35 Perception of Regional Dialects in Animated Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(TMIIIP) Paid Projects Through August 31, 2020 Report Created 9/29/2020

Texas Moving Image Industry Incentive Program (TMIIIP) Paid Projects through August 31, 2020 Report Created 9/29/2020 Company Project Classification Grant Amount In-State Spending Date Paid Texas Jobs Electronic Arts Inc. SWTOR 24 Video Game $ 212,241.78 $ 2,122,417.76 8/19/2020 26 Tasmanian Devil LLC Tasmanian Devil Feature Film $ 19,507.74 $ 260,103.23 8/18/2020 61 Tool of North America LLC Dick's Sporting Goods - DecembeCommercial $ 25,660.00 $ 342,133.35 8/11/2020 53 Powerhouse Animation Studios, In Seis Manos (S01) Television $ 155,480.72 $ 1,554,807.21 8/10/2020 45 FlipNMove Productions Inc. Texas Flip N Move Season 7 Reality Television $ 603,570.00 $ 4,828,560.00 8/6/2020 519 FlipNMove Productions Inc. Texas Flip N Move Season 8 (13 E Reality Television $ 305,447.00 $ 2,443,576.00 8/6/2020 293 Nametag Films Dallas County Community CollegeCommercial $ 14,800.28 $ 296,005.60 8/4/2020 92 The Lost Husband, LLC The Lost Husband Feature Film $ 252,067.71 $ 2,016,541.67 8/3/2020 325 Armature Studio LLC Scramble Video Game $ 33,603.20 $ 672,063.91 8/3/2020 19 Daisy Cutter, LLC Hobby Lobby Christmas 2019 Commercial $ 10,229.82 $ 136,397.63 7/31/2020 31 TVM Productions, Inc. Queen Of The South - Season 2 Television $ 4,059,348.19 $ 18,041,547.51 5/1/2020 1353 Boss Fight Entertainment, Inc Zombie Boss Video Game $ 268,650.81 $ 2,149,206.51 4/30/2020 17 FlipNMove Productions Inc. -

Awards & Nominations

VICKI HIATT MUSIC SUPERVISOR / EDITOR AWARDS & NOMINATIONS GOLDEN REEL AWARD ALI NOMINATION (2001) Best Sound Editing -Music, Feature Film, Domestic and Foreign GOLDEN REEL AWARD THE ROAD TO EL DORADO NOMINATION (2000) Best Sound Editing-Music, Animation FEATURE FILM THE ARK & THE AARDVARK Keith Kjarvak, Kurt Rauer, prod. Unified Pictures John Stevenson, dir. Music Editor HOTEL TRANSYLVANIA 3 Michelle Murdocca, prod. Sony Pictures Animation Gendy Tartakovsy, dir. Music Editor SURF’S UP 2: WAVEMANIA Toby Chu, Composer Sony Pictures Animation Michelle Wong, prod. Music Editor Henry Wu, dir. HALF MAGIC Alex Wurman, Composer Magic Bubble Productions Bill Sheinberg, prod. Music Consultant Heather Graham, dir. HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON 3 John Powell, Composer DreamWorks Animation Bonnie Arnold, prod. Music Editor Dean DeBlois, dir. LIFE BRIEFLY Tom Howe, Composer Thousand Dream Prods. Erika Armin, James Brubaker, prods. Music Editor Dan Ireland, dir. EMOJI Michelle Raimo, prod. Sony Pictures Animation Anthony Leondis, dir. Music Editor BOSS BABY Denise Nolan Cascino, Ramsey Ann Naito, prods. DreamWorks Animation Tom McGrath, dir. Music Editor The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 VICKI HIATT MUSIC SUPERVISOR / EDITOR INDISCRETION Toby Chu, Composer Granfallon Productions Alexandra Baranska, Thomas Beach, Laura Boersma, prods. Music Supervisor John Stewart Muller, dir. SO B. IT Nick Urata, Composer Branded Pictures J. Todd Harris, Orien Richman, prods. Music Supervisor Stephen Gyllenhaal, dir. CAPTAIN UNDERPANTS Teddy Shapiro, Composer DreamWorks Animation Mark Swift, prod. Music Editor David Soren, dir. TROLLS Christophe Beck, Composer DreamWorks Animation Gina Shay, prod. Music Editor Mike Mitchell, dir. FLAWED DOGS Berkeley Breathed, exec. prod. DreamWorks Animation Noah Baumbauch, dir. -

