An Open Access Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leicester and Birmingham

Leicester and Birmingham Two purpose built freehold supermarket Investments let to Iceland with 11 years unexpired and a fixed rental uplift in 2025 and significant future development potential Two purpose built freehold supermarket Investments let to Iceland for 11 years Leicester and Birmingham unexpired with fixed uplifts in 2025 and significant future development potential The Opportunity n Two prime freehold supermarket investments in Leicester and Birmingham totalling 15,725 sq ft n Purpose built units constructed in Iceland’s iconic building design n Each property is located in popular residential areas close to the City Centre with significant future development potential (STC) n Fully let to Iceland Foods Limited for 11 years unbroken guaranteed by Iceland Topoco Limited until 2030 n Large cumulative site area of approximately 1 acre (0.4 ha) n Total passing rent of £184,476 pa with a guaranteed fixed uplift in 2025 to £208,718 pa n Opportunity to buy both properties together or on an individual basis n Offers to purchase both properties are sought in excess of £3,465,000 (Three Million Four Hundred and Sixty Five Thousand Pounds) subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. This reflects a blended net initial yield of 5% and a reversionary yield of 5.68% after allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.50%. Summary Schedule Property Area Sq ft Area Sq m Rent £ psf 2025 rental uplift 197-201 Narborough Road, Leicester 7,046 654.58 £94,953 pa £13.57 £107,431 pa 577 Kingstanding Road, Birmingham 8,679 806 £89,523 pa £10.30 £101,287 pa Total -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

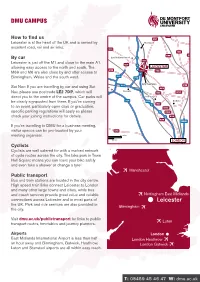

DMU CAMPUS A46 Nottingham

A17 DMU CAMPUS A46 Nottingham A50 How to find us A15 A1 A16 Leicester is at the heart of the UK and is served by East Midlands Airport 24 excellent road, rail and air links. A46 A42 22 21a By car A5 A5460 A47 21 M42 Leicester is just off the M1 and close to the main A1, M69 allowing easy access to the north and south. The City Campus M69 and M6 are also close by and offer access to M6 A1 Birmingham A6 Birmingham, Wales and the south west. Coventry 19 M42 A14 A605 Northampton Sat Nav: If you are travelling by car and using Sat Nav, M40 M1 Bedford please use postcode LE2 7DP, which will direct you 15 A45 A422 to the centre of the campus. Car parks will be clearly 14 A421 signposted from there. If you’re coming to an event, 13 A6 A5 particularly open days or graduation, specific parking A1(M) regulations will apply so please check your joining instructions for details. A40 0 20 miles If you’re travelling to DMU for a business meeting, 0 20 km visitor spaces can be pre-booked by your meeting organiser. Cyclists Cyclists are well catered for with a marked network of cycle routes across the city. The bike park in Town Manchester Hall Square means you can leave your bike safely and even take a shower or change a tyre! Public transport Bus and train stations are located in the city centre. Nottingham East Midlands High speed train links connect Leicester to London Leicester and many other large towns and cities, while bus Birmingham and coach services provide great value and reliable connections across Leicester and to most parts of the UK. -

160512 TLANG Presentation

MIGRANT LIVELIHOODS Transaction Economies in Birmingham and Leicester Suzanne Hall, LSE Cities TLANG Network Assembly, Birmingham, May 2016 Manchester Leicester Birmingham Bristol Concentration and dispersal across by birth outside UK (ONS, 2011) (2011 ONS Metropolitan % Born Ethnic Census) Boroughs outside UK minority pop. London 8,416,535 41.6% 40.48% Birmingham 1,074,300 22.9% 36.74% Manchester 502,900 26.7% 30.07% (2,682,500) Bristol 442,500 14.7% 22.1% Leicester 333,800 33.6% 49.4% (Multiple Sources) Rookery Road to World, by Place of Origin (Super-diverse Streets 2015, Julia King) Narborough Road to World, by Place of Origin (Super-diverse Streets 2015, Julia King) Survey Summary (Super-diverse Streets 2015, Julia King) Rookery Road, Birmingham Rookery Road to World, by Place of Origin (Super-diverse Streets 2015, Julia King) Migrant Sedimentation Rana: My parents came to Birmingham from the Punjab in the 1960s. They were invited by the British Government. (Fieldwork Interview 2015) (Image: Billy Dosanjh, Black Country Echoes, http://www.blackcountryechoes.org.uk/) Gurdwara, Rookery Road (Image: https://plus.google.com/+GurdwaraBebeNanakiji/posts) (Image: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/gurdwarasturnedfood-banks-sikh-temples- are-catering-for-rise-in-britains-hungry-8991824.html) Aasin: Since 2010, the funding is no longer there. ….programmes, which were free, have been outsourced to training and certifying agencies ... (Fieldwork interview, 2015). Rookery Road, Birmingham Narborough Road, Leicester Migrant Churn Jack: What’s really significant here is the churn – it’s a very, very transient population. (Fieldwork Interview 2015) (Image: https://www.google.co.uk/maps 2015) Narborough Road : Unit types and duration on street. -

