Bad Times but Still Swinginl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Babe Ruth Scrapbooks, 1921-1935

Guide to the Lou Gehrig Scrapbooks, 1920-1942 National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhalloffame.org This guide to the scrapbooks was prepared by Howard Hamme, Intern 2007 and reviewed by Claudette Burke in December 2007. Collection Number: BA SCR 54 BL-268.56 & BL-269.56 Title: Lou Gehrig Scrapbooks Inclusive Dates: 1920-1942 Extent: 2.2 linear feet (5 scrapbooks) Repository: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract: This collection contains the scrapbooks of Henry Louis Gehrig, with materials collected by his wife Eleanor Gehrig. The scrapbooks cover the years 1920-1942, with a variety of materials documenting Gehrig’s activities on and off-field, beginning with his youth and ending with coverage of his death. Original donated scrapbooks were in two volumes. Conserved in October 2005 by NEDCC. Acquisition Information: This collection was a gift of Mrs. Eleanor Gehrig in 1956. Preferred Citation: Lou Gehrig Scrapbooks, BA SCR 54, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, National Baseball Hall of Fame. Access Restrictions: By appointment only. Available Monday - Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. A Finding aid and microfilm copy available. Copyright: Property rights reside with the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. For further information on reproduction and publication, please contact the library. Separations: None Processing Information: This collection was processed by Howard Hamme and reviewed by Claudette Burke in December 2007. History Lou Gehrig had 13 consecutive seasons with both 100 runs scored and 100 RBI, averaging 139 runs and 148 RBI. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Phone: (718) 579-4460 • E-mail: [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr & @losyankeespr World Series Champions: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2014 (2013) NEW YORK YANKEES (22-19) vs. PITTSBURGH PIRATES (17-24) Standing in AL East: ...............T1st, --- Current Streak: .................... Won 3 Sunday, May 18 • Yankee Stadium • 1:05 p.m. • Single-Admission Doubleheader Home Record: .............10-10 (46-35) Road Record:. .12-9 (44-37) Game 1: RHP Hiroki Kuroda (2-3, 4.62) vs. RHP Charlie Morton (0-5, 3.22) Day Record: ...................8-4 (32-24) Night Re >> cord: .........14-15 (53-53) Game #42 • Home Game #21 • TV: YES/MLBN • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM Pre-All-Star .................22-19 (51-44) Post-All-Star ...................0-0 (34-33) Game 2: or LHP Vidal Nuno (1-1, 6.43) vs. RHP Gerrit Cole (3-3, 3.76) vs. AL East: .................. 11-9 (37-39) vs. AL Central: ................ 0-0 (22-11) Game #43 • Home Game #22 • TV: YES • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM vs. AL West: .................. 5-6 (17-16) vs. National League: ...........6-4 (9-11) vs. RH starters: ............. 12-12 (53-54) AT A GLANCE: Today the Yankees complete a home weekend MAKING HIS MARK: 1B Mark Teixeira leads the Yankees with vs. LH starters: ............... 10-7 (32-23) series vs. Pittsburgh with a doubleheader as a result of Friday’s 9HR and is second on the team with 20RBI despite only having Yankees Score First: ..........16-4 (53-21) rainout… won Saturday’s series opener, 7-1… completed their played in 27 games thus far this season. -

