Australian Science Fiction Review 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7322/the-nemedian-chroniclers-22-ws16-27322.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]

REHeapa Winter Solstice 2016 By Lee A. Breakiron A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON Few fiction authors are as a widely published internationally as Robert E. Howard (e.g., in Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Yugoslavian). As former REHupan Vern Clark states: Robert E. Howard has long been one of America’s stalwarts of Fantasy Fiction overseas, with extensive translations of his fiction & poetry, and an ever mushrooming distribution via foreign graphic story markets dating back to the original REH paperback boom of the late 1960’s. This steadily increasing presence has followed the growing stylistic and market influence of American fantasy abroad dating from the initial translations of H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham House collections in Spain, France, and Germany. The growth of the HPL cult abroad has boded well for other American exports of the Weird Tales school, and with the exception of the Lovecraft Mythos, the fantasy fiction of REH has proved the most popular, becoming an international literary phenomenon with translations and critical publications in Spain, Germany, France, Greece, Poland, Japan, and elsewhere. [1] All this shows how appealing REH’s exciting fantasy is across cultures, despite inevitable losses in stylistic impact through translations. Even so, there is sometimes enough enthusiasm among readers to generate fandom activities and publications. We have already covered those in France. [2] Now let’s take a look at some other countries. GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND SWITZERLAND The first Howard stories published in German were in the fanzines Pioneer #25 and Lands of Wonder ‒ Pioneer #26 (Austratopia, Vienna) in 1968 and Pioneer of Wonder #28 (Follow, Passau, Germany) in 1969. -

Fanscient 17

FIRST ISSUE SEPTEMBER _____ 1947 FAHSCIEHT ^?RTLAND __ The FANSCIFNT In each issue, your editor will sound off here on whatever occurs to him. Tho at the front of the booK, it’s actually the last thins written. First of all,I’d like to take this opportunity to thunk A. E. van Vogt for bus wholehearted co-opera tion in providing the material which appears here. Thanks also to all who gave material, cash and time, As I write, it’s all stencilled, The Fhilcm Mem ory Book Edition is done and when 5 more pages are mimeoed we’ll be thru(except for stapling, folding, wrapping and addressing)(How did I get into rhis?) To make the Philcon Book, we had to get this out a good month before we intended. As a result, we hud to do 4 months work in 1. 'Corking in this for mat was all new to us and all the details had to be thrashed cut. On the whole, we're pretty well sat isfied dvr a first issue. VA hope you are too. On locking over this is"ue,I find we haven’t said much about The PORTLAND SClENCE-FANTASY SOCIETY. Our News Bulletin is mostly about the club, but I guess we’re entitled to a bit cf a brag about the newest' but ere of the most active major fan clubs the country. We haven’t got authors or prominent fen but there’s plenty you’ll get to know. Ralph Rayburn Phillips' work in several fanzines has al ready made ham well known (see Back Cover). -

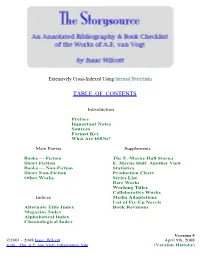

Table of Contents

Extensively Cross-Indexed Using Internal Hyperlinks TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Preface Important Notes Sources Format Key What Are ISBNs? Main Entries Supplements Books — Fiction The E. Mayne Hull Stories Short Fiction E. Mayne Hull: Another View Books — Non-Fiction Statistics Short Non-Fiction Production Chart Other Works Series List Rare Works Working Titles Collaborative Works Indices Media Adaptations List of Fix-Up Novels Alternate Title Index Book Revisions Magazine Index Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Version 5 ©2001 - 2008 Isaac Wilcott April 9th, 2008 Icshi: The A.E. van Vogt Information Site (Version History) Preface This new document, the Storysource, replaces both the Database and Compendium by combining the two. (I suppose you could call this a "fix-up" bibliography since it is the melding of previously "published" material into a new unified whole. And, in the true van Vogtian tradition, I've not only revised it but I've given it a new title as well.) The last versions of both are still available for download as a single ZIP file for those who would like them for whatever reason. The format of the Compendium has been retained with only a few alterations while adding the bibliographic information of the Database. A section for short stories has accordingly been added. The ugly and outdated Database is eliminated, while retaining all of its positive traits, and the usefulness of the Compendium is drastically improved. No longer will you have to jump between the two while looking something up — all information has been pooled into just one document. This new format's interface is more intuitive, alphabetically arranged rather than chronological, and with all items thoroughly cross- indexed with internal hyperlinks. -

