Understanding Representations of Ethos and Self in Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEFINING FORM / a GROUP SHOW of SCULPTURE Curated by Indira Cesarine

DEFINING FORM / A GROUP SHOW OF SCULPTURE Curated by Indira Cesarine EXHIBITING ARTISTS Alexandra Rubinstein, Andres Bardales, Ann Lewis, Arlene Rush, Barb Smith, Christina Massey, Colin Radcliffe, Daria Zhest, Desire Rebecca Moheb Zandi, Dévi Loftus, Elektra KB, Elizabeth Riley, Emily Elliott, Gracelee Lawrence, Hazy Mae, Indira Cesarine, Jackie Branson, Jamia Weir, Jasmine Murrell, Jen Dwyer, Jennifer Garcia, Jess De Wahls, Jocelyn Braxton Armstrong, Jonathan Rosen, Kuo-Chen (Kacy) Jung, Kate Hush, Kelsey Bennett, Laura Murray, Leah Gonzales, Lola Ogbara, Maia Radanovic, Manju Shandler, Marina Kuchinski, Meegan Barnes, Michael Wolf, Nicole Nadeau, Olga Rudenko, Rachel Marks, Rebecca Goyette, Ron Geibel, Ronald Gonzalez, Roxi Marsen, Sandra Erbacher, Sarah Hall, Sarah Maple, Seunghwui Koo, Shamona Stokes, Sophia Wallace, Stephanie Hanes, Storm Ascher, Suzanne Wright, Tatyana Murray, Touba Alipour, We-Are-Familia x Baang, Whitney Vangrin, Zac Hacmon STATEMENT FROM CURATOR, INDIRA CESARINE “What is sculpture today? I invited artists of all genders and generations to present their most innovative 2 and 3-dimensional sculptures for consideration for DEFINING FORM. After reviewing more than 600 artworks, I selected sculptures by over 50 artists that reflect new tendencies in the art form. DEFINING FORM artists defy stereotypes with inventive works that tackle contemporary culture. Traditionally highly male dominated, I was inspired by the new wave of female sculptors making their mark with works engaging feminist narratives. The artworks in DEFINING FORM explode with new ideas, vibrant colors, and display a thoroughly modern sensibility through fearless explorations of the artists and unique usage of innovative materials ranging from fabric, plastic, and foam to re-purposed and found objects including chewing gum, trash and dirt. -

Bangor University to Cut £5M

Bangor Remembrance 2018 100 Years On - Bangor Remembers The Fallen FREE Page AU Match 9 Reports Inside AU Focus Fixture: Ultimate Frisbee Page 53 November Issue 2018 Issue No. 273 seren.bangor.ac.uk @SerenBangor Y Bangor University Students’ Union English Language Newspaper Bangor University To Cut £5m VICE-CHANCELLOR EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW “Protect the student experience at all costs,” says Vice-Chancellor John G. Hughes FULL by FINNIAN SHARDLOW also mentioned as a reason for these However, Hughes says further cuts unions. Plaid Cymru’s Sian Gwenllian cuts. will need to be made to secure Bangor’s AM expressed “huge concern,” INTERVIEW angor University are aiming to 50 jobs are at risk as compulsory long-term future. maintaining that the university must make savings of £5m. redundancies are not ruled out. “What we’re doing is taking prudent avoid compulsory redundancies. Sta received a letter from Vice- In the letter, seen by Newyddion steps to make sure we don’t get into a In an exclusive interview with Seren, INSIDE BChancellor, John G. Hughes, warning 9, Prof. Hughes said: “Voluntary serious situation.” Hughes said that students should of impending “ nancial challenges” redundancy terms will be considered Hughes added: “ ere was a headline not feel the e ects of cuts, and that facing the institution. in speci c areas, but unfortunately, in e Times about three English instructions have been given to “protect PAGE 4-5 e letter cites the demographic the need for compulsory redundancies universities being close to bankruptcy. the student experience at all costs,” decline in 18-20 year-olds which has cannot be ruled out at this stage.” An important point is that Bangor is especially in “student facing areas.” impacted tuition fee revenues as a is letter comes 18 months a er nowhere near that. -

