A Generalization of the Trichotomy Principle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Elementary Set Theory

1 Elementary Set Theory Notation: fg enclose a set. f1; 2; 3g = f3; 2; 2; 1; 3g because a set is not defined by order or multiplicity. f0; 2; 4;:::g = fxjx is an even natural numberg because two ways of writing a set are equivalent. ; is the empty set. x 2 A denotes x is an element of A. N = f0; 1; 2;:::g are the natural numbers. Z = f:::; −2; −1; 0; 1; 2;:::g are the integers. m Q = f n jm; n 2 Z and n 6= 0g are the rational numbers. R are the real numbers. Axiom 1.1. Axiom of Extensionality Let A; B be sets. If (8x)x 2 A iff x 2 B then A = B. Definition 1.1 (Subset). Let A; B be sets. Then A is a subset of B, written A ⊆ B iff (8x) if x 2 A then x 2 B. Theorem 1.1. If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A then A = B. Proof. Let x be arbitrary. Because A ⊆ B if x 2 A then x 2 B Because B ⊆ A if x 2 B then x 2 A Hence, x 2 A iff x 2 B, thus A = B. Definition 1.2 (Union). Let A; B be sets. The Union A [ B of A and B is defined by x 2 A [ B if x 2 A or x 2 B. Theorem 1.2. A [ (B [ C) = (A [ B) [ C Proof. Let x be arbitrary. x 2 A [ (B [ C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B [ C iff x 2 A or (x 2 B or x 2 C) iff x 2 A or x 2 B or x 2 C iff (x 2 A or x 2 B) or x 2 C iff x 2 A [ B or x 2 C iff x 2 (A [ B) [ C Definition 1.3 (Intersection). -

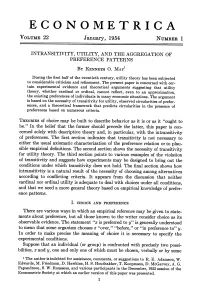

Intransitivity, Utility, and the Aggregation of Preference Patterns

ECONOMETRICA VOLUME 22 January, 1954 NUMBER 1 INTRANSITIVITY, UTILITY, AND THE AGGREGATION OF PREFERENCE PATTERNS BY KENNETH 0. MAY1 During the first half of the twentieth century, utility theory has been subjected to considerable criticism and refinement. The present paper is concerned with cer- tain experimental evidence and theoretical arguments suggesting that utility theory, whether cardinal or ordinal, cannot reflect, even to an approximation, the existing preferences of individuals in many economic situations. The argument is based on the necessity of transitivity for utility, observed circularities of prefer- ences, and a theoretical framework that predicts circularities in the presence of preferences based on numerous criteria. THEORIES of choice may be built to describe behavior as it is or as it "ought to be." In the belief that the former should precede the latter, this paper is con- cerned solely with descriptive theory and, in particular, with the intransitivity of preferences. The first section indicates that transitivity is not necessary to either the usual axiomatic characterization of the preference relation or to plau- sible empirical definitions. The second section shows the necessity of transitivity for utility theory. The third section points to various examples of the violation of transitivity and suggests how experiments may be designed to bring out the conditions under which transitivity does not hold. The final section shows how intransitivity is a natural result of the necessity of choosing among alternatives according to conflicting criteria. It appears from the discussion that neither cardinal nor ordinal utility is adequate to deal with choices under all conditions, and that we need a more general theory based on empirical knowledge of prefer- ence patterns. -

Natural Numerosities of Sets of Tuples

TRANSACTIONS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 367, Number 1, January 2015, Pages 275–292 S 0002-9947(2014)06136-9 Article electronically published on July 2, 2014 NATURAL NUMEROSITIES OF SETS OF TUPLES MARCO FORTI AND GIUSEPPE MORANA ROCCASALVO Abstract. We consider a notion of “numerosity” for sets of tuples of natural numbers that satisfies the five common notions of Euclid’s Elements, so it can agree with cardinality only for finite sets. By suitably axiomatizing such a no- tion, we show that, contrasting to cardinal arithmetic, the natural “Cantorian” definitions of order relation and arithmetical operations provide a very good algebraic structure. In fact, numerosities can be taken as the non-negative part of a discretely ordered ring, namely the quotient of a formal power series ring modulo a suitable (“gauge”) ideal. In particular, special numerosities, called “natural”, can be identified with the semiring of hypernatural numbers of appropriate ultrapowers of N. Introduction In this paper we consider a notion of “equinumerosity” on sets of tuples of natural numbers, i.e. an equivalence relation, finer than equicardinality, that satisfies the celebrated five Euclidean common notions about magnitudines ([8]), including the principle that “the whole is greater than the part”. This notion preserves the basic properties of equipotency for finite sets. In particular, the natural Cantorian definitions endow the corresponding numerosities with a structure of a discretely ordered semiring, where 0 is the size of the emptyset, 1 is the size of every singleton, and greater numerosity corresponds to supersets. This idea of “Euclidean” numerosity has been recently investigated by V. -