Team History

PITTSBURGH PIRATES TEAM HISTORY ORGANIZATION Forbes Field, Opening Day 1909 The fortunes of the Pirates turned in 1900 when the National 2019 PIRATES 2019 THE EARLY YEARS League reduced its membership from 12 to eight teams. As part of the move, Barney Dreyfuss, owner of the defunct Louisville Now in their 132nd National League season, the Pittsburgh club, ac quired controlling interest of the Pirates. In the largest Pirates own a history filled with World Championships, player transaction in Pirates history, the Hall-of-Fame owner legendary players and some of baseball’s most dramatic games brought 14 players with him from the Louisville roster, including and moments. Hall of Famers Honus Wag ner, Fred Clarke and Rube Waddell — plus standouts Deacon Phillippe, Chief Zimmer, Claude The Pirates’ roots in Pittsburgh actually date back to April 15, Ritchey and Tommy Leach. All would play significant roles as 1876, when the Pittsburgh Alleghenys brought professional the Pirates became the league’s dominant franchise, winning baseball to the city by playing their first game at Union Park. pennants in 1901, 1902 and 1903 and a World championship in In 1877, the Alleghenys were accepted into the minor-league 1909. BASEBALL OPS BASEBALL International Association, but disbanded the following year. Wagner, dubbed ‘’The Fly ing Dutchman,’’ was the game’s premier player during the decade, winning seven batting Baseball returned to Pittsburgh for good in 1882 when the titles and leading the majors in hits (1,850) and RBI (956) Alleghenys reformed and joined the American Association, a from 1900-1909. One of the pioneers of the game, Dreyfuss is rival of the National League. -

The Chicago Cubs from 1945: History’S Automatic Out

Pace Intellectual Property, Sports & Entertainment Law Forum Volume 6 Issue 1 Spring 2016 Article 10 April 2016 The Chicago Cubs From 1945: History’s Automatic Out Harvey Gilmore Monroe College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pipself Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gilmore, The Chicago Cubs From 1945: History’s Automatic Out, 6 Pace. Intell. Prop. Sports & Ent. L.F. 225 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pipself/vol6/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Intellectual Property, Sports & Entertainment Law Forum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chicago Cubs From 1945: History’s Automatic Out Abstract Since 1945, many teams have made it to the World Series and have won. The New York Yankees, Philadelphia/Oakland Athletics, and St. Louis Cardinals have won many. The Boston Red Sox, Chicago White Sox, and San Francisco Giants endured decades-long dry spells before they finally won the orldW Series. Even expansion teams like the New York Mets, Toronto Blue Jays, Kansas City Royals, and Florida Marlins have won multiple championships. Other expansion teams like the San Diego Padres and Texas Rangers have been to the Fall Classic multiple times, although they did not win. Then we have the Chicago Cubs. The Cubs have not been to a World Series since 1945, and have not won one since 1908. -

The Collectible Significance 1

The Collectible Significance 1. One of the Earliest Known LOT 3: 1927 Signed Yankee Team Photo offered at Memory Lane Inc. Auction, December 14, 2006 3. This Piece is in Fully “Complete Signed Team Photo’s www.memorylaneinc.com Authenticated and Graded PSA in Sports”. 8 NM-MT Condition. This piece is a Rare Complete Team Incredible – not only is there a Autographed Photo from one of the complete Team autographed photo in greatest teams to ever play the Game; the existence at all! And not only has this Players, the Coaches, the Manager, the piece survived 80 years...but even more Trainer, even the Mascot are all signed on so, all of the 30 autographs on the photo this piece! It’s a true 80 year old vintage are “fully authenticated”, and in high sports rarity! It’s truly a unique piece in the grade. Each of the 30 autographs is Sports Collectable World. completely readable! Each is a dark, 2. This Piece is really a Rare clear, and fully legible signature! Overall Insider Artifact of the Game. this vintage rarity merits a grade of PSA 8 The person who got all 30 of these Near Mint to Mint – that is spectacular for people to sign the Photo was a fellow team TOP ROW ( Left to Right): Gehrig, Meusel, Ruth, Moore, Pipgras, Combs, Miller, Hoyt, Lazzeri, Koenig,Shocker, Durst, (Doc) Wood an 80 year old vintage piece. member George Pipgras – an insider! (Trainer). MIDDLE ROW: Shawkey, Girard, Grabowski, O’Leary (Coach), Huggins (Manager), Fletcher (Coach), Pennock, Wera, Collins. BOTTOM ROW: Ruether, Dugan, Paschal, Bengough, Thomas, Gazella, Morehardt, Bennett (Batboy/Mascot) Pipgras had to use his insider status and Summation: This piece has it all! It’s relationships to get everyone of his teammates to these personalities and getting them to take a moment and Unique and Rare. -