Seawood Village Movies

Seawood Village Movies No. Film Name 1155 DVD 9 1184 DVD 21 1015 DVD 300 348 DVD 1408 172 DVD 2012 704 DVD 10 Years 1175 DVD 10,000 BC 1119 DVD 101 Dalmations 1117 DVD 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 DVD 12 Rounds 843 DVD 127 Hours 446 DVD 13 Going on 30 474 DVD 17 Again 523 DVD 2 Days In New York 208 DVD 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 DVD 21 Jump Street 1145 DVD 27 Dresses 1079 DVD 3:10 to Yuma 1124 DVD 30 Days of Night 204 DVD 40 Year Old Virgin 1101 DVD 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 DVD 50 First Dates 117 DVD 6 Souls 1205 DVD 88 Minutes 177 DVD A Beautiful Mind 643 DVD A Bug's Life 255 DVD A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 DVD A Christmas Carol 581 DVD A Christmas Story 506 DVD A Good Day to Die Hard 212 DVD A Knights Tale 848 DVD A League of Their Own 856 DVD A Little Bit of Heaven 1053 DVD A Mighty Heart 961 DVD A Thousand Words 1139 DVD A Turtle's Tale: Sammy's Adventure 376 DVD Abduction 540 DVD About Schmidt 1108 DVD Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 1160 DVD Across the Universe 812 DVD Act of Valor 819 DVD Adams Family & Adams Family Values 724 DVD Admission 519 DVD Adventureland 83 DVD Adventures in Zambezia 745 DVD Aeon Flux 585 DVD Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 DVD Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 496 DVD Alex & Emma 79 DVD Alex Cross 947 DVD Ali 1004 DVD Alice in Wonderland 525 DVD Alice in Wonderland - Animated 838 DVD Aliens in the Attic 1034 DVD All About Steve 1103 DVD Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 785 DVD Alpha and Omega 970 DVD Alpha Dog 522 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked -

Make.Believe (メイク・ドット・ビリーブ)は、 ソニーグループの

make.believe(メイク・ドット・ビリーブ)は、 ソニーグループのブランドメッセージです。 make.believeはソニーブランドの精神を象徴しています。ソニーが持つ創造する力、 アイディアを実現する力、創る力を信じ、夢を実現するという信念を表しています。 世界中のあらゆる場所で、言葉や文化の違いをも超え、映画、音楽、ゲーム、携帯電話、 そしてエレクトロニクス商品を通じて、ソニーは新しい体験を提供しつづけています。 テクノロジーとコンテンツのユニークな組み合わせ 行動 精神 を通じ、ソニーは、その革新性と楽しさで世界中の 実行する 考える 創る 想像する お客さまに感動を与えることを目指します。 形にする 夢見る お客さまと一緒にmake.believeを通じて、夢を現実 に変えていきたいと考えています。 「.(ドット)」 “make”と“believe”を結びつけるソニーの役割 目次 財務ハイライト 2 株主の皆さまへ 4 特集:ソニーが描く3Dの世界 14 特集:急拡大する電子書籍市場 18 ビジネス概要 20 主要ビジネスの営業概況 22 取締役・執行役 44 財務セクション 45 株式情報 58 投資家メモ 59 ソニーの詳細な財務情報、コーポレートガバナンス、CSR、金融ビジネスについては、以下のサイトに掲載 しております。 2009年度 有価証券報告書 http://www.sony.co.jp/SonyInfo/IR/library/yu.html コーポレートガバナンス体制 http://www.sony.co.jp/SonyInfo/IR/info/strategy/governance.html CSRレポート http://www.sony.co.jp/SonyInfo/csr/index.html 金融ビジネス http://www.sonyfh.co.jp/index.html (ソニーフィナンシャルホールディングス(株)) 1 財務ハイライト 2009年度連結業績 (2010年3月31日に終了した1年間) 売上高および営業収入 7兆2,140 億円 ( -6.7%) 営業利益 318 億円 ( ̶ ) 税引前利益 269 億円 ( ̶ ) 当社株主に帰属する当期純損失 408 億円 ( ̶ ) *( )は前年度比 ビジネス別売上高構成比 *1 ネットワークプロダクツ&サービス 0.8% コンスーマープロダクツ&デバイス 3.6% テ レ ビ( 34%) ゲ ー ム( 56%) 11.6% 7.1% デジタル 2009年度 40.5% イ メ ー ジ ン グ( 23%) 9.8% オ ー デ ィ オ・ P C・そ の 他 5.6% ビ デ オ( 17%) ネットワ ー ク 半導体(10%) ビ ジ ネ ス( 44%) 21.0% コ ン ポ ー ネ ン ト( 16%) コンスーマープロダクツ&デバイス 音楽 ネットワークプロダクツ&サービス 金融 B2B & ディスク製造 その他 映画 全社(共通) ● 営業損益は、前年度の損失から黒字転換し、当年度は318 億円の利益を計上しました。 ● 金融分野および液晶テレビを含むコンスーマープロダクツ&デバイス分野が損益改善に寄与しました。 ● 金融分野を除く営業活動および投資活動による連結キャッシュ・フローの合計は3,000億円 以上のポジティブとなりました。*2 *1 外部顧客に対する売上高および営業収入にもとづく比率 *2 これらの情報は米国会計原則に則って作成されているものではありません。 2 売上高および営業収入 営業利益(損失) 当社株主に帰属する (単位:兆円) (単位:億円) -

