Att Ddc Carlton Expe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDITED TRANSCRIPT Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call

NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT, Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call REFINITIV STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call EVENT DATE/TIME: NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT REFINITIV STREETEVENTS | www.refinitiv.com | Contact Us ©2020 Refinitiv. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Refinitiv content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Refinitiv. 'Refinitiv' and the Refinitiv logo are registered trademarks of Refinitiv and its affiliated companies. 1 NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT, Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Adam Fogelson: STX Films - Chairman Andy Warren: Eros STX Global Corporation - CFO Bob Simonds: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-Chairman & CEO Drew Borst: Eros STX Global Corporation - EVP Investor Relations & Business Development Noah Fogelson: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-President Rishika Lulla Singh: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-President & Director CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Eric Katz, Wolfe Research, LLC - Research Analyst Robert Routh, FBN Securities, Inc., Research Division - Research Analyst Robert Fishman, MoffettNathanson LLC - Analyst Ted Cronin, Citigroup Inc., Research Division - Research Analyst Tim Nollen, Macquarie Research - Senior Media Analyst PRESENTATION Operator Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to Eros STX Global Corporation Business Update Call. This call is being broadcast live on the Internet, and a replay of the call will be available on the company's website. The company published earlier certain financial information, including a 20-F transition report and 6-K filing which are available on the company's website. The company would like to remind everyone listening that during this call, it will be making forward- looking statements under the safe harbor provisions of the federal securities laws. -

CHANNEL LISTING FIBE TV from Your Smartphone

Now you can watch your Fibe TV Download the Fibe TV content and manage recordings app today at CHANNEL LISTING FIBE TV from your smartphone. bell.ca/fibetvapp. CURRENT AS OF FEBRUARY 25, 2016. E MUCHMUSIC HD ........................................1570 TREEHOUSE ...................................................560 GOOD E! .............................................................................621 MYTV BUFFALO (WNYO) ..........................293 TREEHOUSE HD .........................................1560 E! HD ...................................................................1621 MYTV BUFFALO HD ..................................1293 TSN1 ....................................................................400 F N TSN1 HD ..........................................................1400 A FOX ......................................................................223 NBC - EAST .................................................... 220 TSN RADIO 1050 ..........................................977 ABC - EAST .......................................................221 FOX HD ............................................................1223 NBC HD - EAST ...........................................1220 TSN RADIO 1290 WINNIPEG ..................979 ABC HD - EAST ............................................. 1221 H NTV - ST. JOHN’S .........................................212 TSN RADIO 990 MONTREAL ................980 A&E .......................................................................615 HGTV................................................................ -

Apple Online Promo Code

1 / 2 Apple Online Promo Code TechBargains has great deals, coupons and promo codes for Amazon. ... Amazon has the Apple AirPods Pro for a low $199.99 Free Shipping. ... Amazon is the largest Online Retailer and has become synonymous with shopping online.. Apple AirPods Pro were just announced yesterday, but AppleInsider readers can save $20 instantly on the new earphones with coupon.. Buy wine & spirits online or visit our store in Rochester, NY! ... Download a Apple Barn Winery coupon and find information on Wineries in the Great Smoky .... From the latest iPhone and iPad models to the new MacBook Air with Touch ID and Apple Pay which is perfect for those who enjoy online shopping without regrets .... FREE More Deals & Coupons Like "SwitchResX 4 for Mac downloads for " Feb 25, ... As Couponxoo's tracking, online shoppers can recently get a save of 50% on ... January 1, 2021. com is a website that aggregates Mac and Apple related .... As @Christoph Wimberge notes this is old news. Apple is now supporting this. You cannot officially get promo codes for IAP currently. See here .... Coupons and offers on this page are gathered from around the internet. These deals are subject to availability, and Apple terms, conditions, and exclusions may .... Promo Codes CRM Buy CRM Voucher Code 30 CRM Ontraport Kinja Deals Buy CRM Verified Discount Online Coupon Ontraport CRM Coupon 10 CRM .... Get up to 10% Off your online order with our new Apple coupons for April 2021. Shop with our 16 top-rated Apple promo codes available today at SFGate. For online returns, you'll need your Apple ID. -