The Role of Media in the Development of Professional Baseball in New York from 1919-1929

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Crashsmith Dope: the Role of Media in the Development of Professional Baseball in New York From 1919-1929 Ryan McGregor Whittington Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Whittington, Ryan McGregor, "Crashsmith Dope: the Role of Media in the Development of Professional Baseball in New York From 1919-1929" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 308. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/308 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRASHSMITH DOPE: THE ROLE OF MEDIA IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL IN NEW YORK FROM 1919-1929 BY RYAN M. WHITTINGTON B.A., University of Mississippi, Oxford, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The University of Mississippi In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Meek School of Journalism © Copyright by Ryan M. Whittington 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT John McGraw’s New York Giants were the premier team of the Deadball Era, which stretched from 1900-1919. Led by McGraw and his ace pitcher, Christy Mathewson, the Giants epitomized the Deadball Era with their strong pitching and hard-nosed style of play. In 1919 however, The New York Times and The Sporting News chronicled a surge in the number of home runs that would continue through the 1920s until the entire sport embraced a new era of baseball. -

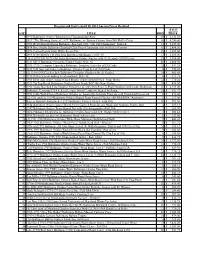

LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE 1 Actual Football Thrown from Unitas

Huggins and Scott's February 11, 2016 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Actual Football Thrown From Unitas To Berry for TD Pass in 1958 NFL Championship Game with Impeccable Provenance5 $ 62,140.00 [reserve met] 2 Historic Christy Mathewson Single-Signed Ball - From Matty's Famous 1921 Polo Grounds "Testimonial" Fundraiser19 $ [reserve 41,825.00 met] 3 1902-11 W600 Sporting Life Cabinets Honus Wagner (Uniform)—SGC 30 Good 2 37 $ 15,833.75 4 1887 N28 Allen & Ginter Hall of Fame PSA Graded Poor 1 Quartet with Anson, Clarkson, Kelly & Ward 19 $ 1,792.50 5 1888 E223 G&B Chewing Gum Con Daily SGC 10 Poor 1 19 $ 3,346.00 6 1887 N172 Old Judge SGC Graded Cards (5) 10 $ 537.75 7 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Willie Keeler (Throwing) - PSA GOOD+ 2.5 23 $ 1,075.50 8 1910 E93 Standard Caramel Ty Cobb SGC 20 Fair 1.5 17 $ 1,105.38 9 1909 E95 Philadelphia Caramel Ty Cobb SGC 10 Poor 1 32 $ 1,792.50 10 1909 E95 Philadelphia Caramel Honus Wagner--PSA Authentic 10 $ 537.75 11 1910 E98 Anonymous Ty Cobb--SGC 20 Fair 1.5 18 $ 2,509.50 12 1908 E102 Anonymous Ty Cobb--SGC 20 Fair 1.5 20 $ 2,031.50 13 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folder PSA Graded Cards (7) with PSA 4.5 Cobb 23 $ 1,314.50 14 1911 T201 Mecca Double Folders Starter Set of (27) Different with (8) SGC Graded Stars 22 $ 1,673.00 15 1911 T201 Mecca Double Folders SGC 84 NM 7 Graded Pair with None Better 11 $ 358.50 16 1911 T201 Mecca Double Folders M. -

