Camille Holbrook Warbington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kyankwanzi Survey Report 2017

GROUND SURVEY FOR MEDIUM - LARGE MAMMALS IN KYANKWANZI CONCESSION AREA Report by F. E. Kisame, F. Wanyama, G. Basuta, I. Bwire and A. Rwetsiba, ECOLOGICAL MONITORING AND RESEARCH UNIT UGANDA WILDLIFE AUTHORITY 2018 1 | P a g e Contents Summary.........................................................................................................................4 1.0. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................5 1.1. Survey Objectives.....................................................................................................6 2.0. DESCRIPTION OF THE SURVEY AREA ..........................................................6 2.2. Location and Size .....................................................................................................7 2.2. Climate.....................................................................................................................7 2.3 Relief and Vegetation ................................................................................................8 3.0. METHOD AND MATERIALS..............................................................................9 Plate 1. Team leader and GPS person recording observations in the field.........................9 3.1. Survey design .........................................................................................................10 4.0. RESULTS .............................................................................................................10 4.1. Fauna......................................................................................................................10 -

Habitats Map of Distributions of Key Wild Animal Species of Gambella National Park

www.ijird.com April, 2015 Vol 4 Issue 4 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Habitats Map of Distributions of Key Wild Animal Species of Gambella National Park Gatluak Gatkoth Rolkier Ph.D. Candidate, Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, Building Construction and City, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Kumelachew Yeshitela Chair Holder (Head), Ecosystem Planning and Management, Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, Building Construction and City, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Ruediger Prasse Professor, Department of Environmental Planning, Leibniz Gottferd University of Hannover, Herrenhauser Hannover, Germany Abstract: Lack of information on habitat map of Gambella National Park had resulted in problems of identification for abundance and distribution of studied wild animal species per their habitats use in the park. Therefore, the information gathered for habitat map of key studied wild animal species of the Park, was used to fill the knowledge gap on their most preference habitat types of the Park. The specific objectives of this research were to determine the abundance and distribution of studied wild animal species in each classified habitat, to determine the density of studied wild animal species of the Park. The data were collected by lines transect method, which were conducted in both dry and wet seasons. Accordingly, six men in a queue were involved in the surveys. The front man was using a compass to lead the team in a straight line along the transects and measure the bearing of track of animals, two men were positioned in the middle and one was observed on the right side of transects while the other observed on the left side of transects and rear man was used GPS receiver and keep recording of information on observed wild animal species. -

Benin 2019 - 2020

BENIN 2019 - 2020 West African Savannah Buffalo Western Roan Antelope For more than twenty years, we have been organizing big game safaris in the north of the country on the edge of the Pendjari National Park, in the Porga hunting zone. The hunt is physically demanding and requires hunters to be in good physical condition. It is primary focused on hunting Roan Antelopes, West Savannah African Buffaloes, Western Kobs, Nagor Reedbucks, Western Hartebeests… We shoot one good Lion every year, hunted only by tracking. Baiting is not permitted. Accommodation is provided in a very confortable tented camp offering a spectacular view on the bush.. Hunting season: from the beginning of January to mid-May. - 6 days safari: each hunter can harvest 1 West African Savannah Buffalo, 1 Roan Antelope or 1 Western Hartebeest, 1 Nagor Reedbuck or 1 Western Kob, 1 Western Bush Duiker, 1 Red Flanked Duiker, 1 Oribi, 1 Harnessed Bushbuck, 1 Warthog and 1 Baboon. - 13 and 20 days safari: each hunter can harvest 1 Lion (if available at the quota), 1 West African Savannah Buffalo, 1 Roan Antelope, 1 Sing Sing Waterbuck, 1 Hippopotamus, 1 Western Hartebeest, 1 Nagor Reedbuck, 1 Western Kob, 1 Western Bush Duiker, 1 Red Flanked Duiker, 1 Oribi, 1 Harnessed Bushbuck, 1 Warthog and 1 Baboon. Prices in USD: Price of the safari per person 6 hunting days 13 hunting days 20 hunting days 2 Hunters x 1 Guide 8,000 16,000 25,000 1 Hunter x 1 Guide 11,000 24,000 36,000 Observer 3,000 4,000 5,000 The price of the safari includes: - Meet and greet plus assistance at Cotonou airport (Benin), - Transfer from Cotonou to the hunting area and back by car, - The organizing of your safari with 4x4 vehicles, professional hunters, trackers, porters, skinners, - Full board accommodation and drinks at the hunting camp. -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa's Sudano-Sahel