Forte JA T 2010.Pdf (404.2Kb)

“We Werenʼt Kidding” • Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 By Joseph A. Forte Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Robert P. Stephens (chair) Marian B. Mollin Amy Nelson Matthew H. Wisnioski May 03, 2010 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Astounding Science-Fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr., sci-fi, science fiction, pulp magazines, culture, ideology, Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, American exceptionalism, capitalism, 1939 Worldʼs Fair, Cold War © 2010 Joseph A. Forte “We Werenʼt Kidding” Prediction as Ideology in American Pulp Science Fiction, 1938-1949 Joseph A. Forte ABSTRACT In 1971, Isaac Asimov observed in humanity, “a science-important society.” For this he credited the man who had been his editor in the 1940s during the period known as the “golden age” of American science fiction, John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell was editor of Astounding Science-Fiction, the magazine that launched both Asimovʼs career and the golden age, from 1938 until his death in 1971. Campbell and his authors set the foundation for the modern sci-fi, cementing genre distinction by the application of plausible technological speculation. Campbell assumed the “science-important society” that Asimov found thirty years later, attributing sci-fi ascendance during the golden age a particular compatibility with that cultural context. On another level, sci-fiʼs compatibility with “science-important” tendencies during the first half of the twentieth-century betrayed a deeper agreement with the social structures that fueled those tendencies and reflected an explication of modernity on capitalist terms. -

By Lee A. Breakiron a CIMMERIAN WORTHY of the NAME, PART

REHEAPA Vernal Equinox 2014 By Lee A. Breakiron A CIMMERIAN WORTHY OF THE NAME, PART THREE During his crusade to revitalize Robert E. Howard fanzines with his The Cimmerian, Leo Grin not only initiated a blog, as we saw last time, but also started publishing a new chapbook series called The Cimmerian Library. They were in the same format as the TC journal issues, but had reddish copper covers in a run of 100 copies for $15.00 each. He issued four titles (“volumes”): REHupan Rob Roehm’s An Index to Cromlech and The Dark Man (2005), REHupan Chris Gruber’s “Them’s Fightin’ Words”: Robert E. Howard on Boxing (2006) citing all of Howard’s quotations on the manly sport from his correspondence, with an introduction and index; John D. Haefele’s A Bibliography of Books and Articles Written by August W. Derleth Concerning Derleth and the Weird Tale and Arkham House Publishing (2006) with one “Addenda” [sic] (2008); and Don Herron’s “Yours for Faster Hippos”: Thirty Years of “Conan vs. Conantics” (2007) containing his pivotal critique of REH pasticheurs, especially L. Sprague de Camp, as well as some personal commentary on it and on Bran Mak Morn, Karl Edward Wagner, and Bruce Lee. And to properly celebrate the Centennial of Howard’s birth, as well as the 70th anniversary of his death, the 60th year since the publication of the landmark Arkham House volume Skull-Face and Others, and the 20th year since the first pilgrimage of REHupans to Cross Plains, Texas, Grin wondered what he could “do to make it extra special, to truly convey the respect and admiration I have for the man and his writings?” (Vol. -

