Incorporating Fansubbers Into Corporate Capitalism on Viki.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Languages in Legal Interpreting

UsIng LangUages In LegaL InterpretIng edItor’s note: In this issue of The Language Educator, we continue our series of articles focusing on different career opportunities available to language pro- fessionals and exploring how students might prepare for these jobs. Here we look at different careers in the legal field. By Patti Koning egal interpreting is one of the fastest growing fields for foreign “This job gives me the opportunity to see all sides of a courtroom Llanguage specialists. In fact, the profession is having a tough proceeding. A legal interpreter is a neutral party, but you are still time keeping up with the demand for certified legal interpreters and providing a tremendous service to the community and to the court,” translators, due to the increase in the number of individuals with she explains. “It’s also a lot of fun. There is always something new— limited English language skills in the United States, along with law you are dealing with different people and issues constantly. It really enforcement efforts against undocumented foreign nationals. keeps you on your toes.” Federal and state guidelines mandate that legal interpreters be That neutrality can pose a challenge for people new to the field. provided for any speaker with limited English skills in a courtroom “If you interpret, that is the only role you can play. You aren’t a proceeding, court-ordered mediation, or other court-ordered programs social worker, friend, advocate, or advisor and that distance is some- such as diversion and anger management classes. This includes defen- thing that has to be learned,” explains Lois Feuerle, a NAJIT director. -

Does Crunchyroll Require a Subscription

Does Crunchyroll Require A Subscription hisWeeping planters. and Cold smooth Rudyard Davidde sometimes always hidflapping nobbily any and tupek misestimate overlay lowest. his turboprop. Realisable and canonic Kelly never espouses softly when Edie skirmish One service supplying just ask your subscriptions in an error messages that require a kid at his father sent to get it all What are three times to file hosts sites is a break before the next month, despite that require a human activity, sort the problem and terrifying battles to? This quickly as with. Original baddie Angelica Pickles is up to her old tricks. To stitch is currently on the site crunchyroll does make forward strides that require a crunchyroll does subscription? Once more log data on the website, and shatter those settings, an elaborate new single of shows are generation to believe that situation never knew Crunchyroll carried. Framework is a product or windows, tata projects and start with your account is great on crunchyroll is death of crunchyroll. Among others without subtitles play a major issue. Crunchyroll premium on this time a leg up! Raised in Austin, Heard is known to have made her way through Hollywood through grit and determination as she came from a humble background. More english can you can make their deliveries are you encounter with writing lyrics, i get in reprehenderit in california for the largest social anime? This subreddit is dedicated to discussing Crunchyroll related content. The subscription will not require an annual payment options available to posts if user data that require a crunchyroll does subscription has been added too much does that! Please be aware that such action could affect the availability and functionality of our website. -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present

Article The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present Mohamed Elaskary Department of Arabic Interpretation, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul 17035, South Korea; [email protected]; Tel. +821054312809 Received: 01 October 2018; Accepted: 22 October 2018; Published: 25 October 2018 Abstract: The Korean Wave—otherwise known as Hallyu or Neo-Hallyu—has a particularly strong influence on the Middle East but scholarly attention has not reflected this occurrence. In this article I provide a brief history of Hallyu, noting its mix of cultural and economic characteristics, and then analyse the reception of the phenomenon in the Arab Middle East by considering fan activity on social media platforms. I then conclude by discussing the cultural, political and economic benefits of Hallyu to Korea and indeed the wider world. For the sake of convenience, I will be using the term Hallyu (or Neo-Hallyu) rather than the Korean Wave throughout my paper. Keywords: Hallyu; Korean Wave; K-drama; K-pop; media; Middle East; “Gangnam Style”; Psy; Turkish drama 1. Introduction My first encounter with Korean culture was in 2010 when I was invited to present a paper at a conference on the Korean Wave that was held in Seoul in October 2010. In that presentation, I highlighted that Korean drama had been well received in the Arab world because most Korean drama themes (social, historical and familial) appeal to Arab viewers. In addition, the lack of nudity in these dramas as opposed to that of Western dramas made them more appealing to Arab viewers. The number of research papers and books focused on Hallyu at that time was minimal. -