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Transhumant Pastoralism in Africa’s Sudano-Sahel The interface of conservation, security, and development Mbororo pastoralists illegally grazing cattle in Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Credit: Naftali Honig/African Parks Africa’s Sudano-Sahel is a distinct bioclimatic and ecological zone made up of savanna and savanna-forest transition Program Priorities habitat that covers approximately 7.7 million square kilometers of the continent. Rich in species diversity, the • Increased data gathering and assessment of core Sudano-Sahel region represents one of the last remaining natural resource assets across the Sudano-Sahel region. intact wilderness areas in the world, and is a high priority • Efficient data-sharing, analysis, and dissemination for wildlife conservation. It is home to an array of antelope between relevant stakeholders spanning conservation, species such as giant eland and greater kudu, in addition to security, and development sectors, and in collaboration African wild dog, Kordofan giraffe, African elephant, African with rural agriculturalists and pastoralists. lion, leopard, and giant pangolin. • Enhancement and promotion of multi-level This region is also home to many rural communities who rely governance approaches to resolve conflict and stabilize on the landscape’s natural resources, including pastoralists, transhumance corridors. whose livelihoods and cultural identity are centered around • Continuation and expansion of strategic investments in strategic mobility to access seasonally available grazing the network of priority protected areas and their buffer resources and water. Instability, climate change, and zones across the Sudano-Sahel, in order to improve increasing pressures from unsustainable land use activities security for both wildlife and surrounding communities. -

Oribi Conservation

www.forestryexplained.co.za SAVING SPECIES: ORIBI CONSERVATION Forestry Explained: Our Conservation Legacy Introducing the Oribi: South Africa’s most endangered antelope All photos courtesy of the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) Slender, graceful and timid, the Oribi fact file: Oribi (Ourebia ourebi) is one of - Height: 50 – 67 cm South Africa’s most captivating antelope. Sadly, the Oribi’s - Weight: 12 – 22 kg future in South Africa is - Length: 92 -110 cm uncertain. Already recognised - Colour: Yellowish to orange-brown back as endangered in South Africa, its numbers are still declining. and upper chest, white rump, belly, chin and throat. Males have slender Oribi are designed to blend upright horns. into their surroundings and are - Habitat: Grassland region of South Africa, able to put on a turn of speed when required, making them KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape, Free State perfectly adapted for life on and Mpumalanga. open grassland plains. - Diet: Selective grazers. GRASSLANDS: LINKING FORESTRY TO WETLANDS r ecosystems rive are Why is wetland conservation so ’s fo ica un r d important to the forestry industry? Af in h g t r u a o s of S s % Sou l 8 th f a 6 A o n is fr d o ic s .s a . 28% ' . s 2 . 497,100 ha t i 4 SAVANNAH m b e r p l Why they are South Africa’s most endangereda n t a 4% t i 65,000 ha o n FYNBOS s The once expansive Grassland Biome has halved in. size over the last few decades, with around 50% being irreversibly transformed as a result of 68% habitat destruction. -

Towards Snow Leopard Prey Recovery: Understanding the Resource Use Strategies and Demographic Responses of Bharal Pseudois Nayaur to Livestock Grazing and Removal

Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal Final project report submitted by Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore Post-graduate Program in Wildlife Biology and Conservation, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Wildlife Conservation Society –India program, Bangalore, India To Snow Leopard Conservation Grant Program January 2009 Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal. 1. Executive Summary: Decline of wild prey populations in the Himalayan region, largely due to competition with livestock, has been identified as one of the main threats to the snow leopard Uncia uncia. Studies show that bharal Pseudois nayaur diet is dominated by graminoids during summer, but the proportion of graminoids declines in winter. We explore the causes for the decline of graminoids from bharal winter diet and resulting implications for bharal conservation. We test the predictions generated by two alternative hypotheses, (H1) low graminoid availability caused by livestock grazing during winter causes bharal to include browse in their diet, and, (H2) bharal include browse, with relatively higher nutrition, to compensate for the poor quality of graminoids during winter. Graminoid availability was highest in areas without livestock grazing, followed by areas with moderate and intense livestock grazing. Graminoid quality in winter was relatively lower than that of browse, but the difference was not statistically significant. Bharal diet was dominated by graminoids in areas with highest graminoid availability. Graminoid contribution to bharal diet declined monotonically with a decline in graminoid availability. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

