Robert Lothman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 the Right-Wing Media Enablers of Anti-Islam Propaganda

Chapter 4 The right-wing media enablers of anti-Islam propaganda Spreading anti-Muslim hate in America depends on a well-developed right-wing media echo chamber to amplify a few marginal voices. The think tank misinforma- tion experts and grassroots and religious-right organizations profiled in this report boast a symbiotic relationship with a loosely aligned, ideologically-akin group of right-wing blogs, magazines, radio stations, newspapers, and television news shows to spread their anti-Islam messages and myths. The media outlets, in turn, give members of this network the exposure needed to amplify their message, reach larger audiences, drive fundraising numbers, and grow their membership base. Some well-established conservative media outlets are a key part of this echo cham- ber, mixing coverage of alarmist threats posed by the mere existence of Muslims in America with other news stories. Chief among the media partners are the Fox News empire,1 the influential conservative magazine National Review and its website,2 a host of right-wing radio hosts, The Washington Times newspaper and website,3 and the Christian Broadcasting Network and website.4 They tout Frank Gaffney, David Yerushalmi, Daniel Pipes, Robert Spencer, Steven Emerson, and others as experts, and invite supposedly moderate Muslim and Arabs to endorse bigoted views. In so doing, these media organizations amplify harm- ful, anti-Muslim views to wide audiences. (See box on page 86) In this chapter we profile some of the right-wing media enablers, beginning with the websites, then hate radio, then the television outlets. The websites A network of right-wing websites and blogs are frequently the primary movers of anti-Muslim messages and myths. -

Course Syllabus Summer Course

Course Syllabus Summer Course Instructor Information INSTRUCTORS DR. KIMBERLY KAGAN DR. FREDERICK KAGAN LTG (RET.) JAMES DUBIK, U.S. ARMY GUEST CO-INSTRUCTORS LTG (RET.) H.R. MCMASTER GEN (RET.) CURTIS SCAPARROTTI General Information Description: Lessons are daylong; some are divided into two blocks when they address different topics. Course Materials Required Materials Readings on Microsoft Teams Books and purchases: 1. Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2014) 2. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, eds. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984) 3. Toby Dodge, Iraq: From War to a New Authoritarianism (International Institute of Strategic Studies & Routledge: 2012) 4. Stanley A. McChrystal, My Share of the Task: A Memoir (New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2014) 5. Peter Paret, Makers of Modern Strategy: from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010) 6. Jim Scuitto, The Shadow War: Inside Russia’s and China’s Secret War to Defeat America (New York: Harper/Harper Collins, 2019) 7. Stephen Sears, Gettysburg (New York: Mariner Books Reprint, 2004) 8. John A. Warden III, The Air Campaign, Revised Edition (iUniverse: 1998) 9. Gettysburg film (https://www.amazon.com/Gettysburg-Tom-Berenger/dp/B006QPX6IG) 1 Lesson 1 July 25th TOPIC LANGUAGE & LOGIC OF WAR PURPOSE Gain foundational knowledge vital for the remainder of the course, including the levels of war framework OBJECTIVES How are militaries organized? What frameworks help us study war? How do you read a military map? 1. Learn the levels of war 2. -

Trend Analysis the Israeli Unit 8200 an OSINT-Based Study CSS

CSS CYBER DEFENSE PROJECT Trend Analysis The Israeli Unit 8200 An OSINT-based study Zürich, December 2019 Risk and Resilience Team Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study Author: Sean Cordey © 2019 Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich Contact: Center for Security Studies Haldeneggsteig 4 ETH Zurich CH-8092 Zurich Switzerland Tel.: +41-44-632 40 25 [email protected] www.css.ethz.ch Analysis prepared by: Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich ETH-CSS project management: Tim Prior, Head of the Risk and Resilience Research Group, Myriam Dunn Cavelty, Deputy Head for Research and Teaching; Andreas Wenger, Director of the CSS Disclaimer: The opinions presented in this study exclusively reflect the authors’ views. Please cite as: Cordey, S. (2019). Trend Analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study. Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich. 1 Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study . Table of Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Historical Background 5 2.1 Pre-independence intelligence units 5 2.2 Post-independence unit: former capabilities, missions, mandate and techniques 5 2.3 The Yom Kippur War and its consequences 6 3 Operational Background 8 3.1 Unit mandate, activities and capabilities 8 3.2 Attributed and alleged operations 8 3.3 International efforts and cooperation 9 4 Organizational and Cultural Background 10 4.1 Organizational structure 10 Structure and sub-units 10 Infrastructure 11 4.2 Selection and training process 12 Attractiveness and motivation 12 Screening process 12 Selection process 13 Training process 13 Service, reserve and alumni 14 4.3 Internal culture 14 5 Discussion and Analysis 16 5.1 Strengths 16 5.2 Weaknesses 17 6 Conclusion and Recommendations 18 7 Glossary 20 8 Abbreviations 20 9 Bibliography 21 2 Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study selection tests comprise a psychometric test, rigorous Executive Summary interviews, and an education/skills test. -