Reverse Mathematics, Trichotomy, and Dichotomy

Reverse mathematics, trichotomy, and dichotomy Fran¸coisG. Dorais, Jeffry Hirst, and Paul Shafer Department of Mathematical Sciences Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608 February 20, 2012 Abstract Using the techniques of reverse mathematics, we analyze the log- ical strength of statements similar to trichotomy and dichotomy for sequences of reals. Capitalizing on the connection between sequential statements and constructivity, we find computable restrictions of the statements for sequences and constructive restrictions of the original principles. 1 Axiom systems and encoding reals We will examine several statements about real numbers and sequences of real numbers in the framework of reverse mathematics and in some formalizations of weak constructive analysis. From reverse mathematics, we will concentrate on the axiom systems RCA0, WKL0, and ACA0, which are described in detail by Simpson [8]. Very roughly, RCA0 is a subsystem of second order arith- metic incorporating ordered semi-ring axioms, a restricted form of induction, 0 and comprehension for ∆1 definable sets. The axiom system WKL0 appends K¨onig'stree lemma restricted to 0{1 trees, and the system ACA0 appends a comprehension scheme for arithmetically definable sets. ACA0 is strictly stronger than WKL0, and WKL0 is strictly stronger than RCA0. We will also make use of several formalizations of subsystems of con- structive analysis, all variations of E-HA!, which is intuitionistic arithmetic 1 (Heyting arithmetic) in all finite types with an extensionality scheme. Unlike the reverse mathematics systems which use classical logic, these constructive systems omit the law of the excluded middle. For example, we will use ex- tensions of E\{HA!, a form of Heyting arithmetic with primitive recursion restricted to type 0 objects, and induction restricted to quantifier free for- mulas. -

Some Set Theory We Should Know Cardinality and Cardinal Numbers

SOME SET THEORY WE SHOULD KNOW CARDINALITY AND CARDINAL NUMBERS De¯nition. Two sets A and B are said to have the same cardinality, and we write jAj = jBj, if there exists a one-to-one onto function f : A ! B. We also say jAj · jBj if there exists a one-to-one (but not necessarily onto) function f : A ! B. Then the SchrÄoder-BernsteinTheorem says: jAj · jBj and jBj · jAj implies jAj = jBj: SchrÄoder-BernsteinTheorem. If there are one-to-one maps f : A ! B and g : B ! A, then jAj = jBj. A set is called countable if it is either ¯nite or has the same cardinality as the set N of positive integers. Theorem ST1. (a) A countable union of countable sets is countable; (b) If A1;A2; :::; An are countable, so is ¦i·nAi; (c) If A is countable, so is the set of all ¯nite subsets of A, as well as the set of all ¯nite sequences of elements of A; (d) The set Q of all rational numbers is countable. Theorem ST2. The following sets have the same cardinality as the set R of real numbers: (a) The set P(N) of all subsets of the natural numbers N; (b) The set of all functions f : N ! f0; 1g; (c) The set of all in¯nite sequences of 0's and 1's; (d) The set of all in¯nite sequences of real numbers. The cardinality of N (and any countable in¯nite set) is denoted by @0. @1 denotes the next in¯nite cardinal, @2 the next, etc. -

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4 Jeremy Avigad, Robert Y. Lewis, and Floris van Doorn Sep 10, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Mathematical Proof ............................................ 1 1.2 Symbolic Logic .............................................. 2 1.3 Interactive Theorem Proving ....................................... 4 1.4 The Semantic Point of View ....................................... 5 1.5 Goals Summarized ............................................ 6 1.6 About this Textbook ........................................... 6 2 Propositional Logic 7 2.1 A Puzzle ................................................. 7 2.2 A Solution ................................................ 7 2.3 Rules of Inference ............................................ 8 2.4 The Language of Propositional Logic ................................... 15 2.5 Exercises ................................................. 16 3 Natural Deduction for Propositional Logic 17 3.1 Derivations in Natural Deduction ..................................... 17 3.2 Examples ................................................. 19 3.3 Forward and Backward Reasoning .................................... 20 3.4 Reasoning by Cases ............................................ 22 3.5 Some Logical Identities .......................................... 23 3.6 Exercises ................................................. 24 4 Propositional Logic in Lean 25 4.1 Expressions for Propositions and Proofs ................................. 25 4.2 More commands ............................................ -