Campus Map Update 2016

DMU CAMPUS A17 How to find us A46 Leicester is at the heart of the UK and is served by Nottingham excellent road, rail and air links. A50 A15 A1 A16 By car East Midlands Airport 24 Leicester is just off the M1 and close to the main A1, A46 A42 22 allowing easy access to the north and south. The 21a A5 A5460 A47 M69 and M6 are also close by and offer access to 21 M42 Birmingham, Wales and the south west. M69 City Campus M6 A1 Sat Nav: If you are travelling by car and using Sat Birmingham A6 Coventry 19 Nav, please use postcode LE2 7DP, which will M42 A14 A605 direct you to the centre of the campus. Car parks will Northampton be clearly signposted from there. If you’re coming M40 M1 Bedford 15 A45 to an event, particularly open days or graduation, A422 specific parking regulations will apply so please 14 A421 check your joining instructions for details. 13 A6 A5 A1(M) If you’re travelling to DMU for a business meeting, visitor spaces can be pre-booked by your A40 meeting organiser. 0 20 miles 0 20 km Cyclists Cyclists are well catered for with a marked network of cycle routes across the city. The bike park in Town Hall Square means you can leave your bike safely and even take a shower or change a tyre! Manc hester Public transport Bus and train stations are located in the city centre. High speed train links connect Leicester to London and many other large towns and cities, while bus and coach services provide great value and reliable Nottingham East Midlands connections across Leicester and to most parts of Leicester the UK. -

Permit Holders Register

Permit Holders Register The Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2016 Part A2 and Part B installations regulated for pollution prevention and control 2 May 2019 There have been no enforcement notices served on any permitted installation within the time period 22 August 2013 to present day ACTIVE PERMITS Registered Office Company Address City & Postcode Permit Ref Grid Reference Date of issue SGN / PGN Address Part A1 Processes Local Authorities are not responsible for regulating Part A(1) industrial permitted processes. For more information contact the Environment Agency Part A2 Processes Coating Borland Avenue Golf Course Lane Botcherby Crown Bevcan Leicester, LE3 1TX IPPC A202/CP SK5452 0396 04/08/1993 SG6 (11) Braunstone Carlisle CA1 2TL Non-ferrous metals Braunstone Frith Ind. Est. Norman and Underwood Ltd Leicester, LE3 1UQ As installation IPPC A203/NU 453552/304277 13/06/2005 SG4 (06) 170 Scudamore Road Part B Processes Car Spraying GEMINI HOUSE ADR Accident Repair Ltd T/A Gemini STOURPORT ROAD 180 Waterside Road Leicester, LE5 1QZ 080 462435, 307728 19/06/1995 PG 6/34 (11) Accident Repair Centres KIDDERMINSTER DY11 7QL Chawda Motors 90 Osmaston Road Leicester, LE5 5JG As installation 159 460589, 303565 05/02/2013 PG 6/34 (11) Drive Vauxhall Leicester Freemen’s Common Road Leicester, LE2 7QN As installation 041 458608,302716 21/09/1993 PG 6/34 (11) MERUS COURT Harlequin Motors Unit 12, Lunsford Road Leicester, LE5 0HJ 109 460547, 305840 15/08/2003 PG 6/34 (11) 2 MERUS COURT Registered Office Company Address City -