The Key of the Mysteries

THE KEY OF THE MYSTERIES (LA CLEF DES GRANDS MYSTÈRES) BY ELIPHAS LEVI THE KEY OF THE MYSTERIES ACCORDING TO ENOCH, ABRAHAM, HERMES TRISMEGISTUS AND SOLOMON BY ELIPHAS LEVI TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY ALEISTER CROWLEY “Religion says: ‘Believe and you will un- derstand.’ Science comes to say to you: ‘Un- derstand and you will believe.’ “At that moment the whole of science will change front; the spirit, so long dethroned and forgotten, will take its ancient place; it will be demonstrated that the old traditions are all true, that the whole of paganism is only a system of corrupted and misplaced truths, that it is sufficient to cleanse them, so to say, and to put them back again in their place, to see them shine with all their rays. In a word, all ideas will change, and since on all sides a multitude of the elect cry in concert, ‘Come, Lord, come!’ why should you blame the men who throw themselves forward into that majestic future, and pride themselves on having foreseen it?” (J. De Maistre, Soirées de St. Petersbourg.) TRANSLATOR’S NOTE IN the biographical and critical essay which Mr. Waite prefixes to his Mysteries of Magic he says: ‘A word must be added of the method of this digest, which claims to be something more than translation and has been infinitely more laborious. I believe it to be in all respects faithful, and where it has been necessary or possible for it to be literal, there also it is invariably literal.’ We agree that it is either more or less than translation, and the following examples selected at haz- ard in the course of half-an-hour will enable the reader to judge whether Mr. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Aunt Jane's Nieces out West by Edith Van Dyne

Aunt Jane's Nieces Out West By Edith Van Dyne CONTENTS CHAPTER I - CAUGHT BY THE CAMERA CHAPTER II - AN OBJECT LESSON CHAPTER III - AN ATTRACTIVE GIRL CHAPTER IV - AUNT JANE'S NIECES CHAPTER V - A THRILLING RESCUE CHAPTER VI - A. JONES CHAPTER VII - THE INVALID CHAPTER VIII - THE MAGIC OF A NAME CHAPTER IX - DOCTOR PATSY CHAPTER X - STILL A MYSTERY CHAPTER XI - A DAMSEL IN DISTRESS CHAPTER XII - PICTURES, GIRLS AND NONSENSE CHAPTER XIII - A FOOLISH BOY CHAPTER XIV - ISIDORE LE DRIEUX CHAPTER XV - A FEW PEARLS CHAPTER XVI - TROUBLE CHAPTER XVII - UNCLE JOHN IS PUZZLED CHAPTER XVIII - DOUBTS AND DIFFICULTIES CHAPTER XIX - MAUD MAKES A MEMORANDUM CHAPTER XX - A GIRLISH NOTION CHAPTER XXI - THE YACHT "ARABELLA" CHAPTER XXII - MASCULINE AND FEMININE CHAPTER XXIII - THE ADVANTAGE OF A DAY CHAPTER XXIV - PICTURE NUMBER NINETEEN CHAPTER XXV - JUDGMENT CHAPTER XXVI - SUNSHINE AFTER RAIN CHAPTER I - CAUGHT BY THE CAMERA "This is getting to be an amazing old world," said a young girl, still in her "teens," as she musingly leaned her chin on her hand. "It has always been an amazing old world, Beth," said another girl who was sitting on the porch railing and swinging her feet in the air. "True, Patsy," was the reply; "but the people are doing such peculiar things nowadays." "Yes, yes!" exclaimed a little man who occupied a reclining chair within hearing distance; "that is the way with you young folks—always confounding the world with its people." "Don't the people make the world, Uncle John?" asked Patricia Doyle, looking at him quizzically. -

Back Numbers 11 Part 1

In This Issue: Columns: Revealed At Last........................................................................... 2-3 Pulp Sources.....................................................................................3 Mailing Comments....................................................................29-31 Recently Read/Recently Acquired............................................32-39 The Men Who Made The Argosy ROCURED Samuel Cahan ................................................................................17 Charles M. Warren..........................................................................17 Hugh Pentecost..............................................................................17 P Robert Carse..................................................................................17 Gordon MacCreagh........................................................................17 Richard Wormser ...........................................................................17 Donald Barr Chidsey......................................................................17 95404 CA, Santa Rosa, Chandler Whipple ..........................................................................17 Louis C. Goldsmith.........................................................................18 1130 Fourth Street, #116 1130 Fourth Street, ASILY Allan R. Bosworth..........................................................................18 M. R. Montgomery........................................................................18 John Myers Myers ..........................................................................18 -