Army Press January 2017 Blythe

Pfc. Brandie Leon, 4th Infantry Division, holds security while on patrol in a local neighborhood to help maintain peace after recent attacks on mosques in the area, East Baghdad, Iraq, 3 March 2006. (Photo by Staff Sgt. Jason Ragucci, U.S. Army) III Corps during the Surge: A Study in Operational Art Maj. Wilson C. Blythe Jr., U.S. Army he role of Lt. Gen. Raymond Odierno’s III (MNF–I) while using tactical actions within Iraq in an Corps as Multinational Corps–Iraq (MNC–I) illustrative manner. As a result, the campaign waged by has failed to receive sufficient attention from III Corps, the operational headquarters, is overlooked Tstudies of the 2007 surge in Iraq. By far the most in this key work. comprehensive account of the 2007–2008 campaign The III Corps campaign is also neglected in other is found in Michael Gordon and Lt. Gen. Bernard prominent works on the topic. In The Gamble: General Trainor’s The Endgame: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Petraeus and the American Military Adventure in Iraq, Iraq, from George W. Bush to Barack Obama, which fo- 2006-2008, Thomas Ricks emphasizes the same levels cuses on the formulation and execution of strategy and as Gordon and Trainor. However, while Ricks plac- policy.1 It frequently moves between Washington D.C., es a greater emphasis on the role of III Corps than is U.S Central Command, and Multinational Force–Iraq found in other accounts, he fails to offer a thorough 2 13 January 2017 Army Press Online Journal 17-1 III Corps during the Surge examination of the operational campaign waged by III creating room for political progress such as the February 2 Corps. -

Counterinsurgency in the Iraq Surge

A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in US History. By Matthew T. Buchanan Director: Dr. Richard Starnes Associate Professor of History, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Committee Members: Dr. David Dorondo, History, Dr. Alexander Macaulay, History. April, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations . iii Abstract . iv Introduction . 1 Chapter One: Perceptions of the Iraq War: Early Origins of the Surge . 17 Chapter Two: Winning the Iraq Home Front: The Political Strategy of the Surge. 38 Chapter Three: A Change in Approach: The Military Strategy of the Surge . 62 Conclusion . 82 Bibliography . 94 ii ABBREVIATIONS ACU - Army Combat Uniform ALICE - All-purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment BDU - Battle Dress Uniform BFV - Bradley Fighting Vehicle CENTCOM - Central Command COIN - Counterinsurgency COP - Combat Outpost CPA – Coalition Provisional Authority CROWS- Common Remote Operated Weapon System CRS- Congressional Research Service DBDU - Desert Battle Dress Uniform HMMWV - High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle ICAF - Industrial College of the Armed Forces IED - Improvised Explosive Device ISG - Iraq Study Group JSS - Joint Security Station MNC-I - Multi-National-Corps-Iraq MNF- I - Multi-National Force – Iraq Commander MOLLE - Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment MRAP - Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (vehicle) QRF - Quick Reaction Forces RPG - Rocket Propelled Grenade SOI - Sons of Iraq UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Fund VBIED - Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device iii ABSTRACT A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. -

The Case for Larger Ground Forces Stanley Foundation

Bridging the Foreign Policy Divide The The Case for Larger Ground Forces Stanley Foundation By Frederick Kagan and Michael O’Hanlon April 2007 Frederick W. Kagan is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, specializing in defense transformation, the defense budget, and defense strategy and warfare. Previously he spent ten years as a professor of military history at the United States Military Academy (West Point). Kagan’s 2006 book, Finding the Target: The Transformation of American Military Policy (Encounter Books), exam- ines the post-Vietnam development of US armed forces, particularly in structure and fundamental approach. Kagan was coauthor of an influential January 2007 report, Choosing Victory: A Plan for Success in Iraq, advocating an increased deployment. Michael O’Hanlon is senior fellow and Sydney Stein Jr. Chair in foreign policy studies at the Brookings Institution, where he spe- cializes in U S defense strategy, the use of military force, and homeland security. O’Hanlon is coauthor most recently of Hard Power: the New Politics of National Security (Basic Books), a look at the sources of Democrats’ political vulnerability on national security in recent decades and an agenda to correct it. He previously was an analyst with the Congressional Budget Office. Brookings’ Iraq Index project, which he leads, is a regular feature on The New York Times Op-Ed page. e live at a time when wars not only rage national inspections. What will happen if the in nearly every region but threaten to US—or Israeli—government becomes convinced Werupt in many places where the current that Tehran is on the verge of fielding a nuclear relative calm is tenuous. -