PDF of Apr 14 Results

Huggins and Scott's April 10, 2014 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 1970 Baltimore Orioles World Series Championship Ring 29 $ 5,332.50 2 1897 “The Winning Game of 1897” Baltimore vs. Boston Cabinet from Bill Hoffer Estate 30 $ 4,740.00 3 1906 Hyatt Manufacturing Baltimore Baseball Club “Our Old Champions” Pinback 13 $ 1,659.00 4 1894 Betz Studio Baltimore Baseball Club Team Composite with (8) Hall of Famers 11 $ 2,488.50 5 1898 Cameo Pepsin Gum Willie Keeler Pin 25 $ 3,555.00 6 1895 N300 Mayo's Cut Plug Dan Brouthers (Baltimore) SGC 30 17 $ 1,185.00 7 (16) 1887-1890 N172 Old Judge Baltimore Orioles Singles with (3) Graded--All Different 25 $ 1,896.00 8 1911 M131 Baltimore Newsboy Frank Chance SGC 10 21 $ 2,488.50 9 1914 T213-2 Coupon Cigarettes Baltimore Terrapins Team Set of (9) Cards 10 $ 444.38 10 1912 C46 Imperial Tobacco Baltimore Orioles Team Set of (14) Cards 8 $ 355.50 11 (5) 1914-1915 Cracker Jack Baltimore Terrapins Singles with (2) Graded 14 $ 562.88 12 1915 D303 General Baking Fred Jacklitsch SGC 30 6 $ 177.75 13 1915 E106 American Caramel Chief Bender (Striped Hat) PSA 4--None Better 14 $ 770.25 14 1921 Tip Top Bread Baltimore Orioles Harry Frank SGC 40--None Better 10 $ 474.00 15 1952 Topps Baseball Low Number Partial Set of (243/310) Plus (7) High Numbers with Jackie Robinson 11 $ 2,133.00 16 Baltimore Terrapins 1914 Federal League Stock Certificate Signed by Rasin 10 $ 651.75 17 1921 Little World Series Baltimore Orioles vs. -

Prices Realized

Mid-Summer Classic Auction Prices Realized Lot# Title Final Price 1 EXTRAORDINARY SET OF (11) 19TH CENTURY FOLK ART CARVED AND PAINTED BASEBALL FIGURES $20,724.00 2 1903 FRANK "CAP" DILLON PCL BATTING CHAMPIONSHIP PRESENTATION BAT (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $5,662.80 1903 PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE INAUGURAL SEASON CHAMPION LOS ANGELES ANGELS CABINET PHOTO INC. DUMMY HOY, JOE 3 $1,034.40 CORBETT, POP DILLON, DOLLY GRAY, AND GAVVY CRAVATH) (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 4 1903, 1906, 1913, AND 1915 LOS ANGELES ANGELS COLORIZED TEAM CABINET PHOTOS (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,986.00 1906 CHICAGO CUBS NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS STERLING SILVER TROPHY CUP FROM THE HAMILTON CLUB OF 5 $13,800.00 CHICAGO (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 1906 POEM "TO CAPTAIN FRANK CHANCE" WITH HAND DRAWN PORTRAIT AND ARTISTIC EMBELLISHMENTS (HELMS/LA 84 6 $1,892.40 COLLECTION) 1906 WORLD SERIES GAME BALL SIGNED BY ED WALSH AND MORDECAI BROWN AND INSCRIBED "FINAL BALL SOX WIN" 7 $11,403.60 (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 8 1906 WORLD SERIES PROGRAM AT CHICAGO (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,419.60 9 1910'S GAME WORN FIELDER'S GLOVE ATTRIBUTED TO GEORGE CUTSHAW (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,562.40 C.1909 BIRD CAGE STYLE CATCHER'S MASK ATTRIBUTED TO JACK LAPP OF THE PHILADELPHIA ATHLETICS (HELMS/LA84 10 $775.20 COLLECTION) 11 C.1915 CHARLES ALBERT "CHIEF" BENDER GAME WORN FIELDER'S GLOVE (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $12,130.80 RARE 1913 NEW YORK GIANTS AND CHICAGO WHITE SOX WORLD TOUR TEAMS PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPH INCL. 12 $7,530.00 MATHEWSON, MCGRAW, CHANCE, SPEAKER, WEAVER, ET AL (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 13 RARE OVERSIZED (45 INCH) 1914 BOSTON "MIRACLE" BRAVES NL CHAMPIONS FELT PENNANT (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $3,120.00 14 1913 EBBETTS FIELD CELLULOID POCKET MIRROR (HELMS/LA 84 COLLECTION) $1,126.80 15 1916 WORLD SERIES PROGRAM AT BROOKLYN (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,138.80 1919 CINCINNATI REDS NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS DIE-CUT BANQUET PROGRAM SIGNED BY CAL MCVEY, GEORGE 16 $5,140.80 WRIGHT AND OAK TAYLOR - LAST LIVING SURVIVORS FROM 1869 CHAMPION RED STOCKINGS (HELMS/LA84.. -