Instructions

MY DETAILS My Name: Jong B. Mobile No.: 0917-5877-393 Movie Library Count: 8,600 Titles / Movies Total Capacity : 36 TB Updated as of: December 30, 2014 Email Add.: jongb61yahoo.com Website: www.jongb11.weebly.com Sulit Acct.: www.jongb11.olx.ph Location Add.: Bago Bantay, QC. (Near SM North, LRT Roosevelt/Munoz Station & Congressional Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table Drive Capacity Loadable Space Est. No. of Movies/Titles 320 Gig 298 Gig 35+ Movies 500 Gig 462 Gig 70+ Movies 1 TB 931 Gig 120+ Movies 1.5 TB 1,396 Gig 210+ Movies 2 TB 1,860 Gig 300+ Movies 3 TB 2,740 Gig 410+ Movies 4 TB 3,640 Gig 510+ Movies Note: 1. 1st Come 1st Serve Policy 2. Number of Movies/Titles may vary depends on your selections 3. SD = Standard definition Instructions: 1. Please observe the Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table above 2. Mark your preferred titles with letter "X" only on the first column 3. Please do not make any modification on the list. 3. If you're done with your selections please email to [email protected] together with the confirmaton of your order. 4. Pls. refer to my location map under Contact Us of my website YOUR MOVIE SELECTIONS SUMMARY Categories No. of titles/items Total File Size Selected (In Gig.) Movies (2013 & Older) 0 0 2014 0 0 3D 0 0 Animations 0 0 Cartoon 0 0 TV Series 0 0 Korean Drama 0 0 Documentaries 0 0 Concerts 0 0 Entertainment 0 0 Music Video 0 0 HD Music 0 0 Sports 0 0 Adult 0 0 Tagalog 0 0 Must not be over than OVERALL TOTAL 0 0 the Loadable Space Other details: 1. -

DVD LIST 05-01-14 Xlsx

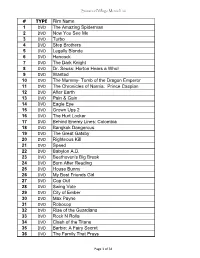

Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 1 DVD The Amazing Spiderman 2 DVD Now You See Me 3 DVD Turbo 4 DVD Step Brothers 5 DVD Legally Blonde 6 DVD Hancock 7 DVD The Dark Knight 8 DVD Dr. Seuss: Horton Hears a Who! 9 DVD Wanted 10 DVD The Mummy- Tomb of the Dragon Emperor 11 DVD The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian 12 DVD After Earth 13 DVD Pain & Gain 14 DVD Eagle Eye 15 DVD Grown Ups 2 16 DVD The Hurt Locker 17 DVD Behind Enemy Lines: Colombia 18 DVD Bangkok Dangerous 19 DVD The Great Gatsby 20 DVD Righteous Kill 21 DVD Speed 22 DVD Babylon A.D. 23 DVD Beethoven's Big Break 24 DVD Burn After Reading 25 DVD House Bunny 26 DVD My Best Friends Girl 27 DVD Cop Out 28 DVD Swing Vote 29 DVD City of Ember 30 DVD Max Payne 31 DVD Robocop 32 DVD Rise of the Guardians 33 DVD Rock N Rolla 34 DVD Clash of the Titans 35 DVD Barbie: A Fairy Secret 36 DVD The Family That Preys Page 1 of 34 Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 37 DVD Open Season 2 38 DVD Lakeview Terrace 39 DVD Fire Proof 40 DVD Space Buddies 41 DVD The Secret Life of Bees 42 DVD Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa 43 DVD Nights in Rodanthe 44 DVD Skyfall 45 DVD Changeling 46 DVD House at the End of the Street 47 DVD Australia 48 DVD Beverly Hills Chihuahua 49 DVD Life of Pi 50 DVD Role Models 51 DVD The Twilight Saga: Twilight 52 DVD Pinocchio 70th Anniversary Edition 53 DVD The Women 54 DVD Quantum of Solace 55 DVD Courageous 56 DVD The Wolfman 57 DVD Hugo 58 DVD Real Steel 59 DVD Change of Plans 60 DVD Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 61 DVD Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters 62 DVD The Cold Light of Day 63 DVD Bride & Prejudice 64 DVD The Dilemma 65 DVD Flight 66 DVD E.T. -

