European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020121926.Pdf

B.S.E,B B.S.E.B BEIEI VILL.OHANCHHUHAN, PS. DHARM VIJAY KUMAR JANESHWAR SHARMA 15-01-1993 79790013,15 329/500 93t/1500 t65/1300 CHAURI,OIST.. BHOJPUR 71..4591 BSEB BSEB, BTEI BADAUNI, PAKHALPIJR, 121a PARAS NAJH SHARMA 11-02-1994 821140A113 4123/6rOO 101/ta0 71.56 €7,G7% GEN 07-03-1991 71.52 BARI PATAN DEVI i/IANDIR PILI 127 2472 PRASANJEET PANOEY GANESH DUIT PANOEY GEN 01-011995 7903247065 XOTHI,PO.GUIZARBAGH 71.51 PArra l00oil7 VILL. SHATAULI JAITURNA, EP 124 TUFANI SINGH o2.ol-tre5 0017675037 71.61 oBc XAI'URIBHAAHUA) 421110 ,2.24% ts€B ltac OAYA SHAI{XER 12' 1231 PRABHAXER CHAUEEY GEN 0t.03.t077 7$6.13776.1 71.trt ChAUBEY 6.XA CBSE aaEa, CTET OURASIIAI{ PO'UUARI ti9t sc m 26{0-t0orr gUXAR t72t*o tTlr(to raa{loo a2l't& 71.50 a4.aata 72.00t6 ASEB AEIET /('l 924 VlsHVAflATH SINGH GEN 05{1-1,t5 anlaa32111 1033/13O0 BZ/119 71.4 BSGB ESEB CTET 432 711 GEN t6{9-tata !rta305 2037n1OO 53.6 73.A a5.7 tsEa 15EB CIEI 433 t6G ABHISHEK ANANO SHRIRA'II SINGTI EBC t 4-ot-tt97 70613/t7563 SATGHARVA ROHTAS 352/500 71,5 5a.l 62.14 1C.54 55 al.Ei. i.s.a.a. Ntos o?r U[. BIIVA.PoJAGDEHPUR AEHIS}IEK I(UMAR (ta a1e JAY GOPAI SHARMA ST 15.02.t807 &$la5670 BBOJAR 714 S}|ARI'A ,o2152 51.ilil96 --t AAHEHEK KUiIAR AT.BIWAN JAGDISHPUR -ss m@ ST tM2-ltt7 tr2o77tg30 gHG'PUR 71.4 V-' \ Page 36 of 209 W sc 05 03.1935 SHYAM NAGAR JAHANASAO MD AMANULLAH AMIR 22-02-1990 KAJITOLA ARA BHOJPUR 71.33 BC ST o5-05"t931 UDHPT'RA KASTIIARI XAIMUR 71,37 GUG, CBSE RU, NANC}iI BTET VILL+'OiAiATI HUHAINABAD 13!t GEN io{2.lrto t603570995 tt&aa(, a7tlltoo lor&r{,o 71,36 ,6.10l( 6t.f?x VBSPU. -

Page 20 Backup Bulletin Format on Going

gkfnL] nfsjftf] { tyf ;:s+ lt[ ;dfh Nepali Folklore Society Nepali Folklore Society Vol.1 December 2005 The NFS Newsletter In the first week of July 2005, the research Exploring the Gandharva group surveyed the necessary reference materials related to the Gandharvas and got the background Folklore and Folklife: At a information about this community. Besides, the project office conducted an orientation programme for the field Glance researchers before their departure to the field area. In Introduction the orientation, they were provided with the necessary technical skills for handling the equipments (like digital Under the Folklore and Folklife Study Project, we camera, video camera and the sound recording device). have completed the first 7 months of the first year. During They were also given the necessary guidelines regarding this period, intensive research works have been conducted the data collection methods and procedures. on two folk groups of Nepal: Gandharvas and Gopalis. In this connection, a brief report is presented here regarding the Field Work progress we have made as well as the achievements gained The field researchers worked for data collection in from the project in the attempt of exploring the folklore and and around Batulechaur village from the 2nd week of July folklife of the Gandharva community. The progress in the to the 1st week of October 2005 (3 months altogether). study of Gopalis will be disseminated in the next issue of The research team comprises 4 members: Prof. C.M. Newsletter. Bandhu (Team Coordinator, linguist), Mr. Kusumakar The topics that follow will highlight the progress and Neupane (folklorist), Ms. -

Annual Report 2073/74 (2016/17)

