1926, Vol. 2 in 1896, American Composer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Federal Music Project: an American Voice in Depression-Era Music

Musical Offerings Volume 9 Number 2 Fall 2018 Article 1 10-3-2018 The Federal Music Project: An American Voice in Depression-Era Music Audrey S. Rutt Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Composition Commons, Economic Policy Commons, Education Policy Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Theory Commons, and the Social Welfare Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Rutt, Audrey S. (2018) "The Federal Music Project: An American Voice in Depression-Era Music," Musical Offerings: Vol. 9 : No. 2 , Article 1. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2018.9.2.1 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol9/iss2/1 The Federal Music Project: An American Voice in Depression-Era Music Document Type Article Abstract After World War I, America was musically transformed from an outsider in the European classical tradition into a country of musical vibrance and maturity. These great advances, however, were deeply threatened by the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the consequent Great Depression. -

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus the Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, Conducting

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus The Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, conducting ALAN HOVHANESS is one of those composers whose music seems to prove the inexhaustability of the ancient modes and of the seven tones of the diatonic scale. He has made for himself one of the most individual styles to be found in the work of any American composer, recognizable immediately for its exotic flavor, its masterly simplicity, and its constant air of discovering unexpected treasures at each turn of the road. Meditation on Orpheus, scored for full symphony orchestra, is typical of Hovhaness’ work in the delicate construction of its sonorities. A single, pianissimo tam-tam note, a tone from a solo horn, an evanescent pizzicato murmur from the violins (senza misura)—these ethereal elements tinge the sound of the middle and lower strings at the work’s beginning and evoke an ambience of mysterious dignity and sensuousness which continues and grows throughout the Meditation. At intervals, a strange rushing sound grows to a crescendo and subsides, interrupting the flow of smooth melody for a moment, and then allowing it to resume, generally with a subtle change of scene. The senza misura pizzicato which is heard at the opening would seem to be the germ from which this unusual passage has grown, for the “rushing” sound—dynamically intensified at each appearance—is produced by the combination of fast, metrically unmeasured figurations, usually played by the strings. The composer indicates not that these passages are to be played in 2/4, 3/4, etc. but that they are to last “about 20 seconds, ad lib.” The notes are to be “rapid but not together.” They produce a fascinating effect, and somehow give the impression that other worldly significances are hidden in the juxtaposition of flow and mystical interruption. -

559862 Itunes Copland

AmericAn clAssics cOPlAnD Billy the Kid (complete Ballet) Grohg (One-Act Ballet) Detroit symphony Orchestra leonard slatkin Aaron Copland (1900 –1990) not touch them.” They described Grohg as having large, 5. Grohg Imagines the Dead Are Mocking Him Grohg • Billy the Kid piercing eyes and a hooked nose, who was “… tragic and Grohg begins to hallucinate and imagines that corpses pitiable in his ugliness.” For what is essentially a student are making fun of him and violently striking him. Grohg (1925) for the big time: a one-act, 35-minute ballet for full work, Copland’s score is quite amazing, and on hearing Nevertheless, he joins in their dances. Chaos ensues, pit orchestra plus piano. There was a taste for the parts of it which were rearranged into the Dance then Grohg raises the street-walker over his head and As much as anyone, Copland, who was born in 1900 in bizarre at the time, and if Grohg sounds morbid Symphony of 1929, Stravinsky called it “a very precocious throws her into the crowd. Brooklyn, and died in 1990 in Tarrytown (now Sleepy and excessive, the music was meant to be opus” for a young man then in his early 20s. There are 6. Illumination and Disappearance of Grohg Hollow), New York, established American concert music fantastic rather than ghastly. Also, the need for many influences on the ballet, among them Mussorgsky, The stage turns dark except for a light focused on Grohg’s through his works and his tireless efforts on its behalf. He gruesome effects gave me an excuse for ‘modern’ Satie, Ravel, Stravinsky, and Schmitt, along with jazz and head, and he slowly disappears to music which echoes and his contemporaries not only raised this music to a very rhythms and dissonances. -

