New Perspectives on Meroitic Subsistence and Settlement Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct 14 C Dating of Early and Mid-Holocene Saharan Pottery Lamia Messili, Jean-François Saliège, Jean Broutin, Erwan Messager, Christine Hatté, Antoine Zazzo

Direct 14 C Dating of Early and Mid-Holocene Saharan Pottery Lamia Messili, Jean-François Saliège, Jean Broutin, Erwan Messager, Christine Hatté, Antoine Zazzo To cite this version: Lamia Messili, Jean-François Saliège, Jean Broutin, Erwan Messager, Christine Hatté, et al.. Direct 14 C Dating of Early and Mid-Holocene Saharan Pottery. Radiocarbon, University of Arizona, 2013, 55 (3), pp.1391-1402. 10.1017/S0033822200048323. hal-02351870 HAL Id: hal-02351870 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02351870 Submitted on 30 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DIRECT 14C DATING OF EARLY AND MID-HOLOCENE SAHARAN POTTERY Lamia Messili1 • Jean-François Saliège2,† • Jean Broutin3 • Erwan Messager4 • Christine Hatté5 • Antoine Zazzo2 ABSTRACT. The aim of this study is to directly radiocarbon date pottery from prehistoric rock-art shelters in the Tassili n’Ajjer (central Sahara). We used a combined geochemical and microscopic approach to determine plant material in the pot- tery prior to direct 14C dating. The ages obtained range from 5270 ± 35 BP (6276–5948 cal BP) to 8160 ± 45 BP (9190–9015 cal BP), and correlate with the chronology derived from pottery typology. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

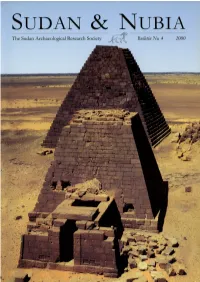

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Seleima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

Archaeological Park Or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage At

Égypte/Monde arabe 5-6 | 2009 Pratiques du Patrimoine en Égypte et au Soudan Archaeological Park or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage at Naqa in Sudan Parc archéologique ou « Disneyland » ? Conflits d’intérêts sur le patrimoine à Naqa au Soudan Ida Dyrkorn Heierland Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ema/2908 DOI: 10.4000/ema.2908 ISSN: 2090-7273 Publisher CEDEJ - Centre d’études et de documentation économiques juridiques et sociales Printed version Date of publication: 22 December 2009 Number of pages: 355-380 ISBN: 2-905838-43-4 ISSN: 1110-5097 Electronic reference Ida Dyrkorn Heierland, « Archaeological Park or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage at Naqa in Sudan », Égypte/Monde arabe [Online], Troisième série, Pratiques du Patrimoine en Égypte et au Soudan, Online since 31 December 2010, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/ema/2908 ; DOI : 10.4000/ema.2908 © Tous droits réservés IDA DYRKORN HEIERLAND ABSTRACT / RÉSUMÉ ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK OR “DISNEYLAND”? CONFLICTING INTERESTS ON HERITAGE AT NAQA IN SUDAN The article explores agencies and interests on different levels of scale permeat- ing the constituting, management and use of Sudan’s archaeological heritage today as seen through the case of Naqa. Securing the position of “unique” and “unspoiled sites”, the archaeological community and Sudanese museum staff seem to emphasize the archaeological heritage as an important means for constructing a national identity among Sudanese in general. The government, on the other hand, is mainly concerned with the World Heritage nomination as a possible way to promote Sudan’s global reputation and accelerate the economic exploitation of the most prominent archaeo- logical sites. -

Humans and Water in Desert “Refugium” Areas: Palynological Evidence of Climate Oscillations and Cultural Developments in Early and Mid-Holocene Saharan Edges

Volume VI ● Issue 2/2015 ● Pages 151–160 INTERDISCIPLINARIA ARCHAEOLOGICA NATURAL SCIENCES IN ARCHAEOLOGY homepage: http://www.iansa.eu VI/2/2015 Humans and Water in Desert “Refugium” Areas: Palynological Evidence of Climate Oscillations and Cultural Developments in Early and Mid-Holocene Saharan Edges Anna Maria Mercuria, Assunta Florenzanoa*, Carlo Giraudib, Elena A. A. Garceac a Laboratorio di Palinologia e Paleobotanica, Dipartimento di Scienze della Vita, Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, viale Caduti in Guerra 127, 41121 Modena, MO, Italy bENEA C. R. Saluggia, Strada per Crescentino 41, 13040 Saluggia, VC, Italy cDipartimento di Lettere e Filosofia, Università di Cassino e del Lazio Meridionale, via Zamosch 43, 03043 Cassino, FR, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Saharan anthropic deposits from archaeological sites, located along wadis or close to lakes, and Received: 30th April 2015 sedimentary sequences from permanent and dried basins demonstrate that water has always been Accepted: 21st December 2015 an attractive environmental feature, especially during periods of drought. This paper reports on two very different examples of Holocene sites where “humans and water” coexisted during dry periods, Key words: as observed by stratigraphic, archaeological and palynological evidence. Independent research was palaeoecology carried out on the Jefara Plain (Libya, 32°N) and the Gobero area (Niger, 17°N), at the extreme pollen northern and southern limits of the Sahara, respectively. wet habitats The histories of the Jefara and Gobero areas, as revealed by the archaeological and palaeoenvironmen- archaeology tal reconstructions, suggest that these areas were likely to have been visited and exploited for a long climate change time, acting as anthropic refugia, and therefore they have been profoundly transformed. -

