Best Practice Recommendations for Publishing a Student Anthology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View Project

Start page displays most visited websites Interface streamlined to only most needed Reading view extracts text content and and new items from user’s favorite websites functions. displays it into a readable format 11:55 PM 11:55 PM 11:55Notices PM 11:55 PM Search or Type URL… Conventional W… Read Conventional W… Back Most Visited The New York Times AARP Youtube Medicare.gov Recent Updates Bob Dylan’s Secret Archive www.nytimes.com Foods to Avoid Before Bed www.aarp.org How to Make Applesauce www.youtube.com Back Tabs More Less frequent settings tucked away Simple and quick acess to tabs 11:55Notices PM 11:55 PM 11:55Notices PM 11:55 PM The New York Times Read The New York Times Read Tabs Ta b Back Back The New York Times Forward Refresh History www.nytimes.com Share this page AARP - Bringing Real… Bookmark this page www.aarp.org Add to homescreen Medicare.gov www.medicare.gov Advanced Settings Back Tabs Close Back Close More Combines modern functionality with Complete removal of scientific functions. Operators changes color on tap. traditional layout. 11:55 PM 11:55 PM 11:55 PM 1,234 1,517.5 1,234 567 / 2 + 1,234 567 / 2 + 1,234 = 1517.5 567 / 2 + 1,234 ce + - % ans ce + - % ans ce + - % ans 7 8 9 / 7 8 9 / 7 8 9 / 4 5 6 x 4 5 6 x 4 5 6 x 1 2 3 - 1 2 3 - 1 2 3 - 0 . = + 0 . = + 0 . = + Operators changes color on tap. Maintain similar color scheme to the Braun ET 66 Calculator. -

KLOS BWTB Jan. 19Th 2014

1 PLAYLIST JANUARY 19TH 2014 BROADCAST LIVE FROM THE KOBE STEAKHOUSE SEAL BEACH, CA 1 2 9AM The Beatles - Magical Mystery Tour - Magical Mystery Tour (EP) (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocals: Paul and John When Paul McCartney was in the U.S. in early April 1967 he came up with the idea for a Beatles television film about a mystery tour on a bus. During the April 11 flight back home he began writing lyrics for the title song and sketching out some ideas for the film. Upon his arrival in London, Paul pitched his idea to Brian Epstein who happily approved. Paul then met with John to go over the details and the two began work on the film’s title track. The title track was written primarily by Paul but was not finished when McCartney brought the song in to be recorded on April 25, 1967. John helped with 2 3 the missing pieces during the session. The Beatles - The Fool On The Hill - Magical Mystery Tour (EP) (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: Paul Sitting alone at the piano, Paul McCartney recorded a mono two-track demo of “The Fool On the Hill” on September 6, 1967. A more proper recording would take place September 25. On the 25th three takes of the basic rhythm track were recorded, including harmonicas played by John and George. Paul first brought the song to John’s attention in mid-March while the two were working on the lyrics for “With A Little Help From My Friends.” John said to write down the lyrics so he wouldn’t forget them. -

Ingesting Text

Ingesting text This is from Section 15.3 of the Modern Data Science with R book. Using rvest Take a look at the Wikipedia List of songs recorded by the Beatles. In the book the second list of Other songs is used. I have used the Main Songs list. A great reference for regex (commands like gsub) is the r4ds book, see Chapter 14 about strings library(rvest) ## Loading required package: xml2 library(tidyr) library(methods) library(mdsr) ## Loading required package: dplyr ## ## Attaching package: 'dplyr' ## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats': ## ## filter, lag ## The following objects are masked from 'package:base': ## ## intersect, setdiff, setequal, union ## Loading required package: lattice ## Loading required package: ggformula ## Loading required package: ggplot2 ## Loading required package: ggstance ## ## Attaching package: 'ggstance' ## The following objects are masked from 'package:ggplot2': ## ## geom_errorbarh, GeomErrorbarh ## ## New to ggformula? Try the tutorials: ## learnr::run_tutorial("introduction", package = "ggformula") ## learnr::run_tutorial("refining", package = "ggformula") ## Loading required package: mosaicData ## Loading required package: Matrix ## ## Attaching package: 'Matrix' 1 ## The following object is masked from 'package:tidyr': ## ## expand ## ## The 'mosaic' package masks several functions from core packages in order to add ## additional features. The original behavior of these functions should not be affected by this. ## ## Note: If you use the Matrix package, be sure to load it BEFORE -