ANNUAL REPORT 2073/74 (2016/17) GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL NEPAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH COUNCIL NATIONAL CITRUS RESEARCH PROGRAMME PARIPATLE, DHANKUTA 2017 i © National Citrus Research Programme, Paripatle, Dhankuta, NARC, 2017 Nepal Agriculture Research Council (NARC) National Citrus Research Programme (NCRP) Paripatle, Dhankuta, Nepal Postal code: 56800, Dhankuta, Nepal Contact No.: 026-620232; 9852050752 (Cell phone) Email address: [email protected] URL: http://www.narc.gov.np Citation: NCRP, 2017. Annual report 2073/74 (2016/17). NARC Publication Serial No 00549- 362/2017/18, National Citrus Research Programme, Paripatle, Dhankuta, Nepal. ii FOREWORD Citrus production has a great potential in Nepalese mid-hills for economic enhancement as well as nutritional supplement among the hill farmers. Although, the production of mandarin and sweet orange has been localized in mid-hills, acid lime production has been widened in hills and terai plains. The released acid lime varieties viz., Sunkagati-1 and Sunkagati-2 are being popular and their saplings demand for commercial orchards have been ever increasing. National Citrus Research Programme (NCRP), Dhankuta has been working in coordination with other stakeholders to fulfill the demand of saplings, suitable varieties and technologies in the country. From this year onwards, NCRP has got a new responsibility to carry out research activities on Sweet Orange (junar) under Prime Minister Agriculture Modernization Project (PMAMP) in Sindhuli and Ramechhap districts. NCRP has to coordinate with Project Implementation Unit of Super Zone Office separately established for sweet orange by Ministry of Agriculture Development under the PMAMP in the respective districts. Despite the chronic shortage of researchers and technical staff, NCRP has been working in full capacity to perform the required research and development activities as mandated by the nation. -

Rakam Land Tenure in Nepal

13 SACRAMENT AS A CULTURAL TRAIT IN RAJVAMSHI COMMUNITY OF NEPAL Prof. Dr. Som Prasad Khatiwada Post Graduate Campus, Biratnagar [email protected] Abstract Rajvamshi is a local ethnic cultural group of eastern low land Nepal. Their traditional villages are scattered mainly in Morang and Jhapa districts. However, they reside in different provinces of West Bengal India also. They are said Rajvamshis as the children of royal family. Their ancestors used to rule in this region centering Kuchvihar of West Bengal in medieval period. They follow Hinduism. Therefore, their sacraments are related with Hindu social organization. They perform different kinds of sacraments. However, they practice more in three cycle of the life. They are naming, marriage and death ceremony. Naming sacrament is done at the sixth day of a child birth. In the same way marriage is another sacrament, which is done after the age of 14. Child marriage, widow marriage and remarriage are also accepted in the society. They perform death ceremony after the death of a person. This ceremony is also performed in the basis of Hindu system. Bengali Brahmin becomes the priests to perform death sacraments. Shradha and Tarpana is also done in the name of dead person in this community. Keywords: Maharaja, Thana, Chhati, Panju and Panbhat. Introduction Rajvamshi is a cultural group of people which reside in Jhapa and Morang districts of eastern Nepal. They were called Koch or Koche before being introduced by the name Rajvamshi. According to CBS data 2011, their total number is 115242 including 56411 males and 58831 females. However, the number of Rajvamshi Language speaking people is 122214, which is more than the total number this group. -

Journal of Asian Arts, Culture and Literature (Jaacl) Vol 2, No 1: March 2021

JOURNAL OF ASIAN ARTS, CULTURE AND LITERATURE (JAACL) VOL 2, NO 1: MARCH 2021 Riveting Nepal: A Cultural Flash! By Ms. Mahua Sen [email protected] Abstract “A Nepali outlook, pace and philosophy had prevented us being swamped by our problems. In Nepal, it was easier to take life day by day.” -Jane Wilson-Howarth, A Glimpse of Eternal Snows: A Journey of Love and Loss in the Himalayas. We do sniff the essence of Nepal in these lines! Squeezed in between China and India, Nepal is one of the most fascinating places to visit on earth. Home to the awe-inspiring Mt. Everest, the birthplace of Lord Buddha, this exquisite country stretches diverse landscapes from the Himalayan Mountains in the North to the flat expansive plains in the south. The birth of the nation is dated to Prithvi Narayan Shah's conquest of the Kathmandu Valley kingdoms in 1768. Deep gorges, sky-scraping mountains, exuberant culture and charismatic people – Nepal is the ideal destination not only for adventurers but also for people seeking a peaceful sojourn in the lap of serenity. Keywords Nepal, culture, festival, Hindu, Buddhism 1 JOURNAL OF ASIAN ARTS, CULTURE AND LITERATURE (JAACL) VOL 2, NO 1: MARCH 2021 Festival Flavors Customs and culture vary from one part of Nepal to another. The capital city Kathmandu is drenched in a rich drapery of cultures, a unique silhouette to form a national identity. Nepali culture portrays an amalgamation of Indo-Aryan and Tibeto-Mongolian influences, the result of a long history of migration, conquest, and trade. -

