The Making of the Indebted Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empire, Or Multitude Transnational Negri

Empire, or multitude Transnational Negri John Kraniauskas With the publication of Empire,* the oeuvre of the the authors offer us ʻnothing less than a rewriting Italian political philosopher and critic Antonio Negri of The Communist Manifesto for our timeʼ which – until recently an intellectual presence confined to ʻring[s] the death-bell not only for the complacent the margins of Anglo-American libertarian Marxist liberal advocates of the “end of history”, but also for thought – has been transported into what is fast pseudo-radical Cultural Studies which avoid the full becoming an established and influential domain of confrontation with todayʼs capitalismʼ. One effect of transnational cultural theory and criticism. Michael such praise, however, is that Empire is freighted with Hardtʼs mediating role, as translator of key texts by the difficult task of having to live up to itself, as its Negri and other radical Italian intellectuals (such as eulogists have portrayed it. Paulo Virno), and now as co-author of Empire itself, There is some truth in the words (become advertising) has been crucial over the years in helping to establish of these critics. On the one hand, Empire is indeed a and maintain his reputation. Published by Harvard grand work of synthesis, but a synthesis primarily of University Press, the book comes to us with the stamp the work of Negri himself. Over approximately thirty of approval of important contemporary critics – politi- years of writing, much of it spent in prison and exile, cal philosopher Étienne Balibar, subalternist historian Negri has creatively engaged with: transformations in Dipesh Chakrabarty, Marxist cultural critic Fredric the forms of capital accumulation, class recomposition Jameson, urban sociologist Saskia Sassen, Slovenian and working class ʻself-valorizationʼ; the writings of critic-at-large Slavoj Žižek and novelist Leslie Marmon Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Silko – whose words dazzle the potential reader from amongst others; and the political philosophy of Spinoza the bookʼs dust jacket. -

Maurizio Lazzarato. Governing by Debt. Trans. JD Jordan. Los Angeles

Maurizio Lazzarato. Governing by Debt. Trans. J. D. Jordan. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2013. Pp. 280. Maurizio Lazzarato. Signs and Machines: Capitalism and the Production of Subjectivity. Trans. J.D. Jordan. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2014. Pp. 280 Maurizio Lazzarato is an Italian sociologist and philosopher who lives and works in France. He collaborated on collective works with important figures like Antonio Negri and Yann Moulier-Boutang in the 1990s and has been a frequent contributor to the journal Multitudes in which the same two intellectuals were also leading voices. During the same period, he was closely involved as a theorist and activist in the long and inventive struggle of the intermittents du spectacle, French cultural workers defending a social security regime that took particular account of their unstable employment and the way in which their creativity overflowed their periods of paid activity. This involvement fed into a broader reflection and theorization around mutations of labor, the rise of precariousness, neo-liberal governance and leftist mobilization that found expression in a range of texts published in the 2000s. Lazzarato came forcefully to public attention in the English-speaking world when his timely, important book on debt, La Fabrique de l’homme endetté, was translated into English as The Making of the Indebted Man in 2013. That book came out of his broader concern with neo-liberal governance and the subjectivities associated with it, but it was tightly focused on debt. The two books to be discussed here return to that larger picture, the prime focus of Governing by Debt being neo-liberal governance and that of Signs and Machines, the production of subjectivity under capitalism. -

A-Signifying Communication in Lazzarato and Preciado1 Crítica E Contágio: Comunicação Assignificante Em Lazzarato E Preciado

181 Criticism and contagion: a-signifying communication in Lazzarato and Preciado1 Crítica e contágio: comunicação assignificante em Lazzarato e Preciado DEMÉTRIO ROCHA PEREIRAa Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Post-Graduate Program in Communication. Porto Alegre – RS, Brasil ALEXANDRE ROCHA DA SILVAb Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Post-Graduate Program in Communication. Porto Alegre – RS, Brasil ABSTRACT This article addresses the distinction between signifying and asignifying semiotics, conceived by Félix Guattari and continued by Maurizio Lazzarato in the scope of a 1 This work was supported by CNPq and Capes. critique of contemporary modes of capitalist production. For Lazzarato, investigating a PhD student of the the significant level is not only insufficient, but it helps to conceal the machinic Communication and effectiveness of the asignifying level. By recognizing this as an epistemological problem, Information Program at the Universidade Federal do Rio we discuss the significance of considering articulations between these levels so that Grande do Sul (UFRGS). Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000- the asignifying becomes intelligible. Thus, we suggest that the experimental attitude 0003-0762-8469. E-mail: of Paul B. Preciado provides a useful route for the investigation and translation of [email protected] specific asignifying operations. b Professor of the Graduate Program in Communication Keywords: Asignifying semiotics, Lazzarato, Preciado, communication at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). CNPQ Productivity Scholarship RESUMO Holder. Postdoctoral fellow Este artigo aborda a distinção entre semiologia significante e semiótica assignificante, with CNPq scholarship. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002- concebida por Félix Guattari e retomada por Maurizio Lazzarato no escopo de uma 1194-6438. -

