Tech Power: a Critical Approach to Digital Corporations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Autonomous Power of the State

The autonomous power of the state : its origins, mechanisms and results Author(s): MICHAEL MANN Source: European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie, Vol. 25, No. 2, Tending the roots : nationalism and populism (1984), pp. 185-213 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23999270 Accessed: 14-09-2017 18:37 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie This content downloaded from 140.180.248.195 on Thu, 14 Sep 2017 18:37:47 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms MICHAEL MANN The autonomous power of the state , its origins, mechanisms and results This essay tries to specify the origins, mechanisms and results of the autonomous power which the state possesses in relation to the major power groupings of 'civil society'. The argument is couched generally, but it derives from a large, ongoing empirical research project into the development of power in human societ ies (i). At the moment, my generalisations are bolder about agrar ian societies ; concerning industrial societies I will be more tentative. -

Empire, Or Multitude Transnational Negri

Empire, or multitude Transnational Negri John Kraniauskas With the publication of Empire,* the oeuvre of the the authors offer us ʻnothing less than a rewriting Italian political philosopher and critic Antonio Negri of The Communist Manifesto for our timeʼ which – until recently an intellectual presence confined to ʻring[s] the death-bell not only for the complacent the margins of Anglo-American libertarian Marxist liberal advocates of the “end of history”, but also for thought – has been transported into what is fast pseudo-radical Cultural Studies which avoid the full becoming an established and influential domain of confrontation with todayʼs capitalismʼ. One effect of transnational cultural theory and criticism. Michael such praise, however, is that Empire is freighted with Hardtʼs mediating role, as translator of key texts by the difficult task of having to live up to itself, as its Negri and other radical Italian intellectuals (such as eulogists have portrayed it. Paulo Virno), and now as co-author of Empire itself, There is some truth in the words (become advertising) has been crucial over the years in helping to establish of these critics. On the one hand, Empire is indeed a and maintain his reputation. Published by Harvard grand work of synthesis, but a synthesis primarily of University Press, the book comes to us with the stamp the work of Negri himself. Over approximately thirty of approval of important contemporary critics – politi- years of writing, much of it spent in prison and exile, cal philosopher Étienne Balibar, subalternist historian Negri has creatively engaged with: transformations in Dipesh Chakrabarty, Marxist cultural critic Fredric the forms of capital accumulation, class recomposition Jameson, urban sociologist Saskia Sassen, Slovenian and working class ʻself-valorizationʼ; the writings of critic-at-large Slavoj Žižek and novelist Leslie Marmon Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Silko – whose words dazzle the potential reader from amongst others; and the political philosophy of Spinoza the bookʼs dust jacket. -

As Detained for 437 Days in China’S Sprawling New System of Incarceration and Indoctrination

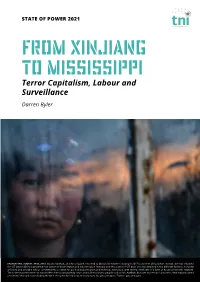

STATE OF POWER 2021 From Xinjiang to Mississippi Terror Capitalism, Labour and Surveillance Darren Byler KAZAKHSTAN, ALMATY, APRIL 2019: Gulzira Auelhan, an ethnic Kazakh, returned to China’s far western Xinjiang in 2017 to visit her ailing father. Instead, she was detained for 437 days in China’s sprawling new system of incarceration and indoctrination. Instead, over the course of 437 days, she was detained in five different facilities, including a factory and a middle school converted into a centre for political indoctrination and technical instruction, with several interludes of a form of house arrest with relatives. The Chinese government has said it offers free vocational education and skills training to people such as Ms. Auelhan. But over more than 14 months, “that training lasted one week,” she said, not including the time she spent forced to work in a factory. IG: @noorimages / Twitter: @noorimages The Chinese state within Xinjiang has forged a form of capitalist frontier-making based on data harvesting and unfree human labour that exploits ethno-racial difference in order to generate new forms of capital accumulation and coercive state power. ‘Where is your ID!’ the police contractor yelled at me in Uyghur. I looked up in surprise. I had been avoiding eye contact, trying to attract as little attention as possible. In April 2018, in the tourist areas of Kashgar – where there were checkpoints every 200 metres – the contractors usually recognised a bespectacled white person as a foreigner. But over the years that I had lived and worked as an anthropologist in Northwest China I had often been mistaken for a Uyghur. -

