Glimpses Into the Historic Importance of the Inland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics Lake Michigan is a dynamic deepwater oligotrophic ecosystem that supports a diverse mix of native and non-native species. Although the watershed, wetlands, and tributaries that drain into the open waters are comprised of a wide variety of habitat types critical to supporting its diverse biological community this section will focus on the open water component of this system. Watershed, wetland, and tributaries issues will be addressed in the Northeastern Morainal Natural Division section. Species diversity, as well as their abundance and distribution, are influenced by a combination of biotic and abiotic factors that define a variety of open water habitat types. Key abiotic factors are depth, temperature, currents, and substrate. Biotic activities, such as increased water clarity associated with zebra mussel filtering activity, also are critical components. Nearshore areas support a diverse fish fauna in which yellow perch, rockbass and smallmouth bass are the more commonly found species in Illinois waters. Largemouth bass, rockbass, and yellow perch are commonly found within boat harbors. A predator-prey complex consisting of five salmonid species and primarily alewives populate the pelagic zone while bloater chubs, sculpin species, and burbot populate the deepwater benthic zone. Challenges Invasive species, substrate loss, and changes in current flow patterns are factors that affect open water habitat. Construction of revetments, groins, and landfills has significantly altered the Illinois shoreline resulting in an immeasurable loss of spawning and nursery habitat. Sea lampreys and alewives were significant factors leading to the demise of lake trout and other native species by the early 1960s. -

Mason's Minnesota Statutes 1927

1940 Supplement To Mason's Minnesota Statutes 1927 (1927 to 1940) (Superseding Mason s 1931, 1934, 1936 and 1938 Supplements) Containing the text of the acts of the 1929, 1931, 1933, 1935, 1937 and 1939 General Sessions, and the 1933-34,1935-36, 1936 and 1937 Special Sessions of the Legislature, both new and amendatory, and notes showing repeals, together with annotations from the various courts, state and federal, and the opinions of the Attorney General, construing the constitution, statutes, charters and court rules of Minnesota together with digest of all common law decisions. Edited by William H. Mason Assisted by The Publisher's Editorial Staff MASON PUBLISHING CO. SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA 1940 CH. 56C—NEWSPAPERS §7392 7352-14. Violation a gross misdemeanor.—In the with the ownership, printing or publishing of any such event of any newspaper failing to file and register as publication or of any article published therein either provided for in Section 1 of this act, the party printing in a criminal action for libel by reason of such publica- or publishing the same shall be guilty of a gross mis- tion or in any civil action based thereon. (Act Apr. demeanor. (Act Apr. 21, 1931, c. 293, §4.) 21, 1931, c. 293, §5.) 7352-15. Court to determine ownership.—In the 7353-10. Definition.—By the term "newspaper" aa event of the publication of any newspaper within the expressed herein, shall be included any newspaper, State of Minnesota without the names of-the owners circular or any other publication whether issued regu- and publishers thereof fully set forth in said news- larly or intermittently by the same parties or by paper, circular or publication, the court or the jury may determine such ownership and publisher on evi- parties, one of whom has been associated with one or dence of the general or local reputation of that fact more publication of such newspaper or circular, and opinion evidence may be offered and considered whether the name of the publication be the same or by the court or Jury in any case arising in connection different. -