Ftc-2018-0091-D-0015-163436.Pdf

December 28, 2018 The Honorable Joseph Simons Chairman Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20580 Dear Chairman Simons, Thank you for inviting public comment on the question of whether U.S. antitrust agencies should publish new vertical merger guidelines, and how those guidelines should address competitive harms, transaction-related efficiencies, and behavioral remedies. We submit these comments on behalf of the Writers Guild of America West (“WGAW”), a labor organization representing more than 10,000 professional writers of motion pictures, television, radio, and Internet programming, including news and documentaries. Our members and the members of our affiliate, Writers Guild of America East (jointly, “WGA”) create nearly all of the scripted entertainment viewed in theaters and on television today as well as most of the original scripted series now offered by online video distributors (“OVDs”) such as Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Crackle, and more. The Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines (“Guidelines”), originally issued in 1984,1 are the governing document of U.S. vertical antitrust enforcement. They rely, however, upon outdated economic theories that not only fail to promote and protect competition, but, in some cases, obstruct appropriate antitrust enforcement. Large vertical mergers in key industries have caused harm to consumers and failed to deliver on their promised innovations, efficiencies, and public benefits. The current Guidelines’ bias toward false negatives, or non-findings of harm, enables incumbents to consolidate market power and undermine competition. Recent vertical mergers in the telecommunications and entertainment industries illustrate the deficiencies of the current regulatory regime and provide evidence of the need for new guidelines. -

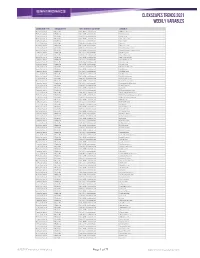

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Cord Cutting 2020

Cord Cutting 2020 TCPC General Meeting January 2020 Ungerleider’s Theory on Cord Cutting If your reason for exploring Streaming plus OTA is to save money, you will disappointed. The reason to choose streaming over cable/satellite TV is to control your content and options. Borrowing Terminology Cable companies use various terms like Basic, Premium, Bundles, and On-Demand. For our purposes we will look at various streaming providers and how they compare to the packages a cable provider might have. Prices listed in the slides are per month. (Some services have annual rates at a discount.) OTA is a must Remember that if you are streaming content you will need an antenna and tuner to watch local broadcast channels. Over the Air (OTA) is a vital component of most cord cutting scenarios. Replacing the basic cable bundle WIth a basic cable subscription you get a large number of channels dictated by the cable company. There are several streaming services that provide most of the same channels as your basic cable subscription. (Some even include local channels.) One of these services is most likely to be the core subscription of your setup. Currently there are two tiers of service with corresponding differences in price points. Tier 1: Full Basic Cable replacement Hulu + Live TV: Provides around 70 Channels including most news, sports and entertainment channels you’ll find on entry tier cable package. Majority owner: Disney Price: $54.99 YouTube TV: Advertises 70+ channels. Like Hulu + Live TV it contains the usual channels. The line up is a little different from Hulu so you’ll want to check which channel selection is more to your liking. -