Cultural Perspective of Tourism in Nepal

Cultural Perspective of Tourism in Nepal Nepal, Shankar Baral, Nenshan 2015 Kerava Laurea University of Applied Sciences Kerava Cultural Perspective of Tourism in Nepal Shankar Nepal, Nenshan Baral Degree Programme in Tourism Bachelor’s Thesis February 2016 Laurea University of Applied Sciences Abstract Kerava Degree Programme in Tourism Shankar Nepal Nenshan Baral Cultural perspectives of Tourism in Nepal Year 2016 Pages 39 This Bachelor’s thesis is conducted with the main objective of understanding the perspective of culture and its impact on the tourism industry of the host country i.e. Nepal. Furthermore, it will help to gain insight about the possible opportunities and threats in tourism through the responses gathered from various respondents. To research the topic, a web-based survey was conducted among the Nepali youths (mostly students) belonging different places via social networking sites. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches have been applied in this thesis. To gain initial insight regarding culture and tourism, online material related to different cultural monu- ments and places of historical importance within and outside the Kathmandu Valley were re- ferred. This provided a basis for quantitative research conducted in the next phase of the re- search. For the purpose of the study, online questionnaires using Google forms were created and sent via various social networking platforms for responses. Before developing the questionnaires for the online survey, researcher thoroughly reviewed the literature and considered the main objectives. For study purposes, data published by Ne- pal Tourism Board and various research works from other researchers relating to the same field were also examined. The data thus collected are analyzed using various statistical methods. -

Madan Bhandari Highway

Report on Environmental, Social and Economic Impacts of Madan Bhandari Highway DECEMBER 17, 2019 NEFEJ Lalitpur Executive Summary The report of the eastern section of Madan Bhandari Highway was prepared on the basis of Hetauda-Sindhuli-Gaighat-Basaha-Chatara 371 km field study, discussion with the locals and the opinion of experts and reports. •During 2050's,Udaypur, Sindhuli and MakwanpurVillage Coordination Committee opened track and constructed 3 meters width road in their respective districts with an aim of linking inner Madhesh with their respective headquarters. In the background of the first Madhesh Movement, the road department started work on the concept of alternative roads. Initially, the double lane road was planned for an alternative highway of about 7 meters width. The construction of the four-lane highway under the plan of national pride began after the formation of a new government of the federal Nepal on the backdrop of the 2072 blockade and the Madhesh movement. The Construction of Highway was enunciated without the preparation of an Environmental Impact Assessment Report despite the fact that it required EIA before the implementation of the big physical plan of long-term importance. Only the paper works were done on the study and design of the alternative highway concept. The required reports and construction laws were abolished from the psychology that strong reporting like EIA could be a hindrance to the roads being constructed through sensitive terrain like Chure (Siwalik). • During the widening of the roads, 8 thousand 2 hundred and 55 different trees of community forest of Makwanpur, Sindhuli and Udaypur districtsare cut. -

Rakam Land Tenure in Nepal

47 TRENDS OF WOMEN'S CANDIDACY IN NATIONAL ELECTIONS OF NEPAL Amrit Kumar Shrestha Lecturer (Political Science) Mahendra Multiple Campus, Dharan [email protected] Abstract The study area of this article is women's candidacy in national elections of Nepal. It focuses on five national elections held from 1991 to 2013. It is based on secondary source of data. The Election Commission of Nepal publishes a report after every election. Data are extracted from the reports published by the Election Commission and analyzed with the help of the software SPSS. This article analyzes only facts regarding the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system. Such a study is important in order to lead to new affirmative action policies that will enhance gender mainstreaming and effective participation in all leadership and development processes. The findings will also be resourceful to scholars who are working in this field. The findings from this investigation provide evidence that the number of women candidates in national elections seems almost invisible in an overwhelming crowd of men candidates. The number of elected women candidates is very few. Similarly, distribution of women candidates is unequal in geographical regions. Where the human development rate is high the number of women candidates is greater. The roles of political parties of Nepal are not profoundly positive to increase women's candidacy. Likewise, electoral systems are responsible to influence women‟s chances of being elected. FPTP electoral system is not more favorable for women candidates. This article recommends that if a constituency would reserve only for women among three through FPTP then the chances of 33 percent to win the elections by women would be secured. -