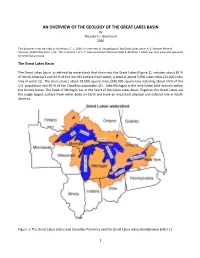

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

Indiana Michigan Power Company State of Indiana

I.U.R.C. NO. 18 ORIGINAL SHEET NO. 1 INDIANA MICHIGAN POWER COMPANY STATE OF INDIANA INDIANA MICHIGAN POWER COMPANY SCHEDULE OF TARIFFS AND TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SERVICE GOVERNING SALE OF ELECTRICITY IN THE STATE OF INDIANA ISSUED BY EFFECTIVE FOR ELECTRIC SERVICE RENDERED TOBY L. THOMAS ON AND AFTER MARCH 11, 2020 PRESIDENT FORT WAYNE, INDIANA ISSUED UNDER AUTHORITY OF THE INDIANA UTILITY REGULATORY COMMISSION DATED MARCH 11, 2020 IN CAUSE NO. 45235 I.U.R.C. NO. 18 ORIGINAL SHEET NO. 2 INDIANA MICHIGAN POWER COMPANY STATE OF INDIANA LOCALITIES WHERE ELECTRIC SERVICE IS AVAILABLE LOCALITY COUNTY LOCALITY COUNTY Aboite Township Allen Decatur Adams Adams Township Allen Delaware Township Delaware Albany Randolph Dunkirk Jay Albion Noble Blackford Albion Township Noble Duck Creek Township Madison Alexandria Madison Allen Township Noble Eaton Delaware Anderson Township LaPorte Eel River Township Allen Elkhart Elkhart Baugo Township Elkhart Elwood Madison Bear Creek Township Jay Bear Creek Township Adams Fall Creek Township Henry Benton Township Elkhart Fairfield Township DeKalb Berne Adams Fairmount Grant Blountsville Henry Farmland Randolph Blue Creek Township Adams Fort Wayne Allen Boone Township Madison Fowlerton Grant Bryant Jay Franklin Township DeKalb Bryant Township Wells Franklin Township Grant Butler DeKalb Franklin Township Randolph Butler Township DeKalb French Township Adams Cedar Creek Township Allen Galena Township LaPorte Center Township Delaware Gas City Grant Center Township Grant Gaston Delaware Center Township LaPorte Geneva Adams Center Township Marshall German Township St. Joseph Centre Township St. Joseph Grabill Allen Chester Township Wells Grant Township DeKalb Chesterfield Madison Green Township Noble Churubusco Whitley Green Township Randolph Clay Township St. -

10 Cal.2D 677, 15646, Hillside Water Co. V. Los Angeles /**/ Div.C1

10 Cal.2d 677, 15646, Hillside Water Co. v. Los Angeles /**/ div.c1 {text-align: center} /**/ Page 677 10 Cal.2d 677 76 P.2d 681 HILLSIDE WATER COMPANY (a Corporation), Respondent, v. CITY OF LOS ANGELES (a Municipal Corporation) et al., Appellants, TOWN OF BISHOP (a Municipal Corporation) et al., Interveners and Respondents. L. A. No. 15646. Supreme Court of California February 16, 1938 In Bank. Page 678 [Copyrighted Material Omitted] Page 679 COUNSEL Ray L. Chesebro, City Attorney, James M. Stevens and S. B. Robinson, Assistant City Attorneys, Carl A. Davis, Deputy City Attorney, and T. B. Cosgrove for Appellants. Thomas C. Boone, Glenn E. Tinder, Preston & Braucht, John W. Preston and Preston & Preston for Respondents. OPINION SHENK, J. On May 9, 1931, the plaintiff Hillside Water Company, a corporation, filed a complaint in the Superior Court in and for the County of Inyo, seeking to enjoin the defendants, City of Los Angeles, and its Board of Water and Power Commissioners from "flowing, pumping, or otherwise exporting any of the waters" from any of the defendants' water wells located on the defendants' lands overlying the underground basin known as the Bishop-Big Pine Basin in Inyo County, and from diverting and transporting any of the waters from said basin to any place or land not overlying said basin. The Bishop-Big Pine Basin comprises an area of about 95,000 acres. It is located in [76 P.2d 683] the Owens River water shed and is bounded (approximately) on the north by the northerly boundary of Inyo County, on the east by the Inyo Mountains, on the south by Tinnemaha dam, which is about seven miles south of the town of Big Pine, and on the west by the Sierra Nevada, a mountain range. -

Burt Lake Shoreline Survey 2009

Burt Lake Shoreline Survey 2009 By Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council Report written by: Kevin L. Cronk Monitoring and Research Coordinator Table of Contents Page List of Tables and Figures iii Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 2 Shoreline development impacts 3 Study Area 7 Methods 13 Field Survey Parameters 13 Data processing 17 Results 18 Discussion 21 Recommendations 26 Literature and Data Referenced 29 ii List of Tables Page Table 1. Burt Lake watershed land-cover statistics 9 Table 2. Categorization system for Cladophora density 15 Table 3. Cladophora density statistics 18 Table 4. Septic Leachate Detector (SLD) results 18 Table 5. Greenbelt score statistics 19 Table 6. Shoreline alteration statistics 19 Table 7. Cladophora density comparisons: 2001 to 2009 21 Table 8. Greenbelt rating comparisons: 2001 to 2009 21 Table 9. Shore survey statistics from Northern Michigan lakes 22 List of Figures Page Figure 1. Map of Burt Lake, Features and Depths 8 Figure 2. Map of the Burt Lake watershed 10 Figure 3. Chart of phosphorus data from Burt Lake 12 Figure 4. Chart of trophic status index data from Burt Lake 12 iii SUMMARY During the summer of 2009, the Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council conducted a comprehensive shoreline survey on Burt Lake that was sponsored by the Burt Lake Preservation Association. Watershed Council staff surveyed the entire shoreline in June and July to document conditions that potentially impact water quality. The parameters surveyed include: algae as a bio-indicator of nutrient pollution, greenbelt status, shoreline erosion, shoreline alterations, nearshore substrate types, and stream inlets and outlets. -