Ballparks As America: the Fan Experience at Major League Baseball Parks in the Twentieth Century

BALLPARKS AS AMERICA: THE FAN EXPERIENCE AT MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PARKS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Seth S. Tannenbaum May 2019 Examining Committee Members: Bryant Simon, Advisory Chair, Department of History Petra Goedde, Department of History Rebecca Alpert, Department of Religion Steven A. Riess, External Member, Department of History, Northeastern Illinois University © Copyright 2019 by Seth S. Tannenbaum All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a history of the change in form and location of ballparks that explains why that change happened, when it did, and what this tells us about broader society, about hopes and fears, and about tastes and prejudices. It uses case studies of five important and trend-setting ballparks to understand what it meant to go to a major league game in the twentieth century. I examine the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium in the first half of the twentieth century, what I call the classic ballpark era, Dodger Stadium and the Astrodome from the 1950s through the 1980s, what I call the multi-use ballpark era, and Camden Yards in the retro-chic ballpark era—the 1990s and beyond. I treat baseball as a reflection of larger American culture that sometimes also shaped that culture. I argue that baseball games were a purportedly inclusive space that was actually exclusive and divided, but that the exclusion and division was masked by rhetoric about the game and the relative lack of explicit policies barring anyone. -

LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE 1 1905 Baltimore Orioles Cabinet

Huggins and Scott's November 12, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 1905 Baltimore Orioles Cabinet Photos Lot (8) [reserve not met] 1 $ - 2 1905 Hughie Jennings Baltimore Orioles Cabinet Photo [reserve not met] 2 $ - 3 1907-1908 Oriole Park Cabinet Photos Lot (7) 9 $ 956.00 4 Extremely Rare 1910 Photo Postcard of the 1871 Chicago White Sox Team - One of Two Known! [reserve met] 6 $ 1,314.50 5 1900s-1910s Pittsburgh Pirates Novelty Postcards (4) Including 3 Scarce Felt Mini-Pennant Examples 10 $ 717.00 6 Extremely Rare Hotel Braxton Publicity Photo Postcard of Cincinnati's Redland Field - Possibly Only 1 of 2 Known5 $[reserve 717.00 met] 7 Rare and Unique 1910 "The 'Bleachers,' Shibe Park, Philadelphia, Pa." Oversized Triple-Fold Postcard [reserve not4 met]$ - 8 1909 Pittsburgh Forbes Field Double-Fold Postcard 3 $ 203.15 9 1914 Terrapin Park, Baltimore Federal League Postcard 0 $ - 10 1930 Fairchild Aerial View Photographic Postcard with Polo Grounds Below - SGC 84 NM 7 0 $ - 11 Rare and Unusual Aerial View Real-Photo Postcard Featuring Yankee Stadium and Polo Grounds in One Shot 7 $ 1,015.75 12 Rare 1949 Washington Griffith Stadium Real Photo Postcards Trio 0 $ - 13 1950s-1980s Cincinnati Reds Team-Issued Postcards (99) Including (15) Signed Examples 8 $ 507.88 14 1870s-1910s Newspaper Baseball Illustrations (8) Including 19th Century Hall of Famers 10 $ 286.80 15 Rare 1910s "Comic Series - The Darktown Baseball Club" Glass Lantern Slides (12 Different) 13 $ 657.25 16 1916 Joe Tinker 11x14 Burke & Atwell Spring Training Photos Pair 0 $ - 17 1935 Rochester Red Wings Hanging Team Photo Display Including Walter Alston 5 $ 167.30 18 Rare 1936 Lon Warneke "Chicago American" Scorecard/Supplement 1 $ 298.75 19 1940 DiMaggio All-Stars vs.