible has been provided by: Citation: Walker BW, Porter DJ, and Marsh I. 2012 Fixing the Hole in Australia’s Heartland: How Government needs to work in remote Australia, Desert Knowledge Australia, Alice Springs ISBN: 978-0-9873958-2-5 This report has been authored by: ISBN Online: 978-0-9873958-3-2 Dr Bruce W Walker, remoteFOCUS Project Director Dr Douglas J Porter, Governance Adviser, World Bank, Associated Reports: & Adjunct Professor, International Politics and Security Walker, BW, Edmunds, M and Marsh, I. 2012 Loyalty for Studies, Australian National University Regions: Governance Reform in the Pilbara, report to the Pilbara Development Commission, Desert Knowledge Australia Professor Ian Marsh, Adjunct Professor, Australian ISBN: 978-0-9873958-0-1 Innovation Research Centre, University of Tasmania Walker, BW, (Ed) Edmunds, M and Marsh, I. 2012 The With contributions by: remoteFOCUS Compendium: The Challenge, Conversation, Dr Mary Edmunds Commissioned Papers and Regional Studies of Remote Australia, Mr Simon Balderstone AM Desert Knowledge Australia. ISBN: 978-0-9873958-1-8 And review by the remoteFOCUS Reference Group: Copyright: Desert Knowledge Australia 2012 Hon Fred Chaney AO (Convenor) Licensed under the Creative Commons Dr Peter Shergold AC Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike Licence Mr Neil Westbury PSM For additional information please contact: Mr Bill Gray AM Dr Bruce Walker Mr John Huigen (CEO Desert Knowledge Australia) Project Director | remoteFOCUS M: 0418 812 119 P: 08 8959 6125 The views expressed here are those of the individuals E: [email protected] and the remoteFOCUS team and should not be taken as W: www.desertknowledge.com.au/Our-Programs/remoteFOCUS representing the views of their employers. -

Show 2.0 Is Coming to Tennant MAYOR Jeffrey Mclaughlin Said He’S Proud to Announce “Show 2.0” and District Show Society

ENNANT & DISTRICT TIMES SAY NO MORE TO www.tdtimes.com.au | Phone (08) 8962 1040 | Email [email protected] FAMILY VIOLENCE Vol. 45 No. 29 FRIDAY 30 JULY 2021 FREE Nyinkka Nyunyu hosts NAIDOC Week finale o By CATHERINE GRIMLEY TENNANT Creek’s NAIDOC festivities ended on a high note on Saturday with a community gathering at Nyinkka Nyunyu. Tjupi Band played their hearts out for the crowd, even being joined on stage by Mayor Jeffrey McLaughlin, who got a reminder of how long it has been since he played hand drums, and what muscles he needs to use to play them. The bacon and egg sandwiches and coffee were popular, but café workers and volunteers kept the lines moving quickly. With the jumping castle, face painting and even a visit from Donald Duck the kids were able to have a barrel of fun while the adults enjoyed the live music. A great finale to a week of activities that the NAIDOC Committee should be proud of. Turn to pages 10-11 for more photo coverage. Show 2.0 is coming to Tennant MAYOR Jeffrey McLaughlin said he’s proud to announce “Show 2.0” and District Show Society. is coming to Tennant Creek next weekend. “After COVID-19 reached Central Australia and the restrictions hit causing The Show with a difference will include a Sideshow Alley next Friday 6 us to miss out on the annual show, there was a team working to bring it back August. to the Barkly,” he said. Barkly Regional Arts’ annual Desert Harmony Festival, which kicked off “It shows the resilience of the town that was crying out for something to yesterday, will hold the Barkly Area Music Festival (BAMFest) on Saturday celebrate in these troubled times. -