Preliminary Knowledge on Set Theory

Huan Long Shanghai Jiao Tong University Basic set theory Relation Function Spring 2018 Georg Cantor(1845-1918) oGerman mathematician o Founder of set theory Bertrand Russell(1872-1970) oBritish philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic. Ernst Zermelo(1871-1953) oGerman mathematician, foundations of mathematics and hence on philosophy David Hilbert (1862-1943) o German mathematicia, one of the most influential and universal mathematicians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Kurt Gödel(1906-1978) oAustrian American logician, mathematician, and philosopher. ZFC not ¬CH . Paul Cohen(1934-2007)⊢ oAmerican mathematician, 1963: ZFC not CH,AC . Spring 2018 ⊢ Spring 2018 By Georg Cantor in 1870s: A set is an unordered collection of objects. ◦ The objects are called the elements, or members, of the set. A set is said to contain its elements. Notation: ◦ Meaning that: is an element of the set A, or, Set A contains ∈ . Important: ◦ Duplicates do not matter. ◦ Order does not matter. Spring 2018 a∈A a is an element of the set A. a A a is NOT an element of the set A. Set of sets {{a,b},{1, 5.2}, k} ∉ the empty set, or the null set, is set that has no elements. A B subset relation. Each element of A is also an element of B. ∅ A=B equal relation. A B and B A. ⊆ A B ⊆ ⊆ A B strict subset relation. If A B and A B ≠ |A| cardinality of a set, or the number of distinct elements. ⊂ ⊆ ≠ Venn Diagram V U A B U Spring 2018 { , , , } a {{a}} ∈ ∉ {{ }} ∅ ∉∅ {3,4,5}={5,4,3,4} ∅ ∈ ∅ ∈ ∅ S { } ∅⊆ S S ∅ ⊂ ∅ |{3, 3, 4, {2, 3},{1,2,{f}} }|=4 ⊆ Spring 2018 Union Intersection Difference Complement Symmetric difference Power set Spring 2018 Definition Let A and B be sets. -

Learnability Can Be Independent of ZFC Axioms: Explanations and Implications

Learnability Can Be Independent of ZFC Axioms: Explanations and Implications (William) Justin Taylor Department of Computer Science University of Wisconsin - Madison Madison, WI 53715 [email protected] September 19, 2019 1 Introduction Since Gödel proved his incompleteness results in the 1930s, the mathematical community has known that there are some problems, identifiable in mathemat- ically precise language, that are unsolvable in that language. This runs the gamut between very abstract statements like the existence of large cardinals, to geometrically interesting statements, like the parallel postulate.1 One, in particular, is important here: The Continuum Hypothesis, CH, says that there are no infinite cardinals between the cardinality of the natural numbers and the cardinality of the real numbers. In Ben-David et al.’s "Learnability Can Be Undecidable," they prove an independence2 result in theoretical machine learning. In particular, they define a new type of learnability, called Estimating The Maximum (EMX) learnability. They argue that this type of learnability fits in with other notions such as PAC learnability, Vapnik’s statistical learning setting, and other general learning settings. However, using some set-theoretic techniques, they show that some learning problems in the EMX setting are independent of ZFC. Specifically they prove that ZFC3 cannot prove or disprove EMX learnability of the finite subsets arXiv:1909.08410v1 [cs.LG] 16 Sep 2019 on the [0,1] interval. Moreover, the way they prove it shows that there can be no characteristic dimension, in the sense defined in 2.1, for EMX; and, hence, for general learning settings. 1Which states that, in a plane, given a line and a point not on it, at most one line parallel to the given line can be drawn through the point. -

Math 7409 Lecture Notes 10 Posets and Lattices a Partial Order on a Set

Math 7409 Lecture Notes 10 Posets and Lattices A partial order on a set X is a relation on X which is reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive. A set with a partial order is called a poset. If in a poset x < y and there is no z so that x < z < y, then we say that y covers x (or sometimes that x is an immediate predecessor of y). Hasse diagrams of posets are graphs of the covering relation with all arrows pointed down. A total order (or linear order) is a partial order in which every two elements are comparable. This is equivalent to satisfying the law of trichotomy. A maximal element of a poset is an element x such that if x ≤ y then y = x. Note that there may be more than one maximal element. Lemma: Any (non-empty) finite poset contains a maximal element. In a poset, z is a lower bound of x and y if z ≤ x and z ≤ y. A greatest lower bound (glb) of x and y is a maximal element of the set of lower bounds. By the lemma, if two elements of finite poset have a lower bound then they have a greatest lower bound, but it may not be unique. Upper bounds and least upper bounds are defined similarly. [Note that there are alternate definitions of glb, and in some versions a glb is unique.] A (finite) lattice is a poset in which each pair of elements has a unique greatest lower bound and a unique least upper bound. -