Visual Arts in the Urban Environment in the German Democratic Republic: Formal, Theoretical and Functional Change, 1949–1980

Visual arts in the urban environment in the German Democratic Republic: formal, theoretical and functional change, 1949–1980 Jessica Jenkins Submitted: January 2014 This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in partial fulfilment of its requirements) at the Royal College of Art Copyright Statement This text represents the submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Royal College of Art. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research for private study, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. Author’s Declaration 1. During the period of registered study in which this thesis was prepared the author has not been registered for any other academic award or qualification. 2. The material included in this thesis has not been submitted wholly or in part for any academic award or qualification other than that for which it is now submitted. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the very many people and institutions who have supported me in this research. Firstly, thanks are due to my supervisors, Professor David Crowley and Professor Jeremy Aynsley at the Royal College of Art, for their expert guidance, moral support, and inspiration as incredibly knowledgeable and imaginative design historians. Without a generous AHRC doctoral award and an RCA bursary I would not have been been able to contemplate a project of this scope. Similarly, awards from the German History Society, the Design History Society, the German Historical Institute in Washington and the German Academic Exchange Service in London, as well as additional small bursaries from the AHRC have enabled me to extend my research both in time and geography. -

The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 12-15-2020 The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Gideon Reuveni University of Sussex Diana University Franklin University of Sussex Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reuveni, Gideon, and Diana Franklin, The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism. (2021). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Edited by IDEON EUVENI AND G R DIANA FRANKLIN PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS | WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-711-9 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of librar- ies working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61249-703-7. Cover artwork: Painting by Arnold Daghani from What a Nice World, vol. 1, 185. The work is held in the University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep, Arnold Daghani Collection, SxMs113/2/90. -

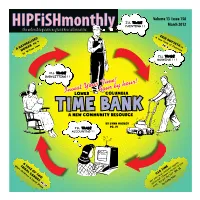

Hour by Hour!

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

Vortrag Eckhart Gillen Über Lea Grundig

Jüdische Identität und kommunistischer Glaube Lea Grundigs Weg von Dresden über Palästina zurück nach Dresden, Bezirkshauptstadt der DDR 1922-1977 Für Maria Heiner und Esther Zimmering Karoline Müller, die als erste westdeutsche Galeristin mitten im Kalten Krieg 1964 und 1969 Lea Grundig in ihrer Westberliner „Ladengalerie“ ausgestellt hat, schreibt in ihren „Erinnerungen an Lea Grundig“: „Lea Grundig, die von wenigen sehr geliebt wurde, wird auch über ihren Tod hinaus gehasst. Sie war sehr skeptisch, wenn ein Andersdenkender zu ihr freundlich war. Bei einem Lob aus dem anderen Gesellschaftssystem müsse sie ihr Werk überdenken: ‚Was ich mache, ist Gebrauchskunst. Ob es Kunst im akademischen Sinne ist, interessiert mich nicht. Ich bin eine Agitatorin.“1 In der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung wurde sie 1969 in einer Kritik ihrer Ausstellung in der Ladengalerie „Chef-Propagandistin“ der DDR tituliert. 2 Unter den Funktionären der SED galt sie als herrisch, kompliziert und empfindlich als eine, die sich störrisch gegen die geschmeidige Anpassung der Parteilinie an die Routine des „realen Sozialismus“ in den Farben der DDR gewehrt hat. Reformer und Dissidenten in der DDR hielten sie für eine Stalinistin. Beide Seiten sahen in ihr eine gläubige Kommunistin, die im Grunde unpolitisch und naiv gewesen sei. Nach dem überraschenden Wechsel von Walter Ulbricht zu dem angeblichen Reformer Erich Honecker beklagte sie, dass plötzlich alle Porträts des Staatsratsvorsitzenden aus der Öffentlichkeit verschwunden seien und Ulbricht, trotz seiner Verdienste um die DDR von heute auf morgen der „damnatio memoriae“ verfallen sei.3 In der Frankfurter Rundschau erklärte sie 1973 wenige Jahre vor ihrem Tod 1977 anlässlich der Ausstellung aller Radierungen und des Werkverzeichnisses in der Ladengalerie: „Ich sage ja zur Gesamtentwicklung, zum Grundprinzip absolut und mit meiner ganzen Kraft ja.“4 Selbst den westdeutschen Feministinnen war sie zu dogmatisch und politisch. -