Hallo M.B.M., Hallo BEATLES-Fan! Die Originalen ANTHOLOGY-Cds

Angebot gilt meistens längere Zeit aber nicht auf Dauer. Die InfoMails archivieren wir auf Dauer auf unserer Internetseite. Dienstag, 7. Januar 2014 Hallo M.B.M., hallo BEATLES-Fan! Die originalen ANTHOLOGY-CDs November 1995: THE BEATLES: Stereo-Doppel-CD ANTHOLOGY 1. EMI Apple 7243 8 34445 2 6, Europa. 29,90 € Free As A Bird; We were four guys ... that’s all; That’ll Be The Day; In Spite Of All The Danger; Sometimes I’d borrow ... those still exist; Hallelujah I Love Her So; You’re Be Mine; Cayenne; First of all ... it didn’t do a thing here; My Bonnie; Ain’t She Sweet; Cry For A Shadow; Brian was A Beautiful Guy ... He Presented Us Well; I secured them ... a Beatle drink even then; Searchin’; Three Cool Cats; Sheik Of Araby; Like Dreamers Do; Hello Little Girl; Well the recording test ... by my Artists; Besame Mucho; Love Me Do; How Do You Do It?; Please Please Me; The One After 909; The One After 909; Lend Me Your Comb; I’ll Get You; We were performers ... in Britain; I Saw Her Standing There; From Me To You; Money (That’s What I Want); You Really Got A Hold On Me; Roll Over Beethoven; She Loves You; Till There Was You; For our last number ..; Twist And Shout; This Boy; I Want To Hold Your Hand; Boys what I was thinking ...; Moonlight Bay; Can’t Buy Me Love; All My Loving; You Can’t Do That; And I Love Her; A Hard Day’s Night; I Wanna Be Your Man; Long Tall Sally; Boys; Shout; theme music; I’ll Be Back; I’ll Be Back; You Know What To Do; No Reply; Mister Moonlight; Leave My Kitten Alone; No Reply; Eight Days A Week; Eight Days A Week; Kansas City - Hey Hey Hey Hey. -

George Harrison Birthday Special 2016

1 George Harrison Birthday Special 2016 2 George Harrison – Crackerbox Palace - Thirty-Three & 1/3 ‘76 This was the most successful track off the LP, and the title originally considered for the album. It’s content was inspired by the comedian Lord Buckley, a longtime favorite of George’s. Another Eric Idle directed promo film, featuring the future Mrs. Olivia Harrison, future Rutle Neil Innes, and the numerous children of Derek Taylor. The Beatles - You Like Me Too Much - Help! (Harrison) Lead vocal: George Recorded in eight takes on February 15, 1965. The introduction features Paul and George Martin on a Steinway piano and John playing an electric piano. On U.S. album: Beatles VI - Capitol LP The Beatles - Do You Want To Know A Secret – Please Please Me (McCartney-Lennon) Lead vocal: George Recorded February 11, 1963. Written primarily by John Lennon for George Harrison to sing. The song was given to another Brian Epstein-managed act, Billy J. Kramer with the Dakotas, to cover. Their version topped the British charts in late spring 1963. Inspired by "I'm Wishing," a song from Walt Disney’s 1937 animated film “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” that Lennon’s mother used to sing to him when he was a child. On U.S. albums: Introducing… The Beatles - Vee-Jay LP The Early Beatles - Capitol LP 3 BREAK… The Beatles - Don’t Bother Me – With The Beatles (Harrison) Lead vocal: George George Harrison’s first recorded original song. While some may see it as a misfortune that Harrison was surrounded by two of the most gifted songwriters in history, this proximity gave him great insight into the mechanics of writing a song from scratch. -