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 the Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 The Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr. Richard Benjamin THE GRAMMY® FOUNDATION eonard Bernstein is cele brated as an artist, a CENTER FOP LEAR ll I IJ G teacher, and a scholar. His Lbook Findings expresses the joy he found in lifelong learning, and expounds his belief that the use of the arts in all aspects of education would instill that same joy in others. The Young People's Concerts were but one example of his teaching and scholarship. One of those concerts was devoted to celebrating teachers and the teaching profession. He said: "Teaching is probably the noblest profession in the world - the most unselfish, difficult, and hon orable profession. But it is also the most unappreciated, underrat Los Angeles. Devoted to improv There was an entrepreneurial ed, underpaid, and under-praised ing schools through the use of dimension from the start, with profession in the world." the arts, and driven by teacher each school using a few core leadership, the Center seeks to principles and local teachers Just before his death, Bernstein build the capacity in teachers and designing and customizing their established the Leonard Bernstein students to be a combination of local applications. That spirit Center for Learning Through the artist, teacher, and scholar. remains today. School teams went Arts, then in Nashville Tennessee. The early days in Nashville, their own way, collaborating That Center, and its incarnations were, from an educator's point of internally as well as with their along the way, has led to what is view, a splendid blend of rigorous own communities, to create better now a major educational reform research and talented expertise, schools using the "best practices" model, located within the with a solid reliance on teacher from within and from elsewhere. -

Eastman Notes July 2006

Attention has been paid! Playing inside Eastman Opera Theatre & outside takes aim at Assassins New books by two faculty members Eastman 90 Nine decades of Eastman milestones Winter 2012 FOr ALUMni, PArentS, AnD FrienDS OF tHe eAStMAn SCHOOL OF MUSiC FROM THE DEAN A splendid urgency Every now and then I have the good fortune of hearing a concert that is so riveting, I am reminded why I got into music in the first place. The Eastman Philharmonia’s recent performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, under the guest baton of Brad Lubman, was just such an occasion. Prepared and conducted su- perbly by Brad, and exuberantly performed by students clearly amped up by the music and the occasion, the raw beauty of one of Stravinsky’s greatest works came to stunning life. The power of this experience had nothing to do with outcomes, technologi- cal expertise, assessment, metrics of excellence, or gainful employment upon graduation. This was pure energy funneled into an art form. It was exotically NOTES irrational. It was about the rigorous pursuit of beauty, Volume 30, number 1 pure and simple. Winter 2012 As the national “music movement” grapples with the perception that it has lost precious ground in the fight Editor to keep music in our schools, I was reminded of our na- David raymond tional obsession with practical outcomes, and the chal- Contributing writers lenge of making a case for subjective artistic value in the John Beck Steven Daigle face of such an objectivity-based national agenda. Matthew evans Although we tend to focus on the virtues of music it- Douglas Lowry self, what we are really talking about is the act of learning robert Morris music. -

FREDERICK FENNELL and the EASTMAN WIND ENSEMBLE: the Transformation of American Wind Music Through Instrumentation and Repertoire