Maurizio Lazzarato. Governing by Debt. Trans. JD Jordan. Los Angeles

Maurizio Lazzarato. Governing by Debt. Trans. J. D. Jordan. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2013. Pp. 280. Maurizio Lazzarato. Signs and Machines: Capitalism and the Production of Subjectivity. Trans. J.D. Jordan. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2014. Pp. 280 Maurizio Lazzarato is an Italian sociologist and philosopher who lives and works in France. He collaborated on collective works with important figures like Antonio Negri and Yann Moulier-Boutang in the 1990s and has been a frequent contributor to the journal Multitudes in which the same two intellectuals were also leading voices. During the same period, he was closely involved as a theorist and activist in the long and inventive struggle of the intermittents du spectacle, French cultural workers defending a social security regime that took particular account of their unstable employment and the way in which their creativity overflowed their periods of paid activity. This involvement fed into a broader reflection and theorization around mutations of labor, the rise of precariousness, neo-liberal governance and leftist mobilization that found expression in a range of texts published in the 2000s. Lazzarato came forcefully to public attention in the English-speaking world when his timely, important book on debt, La Fabrique de l’homme endetté, was translated into English as The Making of the Indebted Man in 2013. That book came out of his broader concern with neo-liberal governance and the subjectivities associated with it, but it was tightly focused on debt. The two books to be discussed here return to that larger picture, the prime focus of Governing by Debt being neo-liberal governance and that of Signs and Machines, the production of subjectivity under capitalism. -

An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida

Conductive Capacity of The State 1 Conductive Capacity of The State: An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida Initiative By Jose Pablo Olvera An Applied Research Project Submitted to the Department of Public Administration Texas State University-San Marcos In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Public Administration Spring 2017 Dr. Patricia Shields Christopher Brown, JD Ms. Alejandra Pena, MPA Conductive Capacity of The State 2 Abstract The purpose of this applied research paper is to conduct a preliminary assessment of Mexico’s political institutions since the Merida Initiative to evaluate the progress, or lack thereof, in relation to the agreement’s explicit goals of institutionalizing reforms and supporting democratic governance. The project’s framework is structured using three core pillar questions that address Mexican state capacities: coercive, extractive, and conductive capacity. Conductive capacity refers to the state’s ability to effectively channel citizen demands through the state apparatus. First, an assessment of Mexico’s political institutions is performed using a variety of methods, including data, survey-item, and case study analyses. Second, the dimension of conductive capacity is tested against coercive and extractive capacities to evaluate whether an interaction between these exists. The results of the assessment demonstrate that the Mexican state’s coercive and conductive capacities have significantly decreased since the implementation of the Merida Initiative, while demonstrating that coercive and extractive capacities of the state significantly predict conductive capacity dimension variables. Conductive Capacity of The State 3 Acknowledgments I would like to begin by thanking my parents, Alfonso and May, for their sacrifice made when they decided to leave almost everything behind so that my siblings and I could have a chance at a better future. -

Part I INTRODUCTION

Part I INTRODUCTION 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 1 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:380:30:38 PPMM 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 2 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:390:30:39 PPMM 1 Republics of the Possible State Building in Latin America and Spain Miguel A. Centeno and Agust í n E. Ferraro Introduction Latin American republics were among the fi rst modern political entities designed and built according to already tried and seemingly successful institutional mod- els. During the wars of independence and for several decades thereafter, pub- lic intellectuals, politicians, and concerned citizens willingly saw themselves confronted with a sort of void, a tabula rasa. Colonial public institutions and colonial ways of life had to be rejected, if possible eradicated, in order for new political forms and new social mores to be established in their stead. However, in contrast to the French or American revolutions, pure political utopias did not play a signifi cant role for Latin American institutional projects. The American Revolution was a deliberate experiment; the revolutionar- ies fi rmly believed that they were creating something new, something never attempted before. The French revolutionaries dramatically signaled the same purpose by starting a whole new offi cial calendar from year one. In contrast, Latin American patriots assumed that proven and desirable institutional mod- els already existed, and not just as utopic ideals. The models were precisely the state institutions of countries that had already undergone revolutions or achieved independence, or both: Britain , the United States, France, and others such as the Dutch Republic . -

A-Signifying Communication in Lazzarato and Preciado1 Crítica E Contágio: Comunicação Assignificante Em Lazzarato E Preciado