The Leicestershire Archjeological and Historical Society 1961-2

THE LEICESTERSHIRE ARCHJEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1961-2 President Lieut.-Col. Sir Robert Martin, C.M.G., D.L., T .D., LLD., M.A. (Deceased 13 1une 1961) Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., C.B.E., M.C., M .A., F.S.A. (Elected 29 September 1961) * Vice-Presidents Kathleen, Duchess of Rutland The Hon. Lady Martin The Right Revd. The Lord Bishop of Leicester, D.D. The High Sheriff of Leicestershire The Right Worshipful The Lord Mayor of Leicester The Very Revd. H. A. Jones,, B.Sc., Dean of Manchester Albert Herbert, Esq., F.R.I.B.A., F.S.A. Victor Po:::hin, Esq., C.B.E., M.A., D.L., J.P. A. Bernard Clarke, Esq. Levi Fox, Esq., M.A., F.S.A. W. G. Hoskins, Esq., M.A., Ph.D. Miss K. M. Kenyon, C.B.E., M.A., D.Lit., F.B.A., F.S.A. * Officers Hon. Secretary: David T-D. Clarke, Esq., M.A., F.M.A. Hon. Treasurer: C. L. Wykes, Esq., F.C.A. Hon. Auditor: Lieut.-Col. G. L. Aspell, T.D., D.L., F.C.A. Hon. Editor : Professor J. Simmons, M .A., F.R.Hist.S., F.R.S.L. Hon. Librarian: G. H. Martin, Esq., M.A., D.Phil., F.R.Hist.S. * Trustees of the Leicestershire Archawlogical and Historical Society J. E. Brownlow, Esq. Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., C.B.E., M.C., M.A., F.S.A. Albert Herbert, Esq., F .R.I.B.A., F.S.A. J. N. Pickard, Esq., J.P. -

Cheetham Hill, Manchester

City Street Data Profile on Ethnicity, Economy and Migration Cheetham Hill, Manchester By Suzanne Hall, Julia King and Robin Finlay December 2015 This data emerges from an ESRC funded project on Super-diverse Streets: Economies and spaces of urban migration in UK cities (ES/L009560/1) This project is hosted by LSE Cities in the Department of Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Preface Phase 1, ‘Super-diverse streets’ data profiles, 2015 The ‘Super-diverse streets’ project is an ESRC-funded research exploration of the intersections between city streets, ethnic diversity and economic adaptations in the context of accelerated migration (ref: ES/L009560/1). The research is based on a comparative analysis across UK cities and aims to explore how urban retail economies and spaces are shaped by and shape migrant practices. The first phase of this project incorporates a qualitative survey conducted in 2015, and focuses on four ‘super-diverse’ high streets: Rookery Road (Birmingham); Stapleton Road (Bristol); Narborough Road (Leicester); and Cheetham Hill (Manchester). Each street was selected for its location in an ethnically diverse as well as comparatively deprived urban locale. Furthermore, Birmingham, Bristol, Leicester and Manchester are amongst the UK cities that have the highest percentage of ‘country of birth’ citizens from outside of the UK, after London. From this grounded perspective we trace emerging capacities as well as old and new inequalities. We also record the diversification of bodies, spaces and micro-economic networks in a world that is increasingly mobile and bordered. In total, the face-to-face surveys across four streets incorporate 910 units, 596 units include retail, service and civic activities of which 480 are retail units and 68 units were vacant. -

The Future of Towns, but Looks to Go of the Places They Live Should Look Like

THE FUTURE OF T WNS HARRY CARR BEN GLOVER STANLEY PHILLIPSON-BROWN JOSH SMITH MARK ESSEX STUART BURT DECEMBER 2020 Open Access. Some rights reserved. Open Access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos wants to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written permission. This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons By Share Alike licence. The main conditions are: • Demos and the author(s) are credited including our web address www.demos.co.uk • If you use our work, you share the results under a similar licence A full copy of the licence can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/3.0/legalcode You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence. Demos gratefully acknowledges the work of Creative Commons in inspiring our approach to copyright. To find out more go to www.creativecommons.org This project is supported by KPMG Published by Demos December 2020 © Demos. Some rights reserved. 15 Whitehall, London, SW1A 2DD T: 020 3878 3955 [email protected] www.demos.co.uk CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PAGE 4 FOREWORD PAGE 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PAGE 6 CHAPTER 1 PAGE 9 DIFFERENT TOWNS FACE DIFFERENT PROBLEMS CHAPTER 2 PAGE 18 WHAT DO WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT OUR TOWNS? CHAPTER 3 PAGE 26 WHAT -

