Ross (1915 – 1999)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

Than One Way to Catch a Frog: a Study of Children's

More than one way to catch a frog: A study of children’s discourse in an Australian contact language Samantha Disbray Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics University of Melbourne December, 2008 Declaration This is to certify that: a. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD b. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all material used c. the text is less than 100,000 words, exclusive of tables, figures, maps, examples, appendices and bibliography ____________________________ Samantha Disbray Abstract Children everywhere learn to tell stories. One important aspect of story telling is the way characters are introduced and then moved through the story. Telling a story to a naïve listener places varied demands on a speaker. As the story plot develops, the speaker must set and re-set these parameters for referring to characters, as well as the temporal and spatial parameters of the story. To these cognitive and linguistic tasks is the added social and pragmatic task of monitoring the knowledge and attention states of their listener. The speaker must ensure that the listener can identify the characters, and so must anticipate their listener’s knowledge and on-going mental image of the story. How speakers do this depends on cultural conventions and on the resources of the language(s) they speak. For the child speaker the development narrative competence involves an integration, on-line, of a number of skills, some of which are not fully established until the later childhood years. -

A Twentieth-Century Aboriginal Family

Chapter 10 The Northern Territory, 1972 The 1972 Federal election was a time of heightened tension among interest groups in Australia. The Liberal-Country Party coalition had been in power since 1949 and all politically minded people sensed a change. All except those in power. Aboriginal poverty, high infant mortality rates and the question of Land Rights left Aboriginal leaders wondering how they could contribute in the political milieu they were confronted with. Charlie Perkins had been telling me for three or four years that he wanted to ‘get rid of this government’, in particular to show his contempt for the Country Party. Charlie at the time was an Assistant Secretary in the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and in spite of his role as a bureaucrat he was intimately involved in Aboriginal politics. So was I. On many occasions he would express his confidence that change in Aboriginal people’s living conditions were just around the corner while at other times he would be filled with despair. The time frame between accepting the nomination to run for the Northern Territory seat and leaving Sydney was very tight. As a family we had to sell the Summer Hill house to finance getting to, and living in Alice Springs. I had to resign from the Legal Service, make contact with the Australia Party base in Darwin and prepare my thinking for an election campaign. One of the first things I did was to speak to my colleague Len Smith to seek his views about if, and how, I should run my campaign. -

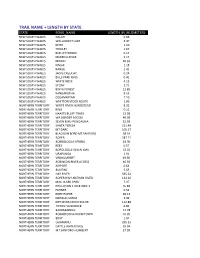

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

Contents What’S New

July / August, No. 4/2011 CONTENTS WHAT’S NEW Quandamooka Native Title Determination ............................... 2 Win a free registration to the Joint Management Workshop at the 2011 National Native 2012 Native Title Conference! Title Conference: ‘What helps? What harms?’ ........................ 4 Just take 5 minutes to complete our An extract from Mabo in the Courts: Islander Tradition to publications survey and you will go into the Native Title: A Memoir ............................................................... 5 draw to win a free registration to the 2012 QLD Regional PBC Meeting ...................................................... 6 Native Title Conference. Those who have What’s New ................................................................................. 6 already completed the survey will be automatically included. Recent Cases ............................................................................. 6 Legislation and Policy ............................................................. 12 Complete the survey at: Native Title Publications ......................................................... 13 http://www.tfaforms.com/208207 Native Title in the News ........................................................... 14 If you have any questions or concerns, please Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) ........................... 20 contact Matt O’Rourke at the Native Title Research Unit on (02) 6246 1158 or Determinations ......................................................................... 21 [email protected] -

MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: Research Material and Indexes, 1964-1968