181 Criticism and contagion: a-signifying communication in Lazzarato and Preciado1 Crítica e contágio: comunicação assignificante em Lazzarato e Preciado DEMÉTRIO ROCHA PEREIRAa Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Post-Graduate Program in Communication. Porto Alegre – RS, Brasil ALEXANDRE ROCHA DA SILVAb Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Post-Graduate Program in Communication. Porto Alegre – RS, Brasil ABSTRACT This article addresses the distinction between signifying and asignifying semiotics, conceived by Félix Guattari and continued by Maurizio Lazzarato in the scope of a 1 This work was supported by CNPq and Capes. critique of contemporary modes of capitalist production. For Lazzarato, investigating a PhD student of the the significant level is not only insufficient, but it helps to conceal the machinic Communication and effectiveness of the asignifying level. By recognizing this as an epistemological problem, Information Program at the Universidade Federal do Rio we discuss the significance of considering articulations between these levels so that Grande do Sul (UFRGS). Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000- the asignifying becomes intelligible. Thus, we suggest that the experimental attitude 0003-0762-8469. E-mail: of Paul B. Preciado provides a useful route for the investigation and translation of [email protected] specific asignifying operations. b Professor of the Graduate Program in Communication Keywords: Asignifying semiotics, Lazzarato, Preciado, communication at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). CNPQ Productivity Scholarship RESUMO Holder. Postdoctoral fellow Este artigo aborda a distinção entre semiologia significante e semiótica assignificante, with CNPq scholarship. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002- concebida por Félix Guattari e retomada por Maurizio Lazzarato no escopo de uma 1194-6438. -

The Social Origins of State Power in China by Daniel Christopher

The Social Origins of State Power in China by Daniel Christopher Mattingly A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kevin J. O'Brien, Chair Professor Ruth Berins Collier Professor Peter L. Lorentzen Professor Noam Yuchtman Summer 2016 The Social Origins of State Power in China Copyright 2016 by Daniel Christopher Mattingly 1 Abstract The Social Origins of State Power in China by Daniel Christopher Mattingly Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Kevin J. O'Brien, Chair This dissertation investigates the origins of state power and political accountability. How do states exercise political control over their populations and implement policies that have clear winners and losers? Do democratic institutions in combination with a strong civil society strengthen political accountability? I examine these questions in the context of rural China, which combines limited local democracy and vibrant non-state groups such as kinship associations, temples, and neighborhood groups. Many argue that strong civil society institutions and local elections can curb the power of the state and hold government officials accountable. However, in this dissertation I argue that in China, strong civil society groups and village elections have expanded state power and helped officials confiscate wealth. The first part of the dissertation develops my theory of state power. Drawing on new data from rural China, I show that citizens distrust the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and believe that local party cadres do not represent their interests. -

SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies

School of Oriental and African Studies University of London SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies No. 38 The Rhetorical Power of Neo-Liberalism and the Strengthening of the Korean State David Hundt February 2013 http://www.soas.ac.uk/japankorea/research/soas-aks-papers/ SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies, No. 38 February 2013 The Rhetorical Power of Neo-Liberalism and the Strengthening of the Korean State NOT FOR CITATION. COMMENTS AND FEEDBACK WELCOME. David Hundt Deakin University [email protected] © 2013 http://www.soas.ac.uk/japankorea/research/soas-aks-papers/ The Rhetorical Power of Neo-Liberalism and the Strengthening of the Korean State Abstract: This article tests the assumption that neo-liberalism inevitably detracts from state strength by analysing the power of the Korean state since the Asian economic crisis. Despite expectations to the contrary, the state has retained its influential position as economic manager, thanks to a combination of two types of power: the repressive powers of the developmental state, and crucially, powers stemming from neo-liberalism itself. The Korean state used both these resources, which amount to the full spectrum of what Michael Mann refers to as infrastructural power, in its social and political struggle with civil society over economic policy. Rather than being a disempowering force, neo-liberal reform enhanced the political position of the Korean state, which presented itself as an agent capable of resolving long-standing economic problems, defending law and order, and attracting the support of democratic forces. Our findings suggest that neo-liberalism offers some states the opportunity to remain weighty economic actors, and developmental states may be particularly adept at co-opting elements of civil society into governing alliances. -