Working Relationship

U.S. hit IS with largest non-nuclear bomb — Page 2 @The_Derrick The Derrick and The News-Herald TheDerrick.com TheDerrickNews OCDerrick © OIL CITY, PA. FRIDAY, APRIL 14, 2017 (800) 352-1002 (814) 676-7444 $1.00 Dan Rooney dies Saving mall a priority Economic development committee to work on issue By SALLY BELL His comments came at a Thursday ident, suggested that local business Others, including Bonnie Summers, Staff writer meeting of the Cranberry supervisors. owners form a conglomerate and buy a member of the township’s compre- Also in attendance were Supervisors the mall from the owner. hensive plan steering committee, and The future of Cranberry Town- Harold Best and Jerry Brosius, along The mall is private property and its Stephanie Felmlee, a local business ship’s mall will likely be one of the with township Manager Chad Findlay. owner lives in California. On the Ve- owner, said that communication must focal points of an economic develop- The mall came up as a point of nango County parcel viewer, the own- be opened between the township and ment committee that is being formed. discussion during the public comment er is listed as SSR LLC. the mall’s owner in California to dis- “We can’t lose that mall,” said Fred portion of the meeting. The township has never owned the cuss the property’s future. Buckholtz, supervisors chair. Marilyn Brandon, a Cranberry res- mall, Best said. See CRANBERRY, Page 8 ‘They have the opportunity to refocus their lives and have another chance’ Dan Rooney, the powerful and popular Oil City Steelers chairman whose name is attached to the NFL’s landmark initiative in minority hiring, dies at 84. -

Counterterrorism Within the Afghanistan Counterinsurgency

i [H.A.S.C. No. 111–102] COUNTERTERRORISM WITHIN THE AFGHANISTAN COUNTERINSURGENCY HEARING BEFORE THE TERRORISM, UNCONVENTIONAL THREATS AND CAPABILITIES SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD OCTOBER 22, 2009 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57–054 WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 TERRORISM, UNCONVENTIONAL THREATS AND CAPABILITIES SUBCOMMITTEE ADAM SMITH, Washington, Chairman MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina JEFF MILLER, Florida ROBERT ANDREWS, New Jersey FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island JOHN KLINE, Minnesota JIM COOPER, Tennessee BILL SHUSTER, Pennsylvania JIM MARSHALL, Georgia K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, Texas BRAD ELLSWORTH, Indiana THOMAS J. ROONEY, Florida PATRICK J. MURPHY, Pennsylvania MAC THORNBERRY, Texas BOBBY BRIGHT, Alabama SCOTT MURPHY, New York TIM MCCLEES, Professional Staff Member ALEX KUGAJEVSKY, Professional Staff Member ANDREW TABLER, Staff Assistant (II) C O N T E N T S CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF HEARINGS 2009 Page HEARING: Thursday, October 22, 2009, Counterterrorism within the Afghanistan Coun- terinsurgency ........................................................................................................ 1 APPENDIX: Thursday, October 22, 2009 ................................................................................... -

Rebuilding Iraqi Television: a Personal Account

Rebuilding Iraqi Television: A Personal Account By Gordon Robison Senior Fellow USC Annenberg School of Communication October, 2004 A Project of the USC Center on Public Diplomacy Middle East Media Project USC Center on Public Diplomacy 3502 Watt Way, Suite 103 Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281 www.uscpublicdiplomacy.org USC Center on Public Diplomacy – Middle East Media Project Rebuilding Iraqi Television: A Personal Account By Gordon Robison Senior Fellow, USC Annenberg School of Communication October 27, 2003 was the first day of Ramadan. It was also my first day at a new job as a contractor with the Coalition Provisional Authority, the American-led administration in Occupied Iraq. I had been hired to oversee the news department at Iraqi television. I had been at the station barely an hour when news of a major attack broke: at 8:30am a car bomb had leveled the Red Cross headquarters. The blast was enormous, and was heard across half the city. When the pictures began to come in soon afterwards they were horrific. The death toll began to mount. Then came word of more explosions: car bombs destroying three Iraqi police stations. A fourth police station was targeted but the bomber was intercepted in route. At times like this the atmosphere in the newsroom at CNN, the BBC or even a local television station is focused, if somewhat chaotic. Most news operations have a plan for dealing with big, breaking stories. Things in the newsroom move quickly, and they can get very stressful, but things do happen. Also, this was hardly the first time an atrocity like this had taken place. -