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY………………………………………….......page 5 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT……………………………..page 5 ACCESS TO COLLECTION………………………………………….…page 6 COLLECTION OVERVIEW……………………………………………..page 7 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………...………………page 10 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………...page 12 Series 1 Research material files Folder 1/1 Abstracts Folder 1/2 Agriculture, c.1963-1964 Folder 1/3 Arts, 1936-1965 Folder 1/4 Attitudes, c.1919-1967 Folder 1/5 Bibliographies, c.1960s MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 Folder 1/6 Case Histories, c.1934-1966 Folder 1/7 Cooperatives, c.1954-1965. Folder 1/8 Councils, 1961-1966 Folder 1/9 Courts, Folio A-U, 1-20, 1907-1966 Folder 1/10-11 Civic Rights, Files 1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/12 Crime, 1964-1967 Folder 1/13 Customs – Native, 1931-1965 Folder 1/14 Demography – Census 1961 – Australia – full-blood Aboriginals Folder 1/15 Demography, 1931-1966 Folder 1/16 Discrimination, 1921-1967 Folder 1/17 Discrimination – Freedom Ride: press cuttings, Feb-Jun 1965 Folder 1/18-19 Economy, Pts.1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/20-21 Education, Files 1 & 2, 1936-1967 Folder 1/22 Employment, 1924-1967 Folder 1/23 Family, 1965-1966 -

Aeromagnetic Data Acquisition by Geoscience Australia & States

AEROMAGNETIC DATA ACQUISITION BY GEOSCIENCE AUSTRALIA & STATES 120°E 126°E 132°E 138°E 144°E 150°E 8°S 8°S BOIGU DARU MAER TORRES STRAIT COBOURG PENINSULA JUNCTION BAY BATHURST ISLAND MELVILLE ISLAND WESSEL ISLANDS TRUANT ISLAND JARDINE RIVER ORFORD BAY ALLIGATOR RIVER MILINGIMBI FOG BAY DARWIN ARNHEM BAY GOVE WEIPA CAPE WEYMOUTH MOUNT EVELYN MOUNT MARUMBA CAPE SCOTT PINE CREEK BLUE MUD BAY PORT LANGDON 12°S LONDONDERRY AURUKUN 12°S COEN FERGUSSON RIVER KATHERINE URAPUNGA ROPER RIVER CAPE BEATRICE MEDUSA BANKS PORT KEATS DRYSDALE HOLROYD MONTAGUE SOUND EBAGOOLA BROWSE ISLAND CAPE MELVILLE DELAMERE LARRIMAH HODGSON DOWNS MOUNT YOUNG PELLEW CAMBRIDGE GULF AUVERGNE ASHTON RUTLAND PLAINS PRINCE REGENT HANN RIVER CAMDEN SOUND COOKTOWN DALY WATERS TANUMBIRINI BAUHINIA DOWNS WATERLOO VICTORIA RIVER DOWNS ROBINSON RIVER MORNINGTON LISSADELL CAPE VAN DIEMEN MOUNT ELIZABETH GALBRAITH CHARNLEY WALSH YAMPI MOSSMAN PENDER CAIRNS BEETALOO LIMBUNYA WAVE HILL NEWCASTLE WATERS WALHALLOW CALVERT HILLS DIXON RANGE WESTMORELAND BURKETOWN LANSDOWNE NORMANTON 16°S 16°S LENNARD RIVER RED RIVER DERBY ATHERTON BROOME INNISFAIL SOUTH LAKE WOODS HELEN SPRINGS BRUNETTE DOWNS BIRRINDUDU WINNECKE CREEK MOUNT DRUMMOND LAWN HILL GORDON DOWNS DONORS HILL MOUNT RAMSAY CROYDON NOONKANBAH GEORGETOWN MOUNT ANDERSON EINASLEIGH LAGRANGE INGHAM TENNANT CREEK TANAMI TANAMI EAST GREEN SWAMP WELL ALROY RANKEN BILLILUNA CAMOOWEAL DOBBYN MOUNT BANNERMAN MILLUNGERA CROSSLAND GILBERTON MCLARTY HILLS CLARKE RIVER MUNRO TOWNSVILLE MANDORA AYR BEDOUT ISLAND BONNEY WELL THE GRANITES MOUNT -

