The Road to 1944

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council Planning Search 22-03-2013

SOUTH EAST WALES BIODIVERSITY RECORDS CENTRE PLANNING SEARCH SERVICE Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council Planning Search 22-03-2013 Application Type Date Proposal Location Grid Agent/Applicant No. Reference 13/0023/10 Full 21/03/20 Single storey front extension and storage area 38 MISKIN ROAD, TREALAW, SS99718924 Ms N McCarthy 37 Miskin Road Trealaw [CPU] planning 13 underneath and patio area (re-submission). TONYPANDY, CF40 2QJ 89 Tonypandy CF40 2QJ permission SEWBReC Application Group 2 (250m) Number of European Protected Species Records 3 Distanc Taxon Common Name Grid Date Recorder(s) Coun Location Comments Source e (m) Referenc t e Chiroptera Unspecified Bat SS9992 2005 Lisa Palmer Holburn Terrace, Bat found in house . Ref: CCW (Cardiff) Bat Tonypandy, Rhondda 0624 - Call taken by Erica Casework File 2005 Colkett Pipistrellus Pipistrelle SS9992 12 Jul 2010 Hugh Dixon Riverview, Tonypandy, Ref 1244. Roost within CCW (Cardiff) Bat Rhondda extension. Droppings present. Casework File 2010 Owner has counted approx 20 emerging. Chiroptera Unspecified Bat SS9992 20 Nov Rachel Hughes Kenry Street, Rhondda Bats discovered in roof CCW (Cardiff) Bat 2002 space. Ref: 0092. Casework File 2002 Number of records of Wildlife & Countryside Act species 5 Distanc Taxon Common Name Grid Date Recorder(s) Coun Location Comments Source e (m) Reference t 01740* Tyto alba Barn Owl ST00024942 23 Aug Richard Poole Llwynypia Observed circling low overhead SEWBReC Casual 02 2010 Hospital (height approx 30 ft) before leaving Records (Derelict) hospital site -

The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: an Anglican Perspective on State Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education George Sochan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sochan, George, "The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education" (1995). Dissertations. 3521. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 George Sochan LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CULTURAL ROLE OF CHRISTIANITY IN ENGLAND, 1918-1931: AN ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON STATE EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY GEORGE SOCHAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1995 Copyright by George Sochan Sochan, 1995 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • ••.••••••••••.•••••••..•••..•••.••.•• 1 II. THE CALL FOR REFORM AND THE ANGLICAN RESPONSE ••.• 8 III. THE FISHER ACT •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 35 IV. NO AGREEMENT: THE FAILURE OF THE AMENDING BILL •. 62 v. THE EDUCATIONAL LULL, 1924-1926 •••••••••••••••• 105 VI. THE HADOW REPORT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 135 VII. THREE FAILED BILLS, THEN THE DEPRESSION •••••••• 168 VIII. CONCLUSION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 218 BIBLIOGRAPHY •••••••••.••••••••••.••.•••••••••••••••••.• 228 VITA ...........................................•....... 231 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since World War II, beginning especially in the 1960s, considerable work has been done on the history of the school system in England. -

Poverty and Philanthropy in the East

KATHARINE MARIE BRADLEY POVERTY AND PHILANTHROPY IN EAST LONDON 1918 – 1959: THE UNIVERSITY SETTLEMENTS AND THE URBAN WORKING CLASSES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD IN HISTORY CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between the university settlements and the East London communities through an analysis their key areas of work during the period: healthcare, youth work, juvenile courts, adult education and the arts. The university settlements, which brought young graduates to live and work in impoverished areas, had a fundamental influence of the development of the welfare state. This occurred through their alumni going on to enter the Civil Service and politics, and through the settlements’ ability to powerfully convey the practical experience of voluntary work in the East End to policy makers. The period 1918 – 1959 marks a significant phase in this relationship, with the economic depression, the Second World War and formative welfare state having a significant impact upon the settlements and the communities around them. This thesis draws together the history of these charities with an exploration of the complex networking relationships between local and national politicians, philanthropists, social researchers and the voluntary sector in the period. This thesis argues that work on the ground, an influential dissemination network and the settlements’ experience of both enabled them to influence the formation of national social policy in the period. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020 Christmas Christmas Service Days of Sunday Monday Boxing Day Friday Saturday Sunday Monday New Year's Eve New Year's Day Thursday Operators Route Eve Day number Operation 22 / 12 / 19 23 / 12 / 19 26 / 12 / 19 27 / 12 / 19 28 / 12 / 19 29 / 12 / 19 30 / 12 / 19 31 / 12 / 19 01 / 01 / 20 02 / 01 / 20 24 / 12 / 19 25 / 12 / 19 School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 1 Aberdare - Abernant No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 2 Aberdare - Tŷ Fry No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Early Finish Globe Mon to Sat Penrhiwceiber - Cefn Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 3 No Service No Service No Service No Service (see No Service Coaches (Daytime) Pennar Service Service Service Service Service Service summary) School School School Mon to Sat Aberdare - Llwydcoed - Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 6 No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Merthyr Tydfil Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Harris Mon to Sat Normal Normal Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Normal 7 Pontypridd - Blackwood No Service No Service No Service No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Service Service Service -