Cheboygan County Local Ordinance Gaps Analysis

Cheboygan County Local Ordinance Gaps Analysis An essential guide for water protection Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council Written and compiled by Grenetta Thomassey, Ph.D. Cheboygan County Local Ordinance Gaps Analysis An essential guide for water protection Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council Written and compiled by Grenetta Thomassey, Ph.D. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. Mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities in this book do not imply endorsement by the author or publisher, nor does the mention of specific companies, organizations or authorities imply that they endorse this book, its author or publisher. Internet addresses and phone numbers given in this book were accurate at the time of printing. Library of Congress Catalog Thomassey, Grenetta Cheboygan County Local Ordinance Gaps Analysis ISBN 978-1-889313-07-8 1. Government 2. Water Protection 3. Cheboygan County, Michigan © 2014 Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Photography by: Kristy Beyer If you want to reproduce this book or portions of it for reasons consistent with its purpose, please contact the publisher: Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council 426 Bay Street Petoskey, MI 49770 (231) 347-1181 phone (231) 347-5928 fax www.watershedcouncil.org This work should be cited as follows: Thomassey, Grenetta. Cheboygan County Local Ordinance Gaps Analysis 2014. Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council, Petoskey, MI 49770 ~ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

Fact Sheet with Links to Key Information Can Be Accessed Online Here

Now is the time of reckoning for the decaying Enbridge Line 5 oil pipelines in the Straits of Mackinac and a proposed oil tunnel to replace them. On June 27, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel took decisive legal action on Line 5 in the Straits of Mackinac when she filed suit in Ingham County Circuit Court to revoke the 1953 easement that conditionally authorized Enbridge to pump oil through twin pipelines. Nessel’s lawsuit alleges that Enbridge’s continued operation of the Straits Pipelines violates the Public Trust Doctrine, is a common law public nuisance, and violates the Michigan Environmental Protection Act based on potential pollution, impairment, and destruction of water and other natural resources. Simultaneously, Governor Gretchen Whitmer and the natural resources and environmental protection agencies are defending the public’s rights and waters of the Great Lakes in Enbridge’s separate lawsuit against the state to build a tunnel under the Great Lakes for its oil pipelines to operate another 99 years. Gov. Whitmer also ordered the Michigan Department of Natural Resources to review violations of the Line 5 easement. As the state’s top leader and public trustee, the governor has the express legal authority to revoke the easement to start decommissioning the pipeline and to protect the Great Lakes. On June 6, Canada’s Line 5-owner Enbridge sued the State of Michigan to resuscitate a ‘Line 5’ oil tunnel deal and law rushed through in late 2018 at the end of the Snyder administration. Attorney General Dana Nessel in late March declared the oil tunnel law unconstitutional, triggering Gov. -

Burt Lake Watershed Permit Guide

Attention All Burt Lake Watershed Property Owners: If you have plans to build, drill or fill there are some things you should know before you begin. Many home improvement activities are regulated by local, state or federal agencies. As a result, a review process and permits are often required before work begins. This process can be confusing for the homeowner seeking answers. To help you navigate through the right channels, we offer this resource to set you on your course toward achieving your property goals. If any of the following activities are included in your future plans for your property in Cheboygan or Emmet County, learn now what steps you will need to take. As a Northern Michigan resident, you are surrounded by our beautiful natural resources every day. Preserving Regulated activities on private the character and quality of the land and water is very likely important to you. Regulations are intended property include: to protect water resources, as well as neighboring • Building a new home properties. Activities inconsistent with permitted uses threaten the immediate and future health of these • Modifying an existing home (expanding resources. By observing standards established in local or building an addition) ordinances, you can do your part to protect the waters • Installing a new septic system of Burt Lake and the Burt Lake Watershed. • Repairing an existing septic system A healthy watershed depends on sound and responsible • Excavating earth within 500 feet of a lake or land use. The presence of pollutants anywhere within stream or if an earth change will disturb an acre the Watershed can easily end up in Burt Lake and its or more of land (regardless of distance to lake connecting waters. -