Immaterial Labor Maurizio Lazzarato

Immaterial Labor Work, Migration, Memes, Personal Geopolitics Immaterial Labor Maurizio Lazzarato A significant amount of empirical research has been conducted concerning the new forms of the organization of work. This, combined with a corresponding wealth of theoretical reflection, has made possible the identification of a new conception of what work is nowadays and what new power relations it implies. An initial synthesis of these results-framed in terms of an attempt to define the technical and subjective-political composition of the working class can be expressed in the concept of immateral labor, which is defined as the labor that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity. The concept of immaterial labor refers to two different aspects of labor. On the one hand, as regards the “informational content” of the commodity, it refers directly to the changes taking place in workers’ labor processes in big companies in the industrial and tertiary sectors, where the skills involved in direct labor are increasingly skills involving cybernetics and computer control (and horizontal and vertical communi- cation). On the other hand, as regards the activity that produces the “cultural content” of the commodity, immaterial labor involves a series of activities that are not normally recognized as “work” in other words, the kinds of activities involved in defining and fixing cultural and artistic standards, fashions, tastes, consumer norms, and, more strategically, public opinion. Once the privileged domain of the bourgeoi- sie and its children, these activities have since the end of the 1970s become the domain of what we have come to define as “mass intellectuality.” The profound changes in these strategic sectors have radically modified not only the composition, management, and regulation of the workforce–the organization of production–but also, and more deeply, the role and function of intellectuals and their activities within society. -

© 2016 Miriam Tola ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2016 Miriam Tola ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ECOLOGIES OF THE COMMON: FEMINISM AND THE POLITICS OF NATURE by MIRIAM TOLA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Women’s and Gender Studies Written under the direction of Ed Cohen and Elizabeth Grosz ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------- New Brunswick, New Jersey OCTOBER 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ECOLOGIES OF THE COMMON: FEMINISM AND THE POLITICS OF NATURE By MIRIAM TOLA Dissertation Directors: Ed Cohen, Elizabeth Grosz This dissertation proposes a theory of the common beyond the modern figure of Man as primary agent of historical transformation. Through close reading of Medieval debates on poverty and common use, contemporary political theory and political speeches, legal documents, and protests in public spaces, it complicates current debates on the common in three ways. First, this work contends that the enclosures of pre-modern landholdings, a process the unfolded in connected and yet distinct ways in Europe and the colonies, was entangled with the affirmation of the European white man as proper figure of the human entitled to appropriate the labor of women and slaves, and the material world as resources. Second, it engages contemporary theorists of the common such as Paolo Virno, Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt. Although these authors depart from the prevalent assumptions of modern liberalism (in that they do not take the individual right to appropriate nature as the foundation of political community), their formulation of common is still grounded in Marx’s view of labor as the primary force making the world. -

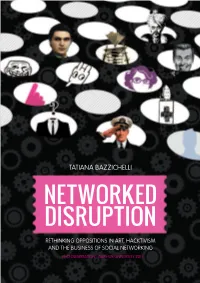

Networked Disruption Networked

NETWORKED DISRUPTION fter the emergence of Web 2.0, the critical framework of art and hacktivism has shifted from developing strategies of opposition to embarking on the art of disruption. By identifying the present Acontradictions within the economical and political framework of Web 2.0, hacker and artistic practices are analysed through business instead of in opposition to it. Connecting together disruptive practices of networked art and hacking BAZZICHELLI TATIANA TATIANA BAZZICHELLI in California and Europe, the author proposes a constellation of social networking projects that challenge the notion of power and hegemony, such as mail art, Neoism, Th e Church of the SubGenius, Luther Blissett, Anonymous, Anna Adamolo, Les Liens Invisibles, the Telekommunisten collective, Th e San Francisco Suicide Club, Th e Cacophony Society, the NETWORKED early Burning Man Festival, the NoiseBridge hackerspace, and many others. Tatiana Bazzichelli is a PhD Scholar at Aarhus University. She was a visiting scholar at Stanford University (2009) and is part of the transmediale DISRUPTION festival team in Berlin. Active in the Italian hacker community since the end of the ’90s, her project AHA won the honorary mention for digital RETHINKING OPPOSITIONS IN ART, HACKTIVISM communities at Ars Electronica in 2007. She has previously written the book Networking: Th e Net as Artwork (Costa & Nolan, 2006/DARC, AND THE BUSINESS OF SOCIAL NETWORKING 2008). www.networkingart.eu PHD DISSERTATION · AARHUS UNIVERSITY 2011 NETWORKED DISRUPTION Rethinking Oppositions in Art, Hacktivism and the Business of Social Networking Tatiana Bazzichelli PhD Dissertation Department of Information and Media Studies Aarhus University 2011 Supervisor: Søren Pold, Associate Professor Department of Information and Media Studies, Aarhus University. -

