The Current Status of Technology in Education: Lightspeed Ahead with Mild Turbulence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edutainment Case Study

What in the World Happened to Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned Carly Shuler The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop Fall 2012 1 © The Joan Ganz Cooney Center 2012. All rights reserved. The mission of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop is to harness digital media teChnologies to advanCe Children’s learning. The Center supports aCtion researCh, enCourages partnerships to ConneCt Child development experts and educators with interactive media and teChnology leaders, and mobilizes publiC and private investment in promising and proven new media teChnologies for Children. For more information, visit www.joanganzCooneyCenter.org. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center has a deep Commitment toward dissemination of useful and timely researCh. Working Closely with our Cooney Fellows, national advisors, media sCholars, and praCtitioners, the Center publishes industry, poliCy, and researCh briefs examining key issues in the field of digital media and learning. No part of this publiCation may be reproduCed or transmitted in any form or by any means, eleCtroniC or meChaniCal, inCluding photoCopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. For permission to reproduCe exCerpts from this report, please ContaCt: Attn: PubliCations Department, The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop One Lincoln Plaza New York, NY 10023 p: 212 595 3456 f: 212 875 7308 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Shuler, C. (2012). Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. -

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Intel Corporation Annual Report 1999

clients networking and communications intel.com 1999 annual report the building blocks of the internet economy intc.com server platforms solutions and services 29.4 30 2.25 90 2.11 26.3 1.93 25.1 1.73 20.8 20 1.45 1.50 60 16.2 1.01 11.5 10 0.75 30 8.8 0.65 0.65 High 5.8 4.8 3.9 0.31 Close 0.24 0.20 Low INTEL CORPORATION 1999 0 0 0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 Net revenues Diluted earnings per share Stock price trading ranges (Dollars in billions) (Dollars, adjusted for stock splits) by fiscal year (Dollars, adjusted for stock splits) 3,111 1999 facts and figures 3,000 45 2,509 Intel’s stock 38.4 2,347 35.5 35.6 price has risen 33.3 2,000 28.4 30 1,808 27.3 at a 48% 26.2 21.2 21.6 20.4 1,296 1,111 970 compound 1,000 15 780 618 517 annual growth 0 rate in the 0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 Research and development Return on average (Dollars in millions, excluding purchased last 10 years. stockholders’ equity in-process research and development) (Percent) 9.76 4,501 9 Japan 4,500 7% 4,032 7.05 3,550 3,403 3,024 5.93 6 Asia- 3,000 Pacific North 5.14 23% America 2,441 43% 1,9 33 3.69 2.80 3 1,500 1,228 2.24 Machinery 948 & equipment 1.63 1.35 Europe 680 1.12 27% Land, buildings & improvements 0 0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 Book value per share Geographic breakdown of 1999 revenues Capital additions to property, at year-end (Percent) plant and equipment† (Dollars, adjusted for stock splits) (Dollars in millions) Past performance does not guarantee future results. -

The Future of the Microprocessor Industry”

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 15.912 Technology Strategy Professor Rebecca Henderson “The Future of the Microprocessor Industry” Final Paper Juan Chaia Paulo Marchesan Bernardo Neves Cambridge, Massachusetts. May 11th, 2005 15.912 Technology Strategy Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Rebecca Henderson Sloan School of Management EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Intel has been one of the most successful companies in modern corporate history. They are the clear leader in the microprocessor industry, in which they have set the pace of technological advance in the past three decades. They were able to do this because of the uniqueness of its technology at the beginning, and the development of strong complementary assets, namely manufacturing expertise and branding, later on. As a consequence, Intel has been able to capture a significant portion of the value created by the microprocessor industry. However, the electronic microprocessor technology is reaching maturity, and may be subject to a disruption within the next two decades. In this paper, we predict that such disruption may come from microphotonics. Microphotonics technology, which very crudely uses photons for the transmission and processing of data, has been on the spotlight for at least a decade. According to experts from MIT, it may be ready to be used on commercial chips in a decade. Some large companies around the world, such as Pirelli, IBM, Lucent and others, are already making big bets that this will be the next chip technology. Our paper microphotonics analyzes different scenarios that the industry leader, Intel, may face if indeed microphotonics turns out to be the disruptive technology in the microprocessor industry. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