FREDERICK FENNELL AND THE EASTMAN WIND ENSEMBLE: The Transformation of American Wind Music Through Instrumentation and Repertoire Jacob Edward Caines Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Master of Arts degree in Musicology School Of Music Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Jacob Edward Caines, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 i Abstract The Eastman Wind Ensemble is known as the pioneer ensemble of modern wind music in North America and abroad. Its founder and conductor, Frederick Fennell, was instrumental in facilitating the creation and performance of a large number of new works written for the specific instrumentation of the wind ensemble. Created in 1952, the EWE developed a new one-to-a-part instrumentation that could be varied based on the wishes of the composer. This change in instrumentation allowed for many more compositional choices when composing. The instrumentation was a dramatic shift from the densely populated ensembles that were standard in North America by 1952. The information on the EWE and Fennell is available at the Eastman School of Music’s Ruth Watanabe Archive. By comparing the repertory and instrumentation of the Eastman ensembles with other contemporary ensembles, Fennell’s revolutionary ideas are shown to be unique in the wind music community. Key Words - EWE (Eastman Wind Ensemble) - ESB (Eastman Symphony Band) - Vernacular - Cultivated - Wind Band - Wind Ensemble - Frederick Fennell - Repertoire i Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the support of many people. Firstly, my advisor, Prof. Christopher Moore. Without his constant guidance, and patience, this document would have been impossible to complete. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives

under the auspices of A GIFT FROM MICHAELS NEW HAVEN • HARTFORD • BRIDGEPORT MERIDEN • WATERBURY • BRISTOL MILFORD • NEW BRITAIN • MANCHESTER MIDDLETOWN • TORRINGTON PROVIDENCE • PAWTUCKET THE KNOWN NAME, THE KNOWN QUALITY SINCE 1900 Concert Calendar WOOLSEY HALL CONCERT SERIES Auspices School of Music - Yale University SEASON 1961-1962 Tuesday, October 10, 1961 GEORGE LONDON, Baritone EXHIBITION Tuesday, November 14, 1961 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA OF Charles Munch, Conductor PAINTINGS Wednesday, December 6, 1961 By JOHN DAY RUDOLF SERKIN Pianist November 10th through November 30th Tuesday, January 9, 1962 ZINO FRANCESCATTI Violinist MUNSON GALLERY EST. 1860 Tuesday, February 6, 1962 275 Orange Street New Haven CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA Free parking for customers George Szell, Conductor Grant Johannesen, Piano Soloist Tuesday, February 20, 1962 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Charles Munch, Conductor WHEN Tuesday, March 13, 1962 DIVIDENDS LUBOSHUTZ AND NEMENOFF Duo-pianists are important You may wish TICKET OFFICE IN THE LOOMIS TEMPLE of MUSIC to consult 101 ORANGE STREET INCOME FUNDS, INC. Investments For Income 152 Temple St. UNiversity 5-0865 New Haven Page Three PROGRAM NOTES Historical and descriptive notes by 3584 WHITNEY AVE. JOHN N. BURK Mount Carmel COPYRIGHT BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. 771telvitqaClwick4 Opp. Sleeping Giant Tel. CHestnut 8-2767 COHHTRY" ELEGY TO THE MEMORY OF MY CLOTHES FRIEND, SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Op. 44 Our Clothes are Country and Casual Classic and in Good Taste By HOWARD HANSON For ten years we have proved this Born in Wahoo, Nebraska, October 28, 1896 Howard Hanson composed this Elegy for the 75th L anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and it was performed by this Orchestra January 20-21, 1956. -

Patriotism, Nationalism, and Heritage in the Orchestral Music of Howard Hanson Matthew Robert Bishop

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Patriotism, Nationalism, and Heritage in the Orchestral Music of Howard Hanson Matthew Robert Bishop Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC PATRIOTISM, NATIONALISM, AND HERITAGE IN THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC OF HOWARD HANSON By MATTHEW ROBERT BISHOP A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2013 Matthew Bishop defended this thesis on March 29, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Broyles Professor Directing Thesis Michael Buchler Committee Member Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university accordance. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply grateful to the superbly talented, knowledgeable, and supportive members of my committee. I am indebted to my thesis advisor, Dr. Michael Broyles, for his expertise in American music and his patient guidance. I also greatly appreciate the encouragement and wisdom of Dr. Douglass Seaton and Dr. Michael Buchler. The research behind this project was made possible by a Curtis Mayes Research Fellowship through the musicology program at The Florida State University. I am truly honored to work and learn among such impressive colleagues, in musicology and beyond. I am continually challenged by them to meet an impossibly high standard, and I am in awe of their impressive intellect, abundant support, and unending devotion to the cause of researching, performing, teaching, and celebrating the art of music. -