50 Seniors 50 Stories – Digital Edition

5050 stories.seniors. 5050 stories.seniors. Acknowledgements Firstly, COTA NT would like to acknowledge and thank all the story tellers we spoke with for sharing an insight into what the Territory means to them. We hope you enjoyed telling your stories as much as we have enjoyed reading them. We would also like to thank members of our Board, staff and volunteer team for sharing their stories too – we have a very diverse and inspiring family! And we thank those who gave their time to collect the stories, especially Fran Smith for her professionalism, hard work and dedication to the project. Supported by the Northern Territory Government through the Northern Territory History Grants Program of the Department of Tourism, Sport and Culture. Copyright 2019 © Council on the Ageing (Northern Territory) Inc. Also known as COTA NT Foreword COTA NT wanted to mark 50 years of operations in the Northern Territory by celebrating some of the seniors it works to support. We could not think of a better way to do it than to collect 50 stories from our seniors throughout the Northern Territory and share them with you. “50 Seniors, 50 Stories” offers an insight into NT seniors’ lives: their thoughts, their histories and how they enjoy the lifestyle of the Territory. I found reading the stories enthralling and I know you will too. We have many more stories to share – so we might even produce a second edition! We tried to gather stories from every region, but realised that most of our storytellers had lived in many parts of the Territory, and experienced each region's unique landscape and hospitality. -

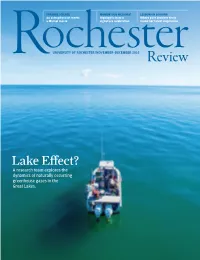

Lake E≠Ect? a Research Team Explores the Dynamics of Naturally Occurring Greenhouse Gases in the Great Lakes

STRANGE SCIENCE MOMENTOUS MELIORA! LESSONS IN LOOKING An astrophysicist meets Highlights from a Where poet Jennifer Grotz a Marvel movie signature celebration found her latest inspiration UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER /NovembER–DecembER 2016 Lake E≠ect? A research team explores the dynamics of naturally occurring greenhouse gases in the Great Lakes. RochRev_Nov2016_Cover.indd 1 11/1/16 4:38 PM “You have to feel strongly about where you give. I really feel I owe the University for a lot of my career. My experience was due in part Invest in PAYING IT to someone else’s generosity. Through the George Eastman Circle, I can help students what you love with fewer resources pursue their career “WE’RE BOOMERS. We think we’ll be aspirations at Rochester.” around forever—but finalizing our estate FORWARD gifts felt good,” said Judy Ricker. Her husband, —Virgil Joseph ’01 | Vice President-Relationship Manager, Ray, agrees. “It’s a win-win for us and the Canandaigua National Bank & Trust University,” he said. “We can provide for FOR FUTURE Rochester, New York ourselves in retirement, then our daughter, Member, George Eastman Circle Rochester Leadership Council and the school we both love.” GENERATIONS Supports: School of Arts and Sciences The Rickers’ charitable remainder unitrust provides income for their family before creating three named funds at the Eastman School of Music. Those endowed funds— two professorships and one scholarship— will be around forever. They acknowledge Eastman’s celebrated history, and Ray and Judy’s confidence in the School’s future. Judy’s message to other boomers? “Get on this bus! Join us in ensuring the future of what you love most about the University.” Judith Ricker ’76E, ’81E (MM), ’91S (MBA) is a freelance oboist, a business consultant, and former executive vice president of brand research at Market Probe. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-01190-7