Alphabetical Channel Guide 800-355-5668

Miami www.gethotwired.com ALPHABETICAL CHANNEL GUIDE 800-355-5668 Looking for your favorite channel? Our alphabetical channel reference guide makes it easy to find, and you’ll see the packages that include it! Availability of local channels varies by region. Please see your rate sheet for the packages available at your property. Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package 5StarMAX 712 774 Cinemax A&E 95 488 ABC 10 WPLG 10 410 Local Local Local Local ABC Family 62 432 AccuWeather 27 ActionMAX 713 775 Cinemax AMC 84 479 America TeVe WJAN 21 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package American Heroes Channel 112 Animal Planet 61 420 AWE 256 491 AXS TV 493 Azteca America 399 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package Bandamax 625 En Espanol Package Bang U 810 Adult BBC America 51 BBC World 115 Becon WBEC 397 Local Local Local Local beIN Sports 214 502 beIN Sports (en Espanol) 602 En Espanol Package BET 85 499 BET Gospel 114 Big Ten Network 208 458 Bloomberg 222 Boomerang 302 Bravo 77 471 Brazzers TV 811 Adult CanalSur 618 En Espanol Package Cartoon Network 301 433 CBS 4 WFOR 4 404 Local Local Local Local CBS Sports Network 201 459 Centric 106 Chiller 109 CineLatino 630 En Espanol Package Cinemax 710 772 Cinemax Cloo Network 108 CMT 93 CMT Pure Country 94 CNBC 48 473 CNBC World 116 CNN 49 465 CNN en Espanol 617 En Espanol Package CNN International 221 Comedy Central 29 426 Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package -

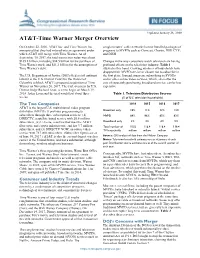

AT&T-Time Warner Merger Overview

Updated January 26, 2018 AT&T-Time Warner Merger Overview On October 22, 2016, AT&T Inc. and Time Warner Inc. conglomerates’ cable networks license bundled packages of announced that they had entered into an agreement under programs to MVPDs such as Comcast, Charter, DIRECTV, which AT&T will merge with Time Warner. As of and DISH. September 30, 2017, the total transaction value was about $105.8 billion, including $84.5 billion for the purchase of Changes in the way consumers watch television are having Time Warner stock, and $21.3 billion for the assumption of profound effects on the television industry. Table 1 Time Warner’s debt. illustrates this trend. Growing numbers of households have dropped their MVPD service or chosen not to subscribe in The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a civil antitrust the first place. Instead, many are subscribing to SVODs lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of and/or other online video services, which, even after the Columbia to block AT&T’s proposed acquisition of Time cost of separately purchasing broadband service, can be less Warner on November 20, 2017. The trial, overseen by U.S. expensive. District Judge Richard Leon, is set to begin on March 19, 2018. Judge Leon said the trial would last about three Table 1. Television Distribution Sources weeks. (% of U.S. television households) The Two Companies 2014 2015 2016 2017 AT&T is the largest U.S. multichannel video program distributor (MVPD). It provides programming to Broadcast only 10% 11% 12% 13% subscribers through three subscription services: (1) MVPD 88% 86% 85% 82% DIRECTV, a satellite-based service with 20.6 million subscribers, (2) U-Verse, a service that uses the AT&T Broadband only 2% 3% 4% 5% fiber optic and copper infrastructure and has 3.7 million Total number of 115.5 116.4 116.4 118.4 subscribers, and (3) DIRECTV NOW, an online video TV households million million million million service with 787,000 subscribers. -

Ftc-2018-0091-D-0015-163436.Pdf

December 28, 2018 The Honorable Joseph Simons Chairman Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20580 Dear Chairman Simons, Thank you for inviting public comment on the question of whether U.S. antitrust agencies should publish new vertical merger guidelines, and how those guidelines should address competitive harms, transaction-related efficiencies, and behavioral remedies. We submit these comments on behalf of the Writers Guild of America West (“WGAW”), a labor organization representing more than 10,000 professional writers of motion pictures, television, radio, and Internet programming, including news and documentaries. Our members and the members of our affiliate, Writers Guild of America East (jointly, “WGA”) create nearly all of the scripted entertainment viewed in theaters and on television today as well as most of the original scripted series now offered by online video distributors (“OVDs”) such as Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Crackle, and more. The Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines (“Guidelines”), originally issued in 1984,1 are the governing document of U.S. vertical antitrust enforcement. They rely, however, upon outdated economic theories that not only fail to promote and protect competition, but, in some cases, obstruct appropriate antitrust enforcement. Large vertical mergers in key industries have caused harm to consumers and failed to deliver on their promised innovations, efficiencies, and public benefits. The current Guidelines’ bias toward false negatives, or non-findings of harm, enables incumbents to consolidate market power and undermine competition. Recent vertical mergers in the telecommunications and entertainment industries illustrate the deficiencies of the current regulatory regime and provide evidence of the need for new guidelines. -