Libertarian Anthology 3

Anarchism, Trade Unionism, Councilism and Revolutionary Syndicalism. This publication is not subject to any copyright. We will only ask you to acknowledge its source should you wish to use any of its contents. Libertarian Anthology III Edited, Published and Produced by: Acracia with the co-operation of Grupo Cultural de Estudios Sociales de Melbourne November 2012 Contents Introduction 5 The basis of Trade Unionism 8 by Emile Pouget The origins of anarcho-syndicalism 27 by Rufolf Rocker Fernand Pelloutier and the dilemma of revolutionary syndicalism 30 by Alan Spitzer Councilism and Syndicalism: a historical perspective 38 by Andrew Giles-Peters Anarchism and Trade Unionism 43 by Gaston Gerard his third issue of Libertarian Anthology is devoted to the topic of trade unionism and the evolvement by one of the groupings within it to Trevolutionary ideals; whom ever has taken the patience to study both the economic and political development of society over the past two centuries will come to realise that the goals of anarcho-syndicalism did not evolve from unachievable utopic concepts conveyed by a few lunatic innovative goodhearted individuals, instead, these goals are the outcome of constant struggles within the maladjusted social conditions. As a result we have the pleasure in presenting the reader with a collection of articles which we hope will demystify the misunder- standing of anarcho-syndicalism. There has always existed at every cross point within any defined period in history the continuous dilemma for anarchists whether to belong to a trade organisation or not. This dilemma can be traced back to the perpetual conflict within the anarchist ideology between the individualist and the collectivist and therefore it must be recognised that anarcho-syndicalism is not an accepted method of action by all anarchists. -

LSUG March 24Th II 2013

Playlist March 24th 2013 The Beatles…The Songs They Gave Away Hour #1 “One And One Is Two” – The Strangers w/Mike Shannon: Released as a Phillips single on May 8, 1964 in the U.K. only. The Beatles demo of this song from January 1964 was recorded live in a hotel room in Paris. It has surfaCed on some bootlegs and can also be heard in a BROW that was posted baCk in 2008. “From A Window” – Billy J. Kramer & The Dakotas: Released on a Parlophone single on July 17, 1964 in the U.K. and an Imperial single in the U.S. on August 12, 1964. The song was produCed by George Martin. John Lennon and Paul MCCartney attended the session on May 29, 1964 and although no Beatle-performed demos of this traCk have surfaCed, Paul MCCartney Can be heard singing the high G note at the end of the song himself (“…niiiight”) right on the record because Billy J. Kramer had trouble hitting the note. Nobody I Know” – Peter and Gordon: Released as a U.K. Parlophone single on May 29, 1964 and on Capitol in the U.S. on June 15, 1964. ReCorded by Peter and Gordon on January 21, 1964. The Beatles never reCorded this song. Paul likely just demoed it live and Peter and Gordon took it from there. “Like Dreamers Do” – The Applejacks: Released as a DeCCa U.K. single on June 5, 1964 and in the U.S. on the London label on June 6 ,1964. The most well-known Beatles demo of this was reCorded at their unsuCCessful New Year’s Day 1962 DeCCa audition. -