Towards an Immanent Critique of the Attention Economy

TOWARDS AN IMMANENT CRITIQUE OF THE ATTENTION ECONOMY Labour, Time, and Power in Post-Fordist Capitalism Claudio Celis Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy School of English, Communication & Philosophy Cardiff University 2015 SUMMARY This thesis develops an immanent critique of the concept of attention economy from the perspectives of labour, time, and power. The attention economy is a notion forged by authors belonging to the field of political economy in order to explain the growing value of human attention in societies characterised by post-industrial modes of production. In a world in which information and knowledge become central to the valorisation process of capital, human attention becomes a scarce and hence increasingly valuable commodity. At the same time, the attention economy turns human attention into a form of labour and hence into a new mechanism of capitalist exploitation. Using a series of contemporary readings of Marx (Postone; Lazzarato; Negri and Hardt; Deleuze and Guattari), this thesis develops a critique which does not simply apply Marxist categories to the object of the attention economy, but which uses the attention economy as a concrete object of analysis for reflecting upon both the validity and the importance of Marx‟s critique of political economy for a critique of contemporary capitalism. In other words, this research suggests that, although the attention economy has indeed turned human attention into a new form of labour, it is only through a systematic reinterpretation of Marx‟s categories that this claim can be fully grasped. This reinterpretation comprises two general aspects. Firstly, this thesis argues that the way in which the attention economy produces and exploits value puts into crisis the traditional category of labour based on an industrial mode of production and which relies solely on abstract labour time as its general equivalent. -

Maurizio Lazzarato: “Immaterial Labor”

from Paolo Virno and Michael Hardy, eds. Radical Thought In Italy: A Potential Politics Immaterial Labor Maurizio Lazzarato A significant amount of empirical research has been conducted concerning the new forms of the organization of work. This, combined with a corresponding wealth of theoretical reflection, has made possible the identification of a new conception of what work is nowadays and what new power relations it implies. An initial synthesis of these results — framed in terms of an attempt to define the technical and subjective-political composition of the working class — can be expressed in the concept of immaterial labor, which is defined as the labor that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity. The concept of immaterial labor refers to two different aspects of labor. On the one hand, as regards the "informational content" of the commodity, it refers directly to the changes taking place in workers' labor processes in big companies in the industrial and tertiary sectors, where the skills involved in direct labor are increasingly skills involving cybernetics and computer control (and horizontal and vertical communi- cation). On the other hand, as regards the activity that produces the "cultural con- tent" of the commodity, immaterial labor involves a series of activities that are not normally recognized as "work" — in other words, the kinds of activities involved in defining and fixing cultural and artistic standards, fashions, tastes, consumer norms, and, more strategically, public opinion. Once the privileged domain of the bour- geoisie and its children, these activities have since the end of the 1970s become the from Paolo Virno and Michael Hardy, eds. -

SEMIOTEXT(E) INTERVENTION SERIES © Amsterdam, 2011

r SEMIOTEXT(E) INTERVENTION SERIES © Amsterdam, 2011, Published by arrangement with Agence Iitteraire Pierre Astier & Assoch�s. This translation © 2012 by Semiotext(e} All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, elec� rconic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Cet ouvrage publie clans le cadre du programme d'aide a la publication beneficie du soutien du Ministere des Mfaires Etrangeres et du Service Culturel de l'Ambassade de France represente aux f'-tars-Unis. This work received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States through their publishing assistance program. Published by Semiotext(e) 2007 Wilshire B1vd., Suite 427, Los Angeles, CA 90057 www.semiotexte.com Thanks to John Ebert. Design: Hedi El Kholti Inside cover photograph: Michael Oblowitz ISBN: 978-1-58435-115-3 Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, England Printed in the United States of America Maurizio Lazzarato The Making of the Indebted Man An Essay on the Neoliberal Condition Translated by Joshua David Jordan Contents Foreword 7 1. Understanding Debt as the Basis of Social Life 13 2. The Genealogy of Debt and the Debtor 37 3. The Ascendency of Debt in Neoliberalism 89 Conclusion 161 Introduction to the Italian Translation 167 Notes 185 3 THE ASCENDENCY OF DEBT IN NEOLlBERALlSM FOUCAULT AND THE "BIRTH" OF NEOLlBERALlSM Debt constitutes the most deterritorialized and the most general power relation through which the neoliberal power bloc institutes its class struggle. -