4925 Campus Map Update-July 20192

A17 DMU CAMPUS A46 Nottingham A50 How to find us A15 A1 A16 Leicester is at the heart of the UK and is served by East Midlands Airport 24 excellent road, rail and air links. A46 A42 22 21a By car A5 A5460 A47 21 M42 Leicester is just off the M1 and close to the main A1, M69 allowing easy access to the north and south. The City Campus M69 and M6 are also close by and offer access to M6 A1 Birmingham A6 Birmingham, Wales and the south west. Coventry 19 M42 A14 A605 Northampton Sat Nav: If you are travelling by car and using Sat Nav, M40 M1 Bedford please use postcode LE2 7DP, which will direct you 15 A45 A422 to the centre of the campus. Car parks will be clearly 14 A421 signposted from there. If you’re coming to an event, 13 A6 A5 particularly open days or graduation, specific parking A1(M) regulations will apply so please check your joining instructions for details. A40 0 20 miles If you’re travelling to DMU for a business 0 20 km meeting, visitor spaces can be pre-booked by your meeting organiser. Cyclists Cyclists are well catered for with a marked network of cycle routes across the city. The bike park in Town Manchester Hall Square means you can leave your bike safely and even take a shower or change a tyre! Public transport Bus and train stations are located in the city centre. Nottingham East Midlands High speed train links connect Leicester to London Leicester and many other large towns and cities, while bus Birmingham and coach services provide great value and reliable connections across Leicester and to most parts of the UK. -

Narborough Road, Leicester

City Street Data Profile on Ethnicity, Economy and Migration Narborough Road, Leicester By Suzanne Hall, Julia King and Robin Finlay December 2015 This data emerges from an ESRC funded project on Super-diverse Streets: Economies and spaces of urban migration in UK cities (ES/L009560/1) This project is hosted by LSE Cities in the Department of Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Preface Phase 1, ‘Super-diverse streets’ data profiles, 2015 The ‘Super-diverse streets’ project is an ESRC-funded research exploration of the intersections between city streets, ethnic diversity and economic adaptations in the context of accelerated migration (ref: ES/L009560/1). The research is based on a comparative analysis across UK cities and aims to explore how urban retail economies and spaces are shaped by and shape migrant practices. The first phase of this project incorporates a qualitative survey conducted in 2015, and focuses on four ‘super-diverse’ high streets: Rookery Road (Birmingham); Stapleton Road (Bristol); Narborough Road (Leicester); and Cheetham Hill (Manchester). Each street was selected for its location in an ethnically diverse as well as comparatively deprived urban locale. Furthermore, Birmingham, Bristol, Leicester and Manchester are amongst the UK cities that have the highest percentage of ‘country of birth’ citizens from outside of the UK, after London. From this grounded perspective we trace emerging capacities as well as old and new inequalities. We also record the diversification of bodies, spaces and micro-economic networks in a world that is increasingly mobile and bordered. In total, the face-to-face surveys across four streets incorporate 910 units, 596 units include retail, service and civic activities of which 480 are retail units and 68 units were vacant. -

Participation and Advocacy in Community Media

Participation and Advocacy in Community Media By Robert Watson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, De Montfort University, September 2017 Participation and Advocacy in Community Media Robert Watson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, De Montfort University, September 2017. Abstract Community media is less well funded, supported and researched than other forms of media, and yet it holds considerable potential as a transformative experience and as an agent for social change. This thesis explores how the process of participation in community media represents an opportunity for reinvigorated democratic and civic conversations about issues of concern to local communities, par- ticularly in relation to the idea of participation and advocacy. This thesis contests mainstream media studies discourse by asserting that it is in paying attention to the lived experience and the accomplishments of people acting in lifeworlds and intimate social net- works, rather than simply looking at texts, legal frameworks and institutions, that it is possible to de- velop a wider understanding of changes in media and digital media production situations, particu- larly those defined by notions of participation, activism and agency. The study uses an ethnographically-informed mixed-methods design that incorporates participant observation, interviews and reflexive engagement. It is founded on principles of pragmatically in- formed symbolic interactionism, which suggest that it is possible to attend to the unfolding of hu- man actions and understandings as they are accomplished in the collective expression of community life that are shaped by neutral social processes. This thesis therefore contributes to an underdeveloped area of media analysis, signalling opportuni- ties for further study and evaluation of the developments of community media at a time of signifi- cant change and social reorientation.