![Download/90/67> [22 May 2015] Hofstee, E](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9857/download-90-67-22-may-2015-hofstee-e-2919857.webp)

Download/90/67> [22 May 2015] Hofstee, E

An analysis of its origin and a look at its prospective future growth as enhanced by Information Technology Management tools. Master in Science (M.Scs.) At Coventry University Management of Information Technology September 2014 - September 2015 Supervised by: Stella-Maris Ortim Course code: ECT078 / M99EKM Student ID: 6045397 Handed in: 16 August 2015 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY Student surname: OLSEN Student first names: ANDERS, HVAL Student ID No: 6045397 Course: ECT078 – M.Scs. Management of Information Technology Supervisor: Stella-Maris Ortim Second marker: Owen Richards Dissertation Title: The Evaluation of eSports: An analysis of its origin and a look at its prospective future growth as enhanced by Information Technology Management tools. Declaration: I certify that this dissertation is my own work. I have read the University regulations concerning plagiarism. Anders Hval Olsen 15/08/2015 i ABSTRACT As the last years have shown a massive growth within the field of electronic sports (eSports), several questions emerge, such as how much is it growing, and will it continue to grow? This research thesis sees this as its statement of problem, and further aims to define and measure the main factors that caused the growth of eSports. To further enhance the growth, the benefits and disbenefits of implementing Information Technology Management tools is appraised, which additionally gives an understanding of the future of eSports. To accomplish this, the thesis research the existing literature within the project domain, where the literature is evaluated and analysed in terms of the key research questions, and further summarised in a renewed project scope. As for methodology, a pragmatism philosophy with an induction approach is further used to understand the field, and work as the outer layer of the methodology. -

Maryland Spring Turkey Hunter Survey – Results Summary August 2017

Maryland Spring Turkey Hunter Survey – Results Summary August 2017 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY This survey was conducted to investigate the preferences and opinions of Maryland’s spring turkey hunters regarding turkey management, populations and regulations. It also was designed to obtain information about hunter characteristics and spring turkey hunting techniques that will allow the Maryland Department of Natural Resources to better manage the turkey resource. A similar survey was conducted in 2007. Surveys were sent to 1,030 hunters who indicated that they hunted turkeys during the spring season on one of the three most recent annual hunter mail surveys. The hunter mail survey randomly surveys approximately seven percent of license-buyers annually to estimate the effort for and harvest of a variety of game species, including turkey. A total of 604 completed spring turkey hunter survey forms were returned. Accounting for non-deliverable surveys, the response rate for the spring turkey hunter survey was 60 percent. Because previous mail survey respondents may have been more likely to respond to this survey, our sample cannot be considered truly random. Nevertheless we feel the hunters that responded were adequately representative of spring turkey hunters in Maryland. About 10,000 resident and non-resident hunters usually pursue spring turkeys annually in Maryland. Therefore our sample represents about six percent of Maryland’s spring turkey hunters. RESULTS Below is a brief summary of the survey responses. Appendix 1 shows the actual survey questions and distribution of all responses. Appendix 2 lists all additional written comments received. Spring Turkey Hunter Characteristics, Attitudes, and Behaviors The average Maryland spring turkey hunter has hunted turkeys in the spring for 16 years and hunted seven days during the 2017 season. -

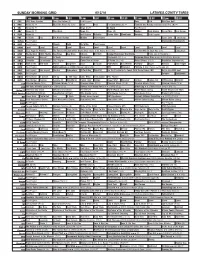

Sunday Morning Grid 6/12/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/12/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid F1 Countdown (N) Å Formula One Racing Canadian Grand Prix. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Underworld: Evolution (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Easy Yoga for Arthritis The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. (TVG) Eat Dirt With Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) Carpenters 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Louder Than Love: The Grande Pavlo Live in Kastoria Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Flashpoint Å Flashpoint (TV14) Å Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Baby Geniuses › (1999) Kathleen Turner. -