I. Tv Stations

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) MB Docket No. 17- WSBS Licensing, Inc. ) ) ) CSR No. For Modification of the Television Market ) For WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida ) Facility ID No. 72053 To: Office of the Secretary Attn.: Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF WSBS LICENSING, INC. SPANISH BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. Nancy A. Ory Paul A. Cicelski Laura M. Berman Lerman Senter PLLC 2001 L Street NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (202) 429-8970 April 19, 2017 Their Attorneys -ii- SUMMARY In this Petition, WSBS Licensing, Inc. and its parent company Spanish Broadcasting System, Inc. (“SBS”) seek modification of the television market of WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida (the “Station”), to reinstate 41 communities (the “Communities”) located in the Miami- Ft. Lauderdale Designated Market Area (the “Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA” or the “DMA”) that were previously deleted from the Station’s television market by virtue of a series of market modification decisions released in 1996 and 1997. SBS seeks recognition that the Communities located in Miami-Dade and Broward Counties form an integral part of WSBS-TV’s natural market. The elimination of the Communities prior to SBS’s ownership of the Station cannot diminish WSBS-TV’s longstanding service to the Communities, to which WSBS-TV provides significant locally-produced news and public affairs programming targeted to residents of the Communities, and where the Station has developed many substantial advertising relationships with local businesses throughout the Communities within the Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA. Cable operators have obviously long recognized that a clear nexus exists between the Communities and WSBS-TV’s programming because they have been voluntarily carrying WSBS-TV continuously for at least a decade and continue to carry the Station today. -

Barnes Conversations Transcript

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Fred Barnes, The Weekly Standard Table of Contents I: Covering Ford, Carter, and Reagan 00:15 – 20:40 II: The Reagan Years 20:40 – 42:22 III: Politics in the Nineties 42:22 – 1:01:37 IV: Talking Politics on Television 1:01:37 – 1:24:44 I: Covering Ford, Carter, and Reagan (00:15 – 20:40) KRISTOL: Welcome back to CONVERSATIONS. I’m Bill Kristol, and I’m very pleased to be joined today by my friend and colleague, Fred Barnes. Fred, thanks for taking the time to do this. BARNES: Well, glad to be here. KRISTOL: So I came to Washington in 1985 but I had already read you for a decade before then covering the White House. How did that happen? BARNES: Well, I was covering the White House for The New Republic magazine, which everyone knows now was a very, very liberal magazine. It wasn’t that liberal then. The owner was Marty Peretz, who was sort of, he’d come sort of halfway down the neoconservative trail, and Charles Krauthammer, of course, was the big foreign policy writer there. And so it was very congenial. The New Republic had a column for a long time called “White House Watch,” and it was very good. It was written for years by a man named John Osborne, then he was replaced by Mort Kondracke, my friend, and, of course, you know, who was in 1985 was hired to be the bureau chief for Newsweek. So he left. And I had gotten to know a little bit Mike Kinsley, who was then the editor of The New Republic, and they hired me to come in and really write this “White House Watch” column, which I did, almost every week. -

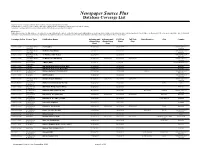

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List "Cover-to-Cover" coverage refers to sources where content is provided in its entirety "All Staff Articles" refers to sources where only articles written by the newspaper’s staff are provided in their entirety "Selective" coverage refers to sources where certain staff articles are selected for inclusion Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverage Policy Source Type Publication Name Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text State/Province City Country Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Start Stop Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 20/20 (ABC) 01/01/2006 01/01/2006 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 48 Hours (CBS News) 12/01/2000 12/01/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes (CBS News) 11/26/2000 11/26/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes II (CBS News) 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover International 7 Days (UAE) 11/15/2010 11/15/2010 United Arab Emirates Newspaper Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian National News Wire 09/13/2003 09/13/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian Sports News Wire 10/25/2000 10/25/2000 Australia All Staff Articles U.S.