Exploring Historical Literacy in Manitoulin Island Ojibwe

Exploring Historical Literacy in Manitoulin Island Ojibwe ALAN CORBIERE Kinoomaadoog Cultural and Historical Research M'Chigeeng First Nation This paper will outline uses of Ojibwe1 literacy by the Manitoulin Island Nishnaabeg2 in the period from 1823 to 1910. Most academic articles on the historical use of written Ojibwe indicate that Ojibwe literacy was usu ally restricted to missionaries and was used largely in the production of religious materials for Christianizing Native people. However, the exam ples provided in this paper will demonstrate that the Nishnaabeg of Mani toulin Island3 had incorporated Ojibwe literacy not only in their religious correspondence but also in their personal and political correspondence. Indeed, Ojibwe literacy served multiple uses and had a varied audience and authorship. The majority of materials written in Ojibwe over the course of the 19th century was undoubtedly produced by non-Native people, usually missionaries and linguists (Nichols 1988, Pentland 1996). However, there are enough Nishnaabe-authored Ojibwe documents housed in various archives to demonstrate that there was a burgeoning Nishnaabe literacy movement from 1823 to 1910. Ojibwe documents written by Nishnaabe chiefs, their secretaries, and by educated Nishnaabeg are kept at the fol lowing archives: the United Chief and Councils of Manitoulin's Archives, the National Archives of Canada, the Jesuit Archives of Upper Canada and the Archives of Ontario. 1. In this paper I will use the term Ojibwe when referring to the language spoken by the Nishnaabeg of Manitoulin. Manitoulin Nishnaabeg include the Ojibwe, Potawatomi and Odawa nations. The samples of "Ojibwe writing" could justifiably be called "Odawa writ- ing. -

Michigan Statewide Historic Preservation Plan

2020–2025 MICHIGAN Statewide Historic Preservation Plan Working together, we can use the next five years to redefine the role of historic preservation in the state to ensure it remains relevant to Michigan’s future. State Historic Preservation Office Prepared by 300 North Washington Square Amy L. Arnold, Preservation Planner, Lansing, Michigan 48913 Michigan State Historic Preservation Office, Martha MacFarlane-Faes, Lansing, Michigan Deputy State Historic August 2020 Preservation Officer Mark Burton, CEO, With assistance from Michigan Economic Peter Dams, Dams & Associates, Development Corporation Plainwell, Michigan Gretchen Whitmer, Governor, This report has been financed entirely State of Michigan with federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. This program receives federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or you desire further information, please write to: Office for Equal Opportunity National Park Service 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington D.C. 20240 Cover photo: Thunder Bay Island Lighthouse, Alpena County. Photo: Bryan Lijewski Michigan State Historic Preservation Office 2 Preservation Plan 2020–2025 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... -

2019 Parks and Recreation Guide

EMMET COUNTY PARKS & RECREATION Headlands International Dark Sky Park Camp Petosega ▪ Fairgrounds ▪ McGulpin Lighthouse Crooked River Locks ▪ Bike Trails ▪ Cecil Bay emmetcounty.org/parks-recreation 231-348-5479 | [email protected] 21546_ParksandRecGuide.indd 1 3/4/19 8:17 AM Welcome to Emmet County, Michigan Welcome to our Parks and Recreation Guide! In these pages, we’re going to give you a snapshot tour of Emmet County’s most special amenities, from our International Dark Sky Park at the Headlands to our vast, connected trail network, to our parks and beaches, towns and natural resources. This is a special place, tucked into the top of Michigan’s mitten in the Northwest corner, a place where radiant sunsetsWhere and extraordinary fallquality color complement fluffyof lifeand abundant snowfall and the most satisfying shoreline summers you’ve ever spent. It’s a place that for centuries has been home to the is Odawa Indian tribe and the descendants of settlers from French and British beginnings.everything Here, the outdoors is yours to explore thanks to foresight and commitment from local officials who think one of the best things we can do for the public is to provide access to lakes, rivers, nature preserves, trails, parks and all the points in between. Here, there’s no shortage of scenery as you traverse our 460 square miles, from the tip of the Lower Peninsula at the Mackinac Bridge, to quaint little Good Hart on the west, the famed Inland Waterway at our east, and Petoskey and Bay Harbor to the south. We hope you enjoy your tour