Volume 2, Issue 6 November—December 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva Letzion Goel a Tefillah for Holding It Together Daily

Uva Letzion Goel A Tefillah for Holding it Together Daily Rabbi Zvi Engel ובא לציון גואל קדושה דסדרא - A Tefilla For Holding It Together Daily Lesson 1 (Skill Level: Entry Level) Swimming Against the Undercurrent of “Each Day and Its Curse” Sota 48a Note: What The Gemara (below) calls “Kedusha d’Sidra,” is the core of “Uva Letzion” A Parting of Petition, Praise & Prom Sota 49a Congrega(on Or Torah in Skokie, IL - R. Zvi Engel Uva Letzion Goel: Holding the World Together Page1 Rashi 49a: Kedusha d’sidra [“the doxology”] - the order of kedusha was enacted so that all of Israel would be engaged in Torah study each day at least to am minimal amount, such that he reads the verses and their translation [into Aramic] and this is as if they are engaged in Torah. And since this is the tradition for students and laymen alike, and [the prayer] includes both sanctification of The Name and learning of Torah, it is precious. Also, the May His Great Name Be Blessed [i.e. Kaddish] recited following the drasha [sermon] of the teacher who delivers drashot in public each Shabbat [afternoon], they would have this tradition; and there all of the nation would gather to listen, since it is not a day of work, and there is both Torah and Sanctification of The Name. Ever wonder why we recite Ashrei a second time during Shacharit? (Hint: Ashrei is the core of the praise of Hashem required to be able to stand before Him in Tefilla) What if it is part of a “Phase II” of Shacharit in which there is a restatement—and expansion—of some of its initial, basic themes ? -

France 2016 International Religious Freedom Report

FRANCE 2016 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution and the law protect the right of individuals to choose, change, and practice their religion. The government investigated and prosecuted numerous crimes and other actions against religious groups, including anti-Semitic and anti- Muslim violence, hate speech, and vandalism. The government continued to enforce laws prohibiting face coverings in public spaces and government buildings and the wearing of “conspicuous” religious symbols at public schools, which included a ban on headscarves and Sikh turbans. The highest administrative court rejected the city of Villeneuve-Loubet’s ban on “clothes demonstrating an obvious religious affiliation worn by swimmers on public beaches.” The ban was directed at full-body swimming suits worn by some Muslim women. ISIS claimed responsibility for a terrorist attack in Nice during the July 14 French independence day celebration that killed 84 people without regard for their religious belief. President Francois Hollande condemned the attack as an act of radical Islamic terrorism. Prime Minister (PM) Manuel Valls cautioned against scapegoating Muslims or Islam for the attack by a radical extremist group. The government extended a state of emergency until July 2017. The government condemned anti- Semitic, anti-Muslim, and anti-Catholic acts and continued efforts to promote interfaith understanding through public awareness campaigns and by encouraging dialogues in schools, among local officials, police, and citizen groups. Jehovah’s Witnesses reported 19 instances in which authorities interfered with public proselytizing by their community. There were continued reports of attacks against Christians, Jews, and Muslims. The government, as well as Muslim and Jewish groups, reported the number of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents decreased by 59 percent and 58 percent respectively from the previous year to 335 anti-Semitic acts and 189 anti-Muslim acts. -

The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who Is Who? Who Is Behind It?

Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l Avenue d’Auderghem 61/16, 1040 Brussels Phone/Fax: 32 2 3456145 Email: [email protected] – Website: http://www.hrwf.eu No Entreprise: 0473.809.960 The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who is Who? Who is Behind it? By Willy Fautré The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults About the so-called experts of the Israeli Center for Victims of Cults and Yad L'Achim Rami Feller ICVC Directors Some Other So-called Experts Some Dangerous Liaisons of the Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Conclusions Annexes Brussels, 1 September 2018 The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who is Who? Who is Behind it? The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults (ICVC) is well-known in Israel for its activities against a number of religious and spiritual movements that are depicted as harmful and dangerous. Over the years, the ICVC has managed to garner easy access to the media and Israeli government due to its moral panic narratives and campaign for an anti-cult law. It is therefore not surprising that the ICVC has also emerged in Europe, in particular, on the website of FECRIS (European Federation of Centers of Research and Information on Cults and Sects), as its Israel correspondent.1 For many years, FECRIS has been heavily criticized by international human rights organizations for fomenting social hostility and hate speech towards non-mainstream religions and worldviews, usually of foreign origin, and for stigmatizing members of these groups.2 Religious studies scholars and the scientific establishment in general have also denounced FECRIS for the lack of expertise of their so-called “cult experts”. -