The Operas of Paul Stuart Based on Libretti by Sally M. Gall Sandra Gayle Boysen

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 The Operas of Paul Stuart Based on Libretti by Sally M. Gall Sandra Gayle Boysen Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE OPERAS OF PAUL STUART BASED ON LIBRETTI BY SALLY M. GALL By Sandra Gayle Boysen A Trea ise submi ed to the School of Music in par ial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doc or of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semes er, 2003 The members of the Commi ee approve the rea ise of Sandra Gayle Boysen defended on November 7, 2003. ___________________________________ Roy Delp Professor Direc ing Trea ise ___________________________________ Timothy Hoekman Outside Commi ee Member ___________________________________ Larry Gerber Commi ee Member ___________________________________ 5anice Harsanyi Commi ee Member The Office of Gradua e S udies has verified and approved the above named commi ee members. ii AC6NO7LEDGMENTS To Paul S uar , his wife Karin and their daughter, Vanessa, go my gra i ude for heir willingness to share their time and their home for the many interviews held there during research for this trea ise. To Paul, I give special thanks for his generosi y in providing invaluable resources such as his primary research notebooks, his ini ial composi ional ske ches, and his thorough documenta ion of correspondence and other ma erials rela ed to the crea ion of these operas. My thanks go to Dr. Sally M. Gall for answering my many ques ions so pa iently hrough many e8mail e9changes. -

Southwestern Montana Music Assessment : a Comparison Between Rural Montana and the Extreme Rural National Assessment of Educatio

Southwestern Montana Music Assessment : a comparison between rural Montana and the extreme rural national assessment of educational progress sample by Richard T Sietsema A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Education Montana State University © Copyright by Richard T Sietsema (1988) Abstract: The purpose of this study was to assess the music background and music achievement of 13-year-old rural students in Southwestern Montana. Data for the rural Montana students were established through utilization of selected music exercises found in the Second National Music Assessment component of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Responses to the assessment exercises of the Southwestern Montana students, expressed as percentages, were compared with responses of 13-year-old student's in the population sample drawn from the "Extreme Rural" type of community in the "Western Region" of the United States. The population for the author's study consisted of all 13-year-olds attending designated elementary schools in a six county area in Southwestern Montana. One, two, and three teacher K-8 schools were referred to as "Rural" while larger K-8 schools were referred to as "Town Schools." Music in the "Rural" schools was taught primarily by the classroom teacher while certified music specialists taught music in the "Town" schools. The NAEP music assessment was designed to gather data concerning demographics, home environment, in-school and outside of school activities, as well as cognitive and affective responses to selected music exercises. The Montana assessment booklet was developed by the author utilizing released exercises from the 1978-79 NAEP Music Assessment and was administered during the Fall of 1986. -

THE RISE of the NEW HYBORIAN LEGION, PART FIVE by Lee A

REHeapa Summer Solstice 2019 THE RISE OF THE NEW HYBORIAN LEGION, PART FIVE By Lee A. Breakiron As we saw in our first installment [1], the Robert E. Howard United Press Association (REHupa) was founded in 1972 by a teen-aged Tim Marion as the first amateur press association (apa) devoted to Howard. Reforms by the next Official Editor (OE), Jonathan Bacon, had gone a good way toward making the fanzine Mailings look less amateurish, which in turn attracted more and better members. There was still too many Mailing Comments (MCs) being made relative to the material worth commenting on, still too little that concerned Howard himself, and still too much being said about tangential matters (pastiches, comics, gaming, etc.) or personal affairs. A lot of fan fiction and poetry was being contributed, but this did garner a lot of appreciation and commentary from the other members. The next OE, Brian Earl Brian, put in a lot of work guiding the organization, though not always competently. Former, longtime REHupan James Van Hise wrote the first comprehensive history of REHupa through Mailing #175. [2] Like him, but more so, we are focusing only on noteworthy content, especially that relevant to Howard. Here are the highlights of Mailings #46 through #55. In Mailing #46 (July, 1980), Brown features some information on electrostencilling and a trip report on the Columbus, Ohio, science fiction and fantasy convention Marcon. He mentions L. Sprague de Camp’s story “Far Babylon,” in which the lost soul of Robert E. Howard appears, portrayed in a positive light. On a matter of current contention, he declares that anyone should be able to “frank” (reproduce in their zine) any material or statements by other people and that no one should have any expectation of privacy from those outside the apa.