Finding Aid to the Brøderbund Software, Inc. Collection, 1979-2002

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Brøderbund Software, Inc. Collection Finding Aid to the Brøderbund Software, Inc. Collection, 1979-2002 Summary Information Title: Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection Creator: Douglas Carlston and Brøderbund Software, Inc. (primary) ID: 114.892 Date: 1979-2002 (inclusive); 1980-1998 (bulk) Extent: 8.5 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are in English, unless otherwise indicated. Abstract: The Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection is a compilation of Brøderbund business records and information on the Software Publishers Association (SPA). The majority of the materials are dated between 1980 and 1998. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, he has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection was donated to The Strong in January 2014 as a gift from Douglas Carlston. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 114.892. The papers were received from Carlston in 5 boxes, along with a donation of Brøderbund software products and related corporate ephemera. Preferred citation for publication: Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection, Brian Sutton- Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong Processed by: Julia Novakovic, February 2014 Controlled Access Terms Personal Names • Carlston, Cathy • Carlston, Doug, 1947- • Carlston, Gary • Pelczarski, Mark • Wasch, Ken • Williams, Ken Corporate Names • Brøderbund • Brøderbund Software, Inc. -

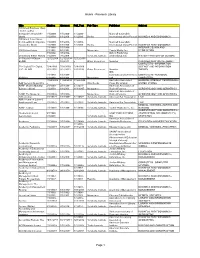

Research Library Page 1

Alumni - Research Library Title Citation Abstract Full_Text Pub Type Publisher Subject 100 Great Business Ideas : from Leading Companies Around the 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 100 Great Sales Ideas : from Leading Companies 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish Around the World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- INTERIOR DESIGN AND 1001 Home Ideas 6/1/1991 6/1/1991 Magazines Family Media, Inc. DECORATION 3/1/2002- 3/1/2002- Oxford Publishing 20 Century British History 7/1/2009 7/1/2009 Scholarly Journals Limited(England) HISTORY--HISTORY OF EUROPE 33 Charts [33 Charts - 12/12/2009 12/12/2009- 12/12/2009 BLOG] + 6/3/2011 + Other Resources Newstex CHILDREN AND YOUTH--ABOUT COMPUTERS--INFORMATION 50+ Digital [50+ Digital, 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- SCIENCE AND INFORMATION LLC - BLOG] 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 Other Resources Newstex THEORY IDG 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- Communications/Peterboro COMPUTERS--PERSONAL 80 Micro 6/1/1988 6/1/1988 Magazines ugh COMPUTERS 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 Australian Associated GENERAL INTEREST PERIODICALS-- AAP General News Wire + + + Wire Feeds Press Pty Limited UNITED STATES AARP Modern Maturity; 2/1/1988- 2/1/1988- 2/1/1991- American Association of [Library edition] 1/1/2003 1/1/2003 11/1/1997 Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS American Association of AARP The Magazine 3/1/2003+ 3/1/2003+ Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS ABA Journal 8/1/1972+ 1/1/1988+ 1/1/1992+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW MEDICAL SCIENCES--NURSES AND ABNF Journal 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ Scholarly Journals Tucker Publications, Inc. -

The History of Educational Computer Games

Beyond Edutainment Exploring the Educational Potential of Computer Games By Simon Egenfeldt-nielsen Submitted to the IT-University of Copenhagen as partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree February, 2005 Candidate: Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen Købmagergade 11A, 4. floor 1150 Copenhagen +45 40107969 [email protected] Supervisors: Anker Helms Jørgensen and Carsten Jessen Abstract Computer games have attracted much attention over the years, mostly attention of the less flattering kind. This has been true for computer games focused on entertainment, but also for what for years seemed a sure winner, edutainment. This dissertation aims to be a modest contribution to understanding educational use of computer games by building a framework that goes beyond edutainment. A framework that goes beyond the limitations of edutainment, not relying on a narrow perception of computer games in education. The first part of the dissertation outlines the background for building an inclusive and solid framework for educational use of computer games. Such a foundation includes a variety of quite different perspectives for example educational media and non-electronic games. It is concluded that educational use of computer games remains strongly influenced by educational media leading to the domination of edutainment. The second part takes up the challenges posed in part 1 looking to especially educational theory and computer games research to present alternatives. By drawing on previous research three generations of educational computer games are identified. The first generation is edutainment that perceives the use of computer games as a direct way to change behaviours through repeated action. The second generation puts the spotlight on the relation between computer game and player. -

Arthur Kindergarten 2001 User's Guide

Table of Contents Welcome! ......................................................................................................................2 System Requirements................................................................................................3 Installation Instructions............................................................................................4 The Options Screen....................................................................................................5 Windows...................................................................................................................5 Macintosh .................................................................................................................6 Getting Around the Program ...................................................................................7 Preferences Screen...................................................................................................8 Progress Checker.....................................................................................................9 Goal Checker..........................................................................................................10 Character Descriptions............................................................................................11 Playing Disc 1 Activities.........................................................................................15 Picture Windows...................................................................................................15 -

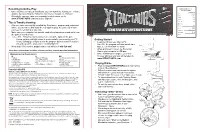

STARTER KIT INSTRUCTIONS Paper Stock: White Offset • Make Sure Your Computer Has Sounds Enabled and Speakers Turned on to Hear Paper Weight: 70 Lb