Digital Religion

DIGITAL RELIGION DIGITAL RELIGION Based on papers read at the conference arranged by the Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History, Åbo Akademi University, Åbo/Turku, Finland, on 13–15 June 2012 Edited by Tore Ahlbäck Editorial Assistant Björn Dahla Published by the Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History Åbo/Turku, Finland Distributed by BTJ Finland Editorial secretary Maria Vasenkari Linguistic editing Sarah Bannock ISSN 0582-3226 ISBN 978-952-12-2897-1 Printed in Finland by Vammalan kirjapaino Sastamala 2013 Editorial note he theme for our symposium 2012 was ‘Digital religion’ and in our call Tfor papers we described it in the following way: ‘ “Digital Religion’ aims to explore the complex relationship between religion and digital technologies of communication. Digital religion encompasses a myriad of connections and the goal of the conference is to approach the subject from multiple perspec- tives.’ As can be seen from the conference proceedings, we did not achieve what we aimed for. The theme was too vast. We knew as much; a new field is always difficult to handle. Despite this, we still hope that the participants got some- thing out of the conference, and we also hope that the readers of the proceed- ings will benefit from them. I wish to finish this editorial note by acknowledging my colleague Björn Dahla. For many years we organised the Donner symposia and edited the conference proceedings together. I owe him my sincere gratitude. I also want to warmly thank Maria Vasenkari who, for many years, did the necessary, extensive technical work in order to follow the conference pro- ceedings through into print. -

The Song Redemption

The Song of the Redemption Na Nach Nachma Nachman MeUman Breslev Books P.O.Box 1053 13110 Zefat , ISRAEL [email protected] The printing and distribution of this book is done with the intention of fulfilling the wishes of the holy Rabbi Yisroel Ber Odesser of blessed memory who urged us in his last will and testament to continue the work of spreading the light, wisdom and name of the holy Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, ' Rebbe Na Nach Nachma Nachman MeUman ' to every home throughout the world. May the final redemption be hastened through this work. Cover Art by Saba-Noon [email protected] sponsored by New Outreach Project www.newoutreach.com For more information in english, visit us: "The Na Nach Center 77 Jerusalem St. Tzfat" www .nanach.net Rabbi Israel Dov-Ber Odesser I am Na Nach Nachma Nachman Meuman The Song of the Redemption An Exposition of " Na Nach Nachma Nachman Meuman ", the Petek, and the Message of Rabbi Israel Ber Odesser Dedicated to Our Master and Teacher, may his merit protect us, Rabbi Israel Dov-Ber Odesser who said: " I am Na Nach Nachma Nachman Meuman " and who said: "G-d may He be blessed, knows and will attest that I am ready and willing, to give my life, my money and all that I own, in order to draw even one Jewish soul to G-d, or in any case, to instill in him some thought of repentance, even for just one moment." Published through the Foundation "Le Chant d'Israèl" In cooperation with the "Keren Anachal Foundation" On the Internet: www.moharan.com Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................... -

Thecultphenomenonhowgroup

Authors: Mike Kropveld Executive Director Info-Cult Marie-Andrée Pelland Doctoral Student in Criminology Université de Montréal Translated by: Natasha DeCruz Gwendolyn Schulman Linguistic Landscapes Cover Design by: Philippe Lamoureux This book was made possible through the financial support of the Ministère des Relations avec les citoyens et de l'Immigration. However, the opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. The translation from the French version (Le phénomène des sectes: L’étude du fonctionnement des groupes ©2003) into English was made possible through the financial support of Canadian Heritage. ©Info-Cult 2006 ISBN: 2-9808258-1-6 The Cult Phenomenon: How Groups Function ii Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................... ii Preface .......................................................................................................................viii Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: History of Info-Cult.......................................................................................3 Cult Project................................................................................................................3 Description.............................................................................................................3 Cult Project’s objectives.........................................................................................4 -