Aeromagnetic Data Acquisition by Geoscience Australia & States

AEROMAGNETIC DATA ACQUISITION BY GEOSCIENCE AUSTRALIA & STATES 120°E 126°E 132°E 138°E 144°E 150°E 8°S 8°S BOIGU DARU MAER TORRES STRAIT COBOURG PENINSULA JUNCTION BAY BATHURST ISLAND MELVILLE ISLAND WESSEL ISLANDS TRUANT ISLAND JARDINE RIVER ORFORD BAY ALLIGATOR RIVER MILINGIMBI FOG BAY DARWIN ARNHEM BAY GOVE WEIPA CAPE WEYMOUTH MOUNT EVELYN MOUNT MARUMBA CAPE SCOTT PINE CREEK BLUE MUD BAY PORT LANGDON 12°S LONDONDERRY AURUKUN 12°S COEN FERGUSSON RIVER KATHERINE URAPUNGA ROPER RIVER CAPE BEATRICE MEDUSA BANKS PORT KEATS DRYSDALE HOLROYD MONTAGUE SOUND EBAGOOLA BROWSE ISLAND CAPE MELVILLE DELAMERE LARRIMAH HODGSON DOWNS MOUNT YOUNG PELLEW CAMBRIDGE GULF AUVERGNE ASHTON RUTLAND PLAINS PRINCE REGENT HANN RIVER CAMDEN SOUND COOKTOWN DALY WATERS TANUMBIRINI BAUHINIA DOWNS WATERLOO VICTORIA RIVER DOWNS ROBINSON RIVER MORNINGTON LISSADELL CAPE VAN DIEMEN MOUNT ELIZABETH GALBRAITH CHARNLEY WALSH YAMPI MOSSMAN PENDER CAIRNS BEETALOO LIMBUNYA WAVE HILL NEWCASTLE WATERS WALHALLOW CALVERT HILLS DIXON RANGE WESTMORELAND BURKETOWN LANSDOWNE NORMANTON 16°S 16°S LENNARD RIVER RED RIVER DERBY ATHERTON BROOME INNISFAIL SOUTH LAKE WOODS HELEN SPRINGS BRUNETTE DOWNS BIRRINDUDU WINNECKE CREEK MOUNT DRUMMOND LAWN HILL GORDON DOWNS DONORS HILL MOUNT RAMSAY CROYDON NOONKANBAH GEORGETOWN MOUNT ANDERSON EINASLEIGH LAGRANGE INGHAM TENNANT CREEK TANAMI TANAMI EAST GREEN SWAMP WELL ALROY RANKEN BILLILUNA CAMOOWEAL DOBBYN MOUNT BANNERMAN MILLUNGERA CROSSLAND GILBERTON MCLARTY HILLS CLARKE RIVER MUNRO TOWNSVILLE MANDORA AYR BEDOUT ISLAND BONNEY WELL THE GRANITES MOUNT -

(LGANT) Annual General Meeting Has Elected a New Leadership Team for the Next Two Years That Includes

View this email in your browser The Local Government Association of the Northern Territory (LGANT) Annual General Meeting has elected a new leadership team for the next two years that includes: President Lord Mayor Kon Vatskalis City of Darwin Vice-President Municipal Vice-President Regional Councillor Kirsty Sayers-Hunt Councillor Peter Clee Litchfield Council Wagait Shire Council Executive Members Councillor Kris Civitarese Barkly Regional Council Deputy Mayor Peter Gazey Katherine Town Council Mayor Judy MacFarlane Roper Gulf Regional Council Councillor Georgina Macleod Victoria Daly Regional Council Deputy Mayor Peter Pangquee City of Darwin Councillor Bobby Wunungmurra East Arnhem Regional Council The LGANT Secretariat looks very much forward to working with the new President. He has a track record of getting things done, is an expert negotiator with an extensive network within the Territory and across Australia and will have a focus on equity, fairness, and good governance. There are six first-timers on the Executive drawn from all parts of the Territory, all bringing a unique set of skills and experience, with Mayor MacFarlane, Deputy Mayor Pangquee and Councillor Wunungmurra re- elected from the previous Board. The LGANT Executive will meet every month and has on its agenda advocacy on issues such as water security, housing, climate change adaptation, cyclone shelters, connectivity, infrastructure funding and working with the Territory and Commonwealth governments, councils, land councils and communities to assist in the progression of closing the gap targets. The election in Alice Springs marked the end of the tenure of Mayor Damien Ryan as President after ten years on the Executive and eight of those as President.