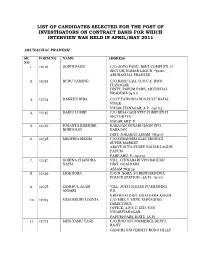

List of Candidates Selected for the Post of Investigators on Contract Basis for Which Interview Was Held in April/May 2011

LIST OF CANDIDATES SELECTED FOR THE POST OF INVESTIGATORS ON CONTRACT BASIS FOR WHICH INTERVIEW WAS HELD IN APRIL/MAY 2011 ARUNACHAL PRADESH SR. FORM NO NAME ADDRESS NO 1. 12/16 GOPIN PADU C/O GOTO PADU, BSNL COMPLEX, G- SECTOR, NAHAR LAGUN-791110, ARUNACHAL PRADESH 2. 12/23 BURU TAMING C/O BARU LALI, O/O C.E. RWD. ITANAGAR DISTT. PAPUM PARE, ARUNCHAL PRADESH-791111 3. 12/24 DAKKEN RIBA C/O T.TAIPODIA M/S PULU BAJAJ, VIVEK VIHAR,ITANAGAR, A.P. -791113 4. 12/35 DAKLI LOMBI C/O BIDA GADI KVIC COMPLEX H SECTOR ITA NAGAR ARU. P 5. 12/36 DIGANTA KISHORE KAKAJAN SONARI GAON VPO BORDOLOI KAKAJAN DIST. JORAHAT ASSAM 785107 6. 12/38 MEGHNA SIKOM C/O SUBANSIRI ELECTRONICS SUPER MARKET ABOVE SUTA STORE NAHAR LAGUN PAPUM PARE ARU. P.-791110 7. 12/47 GOBINA CHANDRA VILL. CHINABARI VPO BAGUAN NATH DIST. GOALPARA ASSAM 783129 8. 12/49 LIGE SORA C/O N. SORA S I BENDARDEWA POLICE STATION –(A.P)- 791111 9. 12/58 ZAHIDUL ALAM VILL. JOYTI NAGAR PO.KRISHNA ANSARI P.S. KRISHNAI DIST. GOALPARA ASSAM 10. 12/65 MISS RECHI LOGNIA C/O MRS. I. MIZE, MANAGING DIRECTOR'S OFFICE, A.P.F.C. LTD, VAN VIHARITANAGAR, PAPUM-PARE DISTT. (A.P) 11. 12/73 MISS YAMU TAGE C/O HOD OF COMMERCE DEPTT. RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY RONO HILLS DOIMUKH DIST- PAPUM PARE ITANAGAR (A.P)- 791112 12. 12/90 SUSHIL HAZARIKA JORHAT GOVT BOYS H.S. & M.P. SCHOOL JORHAT, DISTT-JORHAT ,ASSAM-785001 13. 12/91 JAYANTA KUMAR C/O LATE PADMA DHAR BANIA, BANIA VILL. -

Breaking the Barriers

Breaking the barriers Women make up 20 percent of the total mobile masons which is an unprecedented feat considering that masonry, and the construction sector, have conventionally been male-dominated. Inside Good governance in reconstruction | PMO gets new office | Kasthamandap almost complete Inside Reconstruction of Ranipokhari begins | Housing grants simplified | Foreign aid in numbers Inside Helambu returning to past glory | Tembathang promotes Hyolmo culture | Public hearing in Melamchi Inside Donors pledge further support | Laprak settlement in final stage | Rs.141 billion for post-quake rebuilding Inside 62,000 delisted from beneficiary list | Pilachhen under construction | List of reconstructed heritage sites You can obtain the previous editions of ‘Rebuilding Nepal’ from NRA office at Singha Durbar. Cover: Women masons taking part in a training program held in Gorkha. Photo: UNDP NRA LATEST Second fourth quarter progress of NRA 20,255 beneficiaries added, 92 pc signed agreement NRA The National Reconstruction Authority held a meeting to review the progress made in the second fourth quarter of this current fiscal year. The National Reconstruction Author- During the review period, 36,050 Similarly, out of 147 health center ity (NRA) held a meeting to review the private houses have been reconstructed buildings to be built under the Indian progress made in the second fourth quar- while 28,872 beneficiaries have started government grant, review is ongoing of ter of this current fiscal year. to construct their houses damaged in the tender to construct 33 centers and agree- The review was held of the NRA ac- April 2015 earthquake. ment has been reached with the Indian tivities and physical and fiscal progress in According to the NRA ’s Central Level Embassy to rebuild 121 health centers, the post-earthquake reconstruction held Project Implementation Unit (Education), according to the Central Level Project from November 16, 2020 to March 13, 161 more schools have been rebuilt which Implementation Unit (Building). -