Cults and Psychological Manipulation

WORKSHOP FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS: PSYCHOLOGICAL MANIPULATION, CULTS AND CULTIC RELATIONSHIPS 1. What is a destructive cult? Langone’s definition Singer’s Continuum of Influence and Persuasion 2. Do people join cultic groups? Factors that increase vulnerability Cult Recruitment: One Predictable Factor 3. Overview of Thought Reform: Four models 4. Singer’s Conditions for Thought Reform (Explore how each condition applies to the client’s group) 5. Assessment of current and former group members Screening tools Motivation for seeking therapy Clinical picture of cult survivors Post Group Distress Most typical cult induced psychopathologies PTSD/Complex PTSD 6. Assessment of cult as well as cult leader Evaluate client’s safety while inquiring about the cult and its leadership Discuss possible psychopathology of the cult leader 7. Treatment of current cult members 8. Treatment of former members: First and Second Generation Stages of Recovery: Therapeutic goals Recommendations for Therapists 9. Types of care and reliable resources Prepared by: Rosanne Henry, LPC www.CultRecover.com I WHAT IS A DESTRUCTIVE CULT? A destructive cult is a group or movement that, to a significant degree xhibits great or excessive devotion or dedicationto some person, idea, or thing Uses a thought-reform program to persuade, control, and socialize members Systematically induces states of psychological dependency in members Exploits members to advance the leadership’s goals, and Causes psychological harm to members, their families, and the community. Langone, M.D. (Ed.). (1993) Recovery from Cults: Help for Victims of Psychological and Spiritual Abuse. New York: W. Norton & Company. SINGER’S CONTINUUM OF INFLUENCE AND PERSUASION Singer, M.T. -

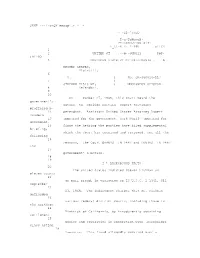

ENT ~~~'~Orqx Eecop~.R ~ * ~ ~Z2~'

$ENT ~~~'~orQX eecop~.r ~ * ~ ~Z2~'aVED T~u~TcHcouN~ PF~OSECUT~NG A1T~ L_t\~R Z~ 1~99O eIICD 1 2 UNITED ST .~~d~~oURu1r PbP~ )A1~9O 3 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA ~ W UNITED STATES, Plaintiff, 6 v. ) No. cR-S60616-DL7 7 ) STEPHEN 71510 WI, ) MMORaNDUX OPIUZON 8 Defendant. 9 10 On camber 27, 1969, this Court heard the government's motion to exclude certain expert testimony proffered b~ 12 defendant. Assistant United States Attorney Robert Dondero IS appeared for the government. Hark Nuri3~ appeared for defendant. 14 Since the hearing the partiem have filed supplemental briefing, which the Court has received and reviewed. For all the following 16 reasons, the Court GRANTS IN PART and DENIES IN PART the 17 government' a motion. 18 19 I * BACKGROUND FACTS 20 The United States indicted Steven ?iuhman on eleven counts 21 of mail fraud, in violation of IS U.S.C. 1 1341, 011 September 22 23, 1968. The indictment charges that Xr. Fishman defrauded 23 various federal district courts, including those in the Northern 24 District of California, by fraudulently obtaining settlement 25 monies and securities in connection with .hareholder class action 28 lawsuits. This fraud allegedly occurred over a lengthy period 27 of time -~ from September 1963 to Nay 1958. 28 <<< Page 1 >>> SENT ~y;~grox ~ ~ * Two months after his indictment, defendant notified this 2 Court of his intent to rely on an insanity defense, pursuant to Rule 12.2 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. Within the context of his insanity defense, defendant seeks to present 5 evidence that influence techniques, or brainwashing, practiced 8 upon him by the Church of Scientology ("the Church") warn a cause of his state of mind at the tim. -

France Page 1 of 8

France Page 1 of 8 France International Religious Freedom Report 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respected this right in practice; however, some religious groups remain concerned about legislation passed in 2001 and 2004, which provided for the dissolution of groups under certain circumstances and banned the wearing of conspicuous religious symbols by public school employees and students. A 1905 law on the separation of religion and state prohibits discrimination on the basis of faith. Government policy continued to contribute to the generally free practice of religion. A law prohibiting the wearing of conspicuous religious symbols in public schools by employees and students entered into force in September 2004. Despite significant efforts by the Government to combat anti-Semitism and an overall decline in the number of incidents, anti-Semitic attacks persisted. The Government has a stated policy of monitoring potentially "dangerous" cult activity through the Inter-ministerial Monitoring Mission against Sectarian Abuses (MIVILUDES). Some groups expressed concern that MIVILUDES publications contributed to public mistrust of minority religions, and that public statements from the new president indicated the organization would take a harder line against minority religions. The UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief issued a report indicating that the Government generally respected the right to freedom of religion or belief, but expressed concern about the application of the 1905 law, the treatment of cult groups and certain new religious movements, and the 2004 legislation regarding religious symbols in schools. The generally amicable relationship among religious groups in society contributed to freedom of religion. -