Saharan Rock Art. Archaeology of Tassilian Pastoral Iconography. by Augustin F

BOOK REVIEW Saharan Rock Art. Archaeology of Tassilian Pastoral Iconography. By Augustin F. C. Holl. African Archaeology Series. AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, 2004, 192 pages. ISBN Paperback 0-7591-0605-3. Price: UK£ 22.95. The rock art of the Sahara is world class, but it series of vignettes that correspond to the annual has tended to be ignored by rock art specialists out- rhythms of pastoral transhumant life. The two panels side Saharan studies. This was underlined by omission are suggested as a narrative in the form of an allegory of any mention of Saharan art in CHIPPINDALE & or play in six acts. Act I (or Composition I) has five TAÇONs (1998) edited volume on world rock art. The scenes that deal with arrival at a camp site, setting up reasons for this may be partially due to most Saharan camp and watering the animals. Act II has three scenes rock art researchers being either French or Italian, but that deal with transit to a new camp. Act III is the new more probably due to the history of work being limited camp site that anticipates some important event, which to dating sequences (MUZZOLINI 1993) and concentra- is suggested as being gift-giving and the birth of a tion on purely collecting data to contrast styles new child. Act IV is the continuation of camp life into (SANSONI 1994). This has meant that theoretical frame- the dry season, but is seen as a metaphor for life works have tended to be abstract and general, mostly events and the new generation. -

Assessment of Groundwater Potentiality of Northwest Butana Area, Central Sudan Elsayed Zeinelabdein1, K.A., Elsheikh2, A.E.M., Abdalla, N.H.3

Assessment of groundwater potentiality of northwest Butana Area, Central Sudan Elsayed Zeinelabdein1, K.A., Elsheikh2, A.E.M., Abdalla, N.H.3 1Faculty of Petroleum and minerals – Al Neelain University – Khartoum – Sudan 2 Faculty of Petroleum and minerals – Al Neelain University – Khartoum – Sudan, [email protected], 3Faculty of Petroleum and minerals – Al Neelain University – Khartoum – Sudan, [email protected] Abstract Butana plain is located 150 Km east of Khartoum, it is the most important area for livestock breeding in Sudan. Nevertheless, the area suffers from acute shortage in water supply, especially in dry seasons due to climatic degradation. Considerable efforts were made to solve this problem, but little success was attained. Hills, hillocks, ridges and low lands are the most conspicuous topographic features in the studied area. Geologically, it is covered by Cenozoic sediments and sandstone of Cretaceous age unconformably overlying the Precambrian basement rocks. The objective of the present study is to assess the availability of groundwater resources using remote sensing, geophysical survey and well inventory methods. Different digital image processing techniques were applied to enhance the geological and structural details of the study area, using Landsat (ETM +7) images. Geo-electrical survey was conducted using Vertical Electrical Sounding (VES) technique with Schlumberger array. Resistivity measurements were conducted along profiles perpendicular to the main fracture systems in the area. The present study confirms the existence of two groundwater aquifers. An upper aquifer composed mainly of alluvial sediments and shallow sandstone is found at depths ranging between 20- 30 m, while the lower aquifer is predominantly Cretaceous sandstone found at depths below 50 m. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 ASWAN LIBYA 1St Cataract

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 ASWAN LIBYA 1st cataract EGYPT Red Sea 2nd cataract K orosk W a d i A o R llaqi W Dal a di G oad a b g a b 3rd cataract a Kawa Kurgus H29 SUDAN H25 4th cataract 5th cataract Magashi a b Dangeil eb r - D owa D am CHAD Wadi H Meroe m a d d Hamadab lk a i q 6th M u El Musawwarat M cataract i es-Sufra d Wad a W ben Naqa A t b a KHARTOUM r a ERITREA B l u e N i le W h i t e N i le Dhang Rial ETHIOPIA CENTRAL SOUTH AFRICAN SUDAN REBUBLIC Jebel Kathangor Jebel Tukyi Maridi Jebel Kachinga JUBA Lulubo Lokabulo Ancient sites Itohom MODERN TOWNS Laboré KENYA ZAIRE 0 200km UGANDA S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 18 2014 Contents Kirwan Memorial Lecture From Halfa to Kareima: F. W. Green in Sudan 2 W. Vivian Davies Reports Animal Deposits at H29, a Kerma Ancien cemetery 20 The graffiti of Musawwarat es-Sufra: current research 93 in the Northern Dongola Reach on historic inscriptions, images and markings at Pernille Bangsgaard the Great Enclosure Cornelia Kleinitz Kerma in Napata: a new discovery of Kerma graves 26 in the Napatan region (Magashi village) Meroitic Hamadab – a century after its discovery 104 Murtada Bushara Mohamed, Gamal Gaffar Abbass Pawel Wolf, Ulrike Nowotnick and Florian Wöß Elhassan, Mohammed Fath Elrahman Ahmed Post-Meroitic Iron Production: 121 and Alrashed Mohammed Ibrahem Ahmed initial results and interpretations The Korosko Road Project Jane Humphris Recording Egyptian inscriptions in the 30 Kurgus 2012: report on the survey 130 Eastern Desert and elsewhere Isabella Welsby Sjöström W. -