Immaterial Labor Maurizio Lazzarato

Immaterial Labor Work, Migration, Memes, Personal Geopolitics Immaterial Labor Maurizio Lazzarato A significant amount of empirical research has been conducted concerning the new forms of the organization of work. This, combined with a corresponding wealth of theoretical reflection, has made possible the identification of a new conception of what work is nowadays and what new power relations it implies. An initial synthesis of these results-framed in terms of an attempt to define the technical and subjective-political composition of the working class can be expressed in the concept of immateral labor, which is defined as the labor that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity. The concept of immaterial labor refers to two different aspects of labor. On the one hand, as regards the “informational content” of the commodity, it refers directly to the changes taking place in workers’ labor processes in big companies in the industrial and tertiary sectors, where the skills involved in direct labor are increasingly skills involving cybernetics and computer control (and horizontal and vertical communi- cation). On the other hand, as regards the activity that produces the “cultural content” of the commodity, immaterial labor involves a series of activities that are not normally recognized as “work” in other words, the kinds of activities involved in defining and fixing cultural and artistic standards, fashions, tastes, consumer norms, and, more strategically, public opinion. Once the privileged domain of the bourgeoi- sie and its children, these activities have since the end of the 1970s become the domain of what we have come to define as “mass intellectuality.” The profound changes in these strategic sectors have radically modified not only the composition, management, and regulation of the workforce–the organization of production–but also, and more deeply, the role and function of intellectuals and their activities within society. -

© 2016 Miriam Tola ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2016 Miriam Tola ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ECOLOGIES OF THE COMMON: FEMINISM AND THE POLITICS OF NATURE by MIRIAM TOLA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Women’s and Gender Studies Written under the direction of Ed Cohen and Elizabeth Grosz ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- New Brunswick, New Jersey OCTOBER 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ECOLOGIES OF THE COMMON: FEMINISM AND THE POLITICS OF NATURE By MIRIAM TOLA Dissertation Directors: Ed Cohen, Elizabeth Grosz This dissertation proposes a theory of the common beyond the modern figure of Man as primary agent of historical transformation. Through close reading of Medieval debates on poverty and common use, contemporary political theory and political speeches, legal documents, and protests in public spaces, it complicates current debates on the common in three ways. First, this work contends that the enclosures of pre-modern landholdings, a process the unfolded in connected and yet distinct ways in Europe and the colonies, was entangled with the affirmation of the European white man as proper figure of the human entitled to appropriate the labor of women and slaves, and the material world as resources. Second, it engages contemporary theorists of the common such as Paolo Virno, Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt. Although these authors depart from the prevalent assumptions of modern liberalism (in that they do not take the individual right to appropriate nature as the foundation of political community), their formulation of common is still grounded in Marx’s view of labor as the primary force making the world. -

Infrastructural Exclusion and the Fight for the City: Power, Democracy, and the Case of America’S Water Crisis

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLC\53-2\HLC208.txt unknown Seq: 1 29-OCT-18 9:18 Infrastructural Exclusion and the Fight for the City: Power, Democracy, and the Case of America’s Water Crisis K. Sabeel Rahman* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................. 533 I. INFRASTRUCTURAL EXCLUSION ............................ 536 R A. The Flint water crisis ................................ 536 R B. Mechanisms of infrastructural exclusion ............... 538 R II. TOWARD A POLITICAL THEORY OF INFRASTRUCTURE: POWER, DEMOCRACY, AND THE PUBLIC UTILITY TRADITION .......... 541 R III. CONSTRUCTING INCLUSIVE INFRASTRUCTURE: WATER AND BEYOND ................................................. 547 R A. Mandating water equity .............................. 548 R B. Restoring public (and democratic) utilities ............ 551 R C. Public oversight over the broader water infrastructure ....................................... 554 R 1. The importance of strategic and system-wide public oversight ........................................ 554 R 2. Institutionalizing strategic enforcement ............ 557 R IV. CONCLUSION ............................................ 560 R INTRODUCTION In 2013, government officials in Flint, Michigan, which had been placed under state-appointed emergency management following a long- standing budget crisis, imposed a variety of cost-cutting measures. One of these measures included switching the city’s water supply temporarily to the Flint River. Another decision was made not to spend scarce dollars on treat- ing the water with anti-corrosion agents. The result was a severe erosion of * Assistant Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School; Fellow, Roosevelt Institute. I am grateful to the editors of the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review for inviting me to contribute to this special issue. This paper was first drafted in December 2016. It draws on previous works including Rahman, THE NEW UTILITIES: PRIVATE POWER, SOCIAL INFRASTRUC- TURE, AND THE REVIVAL OF THE PUBLIC UTILITY CONCEPT, 30 CARDOZO L.