Starlog Magazine

WATCHMEN WITCH Silk MOUNTAIN Spectre & INKHEART«ELEVENTH Dwayne (The 16 pages WONDER W Rock) Johnson of action! STARLOG Movie Magic presents battles THE SCIENCE Fl HI. , n if Hi put on y 9\*sses tor lift] •KX3 MP* • Hi Clap for Coraline alongside the Other Father, director Henry Selick (page 28) and star Dakota Fanning (page 24). STARLOG 64 BUNNY TOSSING & OTHER EVENTS Open Season 2 promises more toonish antics 16 SINS OF THE SON Joshua Jackson knows not what he has done 69 IN BRENDAN FRASER'S VIEW It almost always involves greenscreen 20 THE PUSH TO DIRECT Paul McGuigan deals with psychic youth 75 LIFE IN THE ELEVENTH HOUR Rufus Sewell looks to science for answers 24 DAKOTA FANNING SPEAKS... And she has two genre films to talk about! 78 STRANGE ADVENTURES IN TIME & COMICS -6 Murphy Anderson drew them & Buck Rogers | 28 CRAFTING CORALINE s Henry Selick fashions a film the novel » from WATCHMEN TALES #2 |N * | 32 NEW MAN ON WITCH MOUNTAIN 36 A SILKEN LEGACY = Johnson returns for fantasy action Carla Cugino explains her heroic past & present Dwayne y 51 MONSTERS VS. ALIENS! 39 KISS OF THE SILK SPECTRE I Can Earth's unwanted save us from 3-D doom? Malin Akerman just loves the family business §o 56 THE ANIMATED AMAZON 42 LOOK ON MY WORKS, YE MIGHTY... I Wonder Woman battles on in a new DVD war Designer Alex McDowell envisions the world I o O 60 HULK'S ALL-STAR, DOUBLE BRAWL 46 THE ABYSS GAZES ALSO % He fights Wolverine & the Mighty Thor, too Director Zack Snyder makes it all a reality £ ON THE WEEKENDS, THOR WASHES HIS THUNDERWEAR- 4 SMm/April 2009 — President BOOK OF NOTE THOMAS DeFEO We have to recommend The Spirit: The Movie Visual Companion by STARLOG Executive Art Director pal Mark Cotta Vaz (Titan, he, $30). -

DVD E Ang Angelina Ballerina the Silver Locket. DVD E Ang Angelina Ballerina Dance of Friendship

DVD E Ang Angelina Ballerina The Silver locket. DVD E Ang Angelina Ballerina Dance of friendship. DVD E Ang Angelina Ballerina. Dancing on ice DVD E Ang Angelina Ballerina. Sweet valentine DVD E Are Are you a horse? DVD E Bab Baby Mozart DVD E Bar Barkus, Sly and the golden egg DVD E Bat Bats at the library DVD E Beb Bebé : Bebé goes shopping ; Bebé goes to the beach DVD E Ber The Berenstain bears. Christmas tree DVD E Big Big Brown Bear stories DVD E Blu Blue's clues. Get to know Joe! DVD E Bob Bob the Builder When Bob became a builder. DVD E Bob Bob the Builder Digging for treasure DVD E Bob Bob the builder. Truck teamwork DVD E Bob Bob the builder Scoop's favorite adventures DVD E Bob Bob the builder. Building from Scratch DVD E Bus Busytown mysteries. You and me...solve a mystery DVD E Bus Busytown mysteries. The spooky secrets of Busy town DVD E Bus Busytown mysteries. The biggest mysteries ever! DVD E Cai Caillou's holiday movie DVD E Cai Caillou. Caillou the courageous DVD E Cai Caillou Caillou pretends to be ... DVD E Cai Caillou at play DVD E Chi Chicka Chicka 1-2-3 and more stories about counting DVD E Chu Chuggington. The big freeze DVD E Chr Chrysanthemum and more Kevin Henkes stories DVD E Cli Clifford the big red dog. Doggie detectives DVD E Cor Corduroy -- and more stories about caring DVD E Cou Counting crocodiles &, Monster math. DVD E Cri Critter sitter ; & Lulu's magic wand. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/5/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/5/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC 2016 French Open Tennis Men’s Final. From Roland Garros Stadium in Paris. (6) (N) Å Gymnastics P&G Men’s Championships. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week X Games BMX Dirt/Skateboard Women’s Park/Skateboard Park Finals. From Austin, Texas. IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy Winning 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Quilts Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) Eat Dirt With Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) The Allergy Solution, With Leo Galland, MD (TVG) 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder The Show (TVG) Å Smokey Robinson 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Die Another Day ›› (2002, Action) Pierce Brosnan, Halle Berry. (PG-13) The World Is Not Enough 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Paid In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program The Water Horse ››› (2007) Emily Watson.