Expected Scott-Suppes Utility Representation

Intransitive Indifference Under Uncertainty: Expected Scott-Suppes Utility Representation Nuh Ayg¨unDalkıran¦ Oral Ersoy Dokumacı: Tarık Kara ; October 23, 2017 Abstract We study preferences with intransitive indifference under uncer- tainty. Our primitives are semiorders and we are interested in their Scott-Suppes representations. We obtain a Scott-Suppes representa- tion theorem in the spirit of the expected utility theorem of von Neu- mann and Morgenstern (1944). Our representation offers a decision theoretical interpretation for epsilon equilibrium. Keywords: Semiorder, Instransitive Indifference, Uncertainty, Scott-Suppes Representation, Expected Utility. ¦Bilkent University, Department of Economics; [email protected] :University of Rochester, Department of Economics; [email protected] ;Bilkent University, Department of Economics; [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Intransitive Indifference and Semiorders . 3 1.2 Expected Utility Theory . 4 2 Related Literature 5 3 Preliminaries 6 3.1 Semiorders . 6 3.2 Continuity . 12 3.3 Independence . 16 3.4 Utility Representations . 17 4 Expected Scott-Suppes Utility Representation 18 4.1 The Main Result . 19 4.2 Uniqueness . 25 4.3 Independence of the Axioms . 25 5 On Epsilon Equilibrium 32 6 Conclusion 34 7 Appendix 36 References 38 List of Figures 1 Example 1 . 8 2 Example 3 . 14 3 Example 3 . 14 4 Example 4 . 15 5 Example 5 . 26 2 1 Introduction 1.1 Intransitive Indifference and Semiorders The standard rationality assumption in economic theory states that indi- viduals have or should have transitive preferences.1 A common argument to support the transitivity requirement is that, if individuals do not have tran- sitive preferences, then they are subject to money pumps (Fishburn, 1991). -

Reverse Mathematics, Trichotomy, and Dichotomy

Reverse mathematics, trichotomy, and dichotomy Fran¸coisG. Dorais, Jeffry Hirst∗, and Paul Shafer Department of Mathematical Sciences Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608 August 25, 2011 Abstract Using the techniques of reverse mathematics, we analyze the log- ical strength of statements similar to trichotomy and dichotomy for sequences of reals. Capitalizing on the connection between sequen- tial statements and constructivity, we use computable restrictions of the statements to indicate forms provable in formal systems of weak constructive analysis. Our goal is to demonstrate that reverse math- ematics can assist in the formulation of constructive theorems. 1 Axiom systems and encoding reals We will examine several statements about real numbers and sequences of real numbers in the framework of reverse mathematics and in some formalizations of weak constructive analysis. From reverse mathematics, we will concentrate on the axiom systems RCA0, WKL0, and ACA0, which are described in detail by Simpson [6]. Very roughly, RCA0 is a subsystem of second order arith- metic incorporating ordered semi-ring axioms, a restricted form of induction, 0 and comprehension for ∆1 definable sets. The axiom system WKL0 appends ∗Jeffry Hirst was supported by grant (ID#20800) from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. 1 K¨onig'stree lemma restricted to 0-1 trees, and the system ACA0 appends a comprehension scheme for arithmetically definable sets. ACA0 is strictly stronger than WKL0, and WKL0 is strictly stronger than RCA0. We will also make use of several formalizations of subsystems of con- structive analysis, all variations of E-HA!, which is intuitionistic arithmetic (Heyting arithmetic) in all finite types with an extensionality scheme. -

Notes on the Integers

MATH 324 Summer 2011 Elementary Number Theory Notes on the Integers Properties of the Integers The set of all integers is the set Z = ; 5; 4; 3; 2; 1; 0; 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; ; {· · · − − − − − · · · g and the subset of Z given by N = 0; 1; 2; 3; 4; ; f · · · g is the set of nonnegative integers (also called the natural numbers or the counting numbers). We assume that the notions of addition (+) and multiplication ( ) of integers have been defined, and note that Z with these two binary operations satisfy the following. · Axioms for Integers Closure Laws: if a; b Z; then • 2 a + b Z and a b Z: 2 · 2 Commutative Laws: if a; b Z; then • 2 a + b = b + a and a b = b a: · · Associative Laws: if a; b; c Z; then • 2 (a + b) + c = a + (b + c) and (a b) c = a (b c): · · · · Distributive Law: if a; b; c Z; then • 2 a (b + c) = a b + a c and (a + b) c = a c + b c: · · · · · · Identity Elements: There exist integers 0 and 1 in Z; with 1 = 0; such that • 6 a + 0 = 0 + a = a and a 1 = 1 a = a · · for all a Z: 2 Additive Inverse: For each a Z; there is an x Z such that • 2 2 a + x = x + a = 0; x is called the additive inverse of a or the negative of a; and is denoted by a: − The set Z together with the operations of + and satisfying these axioms is called a commutative ring with identity.