Hans Grundig's Masterful

Martin Schmidt An Iconic Work of New Objectivity: Hans Grundig’s Masterful “Schüler mit roter Mütze” The artistic ethos of the painter Hans Grundig is reflected in his attempt to conjoin the sometimes one-dimensional worldview of politically informed art with a more universal human outlook. This is to say that in addition to his overriding preoccupation with the social conditions that prevailed during his turbulent times – particularly class conflicts –, he was nonetheless able to paint with a deeply felt lyricism. Without this aspect, his art would probably have come across as passionless and merely declamatory. And so we always find the human being as the key point of reference for his care and concern, not just ab- stract principles. A highly idiosyncratic way of looking at things shines through Grundig’s work, one that mixes naiveté with artifice, pro- clamation with lyricism, and that supercharges non-descript details with a deeply felt, magical poetry. Lea, the school friend who later became his wife and life’s companion, and whom he fondly referred to as his “silver one” in his memoirs, described him as “a dreamer and warrior rolled into one.” He wanted his art Karl Hubbuch. The schoolroom. 1925. Oil/cardboard and wood. Private Col- to have a social impact, of course. Yet he was also well aware that lection choosing the right side in class warfare, as demanded by the Ger- man Communist Party (KPD) and later by its East German succes- seems designed for titanic hands, assuming spatial logic is applied. Grundig evi- sor (SED), was an artistic dead end that usually produced less than dently is unconcerned about the plausibility of his center-line perspective. -

Download As Pdf

Journal of Historical Fictions 1:1 2017 Natasha Alden – Jacobus Bracker – Joanne Heath – Julia Lajta-Novak – Nina Lubbren – Kate Macdonald The Journal of Historical Fictions 1:1 2017 Editor: Dr Kate Macdonald, University of Reading, UK Department of English Literature University of Reading Whiteknights Reading RG6 6UR United Kingdom Co-Editors: Dr Natasha Alden, Aberystwyth University; Jacobus Bracker, University of Hamburg; Dr Joanne Heath; Dr Julia Lajta-Novak, University of Vienna; Dr Nina Lubbren, Anglia Ruskin University Advisory Board Dr Jerome de Groot, University of Manchester Nicola Griffith Dr Gregory Hampton, Howard University Professor Fiona Price, University of Chichester Professor Martina Seifert, University of Hamburg Professor Diana Wallace, University of South Wales ISSN 2514-2089 The journal is online available in Open Access at historicalfictionsjournal.org © Creative Commons License: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Reading 2017 Contents Victims, heroes, perpetrators: German art reception and its re-construction of National Socialist persecution Johanna Huthmacher 1 Curating the past: Margins and materiality in Sydney Owenson, Lady Morgan’s The Wild Irish Girl Ruth Knezevich 25 Contentious history in “Egyptian” television: The case of Malek Farouq Tarik Ahmed Elseewi 45 The faces of history. The imagined portraits of the Merovingian kings at the Versailles museum (1837-1842) Margot Renard 65 Masculine crusaders, effeminate Greeks, and the female historian: Relations of power in Sir Walter Scott’s Count Robert of Paris Ioulia Kolovou 89 iii Victims, heroes, perpetrators: German art reception and its re-construction of National Socialist persecution Johanna Huthmacher, Panorama Museum Bad Frankenhausen, Germany Abstract: Shortly after World War II, the German artists Horst Strempel and Hans Grundig created works that depicted National Socialist persecution. -

The Military History Museum in Dresden: Between Forum and Temple Author(S): Cristian Cercel Source: History and Memory, Vol. 30, No