Pdf/Beatles Chronology Timeline

INDEX 1-CHRONOLOGY TIMELINE - 1926 to 2016. 2-THE BEATLES DISCOGRAPHY. P-66 3-SINGLES. P-68 4-MUSIC VIDEOS & FILMS P-71 5-ALBUMS, (Only Their First Release Dates). P-72 6-ALL BEATLES SONGS, (in Alphabetical Order). P-84 7-REFERENCES and Conclusion. P-98 1 ==================================== 1-CHRONOLOGY TIMELINE OF, Events, Shows, Concerts, Albums & Songs Recorded and Release dates. ==================================== 1926-01-03- George Martin Producer of the Beatles was Born. George Martin died in his sleep on the night of 8 March 2016 at his home inWiltshire, England, at the age of 90. ==================================================================== 1934-09-19- Brian Epstein, The Beatles' manager, was born on Rodney Street, in Liverpool. Epstein died of an overdose of Carbitral, a form of barbiturate or sleeping pill, in his locked bedroom, on 27 August 1967. ==================================================================== 1940-07-07- Richard Starkey was born in family home, 9 Madyrn Street, Dingle, in Liverpool, known as Ringo Starr Drummer of the Beatles. Maried his first wife Maureen Cox in 1965 Starr proposed marriage at the Ad-Lib Club in London, on 20 January 1965. They married at the Caxton Hall Register Office, London, in 1965, and divorced in 1975. Starr met actress Barbara Bach, they were married on 27 April 1981. 1940-10-09- JohnWinston Lennon was born to Julia and Fred Lennon at Oxford Maternity Hospital in Liverpool., known as John Lennon of the Beatles. Lennon and Cynthia Powell (1939– 2015) met in 1957 as fellow students at the Liverpool College of Art. The couple were married on 23 August 1962. Their divorce was settled out of court in November 1968. -

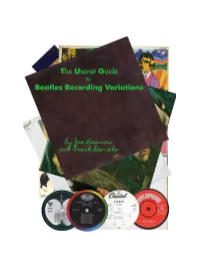

Beatles Recording Variations

The Usenet Guide to Beatles Recording Variations by Joseph Brennan: [email protected] 435 South Ridgewood Road, South Orange NJ 07079 Current version revised by Frank Daniels: [email protected] www.friktech.com/btls/btls2.htm © 1993,1994,1995,1996,1997,1998,1999,2000,2002 Joseph Brennan Portions © 2010, 2014 by Frank Daniels; version 3 © 2014, 2019, 2021 by Joseph Brennan & Frank Daniels. Introduction • What is Usenet? • Introduction: What's a Variation, and Why Do We Care? • Frank’s Intro • Credits • Notes on US Record Releases • Notes on CD Releases • The Films and the Videos • Format of entries Variations and Conclusions • 1958 to 1961 (including recordings with Tony Sheridan) • 1962 • 1963 (Please Please Me, With the Beatles) • 1964 (A Hard Day's Night, Beatles for Sale) • 1965 (Help!, Rubber Soul) • 1966 (Revolver) • 1967 (Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Magical Mystery Tour & Yellow Submarine) • 1968 (The Beatles and Yellow Submarine) • 1969 and 1970 (Abbey Road, Let It Be) • 1994 and 1995 (Anthology) • The Yellow Submarine Songtrack (1999) • British and German Discographies • Love (2006) and The Mono and Stereo Remasters (2009) • Song Index While researching recording variations, we ended up making lists of the Beatles original vinyl releases in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany. Please see Frank Daniels's Across the Universe pages on worldwide releases. The releases of the Beatles' Hamburg Recordings (from 1961 and 1962) are so confusing that there is a special introduction to those eight songs in the Guide. For links and stuff, please go see The Internet Beatles Album. What is Usenet? Usenet is a worldwide Internet, threaded discussion system that operates via news servers all around the world. -

THE BEATLES IMAGE: MASS MARKETING 1960S BRITISH and AMERICAN MUSIC and CULTURE, OR BEING a SHORT THESIS on the DUBIOUS PACKAGE of the BEATLES