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-01190-7 - Native Title in Australia: An Ethnographic Perspective Peter Sutton Index More information Index Aboriginal Land Act 1991 (Queensland) 18, Burketown 5 133, 211 bush tucker 28 Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Commonwealth) xiv, xv, 10, 18, 86, Campbell, Lyle 163 107, 108–9, 147, 191 Cape Keerweer 75, 127, 130, 165 Aboriginal Law and laws xvi, 21, 22–3, 25–6, Cape Melville (case) 6, 211, 223 32–7, 112–16 Cape York Peninsula 2, 3, 17, 18, 51, 58, 59, agnates 198 61, 71, 73, 75, 79, 80, 107, 113, 123, 127, Alpher, Barry 163 133, 156, 164, 165 Altman, Jon 29 Central Australia 50 ambilineal descent 196–9 Central Land Council 86 Amunturrngu (Mount Liebig) people 61 Chase, Athol 227 ancestors 190 ‘clans’ 39–40, 41–2, 46, 49, 51, 99, 152, Anderson, Christopher 2, 58 155–6, 157 Antakirinya people 61 codification and native title 16, 18 anthropology cognatic descent groups 198, 208, 209, 210, and Aboriginal land tenure xviii, 38–9, 52, 212, 213, 214–15, 220–1, 226–31 53, 55, 57–9, 61–2, 80, 85–6, 87–8, 91, composition 219 137–8, 145–6, 178 stratification 224 and Aboriginal localism 90–2 structure 217–18 of Aboriginal regions 91, 92–4 surname groups 225–6 and land claims 85–6, 87–8 transformations in local organisations 222–4 and regional studies 91, 94–7 collective land rights 27–9 writing 171–2 ‘communities’, Aboriginal xix, 42, 67, 98–109 Arnhem Land 21, 50, 71, 72, 74, 75, 104, 116, complementary filiation 194–6 127, 149, 164 conjoint succession 6 Arrernte people 50, 91 contingent -

Department of Health Library Services Epublications - Historical Collection

Department of Health Library Services ePublications - Historical Collection Purpose To apply preservation treatments, including digitisation, to a high value and vulnerable Historical collection of items held in the Darwin and Alice Springs libraries so that the items may be accessed without causing further damage to the original items and provide accessibility for stakeholders. Reference and Research Disclaimer Please note: this document is part of the Historical Collection and the information contained within may be out of date. This copy is a reproduction of an original record. Please note that the quality of the original record may be poor and cannot be enhanced with the scanning process. Northern Territory Department of Health Library Services Historical Collection 0 0-7,::;_ 7 HISTORICAL COLLECTION ""€ NT DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH I -~ l ~ AND COMMUNITY SERVICES ·la..- j ~ .. ~ '~ .. ' .. • t. ;., :· .. : ,... ... '! ..- • ..._._.( .....' . :-. !. MEDICAL ENTOMOLOGY INVESTIGATION •' . {:~ OF PROPOSED JUNCTION WATER HOLE DAM ON THE TODD RIVER ""-. •'So ti : t i r• ..: I.• l • '• . ' "ii -' • ~ • I ' . ' ' ' I ( I • ~ • • ~ I I~ 't I!' ~. • • • ·1, J ~ • :. • .'.!. ', ,, . r • I •/, l ·~. • •..... "·,1 '). I .} ...1. .,' • : • I J l• ".• ·, it, ! ·•,, 1 f ~.. ; ...... ' . ,,._ For more Information Contact: ' '' I j,t 1· Department of Health and Community Services : 'I• Medical Entomology Branch GPO Box 1701 •I ' DARWIN NT 0801 • I Telephone 22 8333 Peter Whelan Senior Medical Entomologist , .. 'DLHIST 614.4323 .J WHE 'i 1990 ,.. I 1l1[1l1~11i1 ~lllf1111ij1i 1111]1i11~1111 ~1~1ij 111111~11 3 oa20 00019002 o 1':3~() MEDICAL ENTOMOLOGY INVESTIGATION OF PROPOSED JUNCTION WATERHOLE DAM ON THE TODD RIVER . PETER WHELAN SENIOR MEDICAL ENTOMOLCGIST MEDICAL ENTO'v10LCGY BRANCH NORTHERN TERRITORY DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND COMMUNITY SERVICES MARCH 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. -

Atomic Thunder: the Maralinga Story

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Members of the Editorial Board Maria Nugent (Chair), Tikka Wilson (Secretary), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Co-Editor), Liz Conor (Co-Editor), Luise Hercus (Review Editor), Annemarie McLaren (Associate Review Editor), Rani Kerin (Monograph Editor), Brian Egloff, Karen Fox, Sam Furphy, Niel Gunson, Geoff Hunt, Dave Johnston, Shino Konishi, Harold Koch, Ann McGrath, Ewen Maidment, Isabel McBryde, Peter Read, Julia Torpey, Lawrence Bamblett. Editors: Ingereth Macfarlane and Liz Conor; Book Review Editors: Luise Hercus and Annemarie McLaren; Copyeditor: Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.