Pollution and Pandemic

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 253 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 31.2 C -0.7 C Monday, November 09, 2020 | 24-07-2077 Biratnagar Jumla As winter sets in, Nepal faces double threat: Pollution and pandemic Studies around the world show the risk of Covid-19 fatality is higher with longer exposure to polluted air which engulfs the country as temperatures plummet. ARJUN POUDEL Kathmandu, relative to other cities in KATHMANDU, NOV 8 respective countries. Prolonged exposure to air pollution Last week, a 15-year-old boy from has been linked to an increased risk of Kathmandu, who was suffering from dying from Covid-19, and for the first Covid-19, was rushed to Bir Hospital, time, a study has estimated the pro- after his condition started deteriorat- portion of deaths from the coronavi- ing. The boy, who was in home isola- rus that could be attributed to the tion after being infected, was first exacerbating effects of air pollution in admitted to the intensive care unit all countries around the world. and later placed on ventilator support. The study, published in “When his condition did not Cardiovascular Research, a journal of improve even after a week on a venti- European Society of Cardiology, esti- lator, we performed an influenza test. mated that about 15 percent of deaths The test came out positive,” Dr Ashesh worldwide from Covid-19 could be Dhungana, a pulmonologist, who is attributed to long-term exposure to air also a critical care physician at Bir pollution. -

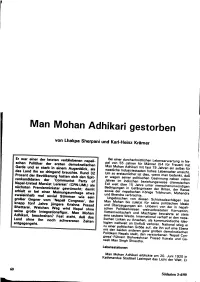

Man Mohan Adhikari Gestorben

Man MohanAdhikari gestorben von Lhakpasherpani und Karr-HeinzKrämer Er war einer der letzten verHiebenen-Aär-ofr"tischen nepali_ Beieiner durchschni_ttlichen Lebenserwartung pal von in Ne_ qchen Politiker der ersten 55 Jahren.tttrMjnnei-tlä-i.i, Frauen) Garde Man Adhikari hat und er starb in einem Ärg;iHi"t, "r" .Mohan mit taCi'iö i;r;; ein setbstfür das Land ihn westticheIndustriestaaten hohei LäOeäsalter so dringendUrau"frie. Rund 32 Um so erstauntiche, erreicht. Prozentder Bevölkerunghatten iiiäiel,-öänffiä bedenkt,daß Scfr AenSpit- er wegenseiner oolitischen Gesinnung zenkandidaten der Jahren nebenüiefän -ögmmuni.f-'p"rtv of im indischen.Ueziehung;;;ü ";;;.il"nunwürdisen chinesischen Nepat-UnitedMarxist lehnisti-iöit-urur-t Exitweit über 1s .tanre nächsten premierminister "r" uni;; g"*ün"älrt; damit Bedinsunsenin Geräno19iäi.j;;'bä;^, erhiett soy,:. der. der Ranas er bei einer Meirüd;i;;ge nepalischen-KOnig"niUtur"n, Mahendra zwoieinhalb otwa und Birendraverbrachte. mal soviel StiÄmen-Lie sein großer Gegner vom 'Nepali Ungebrochenvon. Schicksalsschtägen Congress,,der Man bis zutetzifies91 trat Jahre K-ri"ffi; prasad -Mohan rti; ä;;iiti""n"n tdeate !l"pp {ünf itingää-w;s y1j UUgrz.gugungenein. Unbeirft ",-;'der Bhattarai. Wetchen *iiJ--äääar schen Politikerkreisen in nepati_ große ohne _weitverUreiiäien"Läri"nrteKorruption, :"i:rg tntegrationöfigur,M;; Mohan Vetternwirtschaft una rvtaätriöiJi Adhikari, einesaubere er stets beschreiien?resi-steii]''o"g 0"" Weste.tnternaliäia,r'";rh"if er Land lischenLinken den nepa_ ohne ihn noch *d;;;;;n Zeiten zu Alge-fre1;;tr- tö;Jnistiscne roeo_ entgegengeht. logienwettweit an Einftuß'*rt"ä.'iv;iionat stieg er zu einerpolitischen Größe ."f, mit äi"'t ^ äLt "in" Ebene den beidenanderen ganz großendemokratischen Potitikern.Nepatssteut, aä" ,rrr"p"ti gress'-Führern ""!lääänäi Con- Bishweshwarp;;;aä'K;irata '---- '\vr und neshMan Singh Shrestha.