ARSC Journal, Vol

NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO ARTS AND PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS By Frederica Kushner Definition and Scope For those who may be more familiar with commercial than with non-commercial radio and television, it may help to know that National Public Radio (NPR) is a non commercial radio network funded in major part through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and through its member stations. NPR is not the direct recipient of government funds. Its staff are not government employees. NPR produces programming of its own and also uses programming supplied by member stations; by other non commercial networks outside the U.S., such as the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC); by independent producers, and occasionally by commercial networks. The NPR offices and studios are located on M Street in Washington, D.C. Programming is distributed via satellite. The radio programs included in the following listing are "arts and performance." These programs were produced or distributed by the Arts Programming Department of NPR. The majority of the other programming produced by NPR comes from the News and Information Department. The names of the departments may change from time to time, but there always has been a dichotomy between news and arts programs. This introduction is not the proper place for a detailed history of National Public Radio, thus further explanation of the structure of the network can be dispensed with here. What does interest us are the varied types of programming under the arts and performance umbrella. They include jazz festivals recorded live, orchestra concerts from Europe as well as the U.S., drama of all sorts, folk music concerts, bluegrass, chamber music, radio game shows, interviews with authors and composers, choral music, programs illustrating the history of jazz, of popular music, of gospel music, and much, much more. -

Sunday, December 23, 2012

Friday, December 7, 2012 – Sunday, December 23, 2012 Friday, December 7, 2012 6:00 PM Ciminelli Lounge Secondary Piano Recital. 7:00 PM Hatch Recital Hall Student Degree Recital – Siddharth Dubey, voice. Candidate for the Bachelor of Music degree from the studio of Robert Swensen. 8:00 PM Kodak Hall Eastman-Rochester Chorus and Eastman School Symphony Orchestra William Weinert and Yunn-Shan Ma, conductors. Music of Walton, Elgar, and Williams. Saturday, December 8, 2012 11:30 AM Howard Hanson Hall Piano Departmental Recital – Featuring the students of Vincent Lenti and Tony Caramia. 12:00 PM Ciminelli Lounge Secondary Piano recital. 2:00 PM Ciminelli Lounge Chamber Music 281/481 Recital. 3:00 PM Howard Hanson Hall ECMS Recital. 3:30 PM Hatch Recital Hall Student Degree Recital – Jessica Wilkins, oboe. Candidate for the Bachelor of Music degree from the studio of Richard Killmer. 6:00 PM Howard Hanson Hall ECMS Studio Recital – Trumpet students of Natalie Fuller. 6:00 PM Ciminelli Lounge Chamber Music 281/481 Recital. 7:00 PM Hatch Recital Hall Student Degree Recital – Kelsey Hayes, voice. Candidate for the Bachelor of Music degree from the studio of Jan Opalach. 7:30 PM Kodak Hall Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra – Messiah. Eric Townell, guest conductor. Rochester Oratorio Society. Sarah Hibbard, soprano; Stephanie Lauricella, mezzo-soprano; Jeffrey Halili, tenor; Lawrence Craig, bass. Tickets $22 - $65. 9:00 PM Hatch Recital Hall Student Degree Recital – Cahill Smith, piano. Candidate for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree from the studio of Natalya Antonova. Sunday, December 9, 2012 1:00 PM Memorial Art Gallery Going for Baroque – Eastman graduate student Karl Robson will give a 25-minute presentation and and mini-recital on the Italian Baroque organ. -

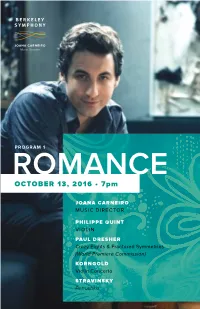

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services.