Returning to Online Play INSTRUCTION SHEET 6+ SPECIFICATIONS • Once you have completed installation, you can launch the Xtractaurs™ website Toy: STARTER KIT anytime by connecting the Extraction Gun to your computer’s USB port. Toy No.: P7218 • Alternately, you may open your computer’s web browser, go to Part No.: 0920 www.XTRACTAURS.com and select “Sign In.” Trim Size: A5 Tips & Troubleshooting Folded Size: A6 Type of Fold: • After you have successfully installed the Xtractaurs™ program and registered One ™ # colors: online, you do not need to install the CD again to play. Keep the CD in case Colors: Black you need to reinstall at a later date. STARTER KIT INSTRUCTIONS Paper Stock: White Offset • Make sure your computer has sounds enabled and speakers turned on to hear Paper Weight: 70 lb. the game's sound effects. EDM No.: • To see if the Extraction Gun is connected, look at the lights on the gun: ○ A slow, pulsing red light means it is successfully connected to your PC. Getting Started ○ A fast, flashing green light means the program did not install. Reload the • Load the CD into your Mac or PC. CD and repeat the steps under “Getting Started.” • On a PC, the program will auto install; on a • Need help? Visit service.mattel.com or call toll-free 1-800-524-8697. Mac, select “RUN ME” to install. • When prompted, connect the Extraction Keep these instructions for future reference as they contain important information. Gun to your computer’s USB port. Minimum System Requirements • Once installation is complete, your web All PC MAC browser will open and you will be taken to • USB 2.0 • Windows XP/Vista OS • OS 10.5 (Leopard) or higher www.XTRACTAURS.com. -

Amy Clary: "Digital Nature: Uru and the Representation of Wilderness in Computer Games"

Digital Nature: Uru and the Representation of Wilderness in Computer Games Amy Clary The desert is intense. The parched red earth bakes under the relentless glare of the afternoon sun. Thirsty-looking clumps of sage, too squat and sere to cast much shadow, dot the dry, cracked land. On the barbed wire fence is a sign, sunbleached and wind- scoured, that reads “No Trespassing” and “New Mexico.” A rusty Airstream trailer blends into the unforgiving landscape like the shell of a desert tortoise. Two oases of shade beckon: one under the awning of the vintage Airstream, another cast by a distant red rock butte. I head toward the butte, eager to explore its alluringly steep slopes and jagged profile. I climb up the slope and realize that it is not a butte at all but the entrance to a sort of canyon, a cleft, with a seductive assortment of shapes and shade inside it. I take anoth- er step and … the whole world dissolves into unintelligible poly- gons of color. All I see is chaos, and try as I might, I can’t get back to the desert. Such are the frustrations of playing Uru: Ages Beyond Myst (Cyan Worlds, 2003) on a computer that barely meets the game’s mini- mum system requirements. Reviewer Darryl Vassar writes, “Uru will make even the beefiest video card sweat at the highest detail settings…” (“Incomparable beauty” section: para. 4). I had hoped that by turning the game’s graphics settings down to the bare-bones level, my processor, video card, and memory would be sufficient to the task, but they were not. -

Samples - Five Day Unit Plan Summary Grade Two Teacher’S Guide Code: TH09

Includes FREE resources! Now you can make phonics fast and fun with this FREE sample lesson. It’s packed full of teaching ideas and contains everything you need to teach the r-controlled syllable and the digraph ‘ar’. What’s more, there are FREE audio and software demos on the resource CD! In this Sample Lesson: On the Resource CD: th On e • Grade Two Teacher’s Guide: • Story Phonics Software r e D s C • Five Day Unit Plan Summary p2 • Letter Sound Cards: m, ar, ource • The Robot Syllable with Arthur Ar ch, h, a/ŭ/, l, n, or, th and Orvil Or: ar, or p3-5 • Blends & Digraphs Song: ar • Picture Code Cards: ar p6 • Plus lots more! • Far Beyond ABC book: ar p7 • Grade Two Teacher’s Guide CD: • Student List p8 • Review Sentences p8 • Word Detectives p9 • Word Sort p9 • Unit Story: The Porcupine Report p10-11 • Blends & Digraphs Copymaster: ar p12 • Word Bank Copymaster: ar p13 • Grade Two Word Card Samples p14 www.letterland.com Samples - Five Day Unit Plan Summary Grade Two Teacher’s Guide Code: TH09 Five Day Unit Plan Each Unit follows this same five day plan. You may also want to print out the convenient Daily Lesson Guide Cards from the resource CD. Whole Class Small Group Independent/Partner Homework • Phonics concept review • Teacher builds words for reading • Write words and sentences, • Read the Student • Introduce concepts on the • New Tricky Words Read to two partners List pocket chart • Read the Student List • Beyond ABC or Far Beyond ABC (for some lessons) Day 1 • ‘Live Reading’ Overview of • Read new Word Cards • Quick Dash