The Way out Invisible Insurrections and Radical Imagi- Naries in the UK Underground 1961-1991

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The way out invisible insurrections and radical imagi- naries in the UK underground 1961-1991 https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40068/ Version: Full Version Citation: Frederiksen, Kasper Opstrup (2014) The way out invisible in- surrections and radical imaginaries in the UK underground 1961-1991. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email The Way Out Invisible Insurrections and Radical Imaginaries in the UK Underground 1961-1991 Kasper Opstrup Frederiksen PhD Humanities and Cultural Studies Birkbeck College University of London 1 Declaration of Authorship: I hereby declare that, except where explicit attribution is made, this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. ________________________________________________ Kasper Opstrup Frederiksen 2 Abstract This thesis explores a 'hidden' cultural history of experiments to engineer culture to transform humanity. Through a mixture of ideas drawn from artistic avant-garde movements as well as new social and religious movements, it examines the radical political and hedonist imaginaries of the experimental fringes of the UK Underground. Even though the theatres of operation have changed more than once since 1991 with the rise of the internet and a globalised finance economy, these imaginaries still raise questions that speak directly to the contemporary. My central inquiry examines the relations between collective practices with an explicit agenda of cultural revolution and discourses of direct revolutionary action, cultural guerrilla warfare and patchwork spirituality, all aiming to generate new forms of social life. -

1.2 Negri-Format

Antonio Negri. “The Labor of the Multitude and the Fabric of Biopolitics.” Trans. Sara Mayo, Peter Graefe and Mark Coté. Ed. Mark Coté. Mediations 23.2 (Spring 2008) 8-25. www.mediationsjournal.org/the-labor-of-the-multitude-and- the-fabric-of-biopolitics. The Labor of the Multitude and the Fabric of Biopolitics1 Antonio Negri Translated by Sara Mayo and Peter Graefe with Mark Coté Edited and Annotated by Mark Coté Editor’s Note I had the pleasure of driving Toni Negri to the McMaster University campus for his brief stay as the Hooker Distinguished Visiting Professor. As contin- gency would have it, we approached the city from the east, since I had picked him up at Brock University. Anyone familiar with Hamilton knows that this necessitates driving past the heart of “Steeltown.” Negri, in a driving practice true to his theoretical orientation, excitedly requested that we follow the route most proximal to the mills and smokestacks of Stelco and Dofasco. He asked many questions about the history of steelworkers’ labor struggles, the composition of the labor force, its level and form of organization, and the role of heavy industry in the Canadian economy. Negri’s keen interest in the conditions of a quintessentially material form of industrial production provides a necessary counterpoint to the strong poststructuralist inflection of his lecture. After all, his stated focus was on the subjective, the cultural, and the creative as key modalities of labor under globalization. These contrapuntal elements bring us to the heart of Negri’s project, wherein the conceptual deployments of Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze act as articulated elements of his longstanding and ongoing com- mitment to Marxist theory and praxis. -

The Noopolitics of Capital: Imitation and Invention in Maurizio Lazzarato

excursus three The Noopolitics of Capital: Imitation and Invention in Maurizio Lazzarato The work of Maurizio Lazzarato intersects with that of Paolo Virno and Bernard Stiegler on multiple levels. First, and perhaps most immediately, there is the understanding of the current conjuncture. Lazzarato is the author of ‘Imma- terial Labour’, an early and often criticised text, which attempted to thematise the cognitive and intellectual dimension of contemporary capitalism. In that text, Lazzarato defines immaterial labour as that which produces the inform- ational or affective dimension of a commodity.1 Like Virno and Stiegler, his understanding of the current conjuncture is framed through the intersection of knowledge and capitalism, through the labour that produces ideas, inform- ation, and knowledge. Lazzarato’s later writings have continued to examine the contemporary transformation of capital through an investigation of debt, finance, and marketing. Lazzarato’s strongest point of intersection with Stie- gler and Virno is not his investigation of the novelty of contemporary cap- italism, nor in the problem of transindividual social relations, but the fact that these two problems are necessarily related. Lazzarato’s primary point of reference for this new understanding of social relations is not, as it was for Stiegler and Virno, the work of Gilbert Simondon, but the nineteenth-century sociologist Gabriel Tarde.2 Lazzarato can thus be situated in the broader cat- egory of transindividual thinkers, grouped by the shared problematic rather