A Critical Analysis of the Concept of Christian Education with Particular Reference to Educational Discussion After 1957

Hughes, Frederick E. (1988) A critical analysis of the concept of Christian education with particular reference to educational discussion after 1957. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/13721/1/383536.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. · Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. · To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in Nottingham ePrints has been checked for eligibility before being made available. · Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not- for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. · Quotations or similar reproductions must be sufficiently acknowledged. Please see our full end user licence at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact [email protected] A critical analysis of the concept of Christian Education with particular reference to educational discussions after 1957 by Frederick E. -

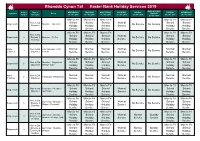

Rhondda Cynon Taf Easter Bank Holiday Services 2019

Rhondda Cynon Taf Easter Bank Holiday Services 2019 BANK HOLIDAY Service Days of WEDNESDAY THURSDAY GOOD FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY Operators Route MONDAY number Operation 17 / 04 / 2019 18 / 04 / 2019 19 / 04 / 2019 20 / 04 / 2019 21 / 04 / 2019 23 / 04 / 2019 24 / 04 / 2019 22 / 04 / 2019 Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 1 Aberdare - Abernant No Service No Service (Daytime) Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 2 (Daytime & Aberdare - Tŷ Fry No Service No Service Evening) Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Globe Mon to Sat Penrhiwceiber - Cefn Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 3 No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Pennar Service Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat Aberdare - Llwydcoed - School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 6 No Service No Service (Daytime) Merthyr Tydfil Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Harris Mon to Sat Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 7 Pontypridd - Blackwood No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat Penderyn - Aberdare - School -

Pakistanis, Irish, and the Shaping of Multiethnic West Yorkshire, 1845-1985

“Black” Strangers in the White Rose County: Pakistanis, Irish, and the Shaping of Multiethnic West Yorkshire, 1845-1985 An honors thesis for the Department of History Sarah Merritt Mass Tufts University, 2009 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Section One – The Macrocosm and Microcosm of Immigration 9 Section Two – The Dialogue Between “Race” and “Class” 28 Section Three – The Realization of Social and Cultural Difference 47 Section Four – “Multicultural Britain” in Action 69 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 99 ii Introduction Jess Bhamra – the protagonist in the 2002 film Bend It Like Beckham about a Hounslow- born, football-playing Punjabi Sikh girl – is ejected from an important match after shoving an opposing player on the pitch. When her coach, Joe, berates her for this action, Jess retorts with, “She called me a Paki, but I guess you wouldn’t understand what that feels like, would you?” After letting the weight of Jess’s frustration and anger sink in, Joe responds, “Jess, I’m Irish. Of course I understand what that feels like.” This exchange highlights the shared experiences of immigrants from Ireland and those from the Subcontinent in contemporary Britain. Bend It Like Beckham is not the only film to join explicitly these two ethnic groups in the British popular imagination. Two years later, Ken Loach’s Ae Fond Kiss confronted the harsh realities of the possibility of marriage between a man of Pakistani heritage and an Irish woman, using the importance of religion in both cases as a hindrance to their relationship. Ae Fond Kiss recognizes the centrality of Catholicism and Islam to both of these ethnic groups, and in turn how religion defined their identity in the eyes of the British community as a whole. -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Starting School 2018-19 Cover Final.Qxp Layout 1

Starting School 2018-2019 Contents Introduction 2 Information and advice - Contact details..............................................................................................2 Part 1 3 Primary and Secondary Education – General Admission Arrangements A. Choosing a School..........................................................................................................................3 B. Applying for a place ........................................................................................................................4 C.How places are allocated ................................................................................................................5 Part 2 7 Stages of Education Maintained Schools ............................................................................................................................7 Admission Timetable 2018 - 2019 Academic Year ............................................................................14 Admission Policies Voluntary Aided and Controlled (Church) Schools ................................................15 Special Educational Needs ................................................................................................................24 Part 3 26 Appeals Process ..............................................................................................................................26 Part 4 29 Provision of Home to School/College Transport Learner Travel Policy, Information and Arrangements ........................................................................29 -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Changes in the Provision of Physical Education for Children Under Twelve Years

Durham E-Theses Changes in the provision of physical education for children under twelve years. 1870-1992 Bell, Stephen Gordon How to cite: Bell, Stephen Gordon (1994) Changes in the provision of physical education for children under twelve years. 1870-1992, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5534/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CHANGES IN THE PROVISION OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION FOR CHILDREN UNDER TWELVE YEARS. 1870-1992 Stephen Gordon Bell The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis presented for the degree of M.A.(Ed,) in the Faculty of Social Science University of Durham 1994 I 0 JUM 199! Abstract A chronological survey over 120 years cannot fail to illustrate the concept of changesas history and change are inter-twined and in some ways synonymous„ Issues arising from political,social,financial,religious, gender and economic constraints affecting the practice and provision of Physical Education for all children under 12 in the state and independent sectors,including those with special needs,are explored within the period.The chapter divisions are broadly determined by the Education Acts of 1870,1902,1918,1944 and 1988 to illustrate developing changes.