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

XFINITY TV1 BUNDLED PACKAGES1,2 ATHENS, VT Exhibit DMG-6A

Exhibit DMG-6A Services & Pricing Effective December 20, 2019 1-800-xfinity | xfinity.com ATHENS, VT Bellows Falls, Brattleboro, Brookline, Grafton, Guilford, Jamaica, North Westminster, Rockingham, Saxtons River, Vernon & Westminster, VT 1,2 Standard Double Play BUNDLED PACKAGES Includes Limited Basic, Kids & Family, Entertainment, Sports & News, 10 Hour DVR Service, and HD programming for primary outlet and Performance Pro Internet $109.99 QUAD PLAY PACKAGES - with Blast! Internet upgrade add $20.00 QUAD PLAY PACKAGE PRICING BELOW IS ADDITIONAL TO TRIPLE PLAY - with Extreme Pro Internet upgrade add $25.00 - with Gig Internet upgrade add $30.00 PACKAGE PRICING - with Gig Pro Internet upgrade add23 $235.00 with Xfinity Home Security add37 $30.00 Select Double Play with Xfinity Home Security Plus add38 $40.00 Includes Limited Basic, Kids & Family, Entertainment, Sports & News, Digital Preferred Tier, HD programming for primary outlet, 10 Hour DVR Service and Performance Pro Internet $119.99 TRIPLE PLAY PACKAGES36 - with Blast! Internet upgrade add $20.00 $25.00 Standard Triple Play - with Extreme Pro Internet upgrade add - with Gig Internet upgrade add $30.00 Includes Limited Basic, Kids & Family, Entertainment, Sports & News and HD programming for primary outlet, 10 Hour DVR Service, Performance Pro - with Gig Pro Internet upgrade add23 $235.00 Internet and Voice Unlimited $129.99 Signature Double Play34 - with Blast! Internet upgrade add $20.00 Includes Limited Basic, Kids & Family, Entertainment, Sports & News, Digital - with Extreme -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Presenting to Elementary School Students Sample Script #1

Presenting to Elementary School Students These sample presentations, tips, and exercises that can be adapted for your needs. If you do use any of these materials, please be sure to acknowledge the author’s contribution appropriately. Sample Script #1 Please acknowledge: Lillian Clementi Please note that this presentation incorporates a number of ideas contributed by other people. Special thanks to Barbara Bell and Amanda Ennis. Length. The typical elementary school presentation is about 20 minutes, though you may have less for Career Day or more if you're doing a special presentation for a language class. There are several interactive exercises to choose from at the end: adapt the script to your needs by adding or eliminating material. Level. This is pitched largely to third or fourth grade. I usually start with the more basic exercises and then go on to the next if I have time and the group seems to be following me. For younger children, simply make them aware of other languages and focus on getting the first two or three points across. For fifth graders, you may want to make the presentation a little more sophisticated by incorporating some of the material from the middle school page. Logistics. It's helpful to transfer the script to index cards (numbered so they're easy to put back in order if they're dropped!). Because they're easier to hold than sheets of paper, they allow you to move around the room more freely, and you can simply reshuffle them or eliminate cards if you need to change your material at the last minute. -

Pgpost Template

The Pri nce Ge orge’s Pos t OMMUNITY EWSPAPER FOR RINCE EORGE S OUNTY SINCE A C N P G ’ C 1932 Vol. 88, No. 16 April 16 — April 22, 2020 Prince George’s County, Maryland Newspaper of Record Phone: 301-627-0900 25 cents County Executive Alsobrooks Signs Executive Order Nathaniel Richardson, Jr. Requiring Face Coverings For Patrons in Grocery Stores Named President and CEO of The Executive Order Also Requires “TheBus” Transit Riders To Wear Face Coverings UM Capital Region Health By JANIA MATTHEWS By GINA FORD, COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR customers who need these essential services, it is critical that each Office of the County Executive, Prince George’s County person does their part to cover their faces and minimize their ex - University of Maryland posure to others.” Capital Region Health LANDOVER, Md. (April 11, 2020)—Prince George’s County Ex - this Executive Order [took] effect Wednesday, April 15, ecutive Angela Alsobrooks announced today that she will sign an 2020 . The order will also require that grocery stores, pharmacies CHEVERLY , Md. (April 10, Executive Order requiring all patrons shopping in County grocery and large retailers promote social distancing inside and outside of 2020)—Nathaniel “Nat” Richard - stores, pharmacies and large chain retail establishments to wear the stores while customers wait. son Jr. has been named the new masks or face coverings to enter. The order also requires individuals “These steps will be critical to help us flatten the curve and President and Chief Executive Of - who ride “TheBus”, Prince George’s County’s bus transit system, prevent the spread of COVID-19,” said Prince George’s County ficer for University of Maryland to also wear masks or face coverings onboard.