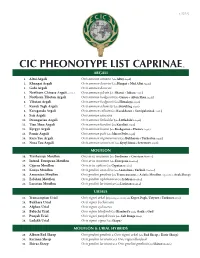

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Redalyc.ECOLOGICAL STRATEGIES and IMPACT of WILD BOAR IN

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Cuevas, M. Fernanda; Ojeda, Ricardo A.; Jaksic, Fabian M. ECOLOGICAL STRATEGIES AND IMPACT OF WILD BOAR IN PHYTOGEOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF ARGENTINA WITH EMPHASIS ON ARIDLANDS Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 23, núm. 2, 2016, pp. 239-254 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45750282004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 23:239-254, Mendoza, 2016 Copyright ©SAREM, 2016 http://www.sarem.org.ar Versión impresa ISSN 0327-9383 http://www.sbmz.com.br Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 Sección Especial MAMÍFEROS EXÓTICOS INVASORES ECOLOGICAL STRATEGIES AND IMPACT OF WILD BOAR IN PHYTOGEOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF ARGENTINA WITH EMPHASIS ON ARIDLANDS M. Fernanda Cuevas1, Ricardo A. Ojeda1 and Fabian M. Jaksic2 1 Grupo de Investigaciones de la Biodiversidad (GiB), IADIZA, CCT Mendoza CONICET, CC 507, 5500 Mendoza, Argentina. [Correspondence: <[email protected]>]. 2 Centro de Ecología Aplicada y Sustentabilidad (CAPES), Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Casilla 114-D, Santiago, Chile ABSTRACT. Wild boar is an invasive species introduced to Argentina for sport hunting purposes. Here, this spe- cies is present in at least 8 phytogeographic provinces but we only have information in four of them (Pampean grassland, Espinal, Subantarctic and Monte Desert). We review the ecological strategies and impact of wild boar on ecosystem processes in these different phytogeographic provinces and identify knowledge gaps and research priorities for a better understanding of this invasive species in Argentina. -

Reproductive Seasonality in Captive Wild Ruminants: Implications for Biogeographical Adaptation, Photoperiodic Control, and Life History

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Reproductive seasonality in captive wild ruminants: implications for biogeographical adaptation, photoperiodic control, and life history Zerbe, Philipp Abstract: Zur quantitativen Beschreibung der Reproduktionsmuster wurden Daten von 110 Wildwiederkäuer- arten aus Zoos der gemässigten Zone verwendet (dabei wurde die Anzahl Tage, an denen 80% aller Geburten stattfanden, als Geburtenpeak-Breite [BPB] definiert). Diese Muster wurden mit verschiede- nen biologischen Charakteristika verknüpft und mit denen von freilebenden Tieren verglichen. Der Bre- itengrad des natürlichen Verbreitungsgebietes korreliert stark mit dem in Menschenobhut beobachteten BPB. Nur 11% der Spezies wechselten ihr reproduktives Muster zwischen Wildnis und Gefangenschaft, wobei für saisonale Spezies die errechnete Tageslichtlänge zum Zeitpunkt der Konzeption für freilebende und in Menschenobhut gehaltene Populationen gleich war. Reproduktive Saisonalität erklärt zusätzliche Varianzen im Verhältnis von Körpergewicht und Tragzeit, wobei saisonalere Spezies für ihr Körpergewicht eine kürzere Tragzeit aufweisen. Rückschliessend ist festzuhalten, dass Photoperiodik, speziell die abso- lute Tageslichtlänge, genetisch fixierter Auslöser für die Fortpflanzung ist, und dass die Plastizität der Tragzeit unterstützend auf die erfolgreiche Verbreitung der Wiederkäuer in höheren Breitengraden wirkte. A dataset on 110 wild ruminant species kept in captivity in temperate-zone zoos was used to describe their reproductive patterns quantitatively (determining the birth peak breadth BPB as the number of days in which 80% of all births occur); then this pattern was linked to various biological characteristics, and compared with free-ranging animals. Globally, latitude of natural origin highly correlates with BPB observed in captivity, with species being more seasonal originating from higher latitudes.