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

368442: the Business of Entertainment > Syllabus | Concourse

368442: The Business of Entertainment MGMT-X 403.31 Summer 2019 Section 1 4 Credits 06/27/2019 to 09/05/2019 Modified 09/15/2019 Meeting Times The class meets Thursdays from 7:00 PM - 10:00 PM beginning Thursday, June 27, 2019 and with the last class on Thursday, September 5, 2019. Location: UCLA, Dodd Hall, Room 161 I will open the modules for each week on Monday morning so you have time to review the topic of the week and look over the articles I recommend to read that cover the topic as well. Description With the entertainment industry converging into a worldwide mass media, both business and operation models continue to rapidly evolve. This introductory course for producers, directors, writers, development personnel, and aspiring media executives examines the changing business issues associated with the entertainment industry. Through lectures, discussions with industry guests, and case studies, instruction focuses on current business and production issues and introduces new business models to navigate content onto new distribution platforms. Some history is highlighted to provide a context for current practices and potential. The course also features opportunities to meet senior entertainment industry executives in various sectors. Topics include financing, contracts, intellectual property issues, licensing, worldwide theatrical marketing and distribution, worldwide home entertainment marketing and distribution, worldwide television production and distribution, multi-channel network distribution and opportunities, the impact of piracy, and leveraging new distribution platforms. By the end of the course, students should have an understanding of the opportunities available in the business of entertainment. Objectives After 40 years of working in the entertainment industry, I am excited to share what I’ve learned. -

Cinedigm Corp. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) ______

Dear Stockholders, Cinedigm put together a remarkable series of accomplishments over the last fiscal year, completing the Company’s business transformation by solidifying our unique position as a key player in the explosively growing OTT/streaming business. Here’s what we accomplished this year: First, we developed several new streaming channels including Comedy Dynamics and The Bob Ross Channel to build our portfolio to 16 premium streaming channels either launched or under contract to launch. We will soon be at 20 channels and plan to get to 30 in the next 18 months. This gives Cinedigm a large, meaningful and growing channel share on the program guide for every key streaming platform and device. Most of these new channels will be set up in a similar fashion to our recent Bob Ross, All 3 Media,, Team Whistle and LiveXLive channel deals, where we partnered with established branded entertainment companies that bring huge amounts of content to the table and then we operate and launch with our major distribution partners like Roku, Amazon, Tubi, and Samsung. We have a robust deal pipeline of these potential premium new partners and channels now because we have clearly established Cinedigm as the “go to” independent streaming company that can employ our state-of-the-art proprietary Matchpoint technology, an enormous streaming distribution platform and device reach, and a huge digital content library to help launch streaming channels across the entire OTT ecosystem. We can do all that quickly, cost effectively and with almost ubiquitous distribution potential on every device and platform. The quality of the business partners reflected in our new channel deals clearly demonstrates that the entertainment industry understands the advantages of doing business with Cinedigm in the exploding streaming space. -

Channel Lineup

D I R E C T V™ Marine Seasonal Package more than tv Galaxy 3C , 95 West Beam Channels DIRECTOTAL - BASIC PACKAGE DIRECTOTAL - Annual Basic Package * English Video Channels US $28.00 (Monthly) * English Video Channels * DIRECTV VARIETY KIDS 201 ON DIRECTV 217 FX 250 HGTV 304 Cartoon Network 207 A & E 219 SYFY 254 Spike USA 308 Nickelodeon LA 208 Sony West 222 E! Entertainment 256 A&E USA 314 Disney 209 AXN 224 Glitz 260 MTV USA 316 Disney XD 213 TNT Series 228 Lifetime 262 VHI USA 321 ZooMoo 215 Comedy Central 229 Discovery Home & Health 264 MTV LA 322 Nickelodeon USA 216 TBS Very Funny 233 Food Network 330 Discovery Kids CIMEMA WORLD SPORTS 502 TNT 702 CNN 736 Discovery Turbo 600 DIRECTV Sports Portal 503 Golden 706 CNN International 740 Discovery Travel & Living 610 DIRECTV Sports 504 Turner Classic Movies 710 Bloomberg 742 History Channel 644 NBA TV INT'L 508 Studio Universal 712 Weather Nation 744 History Channel 2 654 Golf USA 510 Paramount 730 National Geographic 746 Film & Arts 511 AMC 732 Discovery 756 History USA 517 Golden Edge 734 Animal Planet 768 BBC World HD Channels 1201 DIRECTV HD 1510 Paramount HD 1308 Nick HD 1630 Formula 1 HD 1312 Disney HD 1742 History Channel HD 1503 Golden HD Audio Channels 900 Music Mix 918 Classic R&B 940 Reggae 960 Opera 901 Hottest Hits 922 70's Hits 942 Soft Hits 978 88.9 902 Adult Comtemporary 924 80's Hits 944 Love Songs 979 RQ 910 904 Hot Jamz 926 90 Hits 946 Beautiful Instrumentals 980 1090 am 906 Euro Hits 928 Latin Contemporary 948 New Age 982 Caracol 908 Dance 930 Musica de las Americas -