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964)

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) Lake Nasser, Lower Nubia: photography by the author Degree project in Egyptology/Examensarbete i Egyptologi Carolin Johansson February 2014 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University Examinator: Dr. Sami Uljas Supervisors: Prof. Irmgard Hein & Dr. Daniel Löwenborg Author: Carolin Johansson, 2014 Svensk titel: Digital rekonstruktion av det arkeologiska landskapet i koncessionsområdet tillhörande den Samnordiska Expeditionen till Sudanska Nubien (1960–1964) English title: Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) A Magister thesis in Egyptology, Uppsala University Keywords: Nubia, Geographical Information System (GIS), Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE), digitalisation, digital elevation model. Carolin Johansson, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Box 626 SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. Abstract The Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE) was one of the substantial contributions of crucial salvage archaeology within the International Nubian Campaign which was pursued in conjunction with the building of the High Dam at Aswan in the early 1960’s. A large quantity of archaeological data was collected by the SJE in a continuous area of northernmost Sudan and published during the subsequent decades. The present study aimed at transferring the geographical aspects of that data into a digital format thus enabling spatial enquires on the archaeological information to be performed in a computerised manner within a geographical information system (GIS). The landscape of the concession area, which is now completely submerged by the water masses of Lake Nasser, was digitally reconstructed in order to approximate the physical environment which the human societies of ancient Nubia inhabited. -

Rock Art of Africa Niger

ROCK ART OF AFRICA NIGER N IGE R www.africanrockart.org www.arcadiafund.org.uk www.britishmuseum.org Mammanet 4 007.............. 92 Djaba 001....................... 1 Mammanet 5 008.............. 92 Djado 002....................... 1 Mammanet 6 009.............. 93 Djado 003....................... 2 Black Mountains 010.......... 94 Djado 004....................... 3 Last Tassili 011.................. 99 Djado 005...................... 8 Dumbell Site 012............... 103 Djado 006...................... 9 Mythical Giraffe 013........... 105 Djado 007...................... 13 Tadek Well 014.................. 108 Djado 008...................... 14 Dabous 001...................... 109 Djado 009...................... 16 Kolo 002........................... 153 Easter Aiir Mountain 001... 18 Akbar Site 003.................. 154 Ankom Monoliths 003....... 31 Rock Arch Site 004............ 157 Iwellene 001................. 32 Akore Guelta 005....... 161 Northern Air Mountains 002 67 Egatairaghe 007................ 165 Tirreghamis rain queen 003 72 Telahlaghe 008.................. 168 Grebounni 004................ 88 Dinousour......................... 171 Mammanet 2 005............. 91 Iferouane 010................... 172 Mammanet 3 006............. 91 P.O. Box 24122, Nairobi 00502, Tel: +(254) 20 3884467/3883735, Fax: +(254) 20 883674, Email: [email protected], www.africanrockart.org ISBN 9966-7055-8-9 Photos © David Coulson / TARA unless credited otherwise. Design & Layout by Richard Wachara Rock Art of Africa NIGER DJABA 001 NIGDJD0010005 -

The Emergence, Spread, and Development of the Pastoral

Andrew B. Smith. African Herders: Emergence of Pastoral Traditions. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press, 2005. 251 pp. $88.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-7591-0747-2. Reviewed by Michael Bollig Published on H-SAfrica (October, 2007) Andrew Smith has the great merit to bring to‐ olent and nonviolent intergroup relations. Gender gether archeological and ethnographic informa‐ and age in African pastoral communities are cur‐ tion on herding traditions in Africa. This is a great rently being recognized by anthropologists as key task as archeologists almost more than anthropol‐ categories for analysis. In some detail, Smith ogists stick to their excavations and their immedi‐ treats the relation between foragers and herders. ate surroundings so that a comprehensive idea on Are both lifestyles really antagonistic? Does forag‐ cultural developments does not easily arise from ing prepare for a pastoral lifestyle, or does it run their publications. Smith wants to summarize the against it? From here it is only a short distance to current state of the archeology of pastoral tradi‐ a central question that this small volume not only tions in Africa and at the end of his book gives a poses but also answers concisely: what is domesti‐ considered opinion on where research should cation and where does domestication start? move in the coming years. In chapter 2, Smith attempts to give a summa‐ Smith starts with deconstructing stereotypes ry of pastoral material culture, discussing shel‐ of African pastoralism. Leaning on an approach ters, containers, grinding equipment, and person‐ developed by Edward Said in his seminal decon‐ al attire in some detail and making use of numer‐ struction of Western notions of the Orient, Smith ous photographs.