Matot-Maasei Copy.Pages

BS”D South Head Youth Parasha Sheet Parashat Matot Parashat Matot teaches us the importance of our words. One might think that the words we speak are not important. However, this is not so. The Torah teaches us that words are very important. A Jew should be careful with the words he uses, particularly when making a promise. This is because when we make a promise we are responsible to keep it. For this reason, it is actually best to avoid making promises, because when a person breaks his promise he has committed a sin. Therefore, rather than making a promise, it’s a good idea to say the words ‘Bli Neder'. These words translate to mean ‘it’s not a promise’. So when a person says that he is going to do something, and adds in the words ‘Bli Neder’ he is not bound by any promises. Therefore, if he forgets to do what he said he was going to do, the person has not committed a sin. Of course, there is the off-chance that we might forget to say the words ‘Bli Neder’ and we might actually promise to do something which for some reason we do not end up doing. Therefore the Torah teaches us a few ways of undoing a promise. A person may go to a Beit Din, a Jewish Court or to a great Torah scholar and explain to the Beit Din or the Torah scholar the promise he made. The Beit Din or Torah scholar can then nullify the promise for the person if they find a good reason to cancel it. -

Cults and Families

REVIEW ARTICLES Cults and Families Doni Whitsett & Stephen A. Kent Abstract This article provides an overview of cult-related issues that may reveal themselves in therapeutic situations. These issues include: families in cults; parental (especially mothers’) roles in cults; the impact that cult leaders have on families; the destruction of family intimacy; child abuse; issues encountered by noncustodial parents; the impact on cognitive, psychological, and moral development; and health issues. The authors borrow from numerous the- oretical perspectives to illustrate their points, including self psychology, developmental theory, and the sociology of religion. They conclude with a discussion of the therapeutic challenges that therapists face when working with cult-involved clients and make preliminary recommendations for treatment. FOR MOST INDIVIDUALS, it is mysterious and beyond Colloquium: Alternative Religions: Government control their comprehension how intelligent people can get caught and the first amendment, 1980) and the near sacrosanct up in often bizarre (and sometimes dangerous) cults.1 Yet a value of family autonomy. In addition, professional uncer- remarkable number of people do, as contemporary cults tar- tainty about proper counseling responses to clients’ disclo- get individuals throughout their life spans and across all sures of previous or current cult involvement stems from socioeconomic brackets and ethnicities. Regrettably, it is insufficient knowledge of the various cognitive, emotional, impossible to quantify how many people are involved in and behavioral indicators that are associated with member- potentially damaging cultic religions or similar ideological ship in highly restrictive groups. commitments, but one estimate of prior involvement comes By this time in the development of the profession, most from Michael Langone—a psychologist who is the executive clinicians routinely assess for evidence of domestic violence director of the American Family Foundation (a respected or child abuse. -

Nachman Ben Simcha, Keren Rabbi Israel Dov Odesser, 2007, 097976551X, 9780979765513

The Book of Traits (Sefer HaMidot)., Nachman ben Simcha, Keren Rabbi Israel Dov Odesser, 2007, 097976551X, 9780979765513, . DOWNLOAD HERE Rabbi Nachman's Tikkun , Naбёҕman (of Bratslav), Avraham Greenbaum, Avraham Weitzhandler, Nathan Sternharz, 1984, Religion, 240 pages. Depression is one of the greatest problems facing contemporary man. It stems from man's abuse of his God-given powers. The Ten Psalms making up Rebbe Nachman's Tikkun -- a .... Liбёіuṕe Moharan, Volume 6 , Naбёҕman (of Bratslav), Chaim Kramer, 1999, Religion, 433 pages. Inner Rhythms The Kabbalah of Music, DovBer Pinson, 2000, Music, 179 pages. What is Jewish Music? What makes a song "sound Jewish?" What is the place of music in Jewish history and philosophy? The author writes, "What is known to us as Jewish music is .... Breslov (also Bratslav, also spelled Breslev) is a branch of Hasidic Judaism founded by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810) a great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidism. Its adherents strive to develop an intense, joyous relationship with God and receive guidance toward this goal from the teachings of Rebbe Nachman. The movement has had no central, living leader for the past 200 years, as Rebbe Nachman did not designate a successor. As such, they are sometimes referred to as the טויטע חסידיו (the "Dead Hasidim"), since they have never had another formal Rebbe since Nachman's death. However, certain groups and communities under the Breslov banner refer to their leaders as "Rebbe". The movement weathered strong opposition from virtually all other Hasidic movements in Ukraine throughout the nineteenth century, yet at the same time experienced tremendous growth in numbers of followers from Ukraine, White Russia, Lithuania and Poland.