THE BEATLES IMAGE: MASS MARKETING 1960s BRITISH AND AMERICAN MUSIC AND CULTURE, OR BEING A SHORT THESIS ON THE DUBIOUS PACKAGE OF THE BEATLES by Richard D Driver, Bachelor of Arts A Thesis In HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Aliza S Wong Randy McBee John Borrelli Dean of the Graduate School May, 2007 Copyright 2007, Richard Driver Texas Tech University, Richard D Driver, May 2007 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work could not have been possible without the encouragement and guidance of a number of individuals, as well as countless persons who pulled books, worked through interlibrary loans, and simply listened to me talk about it. Without the guidance, tolerance, insight, time, and encouragement of my committee, Aliza S Wong and Randy McBee, this thesis would have remained nothing more than a passing thought. Aliza, more than any other professor has been there for me since this project truly began over two years ago. It was her initial push for me to write about something I loved that drove me to attend Graduate school and then build upon what I had done previously with The Beatles “image.” Dr. McBee provided excellent guidance into understanding many of the post-war American facets of this work, not simply those related to The Beatles or music in general. Additional thanks are reserved for Dr. Julie Willett for her class on sexuality and gender where new methods and modes of historical thought were founded in this work. Finally, this thesis would have been impossible had I not been accepted into and granted a teaching position in the History Department at Texas Tech University, and it is to the entire department that I owe my greatest thanks. -

The Walrus Was Paul!

NOTES ON A STRANGE WORLD MASSIMO POLIDORO The Walrus Was Paul! id you know that Paul McCartney, the ex-Beatle, Dnever actually left the band because . he died in 1966 and was then replaced by a lookalike? It sounds bizarre, and it is. The “Paul is dead” myth is one of the most popular myths set in the world of rock music and per- haps the most fun to follow up. It all began on October 12, 1969, when Russ Gibb, a DJ for Detroit’s underground station WKNR-FM, re- ceived a phone call by a man named “Tom,” who claimed that some Beatles records contained hidden clues suggesting that Paul McCartney had actually died. The evidence for a conspiracy revolved around the theory that Paul had been decapitated in an automobile wreck after he left Abbey Road studios in London, where the Beatles recorded their music. Paul had apparently left upset over an argument with the other Beatles, took his Aston Martin sportscar, and perished in a horrible accident that killed him. This accident supposedly took place at 5 A.M. on November 9, 1966, and John Lennon and Paul McCartney are shown on their arrival at Palam airport, near Delhi, India, on their way was caused by a hitchhiker named Rita to meet with their guru, The Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Photo by UPPA/ZUMA Press. Copyright 1966 by UPPA [Photo via NewsCom] who Paul had picked up along the road. With Paul’s death, however, a big somebody who looked like him and songs as McCartney and just happened problem arose: the Beatles were at the could play music. -

Remembering George 2016

1 Playlist Nov. 27th 2016 Remembering George 9AM The Beatles - Blue Jay Way - Magical Mystery Tour (EP) (Harrison) Lead vocal: George Written by George Harrison on August 1, 1967 while vacationing in a rented house in the Hollywood Hills above Los Angeles. The story is essentially the same as the lyrics imply. On a foggy night in L.A., George sat at his rented house waiting for friends to arrive, but the maze of thin and winding streets and the thick fog rolling in got the best of them and they became lost. George: “I’d rented a house in Los Angeles on – Blue Jay 2 Way, and I’d arrived there from England. I was waiting around for Derek and Joan Taylor who were then living in L.A. I was very tired after the flight and the time change and I stared writing, playing a little electric organ that was in the house. It had gotten foggy and they couldn’t find the house for some time. The mood is slightly Indian.” Following the release of the song on the “Magical Mystery Tour” LP in America, the City of Los Angeles got so tired of having to replace stolen “Blue Jay Way” street signs that it had the street name painted on walls along the street’s route. The backing track was recorded in one take on September 6, 1967. On U.S. album: Magical Mystery Tour - Capitol LP The Beatles - Long Long Long - The Beatles (Harrison) Lead vocal: George George, Paul and Ringo ran through 67 takes of George’s “Long Long Long,” then titled “It’s Been A Long Long Long Time,” on October 7, 1968.