The Military History Museum in Dresden: Between Forum and Temple Author(s): Cristian Cercel Source: History and Memory, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Spring/Summer 2018), pp. 3-39 Published by: Indiana University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/histmemo.30.1.02 Accessed: 19-06-2018 08:16 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History and Memory This content downloaded from 78.48.172.3 on Tue, 19 Jun 2018 08:16:18 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Military History Museum in Dresden Between Forum and Temple CRISTIAN CERCEL This article analyzes the Military History Museum (MHM) in Dresden against the backdrop of recent theoretical elaborations on agonistic memory, as opposed to the cosmopolitan and antagonistic modes of remembering. It argues that the MHM attempts to combine two functions of the museum: the museum as forum and the museum as temple. By examining the concept underpinning the reor- ganization of the permanent exhibition of the MHM, and by bringing examples from both the permanent and temporary exhibitions, the article shows that the discourse of the MHM presents some relevant compatibilities with the principles of agonistic memory, yet does not embrace agonism to the full. -

Bucerius Newsletter Winter 2014

Fall 2014 On September 18 the Bucerius Institute Together with the Haifa Center for German organized together with the Rosa Luxemburg and European Studies (HCGES) the Foundation and the Gottlieb Schumacher Bucerius Institute will open the academic Institute a symposium about the artist Lea year 2014/15 on October 30, presenting Grundig . Dr. Eckhard Gillen from Berlin, Oliver the play: “The Inheritents of the Silence” . Sukrow from Heidelberg and Dr. Thomas Flierl The play depicts a meeting between Esther, from Berlin introduced Lea Grundig as an artist, the daughter of Holocaust survivors and discussed her work and also spoke about her Eva, the granddaughter of a Nazi officer. identity as a German, a communist and a Jew. After struggling with their own past they are The exhibition: Lea Grundig in Dresden and able to find a common language and Palestine 1933-1948, is shown in the Igal together to overcome the silence of the Pressler Museum, Wolfson Street 54, in Tel Aviv second generation together. The play will and at the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt a.M. take place at 18:00 at the Edmond Safdie- Auditorium, Mulit-Purpose-Building. During the summer break, Dr. Amos Morris - From June 16-18, the International Reich , Director of the Bucerius Center, went to Consortium of Research on Antisemitism Europe to extend the centers research frame. As and Racism (ICRA) held the international part of the international research group:”History conference: “Narratives of Violence” at the of Race and Eugenics” he participated in a Central European University of Budapest. conference in Cork in Irland. -

Renée Stout Born 1958, Junction City, Kansas Root Chart # 1, 2006 Graphite on Tracing Vellum Museum Purchase: Letha Churchill Walker Fund, 2008.0329

+ + Israhel van Meckenem the younger (1440 or 1445–1503) born Meckenheim, Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany); died Bocholt, Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany) after Master of the Housebook (circa 1470–1500) The Lovers, late 1400s engraving Gift of the Max Kade Foundation, 1969.0122 In the 15th century, gardens often inspired connotations of courtly love in chivalric medieval romances, poetry, and art. Sometimes referred to as gardens of love or pleasure gardens, these relatively private spaces offered respite from the very public arenas of court. Courtiers would use these gardens to sit, read, play games, roam the walkways, and have discreet meetings. Plants often contributed to the architecture of courtly gardens. Here, the suggestion of a grove sets the tone for the intimate activities of the couple. The smells of flowers and herbs, the colors of blooms and leaves, the sounds of birds, and of the running water of fountains all added to the sensuality of medieval pleasure gardens. + + + + Esaias van Hulsen (circa 1585–1624) born Middelburg, Dutch Republic (present-day Netherlands); died Stuttgart, Duchy of Württemberg (present-day Germany) Console of scrolling foliate forms with flowers and two birds, and a hunter shooting rabbits, circa 1610s engraving Museum purchase: Letha Churchill Walker Memorial Art Fund, 2013.0204 In this engraving van Hulsen carries on the longstanding ornament print tradition of imagining complex, elegant botanical structures. Ornament prints encourage viewers to search through the depicted foliage for partially hidden figures and forms. In this artwork viewers can find insects and birds. Van Hulsen adds a relatively orthodox landscape populated by a rabbit hunter, his dog, and their quarry to this fantastic realm of plants and animals.