22 Vs. Earth .2021`` DIRECT DOWNLOAD LINK FREE FULL 2160P

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/43ftj MOVIES ``22 Vs. Earth .2021`` DIRECT DOWNLOAD LINK FREE FULL 2160P A few sec ago Don’t miss!~MAXFLIX HD~! Where to Watch 22 vs. Earth (2021) Online Free? [DVD-ENGLISH] 22 vs. Earth (2021) Full Movie, 22 vs. Earth (2021) Full MovieS Free HD Google Drive!! 22 vs. Earth (2021) with English Subtitles ready for download,22 vs. Earth (2021) ::: 720p, 1080p, BrRip, DvdRip, High Quality. See 22 vs. Earth (2021) Full Movie in HD VERSION [⬇⬇⬇⬇⬇⬇⬇⬇⬇⬇⬇] ► 22 vs. Earth (2021) Full movie DIRECT LINK FREE ::: https://www.competize.com/en/league/view/121721-movies-22-vs- earth-direct-download-link Set before the events of ‘Soul’, 22 refuses to go to Earth, enlisting a gang of 5 new souls in attempt of rebellion. However, 22’s subversive plot leads to a surprising revelation about the meaning of life. Registration is fast and easy. You will have the opportunity to Watch when you register to get the complete episode FIND US ► Instagram: https://instagram.com ► Twitter: https://twitter.com ► Facebook: https://www.facebook.com Details of “22 vs. Earth (2021)” Title: 22 vs. Earth (2021) Full movie 22 vs. Earth (2021) ► STREAM OR DOWNLOAD HERE Quality: HD 720p, 1080p, 4K Release: 2021-04-30 Running time: 00:09:00 Genre: Family, Animation, Comedy Stars: Tina Fey, Alice Braga, Richard Ayoade, Micah Chen, Adela Drabek, Aiyanna Miorin, Karee Ducharme, Samantha Ho, Azriel Dalman, Juliana Alcaron Label and Keywords: earth, prequel, planet earth, soul, short film, life 22 vs. Earth (2021) Premiere Kijk Maar 22 vs. Earth (2021) Ser FilmThe 22 vs. -

Television Entertainment a TWO PART CAT SERIES

Television Entertainment A TWO PART CAT SERIES CAT Web site: sirinc2.org/a16cat/ Television Entertainment Twopart presentation series: • Broadcast vs. Internet Television (Streaming) – Sept. 17 • Smart TV’s and Streaming Devices • Streaming Sites • Finding Programs to Watch Television Viewing Options 3 Basic ways to get video content: • Service provider (Xfinity, AT&T, Wave, etc.) • Streaming apps on your Smart TV • Streaming apps via external streaming device Television Service Provider (Xfinity, AT&T, etc.) “Cut-the-Cord” Streaming App Television Smart TV or Ext. Streaming Streaming App Internet Service Device Streaming App Internet Streaming Smart TV’s • Primary purpose of any TV is to display video content • Smart TV’s are “Smart” because they have apps to access a variety of additional media services • Almost all newer TV’s are Smart TV’s (some “smarter” than others) • Newer TV’s are rapidly getting “Smarter” • Depending on the age of your TV and/or needs, you may want to purchase a external streaming device Article Link to: What is a Smart TV? https://www.digitaltrends.com/hometheater/whatisasmarttv/ Should I get a streaming device if I already have a Smart TV? Advantages of streaming device over Smart TV apps: • Get access to more streaming services (?) (Some Smart TV’s now have app stores) • A more userfriendly interface and search system • Easier to navigate between app • Search all apps at once • Faster response (?) • A way to make old TV’s “Smart” (or Smarter) What can you do with a streaming device? • Access over 500k movies & TV shows via Hulu, Netflix, STARZ, SHOWTIME, HBO Max, Prime Video, etc.